This series of over-sized tintypes is a rumination upon a relationship with a person and a city. Using metaphor, allegory, and the re-interpretation of a few facts, these images re-stage events and themes, and recreate certain atmospheres from a period of sixteen years. They are an idealized record of my relationship with my partner Brian Waitman and the years we spent together in New Orleans.

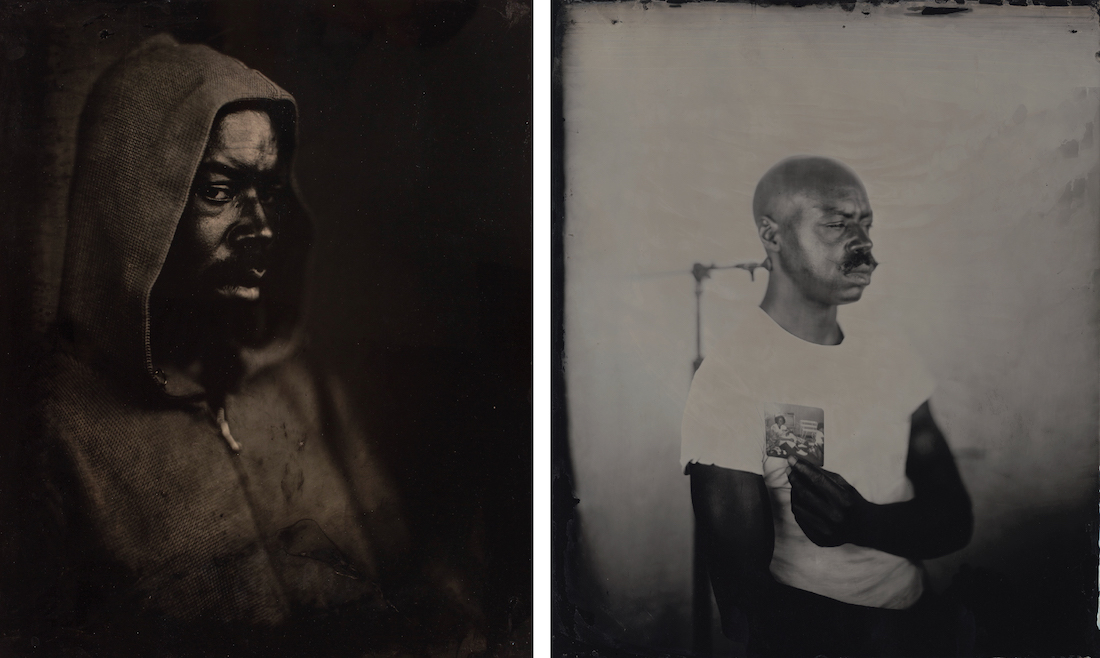

I wanted to make something that represented the idea of trying to know someone—and the feeling of knowing them well and then, at times, not at all. Focusing on issues of race, boredom, sexual identity, poverty, beauty, and a hurricane—among other things—the series expresses the desire and frustration and occasional contentment of trying to find intimacy with another human being.

I wanted to make something that represented the idea of trying to know someone—and the feeling of knowing them well and then, at times, not at all.

The tintypes, which measure 19 × 23 in. and 20 × 24 in., were made with the assistance of Bruce Schultz, who produces tintypes at Civil War reenactments across the South. I was attracted to the idea that you can only make one tintype of an image. They are singular. No usable negative, no way to reproduce them. In some ways, even though they are made on metal, this makes them more fragile. The images are, in fact, negatives seen on a dark background—on the black surface of the blank tintype, they appear as positives.

For this project, Schultz fashioned a camera obscura by attaching a Cooke 530mm lens to a red ice fishing tent, making the tent into a camera, which was subsequently used as a darkroom to process the image. Using something on this scale enabled us to make these plates much larger than tintypes are typically made. At this large size, everything in the process is deliberate. A good day for us, working eight hours, might produce two successful images. Schultz lives in Lafayette, three hours away. It was not often that he could actually be in New Orleans, so there was a lot of time to contemplate what the next image would consist of before we could all work together again. You have to consider every action you take. You need to slow down and concentrate and imagine many possibilities before you move forward.

