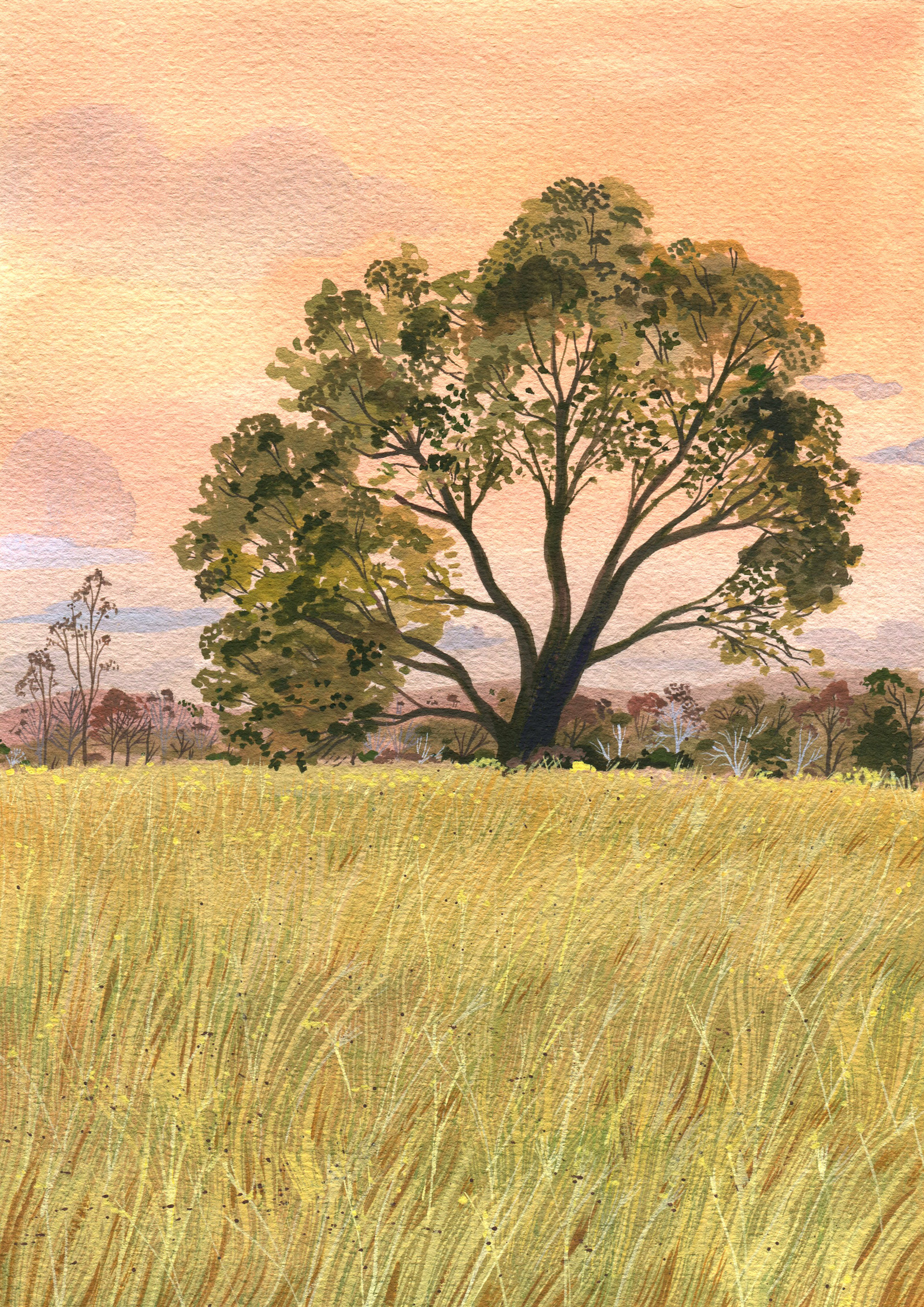

Spacious skies. Alabaster cities. Shining seas. Purple mountain majesties. Fruited plains. Amber waves of grain. America is beautiful. That’s what I learned from singing Katharine Lee Bates’s unofficial national anthem as a child. Yet growing up in middle Georgia, I didn’t see much of that. I looked out on my native terrain, flat and worked-over, and saw housing developments, self-storage units, big box stores, a massive Air Force base, scraggly loblolly pines, pigweed and pokeweed, sassafras and sumac—and a golden grass growing in waist-high clumps all over the landscape. I took my dog mouse-hunting and played hide and seek with friends in “the field”—an infrequently mowed area two miles from my house—until a developer replaced it with a huddle of diminutive houses and tiny lawns. Together with “the woods”—a drainage area to the back of my house sufficiently overgrown to have good-sized trees, along with the requisite brambles and poison ivy—and “the lake”—a large puddle that attracted ducks, geese, and tadpoles—the field was a key feature of our neighborhood natural playground. Never having seen the prairie or gazed upon our national greatness from Pike’s Peak, I assumed that all that golden grass was “amber waves,” and we had those.

They were not, of course, amber waves of barley or wheat, but of broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus). I might be forgiven the misapprehension. There is a superficial resemblance. But broomsedge and grain were worlds apart. Grain fields were cultivated spaces, beautiful because of their amber color and their contrast with purple mountains and azure sky, but also, as Bates saw it, because they represented mastery, plenty, and prosperity. Broomsedge was uncultivated, the plant that came up when you didn’t plant anything, the quintessential unintended landscape. It indicated a deficiency of agricultural acumen and an unpromising future. The common name “poverty grass” was ambiguous, meaning either that it grew up in poor, infertile fields, or in the fields of poor people. Of course there has always been considerable overlap between the two.

Broomsedge was uncultivated, the plant that came up when you didn’t plant anything, the quintessential unintended landscape.

It was ironic, then, that I saw beautiful amber waves in lands that were barren and spent. In my misapprehension I unwittingly highlighted the contrast between Midwest and South, between the warm and loveable “breadbasket of America” and the nation’s original sinner, endowing the country with its ugliest agriculture and a labor system to match it. But irony, as David Foster Wallace famously pointed out, is “critical and destructive, a ground-clearing,” and also “singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks.” Irony