"Our task is not the simple one of re-building demolished houses and ruined cities. If only the material shell of our society needed repair, our designs might follow familiar patterns. But the fact is our task is a far heavier one; it is that of replacing an outworn civilization." —Lewis Mumford

Among the expected turkey legs, fireworks, cotton candy, and Ferris wheels, Dorton Arena presents a familiar yet extraordinary sight at the North Carolina State Fairgrounds. Defined by its double hyperbolic arches, the building looks like an alien spaceship and brings to mind similarly shaped structures in sci-fi flicks or at equally iconic contemporary sites, such as the Gateway Arch in St. Louis (1963), the Trans World Airlines (TWA) terminal in New York (1962), or the Sydney Opera House (1959). Predating these structures by almost a decade, the visionary and influential form of Dorton complicates the fairgrounds’ seemingly ordinary landscape. Originally established in 1853 with the mission to exhibit and reform agricultural practices in North Carolina, the fairgrounds became the harbinger of the land grant institution North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (1887), now North Carolina State University. In order to reignite this mission, Dorton Arena was completed in 1952 to become a showcase of agriculture and technology and to bring together people from all walks of life in the aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II. Now, Dorton’s unusual form looks conspicuous and estranged from its context of cow and horse trailers, gun and knife shows, and RVS. It seems intentional yet incomplete; visionary yet adolescent; built and, at the same time, left unbuilt.1

It seems intentional yet incomplete; visionary yet adolescent; built and, at the same time, left unbuilt.

This issue of Southern Cultures frames its theme, Built/Unbuilt, not so much around the transformation of contemporary sites, as it might seem, but around landscapes and modernities left glaringly incomplete. While many of these sites have come to be viewed as parts of ordinary landscapes, the issue’s theme allows us to identify and bring attention to how extraordinarily unfinished they remain. The issue includes explorations of nineteenth-century public spectacles celebrating natural resources, science, and technology; the long futures of nuclear waste sites and their inevitable environmental ramifications; and Carrie Mae Weems’s powerful photographs of herself confronting spaces of forced production, segregated education, social power, and reform. These accounts reveal that the South’s architectural landscapes have always been and continue to be incomplete, representing an abandonment of the initial aims and aspirations of proponents of a progress-oriented New South.

Dorton Arena, with its unusual form and structure, provides an excellent window into the unfamiliar and the incomplete at the North Carolina State Fairgrounds, leaving those who are willing to take a second look with daunting questions. How did it land on the North Carolina State Fairgrounds? Why would anyone design such an extraordinary structure for a livestock exhibition hall owned by the State Department of Agriculture? Was its form simply an extravagant reflection of the Ferris wheels, circus tents, and the ever-popular fireworks displays at the annual state fair, or was there more to this structure than populist pomp and circumstance?

The usual narrative credits the building’s namesake, Dr. J. Sibley Dorton, with its vision. A professor of veterinary medicine who became the director of the state fair in 1937 (soon after the fair’s move to its current location in west Raleigh in 1927), Dorton called on his colleague Henry L. Kamphoefner, the recently appointed dean of the new School of Design at North Carolina State College, to help him select the right architect to design a visionary arena and modern fairgrounds that would showcase North Carolina’s agricultural and industrial products on a year-round basis. In 1939, the New York World’s Fair had succeeded in restoring America’s faith in industrial production in the aftermath of the Great Depression. Following World War II, state fairs across the country quickly followed suit to light the beacon of modernization, progress, and technology in every citizen and state in the Union.2

Fittingly, this symbolic project came at the very beginning of Kamphoefner’s twenty-five-year career as the dean of the College of Design—a test for him and the school. Kamphoefner appointed one of his newest lieutenants, Matthew Nowicki, chair of the Department of Architecture, to the project. Nowicki was to work with the longstanding architect of state and federal projects, William H. Deitrick, to lead a design team to develop a new master plan. Among the new faculty that Kamphoefner had brought with him to NC State, Matthew Nowicki and his wife, Stanislava (Sandeka) Nowicki, were arguably among the most controversial figures, given the social and political contexts of the Cold War and the soon-to-come McCarthy investigations. The Nowickis were two of the most prominent designers of their generation in interwar Poland. Their debut in the United States came with Matthew Nowicki’s involvement in the design of the Polish Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Surviving the war as part of the Polish resistance, the Nowickis returned to the United States in 1945 as cultural attachés. Serving on the international design team of the United Nations, Matthew Nowicki was recognized as the talented young architect of the UN’s Assembly Building. This involvement led to the couple’s collaboration with Eero Saarinen, by then also a well-recognized young architect, on the design of the Brandeis University campus, which served as a model for a number of postwar campuses around the world. It was in this context that the Nowickis met Lewis Mumford, who connected them with NC State.3

