“Freedom of mobility, accessibility of housing for one night or many, and a safe and secure environment for the many ways young Black women needed to spend their days—that was the point.”

One late August night in 1943, Robbie Shields traveled up from Woodlawn in the South Side to Chicago’s northern suburb of Evanston for a special weeklong summer program at Northwestern University. A twenty-six-year-old youth choir director, Shields was there to represent her church, Woodlawn ame, at the eleventh annual Church and Choral Music Institute, where she would join other vocalists in the program’s courses and in the chorus. Well, only the courses. Prior to her arrival, the director of the summer program had advised Shields to stay out of the choir, since there were so many southerners at Northwestern, thus insinuating that Jim Crow conventions would apply.

Shields’s room in the Willard Hall dormitory had been reserved for her weeklong stay and had been paid for, but when Shields arrived to check in, the desk attendant seemed surprised. The attendant refused to recognize Shields’s name on the list. She eventually called the house director, “who after one glance at Miss Shields, informed her that a room had been reserved for her—but at the North Shore Community House, a rooming-place across town for Negro girls.” The Community House stood on a corner half a mile from Willard Hall. Later, when questioned by the Chicago Defender and confronted by representatives from the ame Church who had heard from Shields, Northwestern’s dormitory officials defended the decision to deny her lodging, speaking instead of doing Shields a “great service,” saying, “We know that Negroes prefer to live with members of their own race.” Northwestern’s officials perhaps did not see themselves as denying Shields entry to the dorm due to her color, at least not solely. The Great Migration had turned the “White City” into a “Black Metropolis,” with waves of Black southern migrants settling in, troubling the social and spatial codes of the city, and making new plans for themselves like every other denizen of the twentieth century—sometimes, with riotous results. Like the choral director who turned Shields away from the choir, and like many voices who defended segregated living in Chicago, especially in the wake of the 1919 race riots, these officials portrayed themselves as protectors of racial peace rather than staunch segregationists. Their lawyers, however, would be more blunt, arguing that the young woman was “inferior to other normal young American women and unfit to live and associate with them,” even for just a weeklong summer program.1

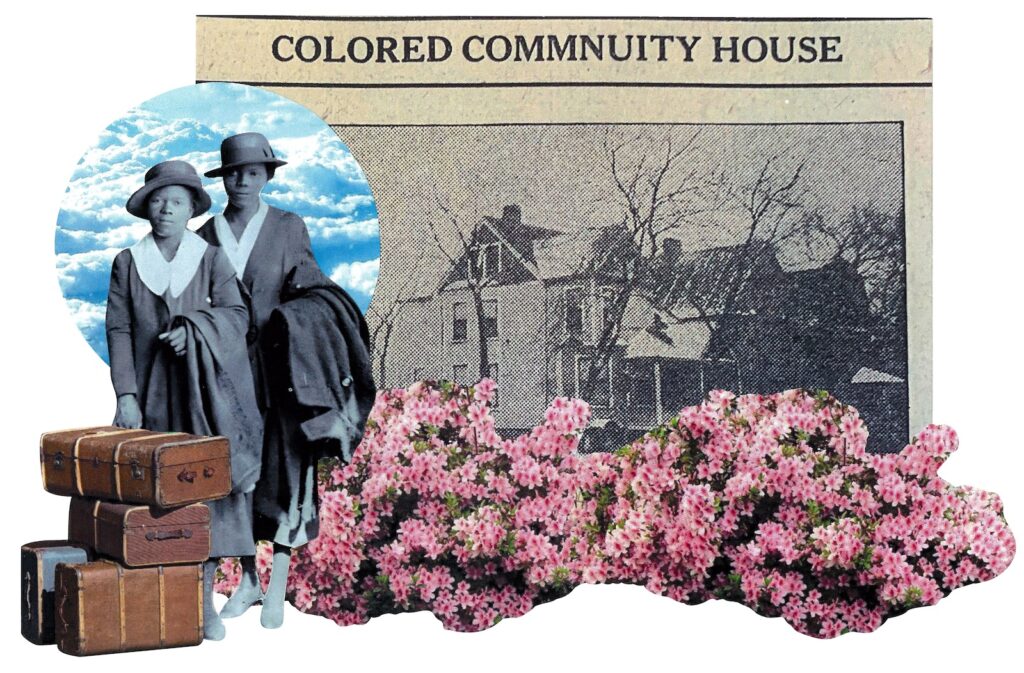

But before entering into the legal battle with Northwestern, one that she would eventually win, Shields needed a place to stay. In the middle of the night, she either walked or rode to the North Shore Community House at 1125 Garnett Place. The house stood on the corner between a residential street and a main road, at the top of a small hill, with tall trees lining the property and a mailbox and a fire hydrant at its apex. Operated by the Iroquois League, the local African American women’s club, the house was located on a street renamed in the 1920s in honor of one of Evanston’s first Black families. Shields arrived to find that a room had not been reserved for her at all. Ruth Birt, the house mother at North Shore, told her that the school had called “just 15 minutes ago,” rather short notice for an accommodation planned well in advance.2

The women and girls who lived in the North Shore Community House mostly worked as domestics for white people in private homes in Evanston. The house provided a bed and a safe “home away from home” on holidays, weekends, and other days off, when the workers were not permitted or did not want to be in their employers’ homes. The house was not, however, Northwestern’s backup dorm for young Black women. Ms. Birt and Shields likely shared each other’s frustration in that moment, recognizing yet another racially motivated inconvenience and wondering how they could have expected anything else.3

Shields was very likely not the first Black woman whom Northwestern had sent to the North Shore Community House for last-minute lodging. While the house could accommodate a dozen or so people, the need seemed to be greater, a situation that persisted from the time the house first opened its doors to residents in 1924 until its closing in the 1970s.