offers a pleasant critical distance for the writer. I am foregoing that pleasure and wading right into the broomsedge sea in an effort to recover the plant’s forgotten stories. In the 1850s, broomsedge was an ecological and rhetorical marker for poor—and poorly tended—farmland; in the 1920s, several novelists featured it in debates about the South’s agricultural future; in the 1950s, in the midst of the “bulldozer revolution,” pioneering southern ecologists studied the grass as a key component of old field succession.1

Like Homo sapiens, Andropogon virginicus is a colonizer, always looking for more space. But unlike us, who seem to be always looking for new ground to use up, broomsedge colonizes old land, growing up in the ruins. And so broomsedge is not just a plant of the southern past but of the southern future. Looking back at three moments in southern history, the 1850s, 1920s, and 1950s, the broomsedge–human nexus shows us how frequently hope and anxiety have been fellow travelers in the southern past, and how closely they have been tied to the region’s soils, airs, waters, and biota. As we limp into the 2020s, our post-agricultural southern future, with this agrarian past echoing in our ears, broomsedge sounds a strangely hopeful note in the midst of much anxious dissonance.

Broomsedge is little-known, although almost everyone who has visited or lived in the South has seen it somewhere. And the plant is not much mentioned by scholars, despite the fact that it is nearly as widespread in the historical record as it is in the southern landscape. According to the great American grass expert Alfred Spear Hitchcock, Andropogon virginicus is a native bluestem bunchgrass in the same “tribe” as sugarcane and sorghum. Up close, broomsedge is characterized by “culms erect” or stems, clumped “in rather small tufts” with “sheaths glabrous [smooth] or more or less pilose [covered in long soft hairs] along the margins.” When it blooms the “inflorescence [is] elongate, narrow” with “inflated tawny to bronze spathes,” a “rachis very slender, flexuous, long-villous,” and a “sessile spikelet” with a “delicate straight awn.” That is to say: an upright grass with mostly smooth blades, long narrow flowers on slender stems, enclosed in golden-brown leaves. Look for it, Hitchcock advised, in “old fields, open woods, sterile hills, and sandy soil.” From a distance, throughout the growing season, it looks like any other grass. And then in late autumn, when the landscape around it turns ragged and dull brown, its flower stalks transform those old fields and sterile hills into golden meadows. They remain that way throughout the winter and into the early spring, when the ground greens again.2

Broomsedge is little-known, although almost everyone who has visited or lived in the South has seen it somewhere.

