Over our 22-year history, we’re proud to have published 22 articles by our esteemed colleague and friend William Ferris—from interviewing B.B. King to finding Faulkner in Bulgaria.

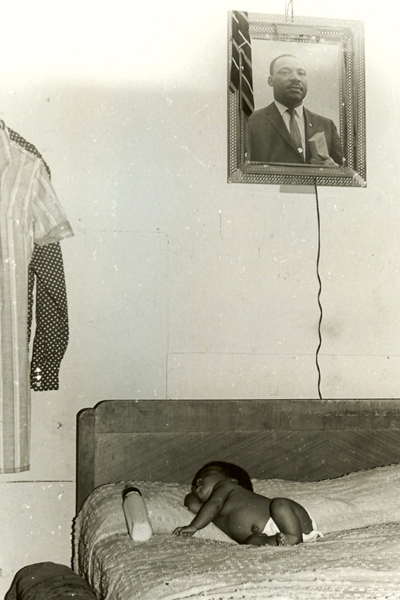

William Ferris is one of the greatest documentarians of the twentieth-century South. His collection of photographs, audio, film, and writings at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection encompasses some 173,000 pieces. Still, Ferris continues to record and snap photos, and regularly adds to its breadth.

Ferris’s depth of knowledge and intimacy with the region’s most famous cultural figures makes his writing for Southern Cultures among the journal’s richest content. As we launch the new Southern Cultures website, we thought it would be fitting to offer a Ferris Finder for the twenty-two essays he has published in the twenty-two years since the journal was founded.

In honor of Ferris’s contributions to the journal, we offer highlights from his interviews with Eudora Welty and B.B. King, including audio and photographs from the William R. Ferris Collection at UNC.

As a child I went to a little rural Black church on the [family] farm where I learned the hymns and as I grew older, I realized that when those families were gone the hymns would disappear. I began to record and photograph those worlds.

William Ferris, 2016

“Everything leads me back to the feeling of the blues.”