Reporting on the new “colored community house” for the Evanston News-Index in January 1925, R. E. Wilson wrote that the house had been planned, purchased, and furnished within “record time” after the need for the house became clear and pressing. “Just a few months ago,” Wilson reported, “it became apparent to both the colored and the white women of Evanston that the colored girl here in our community had been absolutely forgotten, especially the transient girl.” The composite “colored girl” and “transient girl” Wilson referred to were likely young women recently arrived from the South Side or from elsewhere in the Midwest or even farther away like the Delta; they were looking for work or intending to visit a friend. Either way, for the so-called transient girl, “there was no safe, wholesome house where she could live while seeking employment or where she could spend even one night. There was no place where she could meet her friends for social recreation.” The “transient girl” described in 1925 could stand for Robbie Shields nearly two decades later. To admit that Black women had been “absolutely forgotten,” as Wilson wrote, is also to say that there was no permitted space for an increasing population of Black women residing in Evanston.4

Where would Shields have gone if North Shore did not exist? Why did it become so important to house the “transient girl,” whether short or long term? Who took on the matter, and how? The archival trace of this encounter between Shields and the North Shore Community House animates what had been an urgent yet elusive problem of housing Black women and girls in urban—and suburban—landscapes in the early to mid-twentieth century. In fact, several of the founders and leaders in the making of the North Shore house had been transient girls themselves. They were sympathetic to the social possibilities and challenges their residents would have been negotiating, and sensitive to the features and logics of space organizing their daily lives.

The North Shore Community House enacted home as “safe space” for Black women’s “sustenance and preservation,” “self-definition,” and “resistance”—as scholars such as Farah Jasmine Griffin, Patricia Hill Collins, and bell hooks have theorized. This rooming house—collectively owned by a Black women’s club—offers what Danielle Purifoy articulates as a “site-based strategy of refuge, political resistance, love, and longevity.” This house, and the women committed to it, collapsed the scales of homemaking, rooming, and building to form a distinct and inconspicuous site for Black women’s living.5

When they characterized Robbie Shields as inferior and unfit to room with or near white women in a dorm, the officials not only wielded the language and position of Jim Crow inspired by their southern constituency, as they said, but they invoked a category of naming, describing, and managing young Black women and girls that had been rumbling in social scientific and reformist discourse in Chicago since the turn of the twentieth century. Scholars, reformers, and community leaders had long been concerned with making sure Black girls and young women grew into proper race women and citizens, lest they become dependent, delinquent, or destitute due to the vices of the city.6

As historian Marcia Chatelain wrote, “Chicago’s thriving reform culture organized itself around black girls and young women’s educational, employment, and social needs,” focusing especially on girls and women newly arrived to the city. Both Black and white women reformers shaped the discourses and methods used to evaluate and determine the risks to and moral fitness of girls and young women emigrating to the city at the beginning of the twentieth century, throughout the Gilded Age, and well into the Great Depression. No matter the specific resources Black girls and women needed—whether homes, schools, or jobs—all Black girls and women “compelled race women, or black social reformers, to refute the disparaging categorizations of black girls that stemmed from the racialized, sexual stereotyping of black women,” including such categorizations as “unbridled” and “deviant,” alongside insinuations of inferiority and unfitness.7

The most successful plans to house girls and women in the city were also some of the most morally determined, modelled after Jane Addams’s brand of reform at the Hull-House Settlement of Chicago. The settlement house, founded by Addams and reformist Ellen Gates Starr in an immigrant and working-class ward on the West Side, became the best-known and most influential urban settlement. As Shannon Jackson noted, Addams and Hull-House residents worked on reform in the broadest sense, from labor reform and juvenile protection to suffrage and housing. They laid the groundwork for much of the programmatic strategy that would be considered “social welfare” in the United States, thus defining the relationship between the state and its polity in the twentieth century. Addams recognized the racialized dimensions of social welfare in its implementation in Chicago but foregrounded the immoral conditions of poverty rather than the structural forms of racism that would inhibit Black girls’ ability to attain quality lives in the city.8

Writing for The Crisis in 1911, Addams explained that “a decent colored family, if it is also poor, often finds it difficult to rent a house, save one that is undesirable, because it is situated near a red-light district, and the family in the community least equipped with its social tradition is forced to expose its daughters to the most flagrantly immoral conditions the community permits.” Here, Addams frames residential discrimination and poor-quality housing as contextual, focusing on the Black family’s proximity to immorality—coded here as a particularly insidious form of urban sexuality and geography—and the family’s inability to protect their daughters from such places. “Yet black reformers,” Chatelain wrote, “even those most steeped in racial uplift thinking, were not eager to endorse the notion that black families inherently lacked ‘social tradition’ and were entirely unable to properly protect their daughters. Black women reformers instead believed that the poor simply needed the right influences to redeem themselves and perfect their families.” In other words, the fate of the vulnerable Black girl was linked to the fate of the Black family, an idea that would continue to dominate social study, social welfare, and social politics in Black communities and in the United States for decades to come. As this discursive cloud formed over Black girlhood and womanhood, the urgent need for resources like housing remained distorted if not totally eclipsed by persistent moral panic.9