By the 1850s, the South was at the tail end of an epochal agricultural transition from native to imperial agriculture, from hunting, foraging, and slash-and-burn farming in the sixteenth century to acres upon acres of temporally and spatially uninterrupted cotton fields in the nineteenth. For agricultural reformers who critiqued this transition in the mid-nineteenth century, , the evidence of the South’s environmental and social ruin was visible and tangible. The forests, as ash, were in the soil; the soil, as runoff, was in the rivers and bays; the solid southern farmer, now peripatetic, was out West. Contrary to the mythology of antebellum southern tradition—much of which was created by twentieth-century nostalgia-peddling northern and southern whites eager for sectional reconciliation—southern plantations were as much get-rich-quick soil-mining operations as they were genteel demesnes.3

It was in this context that broomsedge first became what we might call an object of interest. Agricultural reformers used it as a kind of shorthand for southern ignorance, indolence, wastefulness, and the impending ruin of southern civilization. As early as 1821, one North Carolina reformer, Charles Fisher, complained to the Rowan Agricultural Society in Salisbury, North Carolina, that southerners “completely exhaust our soil by an unvaried succession of crops; and when it can produce no longer, we turn it out into fields, let it wash into gullies, and grow up with pines and broom sedge [sic], that never failing symptom of exhaustion. This is the common fate of our fields; the system that is defacing our country, and ruining our lands.” An 1832 letter to the Farmers’ Register from Columbia County, Georgia, lamented the “wretched appearance of our exhausted lands, presenting an alternation of gullies and broom-sedge [sic].” In 1853, Frederick Law Olmsted—who went on to be the nation’s most famous landscape architect—took a tour of the South and described Virginia’s “old fields” as “a course, yellow, sandy soil, bearing scarce anything but pine trees and broom-sedge [sic] . . . sassafras bushes and blackberry-vines, which nature first sends to hide the nakedness of the impoverished earth.” Almost twenty years later, a southern reformer wrote in 1872 of “the many evils of the all-cotton mania,” especially the exhaustion that resulted from no rotation, and described his own project of reform on a small farm where “the land was worn almost to barrenness. Stunted pine saplings and broom-sedge [sic] were the only natural growth.”4

Broomsedge had a brief moment as a potential component of a restored southern agriculture. The plant is a close relative of big bluestem (Andropogon gerardi), a grass of the Great Plains much celebrated for its beauty and value as forage, and a few farmers thought that broomsedge might also sustain livestock. In the 1890s, some insisted that broomsedge was a decent pasture grass, and even that cattle preferred broomsedge hay to other kinds. A few reformers acknowledged that broomsedge might be able to “sustain the life of your cattle” but most were at pains to discourage its use. “Let the broomsedge cover with its friendly shadow the old fields,” North Carolina horticulturist Wilbur Fisk Massey wrote in 1892, “but then let us get away from broomsedge forever. It is the best that nature can do to hide the havoc bad farming has made, but when we start in the restoration of old fields, let us get away from the badge of their exhaustion.”5

For Massey, like other southern agricultural reformers, the stakes were high. The agricultural New South depended on making a break with the wasteful past of staple crop farming, characterized by skimming the soil of its nutrients during a few years of tobacco or cotton production, and then abandoning it for “virgin” lands further west. Massey drew on a southern agricultural reform tradition that was already nearly a century old by 1892. Cattle represented one way to make such a break, since they needed pasture, unplowed and hence less erosion-prone, and because they produced manure. There were other reform possibilities in play, too—apples, wine grapes, peaches, tomatoes, and timber—but in each case would-be improvers were looking for a way to reshape the slave-powered plantation system that had dominated the South since the 1850s. The emancipation of those enslaved peoples in 1863 had done little to change the basic staple-crop framework.