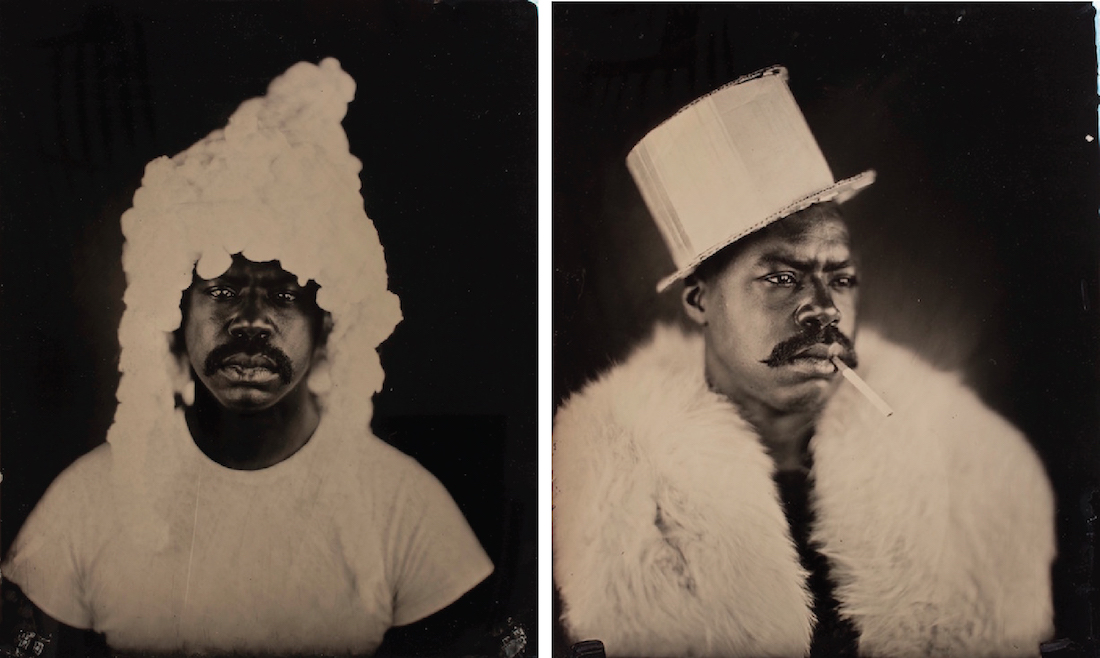

Man with his head in the clouds (left), 20 × 24 in., 2014. The first plate we made features Brian wearing a wig constructed of cotton balls, which he had made for Carnival in 2013. Seeing it, I thought he looked like a colonial judge. But I also thought of each of those cotton balls, and the history of black people and cotton in the South. There was something absurd about that wig and the ideas of justice and history it brought to mind—the disenfranchised sitting in judgment of their oppressors. All of the images in this series were made in New Orleans.