By the 1940s, the fear of girlhood delinquency and troubled womanhood centered more and more on Black women and girls, who were increasingly surveilled and criminalized. By 1944, citing statistics from Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis (1945), Chatelain wrote that “African American girls made up 36 percent of girls at the Illinois State Reformatory,” an institution that alarmed social reformists “because it housed girls who were merely orphaned and not criminals.” This tie between orphanhood, criminality, and housing took root earlier in the century, with the Chicago Defender writing in the early teens on the disparity between how white orphans and Black orphans were treated: “That is a most unjust condition of public affairs which gives to a white orphan girl care, education, and training in a school, and then instead of caring for an [African American] orphan girl either farms her out in private homes or sends her to prison.” Black Chicagoans already held the fear that the lack of housing could lead to exploitation and institutionalization.10

But the girls in Drake and Cayton’s study made clear that the availability of housing did not necessarily ensure their safety and well-being. Many of the girls and teenagers nearing adulthood who were interviewed spoke of “early exposure” to sex in the way that reformers and other concerned adults feared. What seemed to be of most consequence to the girls and teenagers was sexual violence from family and community members, sometimes strangers. This kind of violence did not always, or even mostly, happen in the “red light district” that Addams named but inside of buildings and homes, often their own, making clear the dire need for safe housing for Black girls and young women.11

If there was one way for older Black girls or young Black women to seek better conditions for themselves in the mid-twentieth century—including housing, wages, and a kind of independence deemed socially acceptable—then they might have found an opening through domestic work, particularly out in the suburbs. Black domestics were the exception to spatial segregation, often crossing the color line to work and sometimes live within or near their place of employment in white households. Evanston, the home of the North Shore Community House, was one such suburb.

Evanston was considered what Andrew Wiese terms a “domestic service suburb.” Evanston and other suburbs around Chicago attracted affluent white commuters after the implementation of new rail lines in the early twentieth century. As these communities grew, so too did the domestic service population across races. Wiese wrote that by 1940, “African Americans comprised about one-quarter of Evanston’s sizeable domestic service labor force, and domestic and personal service was the dominant job category among black Evanstonians, especially among black women.” Further, “in contrast to patterns among white suburbanites at the time (both wealthy and working class), more than half of black women in Evanston worked outside the home, and a great majority worked in domestic service.” For Black women both newly arrived and already established within Evanston, consistent domestic work created an avenue for modest homeownership in Evanston, providing a basis for “upward mobility, shelter for extended family, and security during times of sickness, accident or old age,” as well as “a greater degree of independence … than any form of tenancy.” Homes in the more spacious suburbs could also provide economic security, achieved by gardening and keeping livestock on the land or by renting out rooms and apartments. Between 1920 and 1940, 25 to 40 percent of Black Evanstonians earned income through renting space to tenants.12

Although domestic work in a place like Evanston provided opportunities for mobility and more space to strategize, the conditions of that work produced risks of harm to Black women on the job. As one teenager shared in an interview with sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, Black girls and women suffered abuse working in a white home, especially in the form of labor exploitation: “My mother wouldn’t even let me work for any white people there,” she said. “I know the first white woman I worked for here. I never will forget, because she worked me most nights to death and didn’t pay me anything.”13

If the North Shore Community House was expected to take in not only local women working in Evanston but any Black girl or woman who needed somewhere to stay, then this was due not only to Northwestern’s racism, but also to the intersecting oppressions of racism and sexism that created the social condition of Black women and girls without developing and sustaining the resources to genuinely serve them. The social issues that emerged as an urgent problem at the turn of the twentieth century became the dominant lens through which to examine and manage Black girls and women—socially, culturally, and economically. The object of the house and the notion of “home”—as site of study, as a safe or unsafe space, as an avenue of employment, as property—anchored the fate of Black women and girls.

In one handwritten and undated note addressed to her local Ebenezer ame Church, Cora L. Watson—one of the North Shore Community House’s leading founders—would try to describe to her congregation just how consequential a rooming house for Black women could be for reasons both clear and concealed: “You would be surprised to know just how many women and girls stop at this House during the year. You would no doubt be surprised to know how many spend their Thursday and Sunday within its cheery walls. Perhaps you would be surprised to know the sacrifice some women have made for this Home.”14

Watson’s repeated refrain—”you would be surprised”—holds an air of mystery and the gravity of evidence unseen. How could it be that her home church did not or could not see the urgent need and demand for housing Black working women and girls in their midst, or that white employers couldn’t see the need to shelter the people they seek to hire? Watson’s tone here could be promotional, building the listener’s anticipation before revealing the thing they did not know they needed. Yet her tone could also reflect respectable constraint, the pulpit an inappropriate place to discuss the “improper,” though widely known, realities of labor exploitation and sexual violence Black domestics could face working in white households. She emphasized the frequency with which Black women and girls “stop at this House during the year,” implying that not all stay, though many do. In the first two years, nearly two hundred women and girls were housed, according to the Evanston Review. Watson specified that these girls spent only their “Thursday and Sunday within its cheery walls,” lodging and socializing for the weekend while working and living elsewhere during the week. Watson might have also felt the need to choose her words carefully; if she told the congregation that the rooming house was open all week, some might have questioned whether the house was a home or a brothel. Watson’s righteously persuasive rhetoric communicated the urgency of housing for Black women and girls as a structural matter, not only a social one, an idea that had long driven the discourse.15