Broomsedge did not, in the end, live up to this promise. Cattle can eat the tufts of grass in the early spring while it is still green and tender, but they don’t prefer it. For this reason, it is generally considered to be a pasture weed, albeit easily managed. According to one study, a little bit of fertilization, to increase the density of legumes and other grasses, along with some well-timed mowing or grazing, to keep it from going to seed, was enough to nearly eliminate broomsedge from a field. For all its apparent vigor and indomitability, in other words, broomsedge is actually quite fragile. One researcher discovered that even without competition, half of a test plot of broomsedge seedlings had died after three years, with the remaining dead by year seven. Broomsedge apparently relies upon prolific reseeding on unoccupied land in order to dominate the landscape in amber waves.6

But broomsedge’s uselessness did not translate into meaninglessness. Massey’s depiction of broomsedge both as a “badge” of exhaustion and as a merciful covering of the South’s various sins—like God clothing Adam and Eve in the skins of animals in the wake of their own postlapsarian expulsion from the Garden of Eden—would be taken up by several novelists of the 1920s and 1930s. Like Massey, Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow had seen southern fields waving with broomsedge during summers in the Virginia Piedmont; she, too, viewed those fields with a certain ambivalence. And in the 1920s, she was one of several fiction writers to cast a jaundiced eye on the grass.

Broomsedge’s uselessness did not translate into meaninglessness.

In 1925, Glasgow published what would become her most famous novel, Barren Ground, which made her, among other things, a kind of poet laureate of broomsedge. The novel chronicled the life of Dorinda Oakley, a rural southern woman who transformed a worked-out Virginia farm into a successful dairy operation, and who married only late in life, and then more for comfort than for love. Glasgow divided the book into three parts, each named for a common resident of the old fields of the Virginia Piedmont: Broomsedge, Pine (Pinus taeda), and Life-everlasting (Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium).

Broomsedge is ubiquitous in the story. All across post-Civil War rural Virginia, Glasgow wrote, “broomsedge was spreading in a smothered fire over the melancholy brown of the landscape.” The grass changed with the weather and season. It was “cinnamon-red in the sunshine,” ivory under “scudding clouds,” yellow-green in the spring rains, a “splendour of colour” in autumn sunsets, sea-like during a storm: “Then the quivering would become a ripple and the ripple would swell presently into rolling waves. The straw would darken as the gust swooped down, and brighten as it sped on to the shelter of scrub pine and sassafras.” Amber waves indeed.7

It was a harsh beauty, though: broomsedge remained an indication of Virginia agriculture in decline. Confined to the borders of a well-tended farm, broomsedge marked the wild edge, the “not-farm” of southern wilderness. Overtaking an entire field, broomsedge suggested ill health. As the aging carpenter Matthew Fairlamb of Glasgow’s novel puts it: “Broomsage ain’t jest wild stuff. It’s a kind of fate.” Later in the novel, Jason Greylock, a young doctor and one-time-beau of Oakley, attributes to broomsedge a kind of personhood. “No, I want to get away, not to spend my life as a missionary to the broomsedge,” he confides to Oakley. “I feel already as if it were growing over me and strangling the little energy I ever had. That’s the worst of it. If you stay here long enough, the broomsedge claims you, and you get so lazy you cease to care what becomes of you.”8

The broomsedge does not claim Oakley. She reclaims the broomsedge. During a stint in New York City which allows her to recover from her jilted love for Greylock, she has a vision and a dream of her family’s worn-out and abandoned farm, and begins studying books about dairy farming. As Oakley reads, she finds herself envisioning “the renewal of promise in the land; the sowing of the grain, the springing up, the ripening, the immemorial celebration of the harvest. She saw the yellowing waves of wheat, the poetic even swath falling after the mower.” And then she returns to the farm and begins turning an old field “run to broomsedge” into a pasture for her new herd of jersey cattle.9

Broomsedge is also a fixture in Erskine Caldwell’s 1932 Tobacco Road, a novel about the pathologically poor Jeeter Lester and his family. It’s where Lester’s daughter Pearl hides from her husband. It’s where he buries his (possibly still alive) mother after she’s run over by a car. And above all, it’s what burns when it’s time to plant cotton. As Lester puts it in a long speech to his son-in-law Lov:

“When the winter goes, and when it gets to be time to burn off broom-sedge in the fields and underbrush in the thickets, I sort of want to cry, I reckon it is. The smell of that sedge-smoke this time of year near about drives me crazy. . . . when a man stays on the land . . . he’s right here to smell the smoke of burning broom-sedge and to feel the wind fresh off the plowed fields going down inside of his body.”