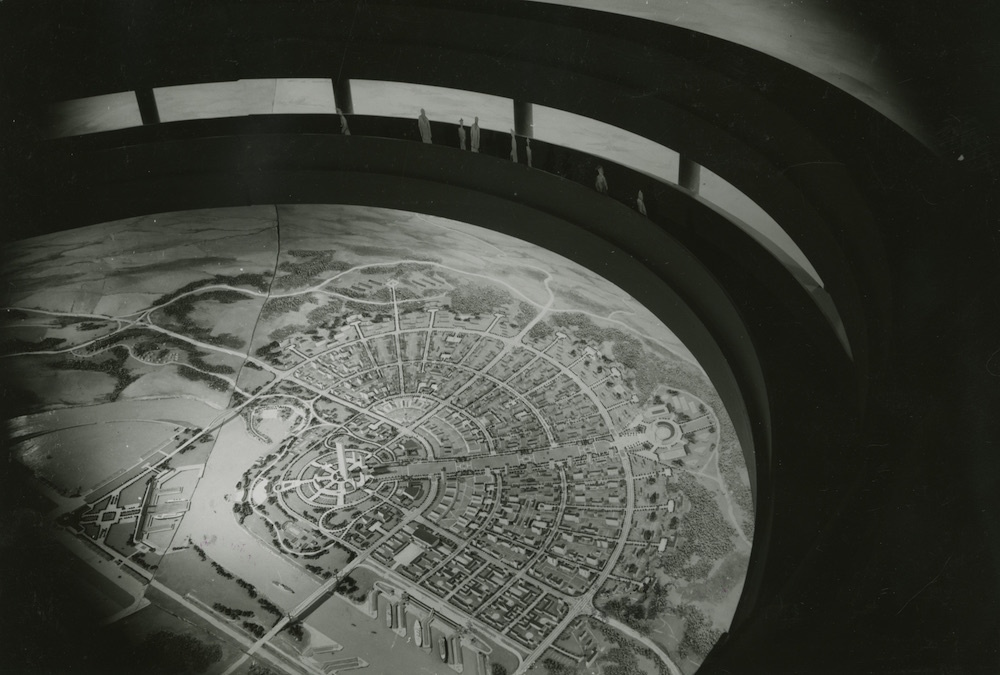

Mumford was a sought-after lecturer at the American Institute of Architects events in Washington, DC, and drew Kamphoefner’s attention with his thoughts on architecture, planning, and the postwar world order. Mumford assigned an important role to architecture in creating the type of civic spaces that would prevent the reemergence of fascism and would bring together a society otherwise fragmented by industrialization and overspecialization. In his book Technics and Civilization (1934), Mumford provided a historical critique of the social consequences of industrial production. At the same time, he embraced the potential of science and technology to create a more cohesive and advanced democracy. As demonstrated in his contributions to Henry Dreyfuss’s Democracity exhibition at the New York World’s Fair, he believed that electrification and the automobile, along with a national highway system, provided the key components of a healthier and more democratic society.4

The South held an important role in the realization of this new social and spatial experiment. Infrastructure and power generation projects carried out by the Tennessee Valley Authority and New Deal programs had set the stage for this new model of regional development. The promise of this New South had also drawn Kamphoefner to the region. In order to sow the seeds of these ideas in the minds of future generations, he invited Mumford to provide a series of lectures as a primer to architecture and engineering students. Chancellor John W. Harrelson supported this idea, as it paralleled federal programs to balance technical education with courses in the humanities. To augment these initiatives, Mumford recommended Matthew Nowicki as the founding chair of the Department of Architecture. The Nowickis, who had fought fascism at close range in Poland, shared his ideas on postwar reconstruction. Raleigh, as the center of a new and thriving region, and NC State, as the locus of new technologies, including atomic energy, was a perfect node from which to instill the foundation of a more ethical and sustainable future.5

Raleigh, as the center of a new and thriving region, and NC State, as the locus of new technologies, including atomic energy, was a perfect node from which to instill the foundation of a more ethical and sustainable future.