B.B. King, 1974

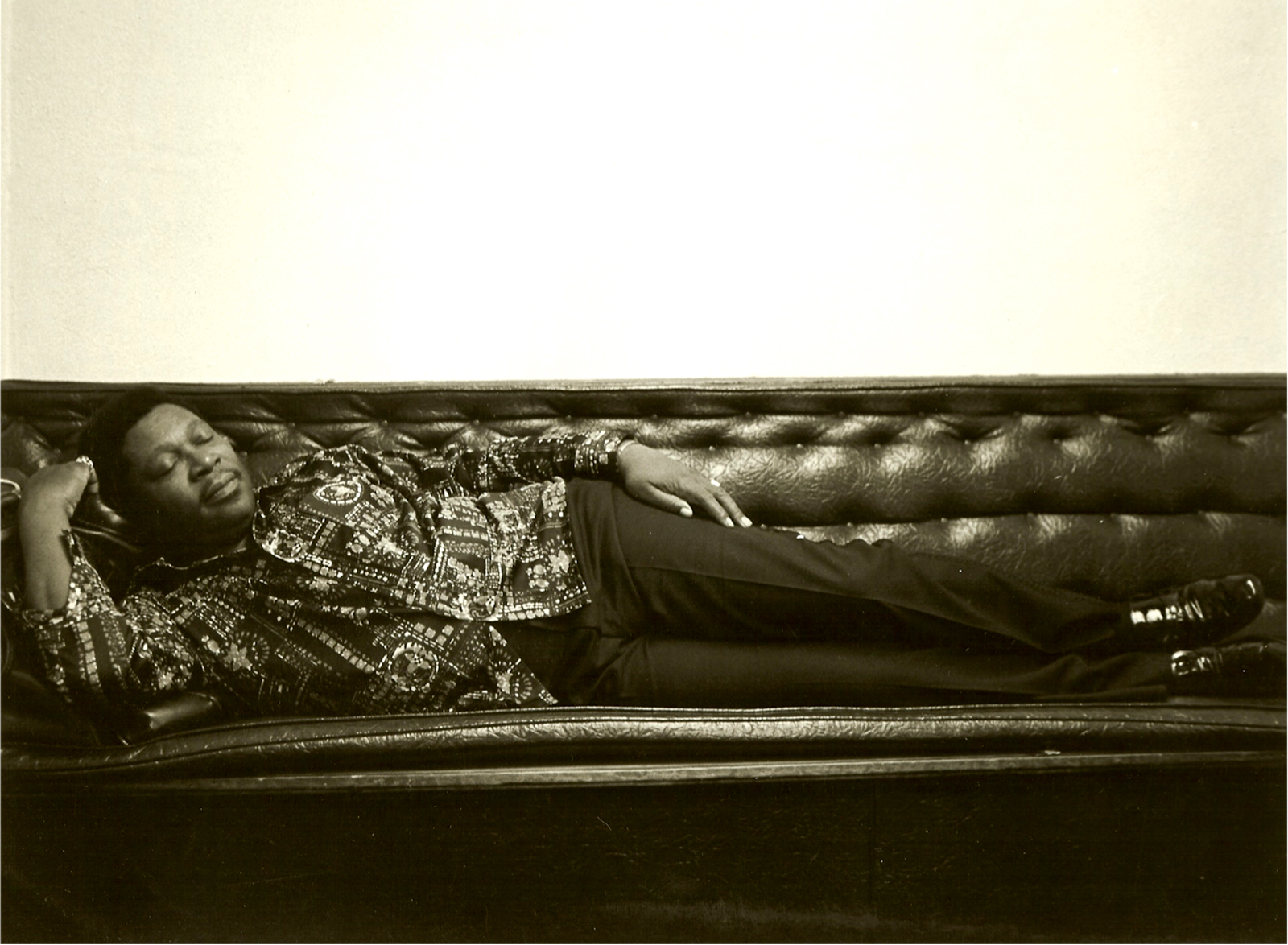

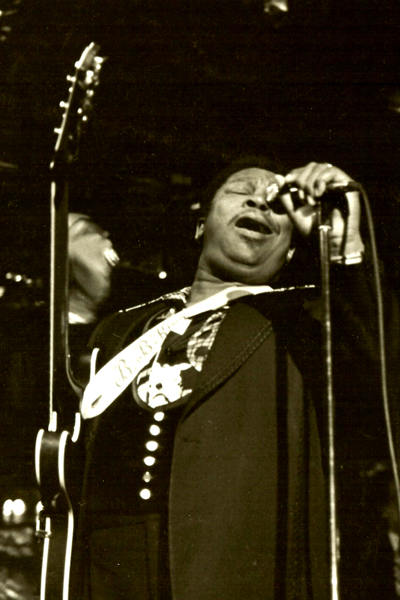

B.B. King’s name is synonymous with the blues. At the age of eighty-one, the blues patriarch maintains a rigorous schedule of performances throughout the nation and overseas that would exhaust a much younger artist. King’s performances and recordings have shaped the blues for more than six decades, reaching out to each new generation in terms they understand and embrace.

As an artist, B.B. King defies definition. Born Riley B. King on a plantation in the Mississippi Delta near the towns of Itta Bena and Indianola, he was profoundly shaped by gospel singers in the Black church, as well as by blues artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson. In he hitched a ride to Memphis, where he lived for ten months with his mother’s cousin Bukka White, a noted blues artist. In Memphis, King launched his career as the “Pepticon Boy,” advertising Pepticon medicine on radio station L9>6 and also performing with Bobby Bland, Johnny Ace, and Earl Forest in a group called “The Beale Streeters.” King adopted the nickname “The Beale Street Blues Boy,” which he shortened to “Blues Boy,” and then to “B.B.”

In 1950 King’s “Three O’Clock Blues” topped the rhythm-and-blues charts for four months and launched his career as a professional musician. He organized his own band and went on the road, barely two years since he made his last cotton crop in the Delta. Thus began a career that has continued uninterrupted to the present and underscores the power of his line, “Night life is a good life, the only life I know.”

For twenty years King played over three hundred one-night stands a year in Black-owned clubs known as the “Chitlin’ Circuit.” He also played week-long engagements each year in large, urban Black theaters such as the Howard in Washington, the Regal in Chicago, and the Apollo in New York.

Read more of Ferris’s introduction to his 1974 interview with B.B. King in Southern Cultures, Vol. 12, No. 4: Music 2006.

The earliest sound of the blues that I can remember was in the fields, where people would be picking or chopping cotton. Usually, one guy would be plowing by himself or take his hoe and chop way out in front of everybody else. You would hear this guy sing most of the time—just a thing that would kind of begin, no special lyrics, just what he felt at the time.

B.B. King. New York, 1974

Eudora Welty: “. . . standing under a shower of blessings”

In the Fall 2003 issue of Southern Cultures, William Ferris published a previously unreleased interview with Eudora Welty at her home in Jackson, Mississippi, on March 3, 1996. Welty discusses her writing life and friendships, and in this excerpt, film and photography.

WF: Eudora, were films important to you? Did you enjoy going to them?

EW: Oh, yes. I always loved films because you could go to them in Jackson when you were a child, movies of a certain kind. I always loved the film. Didn’t you?

WF: I did, and do.