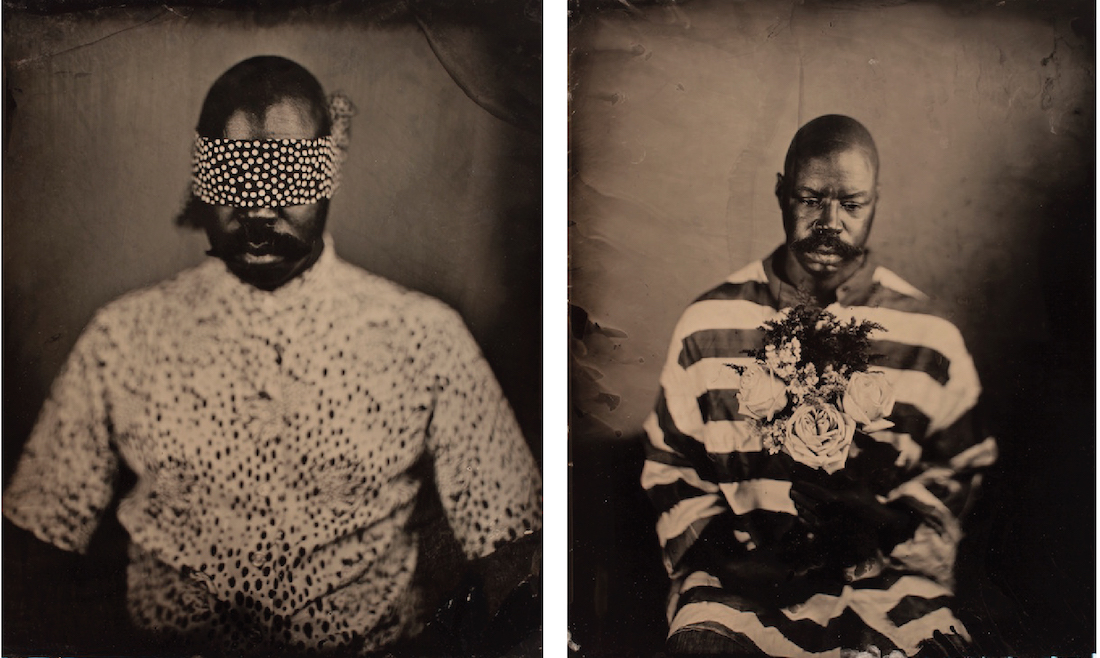

Mr. High Pockets (right), 19 × 23 in., 2014.

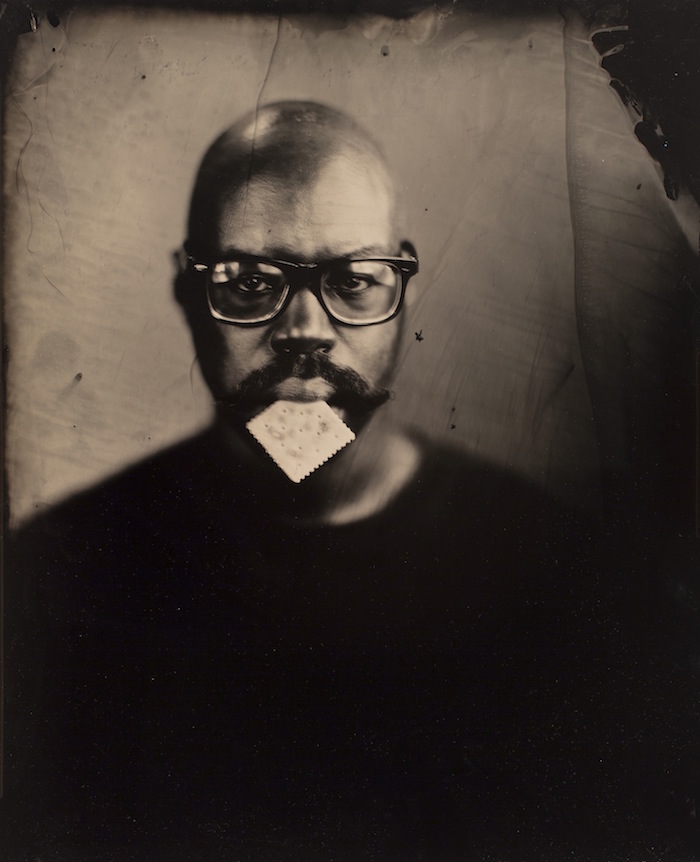

Cracker (20 × 24 in.), 2014. Brian was brought up by his grandmother. She lived in a small town in Florida. I asked him if we could go and visit her, and after putting me off a couple of times, he told me that he didn’t think it would be a good idea. He said that his grandmother hadn’t had a good experience with white people. He told me one time that “cracker” was the worst thing you could call a white person. It never seemed to me to have the same ugly, melting quality as the word used by Caucasians to disparage black people. What I remember growing up were the two words that did seem to have some effect: “white boy,” said as if spitting something distasteful out of the mouth. It was the tone and the inflection of those two words that made them potent. Still, its power was not even close to that of the other, uglier word.