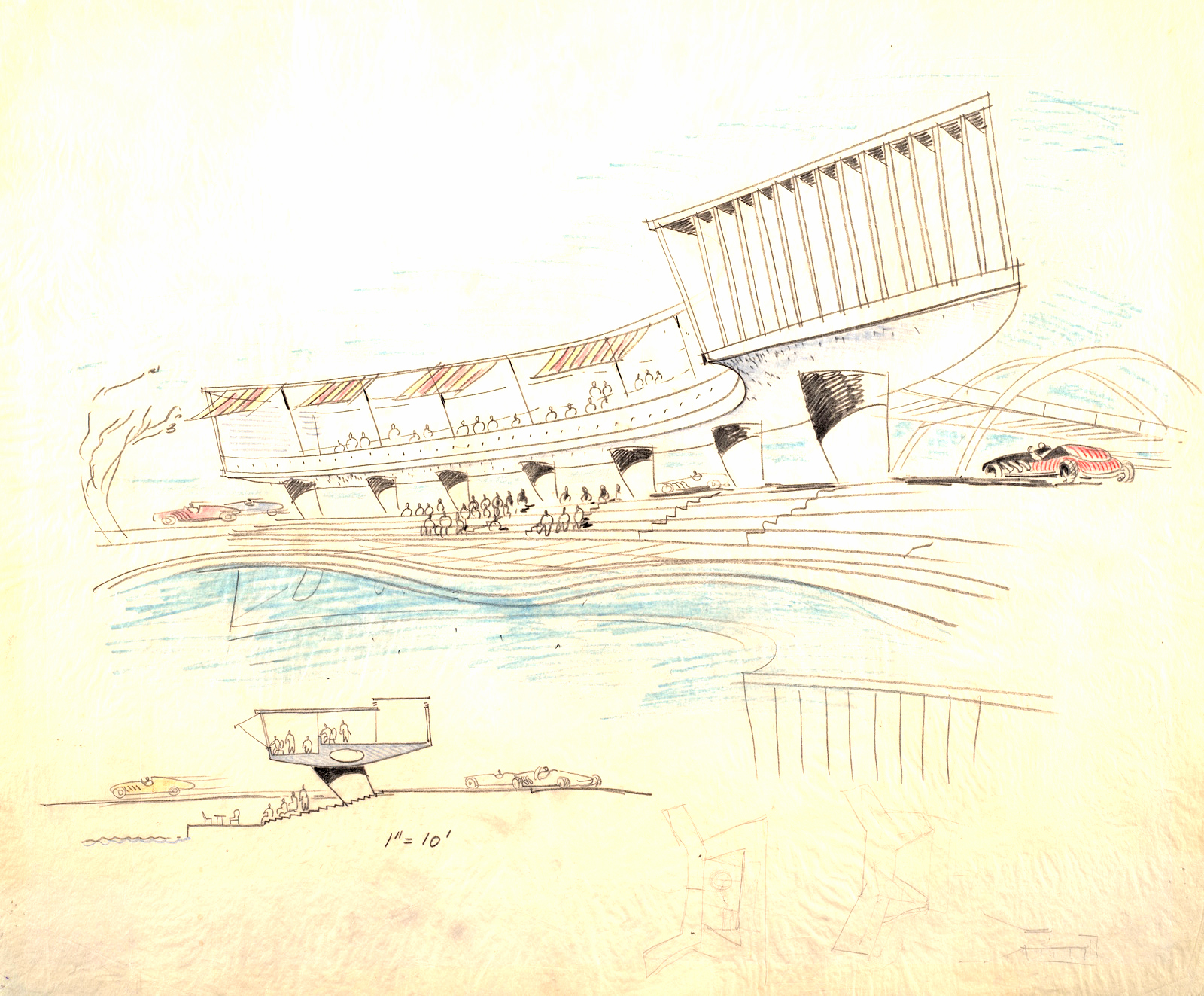

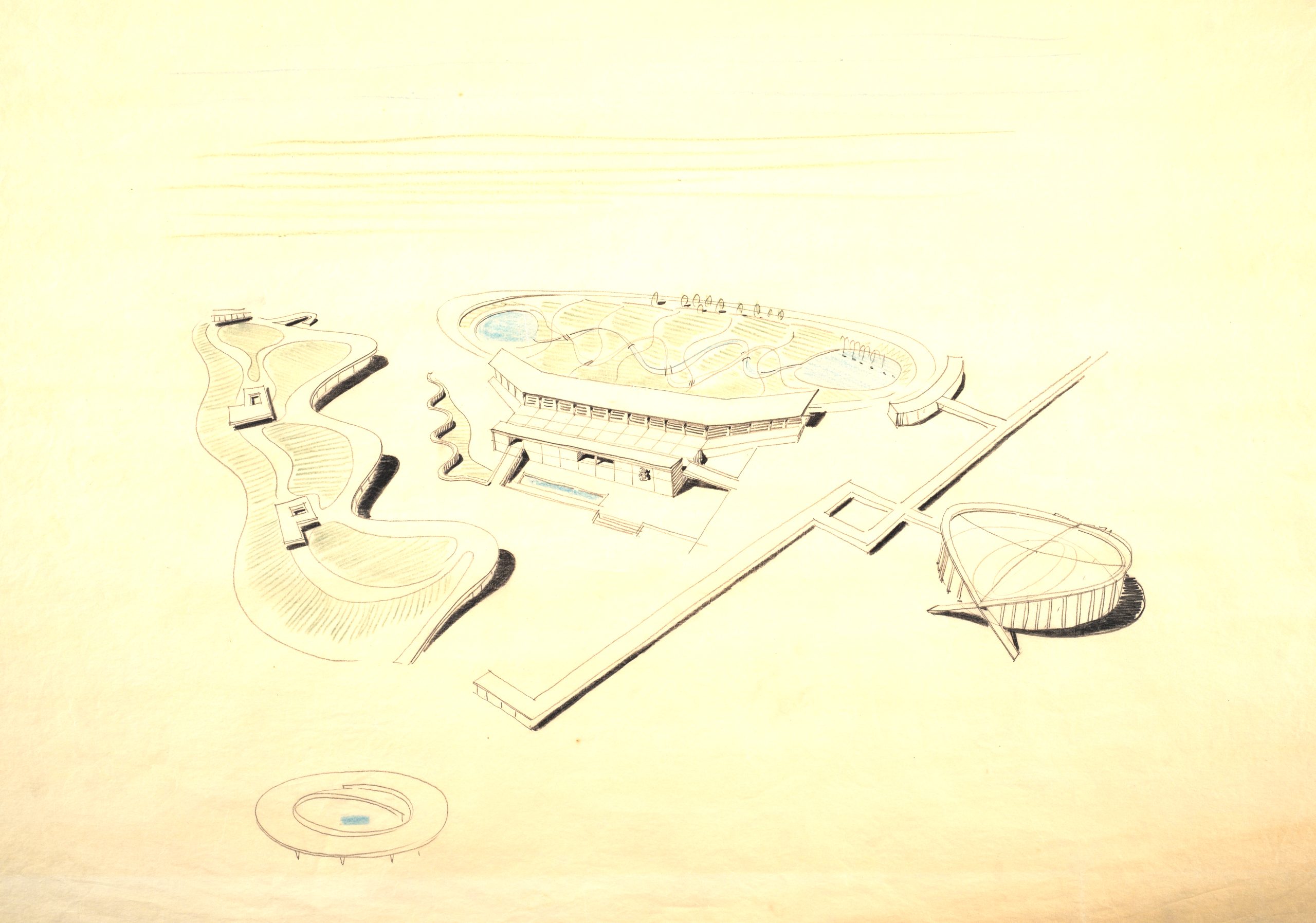

The master plan for the fairgrounds was one of many important projects that the Nowickis took on during their short tenure in North Carolina. Among these were the new NC State Student Union, the Chavis Heights and Halifax Court low-income housing developments, the clubhouse of the Raleigh Country Club, and the master plan for the new capital city, Chandigarh, India. The Nowickis’ scheme for the fairgrounds included Dorton Arena, a 9,500-seat livestock exhibition hall; a racetrack for cars and horses with a park in the infield and grandstands with ten thousand seats; and a sports stadium for one hundred thousand spectators.