This approach translated. Even the reporter from the Evanston Review caught on. Writing for a white reading audience rather than Watson’s Black church listeners, the reporter described the community house as “an unpretentious social enterprise which has proven its place in Evanston … a home with wholesome surroundings for working colored girls … The support of the home is interracial. Its usefulness in the community is unquestioned. Its needs are moderate … it should never have to ask a second time for what little it requires.” White Evanstonians had a stake in Black women and girls living in the area: they needed workers. So, Watson and others capitalized on this paternalistic desire to meet their own needs.16

What distinguished the North Shore Community House as a model of housing for Black women and girls was its form and its focus. Its mission of housing Black women and girls who needed it was so simple it could be seen as negligible: a home anchored not in the dictates of moral reform (at least not exclusively), nor in the commitments of familial reproduction, nor in the pursuit of profit, but in the belief that Black women and girls ought to be able to live their lives. One might argue that the purpose of maintaining such a house would be similar to that of settlement houses—to influence the residents to prioritize such goals of uplift, mobility, and propriety if they did not hold those aspirations already. Though residents might only pass through North Shore on their way to supporting households of their own, Watson and the women who ran the house would ensure that residents could also stay as long as they needed and desired. In 1975, a newspaper would report that one resident had being living there for more than forty years.17

THE NORTH SHORE COMMUNITY HOUSE was originally named “The Iroquois Community League Home” after the African American women’s club that purchased it. Founded in 1917, the Iroquois Community League of Evanston sought to meet the recreational needs of the girls in the city. Eva Rouse, a Canadian homemaker and a native of Chatham, Ontario, Canada, served as the club’s first president. Rouse was active in the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, meeting frequently with leadership around the city and state to address the needs of African American women and girls amid the first wave of the Great Migration from the 1900s through the 1920s. Rouse and the early members envisioned a community house where girls in Evanston and the surrounding area could find recreation, protection, and guidance.18

By the 1860s, Evanston had a visible, thriving African American population well equipped with the institutional knowledge and capital to sustain its small and rooted community out of which the Iroquois League emerged. By the turn of the twentieth century, Evanston’s Black community had three churches, catering businesses, shoemakers, secret orders, barbers and hairdressers, clubs, an officer on the police force, and a graduate from the local high school. Evanston’s Black population doubled from 4 percent of the city’s growing population by the end of the nineteenth century to 8 percent by 1930. Southern migrants joined Evanston’s extant community of Black Midwesterners and migrants from further north, like Rouse. As historian Morris Robinson Jr. noted, newcomers found work with wealthy white employers who had been relocating to Evanston since the Chicago fire in 1871 and then again after the 1919 race riots, seeking a place to live that felt safter and less violent. Evanston became increasingly racially segregated as more migrants moved in. Before 1900, Robinson wrote, “Negro residents were relatively free to live anywhere in Evanston, including the lakefront. However, new city ordinances and covenants in housing deeds ultimately, over time, forced the majority of Negroes,” both previously settled and newly arriving, “into one area of Evanston” bounded by a canal and two major local roads.19

The Iroquois League Community House, located between Evanston’s African American enclave and Northwestern’s grounds, stood on a corner between a residential street and a main road. Constructed as a Queen Anne, a popular British Victorian architectural style, the house had served as a single-family residence since the late nineteenth century. The home was designed to take advantage of its corner location: two large, angled bay windows maximized the view and natural light on both floors facing the street with no obstructions. With the exception of the windows, it shared a similar design with other houses on the street, leading contemporary architectural historians to believe that these houses were originally built as a subdivision for families.

The Iroquois Community League Home, as an institutional model, took the form of many Black settlement houses that emerged in the early twentieth century in response to the refusal of mainstream settlement houses to assist incoming populations of Black migrants and with the goal to address the needs of Black populations more generally. These homes typically operated like centers, providing safe havens, skill-building opportunities, and free space for community organizing. The Iroquois Community League Home offered Bible classes, instructional classes, and other services. But most importantly, as one Evanston reporter lauded, they offered “sleeping rooms, capable of accommodating up to 15 to 20 girls.”20

As a rooming house in the 1920s, the Iroquois League’s model could have been associated with a number of real estate trends that were going out of favor in the Chicago area: settlement housing, like the Hull House Settlement on the West Side for recently arrived European immigrants; the “slums” and “kitchenette buildings” of the South Side, which began to burst at the seams due to the state halting new building construction in the wake of World War I; and a shortage of the adequate housing promised by predatory job recruiters to lure southern Black workers to the area. The newcomers soon realized that quality living spaces were unavailable to a growing Black working class. Selecting a house with visual and architectural dignity likely helped the Iroquois League revise the image of rooming houses while meeting the need for quality housing for recently arrived young women.21

R. E. Wilson, who published the January 1925 article about the home in the Evanston News-Index, was particularly impressed by the interracial collaboration that made this house possible. Wilson’s article focused more on the white philanthropic patronage and perception of the house than the Iroquois League’s vision or the realities of operating and maintaining the house to meet the swelling need. Rouse and the Iroquois League members probably knew that they would have to unite with white organizations to some extent to appease readers who might not be sympathetic to their cause or their ownership of the house. They joined forces with representatives from Evanston’s white-led Inter-Racial Co-operative Council, whose mission was to “promote friendly understanding with the colored people of Evanston and to assist them in worthy undertakings.” Wilson credited the Iroquois League for originating the idea for the house, although the organization purchased the house under “Iroquois League Inc. for the North Shore Community House” in 1921. Wilson, however, attributed its ownership and control to the cooperative council alone. Either Wilson did not know that the Iroquois League had purchased the house or she felt that the idea of Black women collectively owning this parcel might have been disconcerting or irrelevant to some. Either way, the name “North Shore” placed the interracial commitment at the forefront and kept Black women’s ownership of the house concealed. Though this concealment could be read as a form of erasure, it could also be read as protective, even if unintentionally. The Iroquois League could maintain its front of moral service and shelter for vulnerable women—as benefactors of white benevolence—while meeting the variety of housing needs and desires of “transient girls,” no matter the reason.22