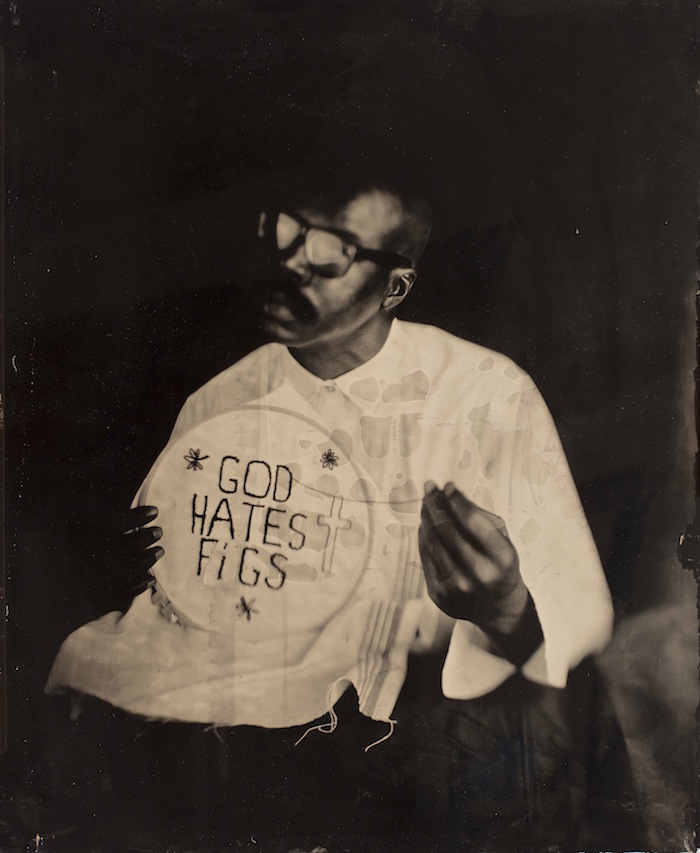

A Westboro sampler (20 × 24 in.), 2015. The words “God Hates Figs” are stitched onto a piece of fabric. My mother was nice enough to stitch it for us, backward, as the tintype process reverses everything. I had been looking at photographs of the group from the Westboro Baptist Church in Kansas, images of their demonstrations at funerals in particular. In one, there was a young anti-protester who snuck in among them and held up his own sign, subverting the hatred around him with the change of a single vowel.

Shoes fill up with water (left), 19 × 23 in., 2014.

The thief’s journal (right), 20 × 24 in., 2015.