The design’s spatial organization and proposed function embodied Mumford’s and the Nowickis’ emerging ideas on civic centers. It was to be a place that transcended social, racial, and economic divides and celebrated the emotional life and aspirations of a community. Along with other key planning ideologues of the postwar period, Mumford formulated the civic center as a modern monument. Prior to the war, Mumford had proclaimed the death of the monument, declaring that stones erected for the rich and the powerful were for the static civilizations of the past. He believed that “civilization today . . . must follow the example of the nomad.” Continuity, he asserted, existed “not in the individual soul, but in the germ plasm and in the social heritage.” The civic center was to emerge as a new monument representing the agricultural, material, technological, and labor forces as dynamic components of a diverse, interconnected community.7

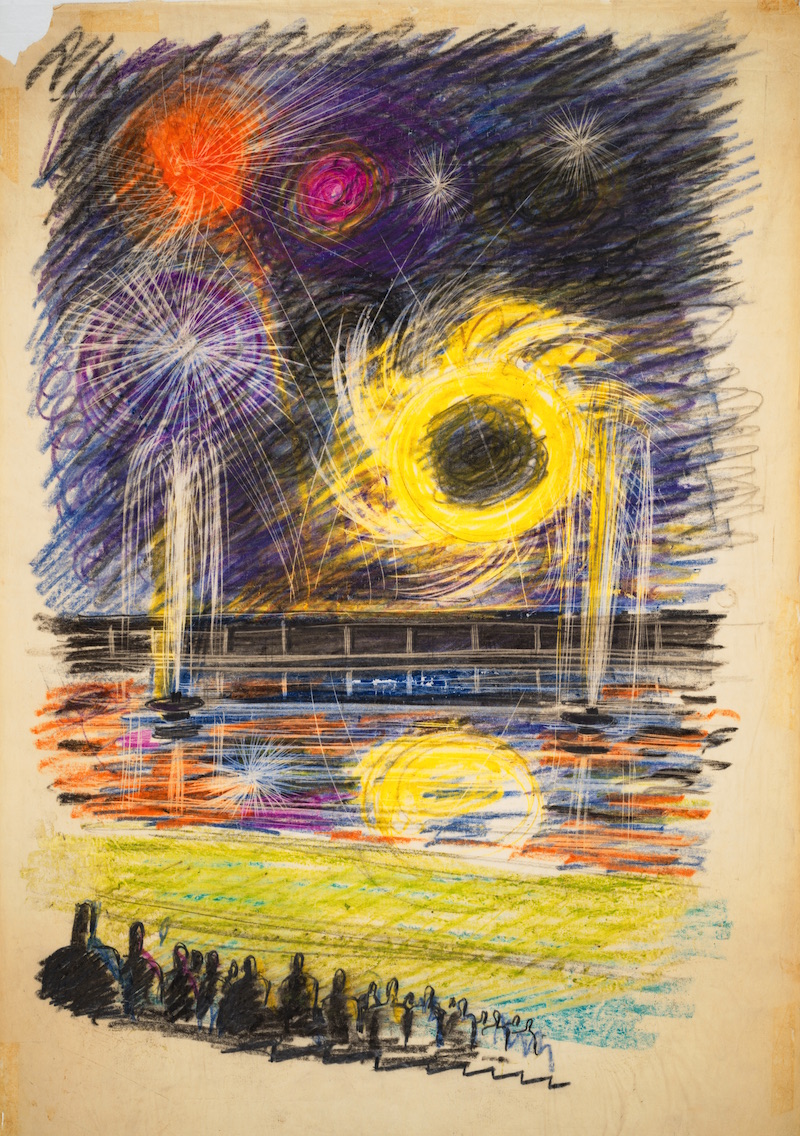

Nowicki’s curvilinear forms for the arena and the racetrack’s grandstand were embodiments of the idea of the civic center and sought to introduce the public to possibilities of a technologically advanced and socially cohesive society. The aim of Dorton Arena was to restore people’s faith in the power of collaboration between the sciences, technology, and agriculture; this would be the place where the farmer’s kids met those of the scientist. Nowicki’s drawing of fireworks displays that families could watch from the grandstands of the racetrack conveyed the social function of this new type of monument.

This would be the place where the farmer’s kids met those of the scientist.