The Evanston News-Index article gave a first look into the life of this new house and its forgotten girls. Wilson was greeted by Bessie Garrison, the resident director at the North Shore Community House. “We are having a little dinner party tonight: two or three of the girls have invited a friend who is studying at the university,” Garrison told the reporter, “but come in and we shall be glad to show you the house and tell you something of what we are trying to do here in the community.” Garrison and Wilson might have spoken beforehand to plan the visit, or Garrison might have been told to expect a visit from a reporter that day. Either way, Garrison and the residents were prepared to present a vibrant image of a sociable, smart, and respectable household of women.23

The reporter was immediately impressed with the social life and physical conditions of the house as she saw it that day. She observed that the living room was “neatly and comfortably furnished,” the dining room table was “carefully set for the party,” and the girls “[cooked] their own meals” in the pantry and kitchen. “As we went up the stairs,” Wilson wrote, “the sound of a Victrola followed us from the room where the girls were entertaining,” and the sleeping rooms “spoke well for the neatness and self-respect of their occupants.” But even beyond the impressive state of the well-kept home, “an invisible something was just as truly present—a feeling of home which those girls, strangers to each other so short a time ago, had succeeded in putting into the house. Everyone was quiet, helpful, courteous and evidently happy.”24

Wilson’s reflection is idyllic in its rendering of the domestic lives of young women who were coming of age under one roof together. She paints a sentimental picture of girlhood that presents the scene of Black girls keeping house together as a marvel. While the reporter’s coverage affirms the work of the clubwoman and the environment they created, she treats the more paternalistic reader to a picture of contained racial and gendered order. In this house, the “transient girl” no longer runs the risk of idleness, vice, hedonism, and materialism. The reporter serves as witness for the public to see how well the girls acted there, how carefully they tended to the space, and how happy they seemed to be. This nonthreatening scene of Black sociality may appease the otherwise concerned reader and galvanize their support for the house. The reader may even be moved to hire these residents to work in their own houses. The successful performance of propriety characterized the rooming house’s early years. But the Iroquois League had more radical plans beneath the surface.

Resident director Bessie Garrison’s long-term vision for the house aligned with a working-class consciousness that emerged among Black women workers and organizers after World War I. Garrison, coming to North Shore from her previous position with the Colored ywca, took interest in new labor practices that could improve the lives of Black women. The reporter wrote that Garrison’s vision included a clinic for children, a day nursery, and a welfare center in collaboration with the public library. Her most ambitious goal was to add an annex or to turn one floor of the house into a training school for domestic workers, “where they may be taught, among other things, efficiency, right standards of conduct, habits of courtesy, the right use of leisure and the dignity of labor.” Such a space reflected the training school model to which African American club women and organizers had already been accustomed. But Garrison’s approach could also shift the emphasis from racialized, gendered, and classed expectations and biases around Black women’s duties to institution-building and labor organizing that centered Black women’s work.

Historian Dorothea Browder wrote that Black women capitalized on new attitudes toward labor and industry during World War I in efforts to secure opportunities for themselves where there previously were none. They did this through strategic alliances between settlement and Christian-based organizations for Black women, and with allies from wartime industrial programs—for domestic workers, laundresses, seamstresses, and tobacco and garment factory workers—from which Black women were excluded. When Garrison envisioned a new section of the house for domestic work, she was not necessarily referring to more training for Black women to work in white homes, even though that form of housework initially might have drawn her residents. Rather, Garrison might have wanted the residents and women in the surrounding Black community to sharpen and employ their industrial skills, domestic or otherwise, and organize on behalf of better labor opportunities and conditions, especially ones outside of white households. With Garrison’s shift in emphasis from behavior to labor, we can see how she, and perhaps others in the Iroquois League, took Black working women’s self-respect as a given, focusing instead on the house itself as a site for practical security.25

Placing emphasis on the house, rather than on the residents’ respectable behavior, would prove critical for the club in the coming years. Though founded in record time and initially well supported by allies and community members, the Iroquois League struggled financially. In two years since opening North Shore’s doors, the club faced the possibility of losing the house altogether. In response to financial crisis, club member Cora Watson pivoted the club’s attention from the residents to the property itself.

FOR CORA WATSON, there was no question that Evanston needed this house. That need would persist as long as young Black women needed work; as long as they sought out and enjoyed opportunity, leisure, and mobility in and outside of Evanston; and as long as places like Northwestern’s dorms or other lodging houses in Evanston continued to refuse rooms to Black Americans. Watson was a southern migrant, schoolteacher, and domestic worker herself. She had come to Illinois from South Carolina in 1914 with her husband, Moses, a carpenter and building contractor, and not on her own like many of the young women staying in the house (whether wed or unwed). Watson, her husband, and their five children lived a few houses away from the North Shore Community House on Garnett Place, the second Black family to move onto the street. In an interview, Watson recalled the moment when she and her husband decided to purchase a home on that street, though white neighbors objected. “There was this sign on the street, ‘For Sale.’ The whites had a house for sale. I saw it often, when I would get off … the ‘El’ coming from Chicago. I decided I would just ask, out of curiosity. They tried to get a white buyer, but the family said they would sell to anyone if they had half the money down. I went back to Greenwood [South Carolina] and sold the [family] house to get the money for a down payment.” They procured a loan from a local trustee and, with the money from the old house, purchased their house on Garnett.26