Lester can’t get anyone to give him credit to plant any cotton, so fields of “brown broomsedge” are fallow land, potential livelihood that are just out of reach. After six or seven years of this, Jeeter is depressed: “to be compelled to live and look each day at the unplowed fields was an agony he believed he could not stand many more days.”10

Caldwell’s vision was bleak, perhaps excessively so. Glasgow was also critical of the plantation South, but she also believed in an alternative rural future. For Caldwell in Tobacco Road, in contrast, the plantation South was an abject failure, leaving little but ruin in its wake. Unfulfilled promise, year after year, ultimately yielded a “kind of fate.”

One of the books that Glasgow likely consulted as she wrote Barren Ground was Wilbur Massey’s Practical Farming (1907), which described how “nature restores a wasted soil” in this way:

The broomsedge grass covers the old field, and the wind bears the light seed of the old field pine, which starts and grows in the sheltering grass. The pine sends a long tap root down into the subsoil below where the little plow of the devastator went, and year after year pumps up material for growth. . . . Year after year it covers the land with its fallen leaves . . . and a forest grows up without any help from man.

This “old field succession” was precisely what a generation of ecologists began studying in the 1950s, helping to transform the discipline of ecology from one concerned with enumerating and describing plant communities to one tracing energy flows through the landscape.11

The post-World War II South was a landscape in transition. C. Vann Woodward famously called it a “Bulldozer Revolution” in 1958, in view of “the roar and groan and dust,” the economic growth and national integration, the “relentless speed” and “heedless methods.” Military bases, nuclear power plants, airports, and tract housing reshaped much of the South. And ecologists were there just in time to chronicle the transition. Eugene P. Odum and Frank Golley, both professors at the University of Georgia in Athens, used the Atomic Energy Commission’s Savannah River Site near Aiken, South Carolina, as a staging ground for their experiments. The place was full of “abandoned” farmlands—though given the origins of the Savannah River Site, one might better call them “dispossessed.” Odum, Golley, and their assistants not only counted and measured flora, as previous generations of ecologists had, they also clipped them, separated the clippings into live and dead material, dried the clippings in an oven, weighed them, ground them into dust, and analyzed their chemical composition. In this way, they sought to calculate the energy present in the landscape during different stages of old field succession, which, as Golley noted, was a more typical landscape than the “climax systems or managed crops” which characterized most previous studies of plant communities. A “great portion of the unmanaged land on earth,” Golley wrote, “is in some developmental state.”12

“Developmental state” was a pretty good description of what Odum and Golley observed from the Georgia Piedmont, for the long-declared “New South” seemed really new this time. The fact that their research was carried out at the Savannah River Site “Cold War Dixie” nuclear installation was emblematic of this transition. They studied the post-agricultural South as it was being made, thanks in good part to federal investment in the southern military-industrial complex.13

Most observers of broomsedge in the South over the last two centuries have been convinced of its uselessness, unless it was as an indicator of poor land and poor management. Even wild animals seem to have little use for Andropogon virginicus. Wildlife management professionals plant species that encourage turkey, quail, and other game animals. In Herbert Stoddard’s landmark “cooperative quail investigation,” which in 1925–1926 analyzed the contents of 302 bobwhite quail stomachs, not one contained a recognizable broomsedge seed. The consensus has long been that the grass “is of relatively little value” except as cover for nesting birds. In 1941, however, Mississippi saw an unusually heavy snow—twelve inches along the road to Jackson—that covered everything except for tall stalks of broomsedge, which held their seed above the surface of the snow. Verne E. Davison and William R. Van Dersal, both with the Soil Conservation Service, happened to be out driving after this snowfall and witnessed “what can only be classed as extensive utilization of broomsedge seeds” by a flock of juncos and song sparrows. “Wherever clumps of broomsedge were to be found near the road,” the scientists wrote, “groups of as many as 10 or 15 birds were busily engaged in stripping the stalks of their seeds. They would fly into the air, perch on or near the tip of the grass culm, bend it to the snow surface by their weight, then extract the seeds and eat them.” After assuring their readers that they were not breaking with orthodoxy and actually recommending the use of broomsedge in wildlife management, Davison and Van Dersal compared the birds’ behavior to that of explorers subsisting on shoe leather. “What are apparently worthless plants may, in times of great stress,” they concluded, “bridge the gap between starvation and survival.”14