Soon after completing his drawings for the fairgrounds, however, Matthew Nowicki died in a tragic airplane crash on his way back from India, where he was working on the Chandigarh project. Although Dorton Arena would be built based on his drawings, the social and technological ideals that Mumford and the Nowickis had put forward would prove to be too challenging for the wider public. Waldemar Debnam, a radio host at WPTF station in Raleigh, framed Mumford’s book as communist discourse. Despite Kamphoefner’s continued support, Mumford gave up his vision for Raleigh and returned to his teaching position at the University of Pennsylvania. Stanislava Nowicki, left alone in a male-dominated department, followed Mumford to Penn within a few years. The automobile that Mumford had championed became a key instrument in facilitating suburban sprawl, creating one of the most unsustainable models of land use and development and changing the face of the United States and the world. Kamphoefner, along with other members of his faculty, served a predominantly white community and built their houses near country clubs and white suburbs. The modern schools, built under separate but equal laws during the 1950s and the early 1960s in Raleigh, Charlotte, and various state counties, served as instruments of hypersegregation and real estate development, dividing populations by race, class, and space rather than bringing them together.8

The positioning of the new fairgrounds west of downtown Raleigh and near the I-440 beltline can thus be seen as one of the early indicators of Raleigh’s suburban expansion and of white flight, which also manifested through the relocation of a number of the state’s cultural and educational institutions, such as the North Carolina Museum of Art. Viewed in this sixty-year context, Dorton Arena is out of place and its initial aims unrealized. It stands as a monument to an incomplete modernity and to what we, as a society, didn’t build during an opportune time of relative prosperity. Taking our cue from Carrie Mae Weems’s photographs, we might confront these sites and reclaim their promise of a cohesive modern society. A closer look at their incompleteness allows us to see them—and, by extension, ourselves—as we are.

This essay introduces the Built/Unbuilt Issue (vol. 27, no. 2: Summer 2021), guest edited by the author.

Burak Erdim is associate professor of architectural history and design at North Carolina State University. His research traces the operations of transnational planning cultures and his recent book, Landed Internationals: Planning Cultures, the Academy, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, was published by the University of Texas Press (2020).

- Lewis Mumford, The Social Foundations of Post-war Building (London: Faber and Faber, 1943), 9.

- Melton A. McLaurin, The North Carolina State Fair: The First 150 Years (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 2003), 40–41.

- Catherine W. Bishir et. al., eds., Architects and Builders in North Carolina: A History of the Practice of Building (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 350–353; Burak Erdim, Landed Internationals: Planning Cultures, the Academy, and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2020), 153; Tyler Sprague, “Eero Saarinen, Eduardo Catalano and the Influence of Matthew Nowicki: A Challenge to Form and Function,” Nexus Network Journal 12, no. 2 (May 2010): 249.

- Mumford, Social Foundations; Lewis Mumford, “Social Consequences of Atomic Energy (1953),” in Interpretations and Forecasts: 1922–1972 (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), 307–312. Lewis Mumford, along with other members of the Regional Planning Association of America, wrote the script for the 1939 film The City, which accompanied the Democracity exhibition. Ralph Steiner and Willard Van Dyke directed the film, Morris Carnovsky narrated it, and Aaron Copland composed its music.

- Lewis Mumford, The South in Architecture: The Dancy Lectures, Alabama College, 1941 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1941). Kamphoefner would later chronicle new southern architecture in a book he put together with Edward and Elizabeth Waugh; see Edward Waugh and Elizabeth Waugh, The South Builds: New Architecture in the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960). Henry L. Kamphoefner, Raleigh, to Lewis Mumford, New York, April 25, 1948, Henry L. Kamphoefner Papers, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University, Raleigh; Lewis Mumford, “The Life, the Teaching and the Architecture of Matthew Nowicki,” Architectural Record, part 1 (June 1954): 141.

- Mumford, “The Life, the Teaching and the Architecture,” part 3 (August 1954): 172.

- Lewis Mumford, “The Death of the Monument,” in Circle: An International Survey of Constructive Art, ed. J. L. Martin, Ben Nicholson, and Naum Gabo (New York: Praeger, 1971), 263–271; Eric Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 150.

- Chancellor J. W. Harrelson, NC State, to W. E. Debnam, WPTF Radio Co., July 11, 1952, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University, Raleigh. Edward “Terry” Waugh, whom Kamphoefner brought with him from the University of Oklahoma to NC State, established the School Design standards for the Department of Public Instruction and designed a number of schools in Raleigh, including Sherwood Bates and Frances Lacy Elementary Schools as well as Daniels Junior High School (now Oberlin Middle School). Hutchins Landfair, “Unequal Spaces: Segregation and School Modernization in Raleigh, North Carolina 1920–1964” (master’s thesis, University of Virginia, 2016).