Watson’s story reflects a common one among Black migrants nationally, a story of familial networks passing information, exchanging resources, and securing property. But her involvement in the rooming house breaks away from this primarily family-centered narrative of quality living and imagines what quality life could look like for girls and women providing for themselves and others without property at their disposal, without a familial unit at its core, and beyond the transactional relationship of landlord and tenant. Although Watson never served as a resident director of the North Shore Community House like Garrison, she was likely as much a part of the life of the house as those living within it. Her sensitivity to working girls and their needs, her commitment to the house, and her grasp of the economic and architectural stakes of the building became consequential to its survival as a home not for paternal procreation, labor, or profit, but exclusively for communal living.

By 1926, the Iroquois League and the house were facing bankruptcy. Until that point, the house had been operating through member support. The club received many new members after they opened the house in 1924, and that swell in membership helped to support mortgage payments. But once the Great Depression hit and the future of the house appeared uncertain, more and more members withdrew their support and only a few of the executive members remained, “making it impossible to meet the longtime payments on the building and other necessary obligations,” according to one club narrative. Watson was one of those remaining members, encouraging the rest by warning them that they could not afford to lose what they had gained. That year, when the club elected her as their new president, she shared her vision for what the house could become: “I saw a beautiful building on this corner with club rooms, auditorium, gymnasium, dormitory … a building that unborn generations would be proud of. A building that would be a monument to club women and an asset to the race.”27

In their first efforts to prevent bankruptcy, Watson and fellow members fundraised and received contributions from allies in Evanston who continued to see the need for housing for Black women and girls. The club still struggled to pay their increasing property taxes near the end of the decade, until a local lawyer—hearing them speak during an Inter-Racial Cooperative Council meeting—stepped in to assist. The lawyer helped them to attain nonprofit status, thus removing their tax burden. By 1929, the Iroquois League had officially paid off the mortgage. In June 1931, Watson ended her term as president, having achieved her primary goal. In her end-of-term remarks, typed and delivered to the Iroquois League, Watson celebrated the strong financial foundation the house sat upon: “Instead of a mortgaged and taxed Home, we have a Home free from all indebtedness, and exempted from taxes; the fire insurance paid up to September 1933, all bills paid up to-date, and one thousand and two hundred dollars in the bank to the credit of the Iroquois.” She thanked the group for their trust, cooperation, and assistance in “carrying forward the high ideals of ‘lifting as we climb,'” rooting the house within the broader mission of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs by invoking the club’s well-known motto. The story was told and retold in anniversary teas and news articles throughout the first two decades of the home. Club members who came just after Watson likely understood the house to be a symbol of the club movement’s racial uplift mission when they commissioned an official photograph of the house in 1933.28

The photograph commemorates the idyllic “home away from home” and “monument to club women” that the Iroquois League first sought out and that Watson saw fit to protect. Compared to the distant view from across the corner, published in the 1925 Evanston News-Indexarticle, this photograph offers the proximity of a portrait. The bright bricks on the façade glow, and the window treatments and columns appear freshly washed. With its windows on every side and corner, the house appears warm and inviting through the bare trees. The club added a fence between their grounds and the corner, signaling safety and security, and the photographer’s low angle makes the home appear grand and impressive. Finally, the studio added color tints to the grass and the roof, adorning the house and the grounds the same way they might embellish the faces of their sitters. The professional, stately, and textured portrait of the house shows just how determined Watson and the members were to present its legacy as a quality place to live and as a monument to Black women’s institution building. If the image did not communicate this intention, Watson, club secretary Mary Rogers, and treasurer Ora Casselberry made the point clear in a caption preserved behind the image: “This Home is doing a twofold work. Aside from giving our girls a home, it provides work for our people. This club pays out hundreds of dollars every year for work done by our people: the matron, the janitor, the carpenter, decorator, and plumber. You can see that this organization does a good work.”29

The residents would come and go, as they should: freedom of mobility, accessibility of housing for one night or many, and a safe and secure environment for the many ways young Black women needed to spend their days—that was the point. But for Watson and her counterparts in the Iroquois League—all trying to figure out how to retain the home as a safe space—property was paramount.

In the following years, new members and new leadership saw value in Garrison and Watson’s original plans to enlarge the house for more rooming and more activities. The idea was controversial. Some thought the building was satisfactory as it was; some thought the timing for remodeling was bad; and few wanted or could afford to organize the expansion campaign required to fund the new annex. So, in 1951, the club invited Watson back to help build out what they started. This time, fundraising would be easier. The club and the house had been well established, and it still served an important need for Black women and girls who worked in the area and for those who were turned away from other establishments. The problem for Watson and the Iroquois League would not be lack of proper support but zoning.30

The club’s emphasis on property would prove significant as they weathered changing contexts in housing and living space. The post–World War II moment saw increased interest in single-family homes across classes, and the prevalence of new factory jobs made sources of income such as rooming units less necessary for families. In an effort to develop land to meet this single-family housing demand and to inhibit multifamily and multiuse expansion, the city enhanced their inspection and licensing protocols. According to one late-twentieth-century Evanston planning report, zoning hearings in the postwar era frequently revealed “fears concerning poor maintenance or conversion to rooming houses” as a sign of decline. The North Shore house was not for one individual family’s—or even the club’s—profit, and its existence as a rooming house for women and girls might have remained recognizable as an important civic service and philanthropic endeavor. But given this change in the social, economic, and cultural climate, the home may no longer have been recognizable as an urgent or desirable form of housing.31