We see what we train ourselves to see, and we typically train according to the values and needs of the historical moment. Most birds, it appears, don’t really “see” broomsedge—until there’s a severe snowfall and they can’t find anything else to eat. Wildlife biologists didn’t really see it either, until that snowfall and dramatic junco song sparrow feeding made it legible. Economic interest guides a lot of our seeing. Broomsedge is not compatible with nutritious pastureland or with large numbers of quail that wealthy folks are willing to pay to hunt, and so it is seen as a “worthless” plant that “infests.” Broomsedge is the thing that is burned to make way for the cash crop.

The “Bulldozer Revolution” continues apace in the South and everywhere else. We live in the Anthropocene—an epoch characterized by destructive human dominance—in the midst of the “sixth extinction,” in a “post-wild” world with “the end of nature” already well in the past. To put it in southern terms, we have made the earth into something like an old field in the Virginia Piedmont. We are likely to see a lot more broomsedge. Looking forward, what will we see when we gaze out on those golden fields?15

One answer to that question came to me on a late February day in 2016, the sun in its last horizontal glory before disappearing over the edge of the world. I was with my children at “the powerlines,” a swath of broomsedge, blackberry brambles, and loblolly pine seedlings beneath powerful electric wires not far from our house where my children—like their father twenty-five years earlier—like to play hide and seek. It was time to go home. I stood up and my eight-year-old daughter, followed by the others, came charging down the hill, the slanted sunlight full on her lean frame, pink snow boots, green striped leggings, ochre floral shirt, pigtails. In her hands was a bundle of broomsedge—long yellow wisps from last year’s efflorescence attached to roots and tender green shoots. “We want to plant them in our meadow,” my son explained, close on her heels. He meant a sandy area in our yard, about fifty square feet, with a few large sandstones and some struggling creeping phlox. Broomsedge in our yard. In this old cotton-mill, piedmont railroad town of Kennesaw, now transformed into a universe of bedrooms for Atlanta, a residential hinterland of the urban New South. Broomsedge for the meadow. Broomsedge for the approximation of wild prairie. Broomsedge for beauty. Broomsedge intended. Amber waves.

William Thomas Okie is an associate professor at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, associate editor of the journal Agricultural History, and the author of The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture and Environment in the American South (Cambridge University Press, 2016). He is at work on a book provisionally titled “Old Fields: A History of the American South in Six Ordinary Plants.”

- David Foster Wallace, “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” Review of Contemporary Fiction 13, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 183. Or as Paul S. Sutter put it, “Irony may be a compelling way of presenting” problems, “but it is analytically limiting when it comes to resolving” them. See Paul S. Sutter, Let Us Now Praise Famous Gullies: Providence Canyon and the Soils of the South, Environmental History and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 8.

- A. S. Hitchcock, Manual of the Grasses of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935), 28, 738–39.

- On agricultural reform in the nineteenth-century South, see Steven Stoll, Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002); Lynn A. Nelson, Pharsalia: An Environmental Biography of a Southern Plantation, 1780–1880, Environmental History and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007); Jack Temple Kirby, Poquosin: A Study of Rural Landscape and Society, Studies in Rural Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Drew A. Swanson, A Golden Weed: Tobacco and Environment in the Piedmont South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014); and William Thomas Okie, The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South, Cambridge Studies on the American South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016). On the effect of emancipation, see Erin Stewart Mauldin, Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). On the creation of antebellum southern tradition in the twentieth century, see David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001); Karen L. Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Kirby, Mockingbird Song: Ecological Landscapes of the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006); and Nina Silber, The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865–1900, Civil War America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

- Charles Fisher, address to the Rowan Agricultural Society, July 4, 1821, Salisbury, NC, in The American Farmer (Baltimore) 3, no. 22 (August1821): 169; A. W. Venable, letter to the editor, Farmers’ Register, February 1, 1838; Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, with Remarks on Their Economy (Mason Brothers: New York, 1861), 65; and Book Farmer, “Rotation of Crops,” Southern Farm and Home 3, no. 5 (March 1872): 172.