EW: It spoke to me, too. It spoke to me through the imagination. It was something you could do without any money to amount to anything. Now you have to pay untold money for a seat. But in those days, in Jackson, you could go for a quarter or something like that. I was lucky in every way, I think, growing up in Jackson. Life here was so easy, and for a quarter you could go to the movies and see a cat man named Dr. Caligari [The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a 1919 silent film by Robert Wiene].

Life was easy and simple. You walked where you went. I guess you look back on something through rose-colored glasses, but I know life was made easy for me and for my imagination. And also it just scared me to imagine whatever came next. Anyway, when I went to New York and Columbia, I did the same things. I went to the theater and the movies and read good books, of course. Like you, I had books in my family home that I could read, was encouraged to read.

WF: How did you first discover the camera and photography? Was that something you did as a child?

EW: Yes. My father was a photographer. He had nice cameras. I began to use a camera, too, and to develop film in the kitchen at night. The times were conducive too. You know, the WPA [Works Progress Administration] came along and everything was in such poverty here. It was there to be photographed. Anybody could have seen it. Even I, as a child, could recognize it. It was telling its own story in human terms. I don’t know what my father would have thought of my photographs because what he wanted was accuracy, and the actual picture taking—that was fine, that was part of it.

Read more of William Ferris’s interview with Eudora Welty in Southern Cultures, Vol. 9, No. 3: Fall 2003.

Any writer writes from within, but reading is what opens up that world. I’ve never felt any different, and I’m pretty old now. . . . I’m in my eighties. I better hurry up and learn some more quick.

Eudora Welty, 1996

Southern Cultures Ferris Finder

To read more of Ferris’s work from Southern Cultures, click on a title below.

1. Southern Literature and Folk Humor

Southern Cultures, Vol. 1, No. 4: Southern Humor

2. Eudora Welty: “. . . standing under a shower of blessings”

Southern Cultures, Vol. 9, No. 3: Fall 2003

3. Alice Walker: “I know what the earth says”

Southern Cultures, Vol. 10, No. 1: Spring 2004

4. John Dollard: Caste and Class Revisited

Southern Cultures, Vol. 10, No. 2: Summer 2004

5. Robert Penn Warren: “Mad for Poetry”

Southern Cultures, Vol. 10, No. 4: Winter 2004

6. Harold Burson on interviewing Faulkner

for the Memphis Commercial Appeal

Southern Cultures, Vol. 12, No. 1: Spring 2006

7. “Everything leads me back to the feeling of the blues.”

B.B. King, 1974

Southern Cultures, Vol. 12, No. 4: Music 2006

8. Walker Evans, 1974

Southern Cultures, Vol. 13, No. 2: Photography

9. Pete Seeger, San Francisco, 1989

(with Pete Seeger, Michael K. Honey)

Southern Cultures, Vol. 13, No. 3: Music 2007

10. Alan Lomax: The Long Journey

Southern Cultures, Vol. 13, No. 3: Music 2007

11. Alex Haley: Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1989:

Angels, Legends, and Grace

Southern Cultures, Vol. 14, No. 3: Civil Rights

12. The Devil and his Blues: James “Son Ford” Thomas

Southern Cultures, Vol. 15, No. 3: Music

13. Blues Greats

Southern Cultures, Vol. 15, No. 3: Music

14. “My Idol Was Langston Hughes”:

The Poet, the Renaissance, and Their Enduring Influence

with Margaret Alexander Walker

Southern Cultures, Vol. 16, No. 2: Southern Lives

15. Touching the Music: Charles Seeger

Southern Cultures, Vol. 16, No. 3: Roots Music

16. “A lengthening chain in the shape of memories”:

The Irish and Southern Culture

Southern Cultures, Vol. 17, No. 1: The Irish

17. “Those little color snapshots”: William Christenberry

Southern Cultures, Vol. 17, No. 2: Photography

18. Bobby Rush: “Blues Singer–Plus”

Southern Cultures, Vol. 17, No. 4: Music

19. Trading Verses: James “Son Ford” Thomas and Allen Ginsberg

Southern Cultures, Vol. 19, No. 1: Global Music

20. Moon Pies and Memories

(with Mildred Council, John Egerton, George Tindall,

Doug Marlette, and Lee Smith)

Southern Cultures, Vol. 19, No. 2: Summer 2013

21. Interview: Krastan Dyankov with Henrietta Tordorova

Southern Cultures, Vol. 21, No. 2: Summer 2015

22. B.B. King: September 16, 1925–May 14, 2015

Southern Cultures, Vol. 21, No. 3: Music

*23. Handiwork: A Postscript from The South in Color

Southern Cultures, Vol. 22, No. 4: Winter 2006

*This list has been updated to include Ferris’s subsequent contributions.

All photographs are courtesy of the William R. Ferris Collection in Wilson Library’s Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.