The club did in fact succeed in completing the new annex in 1957. But the house’s inspection and licensing documents from that decade suggest that Watson and club leaders struggled to meet the standards of the new zoning ordinances on rooming houses, from the number of residents they were allowed to have to the kinds of building changes they were permitted to make. They became responsible for making significant repairs on a house constructed nearly a century earlier, long before residential codes had been put into place in Evanston. They sent in license renewal applications that were either rejected or not even listed as received, and they continued to seek out community support for structural repairs of the house. Cora Watson and her daughter Anna moved into the home during its tenure as the community house. Anna Watson purchased the house from the Iroquois League in 1973 and continued operating it as a private multifamily residence. According to public records, the house was sold in 1983.32

The North Shore Community House provides an illustrative example of how one group of Black women imagined and produced space for the population they were committed to serving and how they preserved that plan in an ever-changing landscape. The women who owned and operated the house saw themselves as committed first to the well-being of transient young women and girls and eventually came to see that their best interests would be served less through efforts toward the behavioral or moral “betterment” of residents than through the maintenance and survival of a place they could call home.

Jovonna Jones is an assistant professor of African American literature and culture at Boston College, working at the intersections of Black aesthetics, Black feminist criticism, and the built environment. Her writing has been published in Aperture, Boston Art Review, Callaloo, Souls, Southern Cultures, and MCA Chicago. Her current project examines Black women’s tenant organizing in Boston.

NOTES

- “Northwestern Dorms Bar Negro Students,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), Real Times Inc., August 14, 1943, 5; St. Clair Drake, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1945); “Northwestern Sued For $50,000 In Dorm Ban,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), Real Times Inc., December 11, 1943, 7.

- Evanston History Center, 45th Annual Mother’s Day House Walk-By, May 10, 2020, https://secureservercdn.net/45.40.149.159/596.3a3.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Housewalkby_Excerpt.pdf; “Northwestern Dorms Bar Negro Students.”

- “Oldest Founded Girls Home,” June 19, 1975, unattributed newspaper clipping, Iroquois League of Evanston Collection, Evanston History Center.

- R. E. Wilson, “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women,” Evanston News-Index, January 30, 1925, Iroquois League Collection (1952–1972), Evanston History Center.

- Farah Jasmine Griffin, “Who Set You Flowin’?”: The African-American Migration Narrative (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 9. Griffin argues that “safe space” for Black women should be understood as an attempt for “sustenance and preservation” as opposed to a site of self-definition, as Patricia Hill Collins originally argued with her theory of safe spaces, or as opposed to a site of resistance, as bell hooks argued in her theory of homeplace. See Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought (London: Routledge, 1990), and bell hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Boston: South End Press, 1990). For more analysis on the house as social, economic, and cultural capital in the twentieth century—including a gendered reading—see Gwendolyn Wright, Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981), and Margaret Garb, City of American Dreams: A History of Home Ownership and Housing Reform in Chicago, 1871–1919 (University of Chicago Press, 2005). I use the terms home and house specifically, and not household, because I want to foreground the interior and exterior objecthood of the place, and where Black women’s engagement with that kind of object falls in these broader discourses about race, gender, and space. Rooming houses were considered as households on the census in the early to mid-twentieth century, insofar as the residents all shared the same address and did not live in individuated apartments (where each would have had their own bathrooms and kitchens). Though logistically the rooming house would be a household, it would be interesting to consider what the form of a rooming house—especially North Shore in its communal intentions—does to social and cultural registers of households, particularly as an American cultural picture anchors itself in the nuclear family and the single-family house, and as social scientists and policymakers continue to refuse Black poor and working-class tenement and apartment dwellers the status of households at all. For more on the connection between the nuclear family, the single-family home, and suburban development in postwar America, see Lynn Spiegel, Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001). For analysis on structural framing of Black space as foreclosed to the category of household, see Saidiya V. Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019). Danielle Purifoy, “Call Us Alive Someplace: Du Boisian Methods and Living Black Geographies,” in The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity, ed. Camilla Hawthorne and Jovan Scott Lewis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023), 41.

- Marcia Chatelain, South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 14–16.

- Chatelain, South Side Girls, 10–12.

- Shannon Jackson, Lines of Activity: Performance, Historiography, Hull-House Domesticity (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 5.

- Jane Addams, “Social Control,” The Crisis, January 1911, 22, quoted in Chatelain, South Side Girls, 11; Chatelain, South Side Girls, 11.

- Chicago Defender, 1913, quoted in Chatelain, South Side Girls, 30, 143.

- Chatelain, “Do You See that Girl?: The Dependent, the Destitute, and the Delinquent Black Girl,” and “Did I Do Right? The Black Girl Citizen,” chap. 1 and chap. 4 in South Side Girls.

- Andrew Wiese, “Black Housing, White Finance: African American Housing and Home Ownership in Evanston, Illinois, before 1940,” Journal of Social History33, no. 2 (1999): 429–460, 433.

- Chatelain, South Side Girls, 153.

- Cora L. Watson, undated letter, Iroquois League Collection (1952–1972), Evanston History Center.

- “Helping the Colored Girls,” Evanston Review, January 14, 1926, 1.

- “Helping the Colored Girls,” Evanston Review.