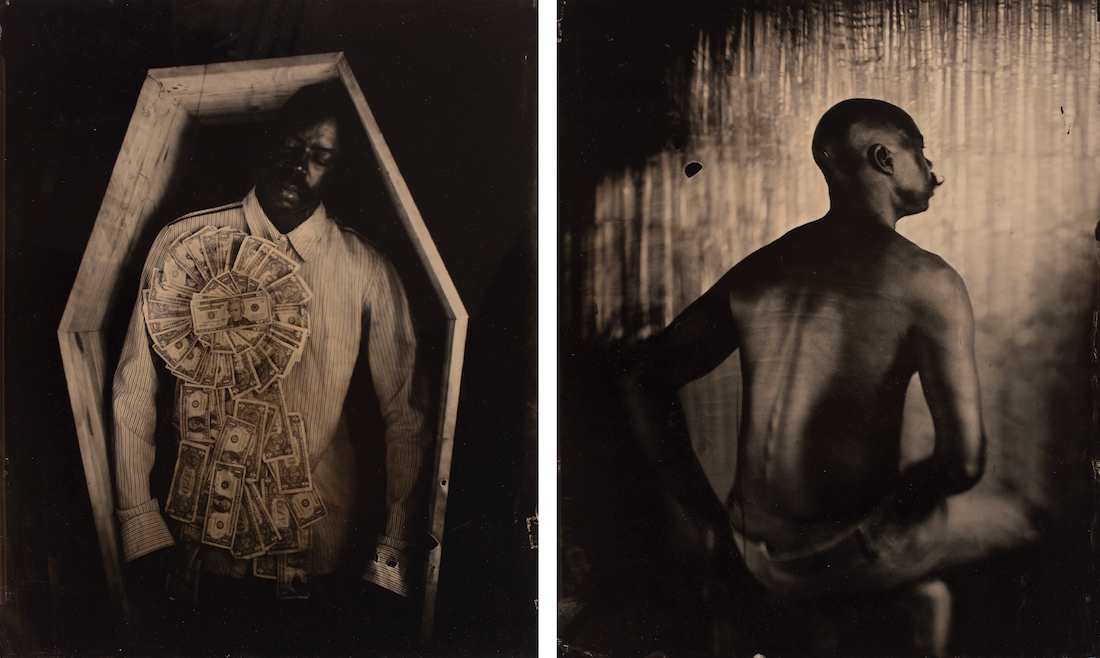

Beer tab hair shirt (19 × 23 in.), 2014. This image shows Brian in a shroud of beer tabs that he made over many months. We went through a period of drinking too much, and drinking on the cheap. Brian would save the tab from every can of beer, and with a single small length of wire attach it to a loose piece of window screen from an old porch door. It was a sort of meditation for him to ponder each and every one of these aluminum tabs as he affixed them, one at a time, to the wire net. The palm frond is a symbol of a Catholic martyr.

Sixteen (left), 20 × 24 in., 2015.

Plays upon muted strings (right), 20 × 24 in., 2015.

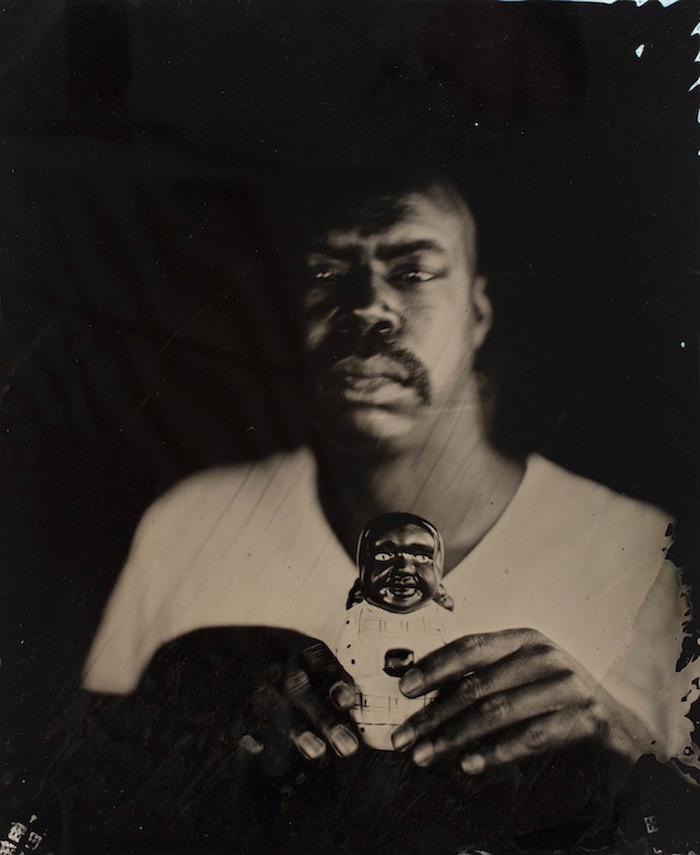

Katrina mammy doll (19 × 23 in.), 2014. When the hurricane hit in 2005, I was on the West Coast. Brian evacuated and ended up in Texas. He stayed overnight with the elderly grandparents of one of his friends. The grandmother went and dug through her belongings and found this doll to give Brian. She had bought it on a visit to New Orleans when she was a teenager. She gave it to him to comfort him and remind him of home. It amused him to be gifted this object, a borderline racist souvenir, from a white woman. The bottom read, “Made in Japan.”

The long walk (left), 19 × 23 in., 2014.

Althea (right), 20 × 24 in., 2015.

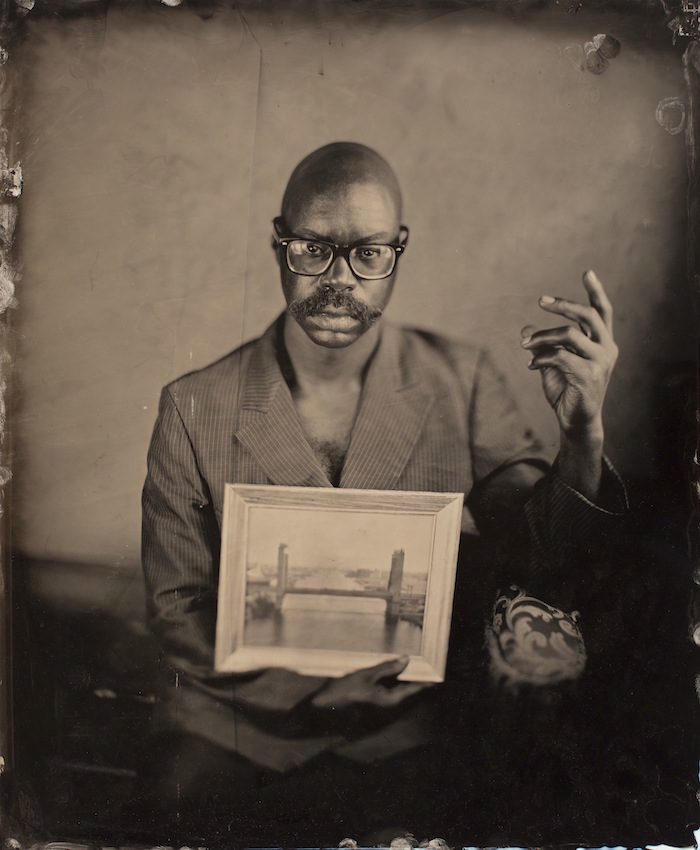

Bridge of paper, bridge of iron: Danziger (20 × 24 in.), 2015.

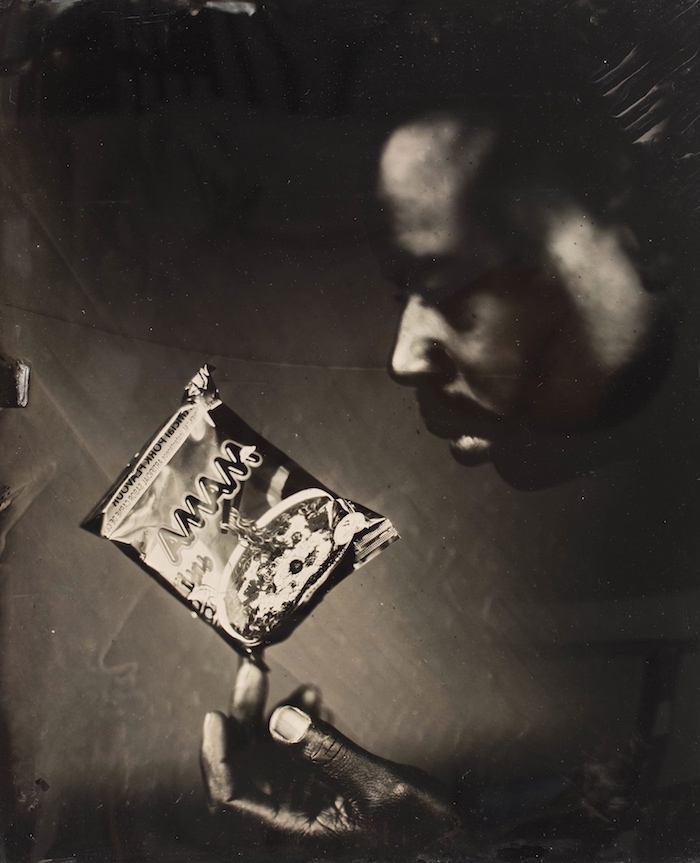

St. Claude diet (19 × 23 in.), 2014. Brian and I were often broke, and it affected our eating habits. The part of New Orleans we lived in, down river from the French Quarter, was for many years without a decent grocery store, especially after Hurricane Katrina. We would find a little of this and that at corner stores and liquor marts. Most of these places were along the commercial corridor we lived next to, St. Claude Avenue. The image of Brian “balancing” a package of cheap ramen noodles on his finger is a reference to this, and a play on the idea of a healthy diet.

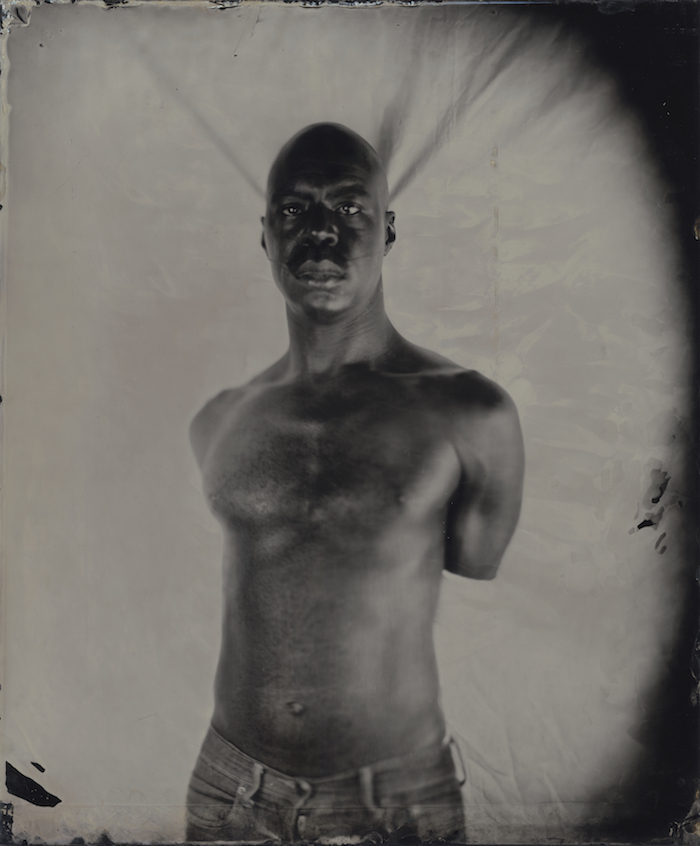

Venus de B (20 × 24 in.), 2015. We made this image after we had broken up. It simply refers to Brian’s disappearing from my life.

This essay appears in the Backward/Forward Issue (vol. 25, no. 1: Spring 2019).

Kevin Kline is a film photographer best known for his street portraits of the people of New Orleans. In the last five years, he has worked with early processes: tintypes, ambrotypes, and glass plate negatives. His work was shown at the Halsey Institute (Charleston) and the New Orleans Museum of Art earlier this year. He lives in New Orleans.