- See, for instance, its relatively high profile in William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), especially 213; as well as Annick Smith, Big Bluestem: A Journey into the Tallgrass (Tulsa, OK: Council Oak Books, 1996). See, for instance, the conversation between Milton Cayce, “Broomsedge,” Southern Planter 53, no. 6 (June 1892): 332; and W. F. Massey, “The New Pasture Grass,” Southern Planter 53, no. 7 (July 1892): 390; William L. Bradbury, “Facts Drawn from Experience and Broomsedge,” Southern Planter 54, no. 2 (February 1893): 68; and Massey, “Scrub-Hay,” Southern Planter 53, no. 6 (June 1892): 335.

- E. J. Peters and S. A. Lowance, “Fertility and Management Treatments to Control Broomsedge in Pastures,” Weed Science 22, no. 3 (May 1974): 201–205; L. R. Neel, Control of Broom Sedge, Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station Circular 57 (1936).

- Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow, Barren Ground (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1925), 3, 4.

- Glasgow, 115.

- Glasgow, 146, 274.

- Erskine Caldwell, Tobacco Road (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1932), 2, 172, 16, 22, 119.

- Wilbur Fisk Massey, Practical Farming: A Plain Book on Treatment of the Soil and Crop Production (New York: Outing, 1907), 19, 20. See Donald Worster, Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 306–11; Joel Bartholemew Hagen, An Entangled Bank: The Origins of Ecosystem Ecology (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 107–11; and Frank B. Golley, “Structure and Function of an Old-Field Broomsedge Community,” Ecological Monographs 35, no. 1 (January 1965): 113–37.

- C. Vann Woodward, “The Search for Southern Identity,” Virginia Quarterly Review 34, no. 3 (1958): 323–24; On SRS and similar sites, see Kari Frederickson, Cold War Dixie: Militarization and Modernization in the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013); Louise Cassels, The Unexpected Exodus: How the Cold War Displaced One Southern Town (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007); Ecology and Management of a Forested Landscape: Fifty Years on the Savannah River Site, eds. John C. Kilgo and John I. Blake (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005); Caroline Rose Peyton, “Radioactive Dixie: A History of Nuclear Power and Nuclear Waste in the American South, 1950–1990” (PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 2016); and Golley, 113.

- Andrew C. Baker has recently chronicled this transition, focusing on the outskirts of Washington, DC and Houston, Texas, in Bulldozer Revolutions: A Rural History of the Metropolitan South, Environmental History and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018).

- Herbert L. Stoddard, Report on Cooperative Quail Investigation, 1925–1926, with Preliminary Recommendations for the Development of Quail Preserves, (Washington, DC: Committee Representing the Quail Study Fund for Southern Georgia and Northern Florida in Cooperation with the US Biological Survey, 1926), 16. For more on Stoddard and his ecological field work, see Albert G. Way, Conserving Southern Longleaf: Herbert Stoddard and the Rise of Ecological Land Management (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011); Verne E. Davison and William R. Van Dersal, “Broomsedge as a Food for Wildlife,” Journal of Wildlife Management 5, no. 2 (April 1941): 180, 181. See also “Broomsedge Bluestem Plant Guide,” prepared by Selena Dawn Newman and Maraya Gates (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006), https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_anvi2.pdf; “Broomsedge Bluestem Andropogon Virginicus L. Plant Fact Sheet,” prepared by Melinda Brakie (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, September 2009), https://plants.usda.gov/factsheet/pdf/fs_anvi2.pdf; and Davison and Van Dersal, 180, 181.

- Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Henry Holt, 2014); Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013); and Bill McKibben, The End of Nature, Trade Paperback Edition (New York: Random House, 2006). On the Anthropocene concept, see for starters W. John Kress and Jeffrey K. Stine, eds., Living in the Anthropocene: Earth in the Age of Humans (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2017); Jeremy Davies, The Birth of the Anthropocene (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016); and Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero, and Robert Emmett, eds., Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).