- “Oldest Founded Girls Home.” Watson and her daughters moved into the home at some point during its tenure. Her daughter Anna Watson purchased the house from the Iroquois League and continued operating it as a rooming house until she sold the home sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s. The resident mentioned in this clipping was still living there at the time of publication in 1975, more than forty years.

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library, “The Iroquois Community League Home, Evanston, Illinois,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed April 24, 2024, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-838f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library, “Mrs. Eva Rouse,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed April 24, 2024, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-ebf2-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

- Morris Robinson Jr., Through the Eyes of Us: True Experiences of Lives and History Shared by Evanston’s African-American Community: Oral History Compact Disk and Chronological Timeline (Robinson Group, 1998), 1–3 in the written companion to the film, CD-ROM (74 min.).

- Charles Hounmenou, “Black Settlement Houses and Oppositional Consciousness,” Journal of Black Studies 43, no. 6 (September 2012): 646–666; “Eva Rouse,” Evanston Women’s History Project, December 31, 2019, https://evanstonwomen.org/woman/eva-rouse/; Wilson, “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women.”

- Horace R. Cayton, “Negro Housing in Chicago,” Social Action 6, no. 4 (1940).

- Wilson, “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women”; copy of deed ownership on 1125 Ayars Place, from 1894 to 1918, with handwritten revisions, likely made by a club officer (Evanston History Center). The handwritten revisions include the history of the Iroquois League’s ownership from 1921 to 1973, when the house was purchased by Anna Watson, Cora Watson’s daughter, for rooming house purposes. At the top, “Ayars” is crossed out and “Garnett” is written to the side, signaling the street name change in the late 1910s or early 1920s.

- Wilson, “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women.”

- Wilson, “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women.”

- Dorothea Browder, “Working Out Their Economic Problems Together: World War I, Working Women, and Civil Rights in the YWCA,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14, no. 2 (April 2015): 243–265.

- Women of Evanston Personal Information Sheet on Cora Lee Watson, Evanston Women’s History Project, 1973, Iroquois League Collection, Evanston History Center; Wiese, “Black Housing, White Finance,” 429–460, 439.

- Ruth J. Steele, “Story of Iroquois League’s Community House,” undated, Iroquois League Collection (1952–1972), Evanston History Center. This history was likely written and delivered to the audience at the organization’s 1963 Anniversary Tea, as Ruth J. Steele was listed in the program of events as presenting an oral history of the club and their efforts.

- Cora L. Watson, “The President’s Farewell Address,” June 1931, Iroquois League Collection (1952–1971), Evanston History Center.

- Typed caption attached to the back of the Hill Photo Service photograph, 1922, Iroquois League Collection (1952–1971), Evanston History Center.

- Steele, “Story of Iroquois League’s Community House.”

- “Land Use: Part I of The Source Book on The Comprehensive General Plan. Living Areas, Working Areas, Institutional Areas,” Evanston Plan Commission, 1972, 11.

- Evanston Women’s History Project, accessed April 24, 2024, https://evanstonwomen.org/organization/iroquois-league/.

IMAGE SOURCES:

Art 1

War relief, YWCA, ca. 1914–1918, catalog.archives.gov; cumulus clouds during golden hour, by Dewang Gupta, New Delhi, India, unsplash.com; ocean water, by Yogesh Gosavi, unsplash.com; clouds, by Gong TY, unsplash.com; stars and galaxy as seen from Rocky Mountain National Park, by Jeremy Thomas, unsplash.com.

Art 2

Girl from group of Florida migrants near Shawboro, North Carolina, on their way to Cranberry, New Jersey, to pick potatoes, by Jack Delano, Library of Congress; Chicago Club and Fine Arts Building, Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, by Ken Lund, Flickr.com, CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED; Rookery Building, Adams and LaSalle Streets, Chicago, Illinois, by Jay Galvin, Flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; Railway Exchange Building, Chicago, Illinois, Wikimedia Commons; Reid Murdoch Building, Chicago, Illinois, by David Ohmer, Flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; curtain wall high rise building under white clouds and blue sky, by Scott Web, unsplash.com; gold leaf halo handmade by Nancey B. Price.

Art 3

Women from “Scott and Violet Arthur arrive with their family at Chicago’s Polk Street Depot, August 30, 1920, two months after their sons were lynched in Paris, Texas,” published in the Chicago Defender on September 4, 1920, via Wikimedia Commons; sky by Pixabay, pexels.com; “Community House Meets Need of Colored Women,” Evanston News-Index, January 30, 1925, courtesy of the Evanston History Center; azalea bush, by Tatters, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; luggage trunks at North Weald Station, Essex, by Acabashi, Wikimedia Commons.

Art 4

[Woman looking out of a window], by Angelo Rizzuto, LC-DIG-ppmsca-69875, Anthony Angel Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress; three pink tulip flowers, by Sixteen Miles Out, unsplash.com; Globular Cluster Messier 4 (M4), ESA/Hubble, NASA.

Art 5

“A Home For Women And Girls,” Hill Photo Services, Evanston, Illinois, 1933, from the Iroquois League Collection, courtesy of the Evanston History Center; tigertail swallow butterfly, by Dulcey Lima, Lisle, IL, unsplash.com; flowers, by Heather Bozman, pexels.com; tamarindo, Wikimedia Commons.

Art 6

Meridian Hill Park, 42-SPD-18, Record Group 42: Records of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, National Archives; Seattle jungle, by Wonderlane, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; Flowering Azalea bush, by Tatters, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; Rookery Building, by Jay Galvin, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0 DEED; Chicago Club and Fine Arts Building, by Ken Lund, flickr.com, CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED.