In the autumn of 1938 a photographer named Charles A. Farrell visited a seasonal mullet fishing camp at Brown’s Island, in Onslow County, North Carolina. What he discovered there captured his imagination: a remote hamlet of fishermen’s shanties far from civilization and two legendary clans of fishermen in relentless pursuit of one of the Atlantic’s great schooling fishes, striped mullet, known on those shores as “jumping mullets.”

Neither of the two clans, the Gillikins or Lawrences, came from the mainland nearest the island. Instead, they traveled by boat there in the fall of the year from Otway, a small farming and fishing community forty miles to the east, in a section of the neighboring county, Carteret, that locals call “Down East.” Year after year for generations, the men left their homes in Otway and returned to Brown’s Island and the sea.

Farrell’s photographs provide a unique portrait of mullet camp life and an invaluable historical record of one of the largest commercial fisheries in the American South. Indeed, for much of the nineteenth century, the mullet trade on the North Carolina coast comprised the largest saltwater fishery in the South.1 Even as late as the 1930s, large numbers of fishermen still moved to the barrier islands every autumn to work out of camps like the one at Brown’s Island. From Ocracoke Inlet to Cape Fear, their camps lined the shores. Centered at Morehead City, N.C., fish dealers loaded so many barrels of salt mullet on outbound freight cars that local people referred to the railroad as “the Old Mullet Line.”

Fish dealers loaded so many barrels of salt mullet on outbound freight cars that local people referred to the railroad as ‘the Old Mullet Line.’

During the late 1930s, Farrell documented fishermen’s lives in a large swath of the North Carolina coast, as well as at Brown’s Island. The proprietor, along with his wife, of an art supply store and photography studio in Greensboro, in the state’s Piedmont, Farrell had long had a special interest in the lives of commercial fishermen.2 He had been taking photographs in coastal communities for some time when, in 1938, he approached W. T. Couch at the University of North Carolina Press about publishing a book of the photographs. Couch had previously hired Farrell to take photographs for several other books. They signed a contract for Farrell’s coastal book later that year.3 Farrell completed the photographic portion of the book, but apparently made little headway with the text.4 Now preserved at the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh, his photographs are one of the fullest documentary accounts of southern fisheries at any time in the twentieth century.5 The following is a selection of Farrell’s photographs of the mullet fishermen at Brown’s Island, with extended commentary.6

All photographs courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

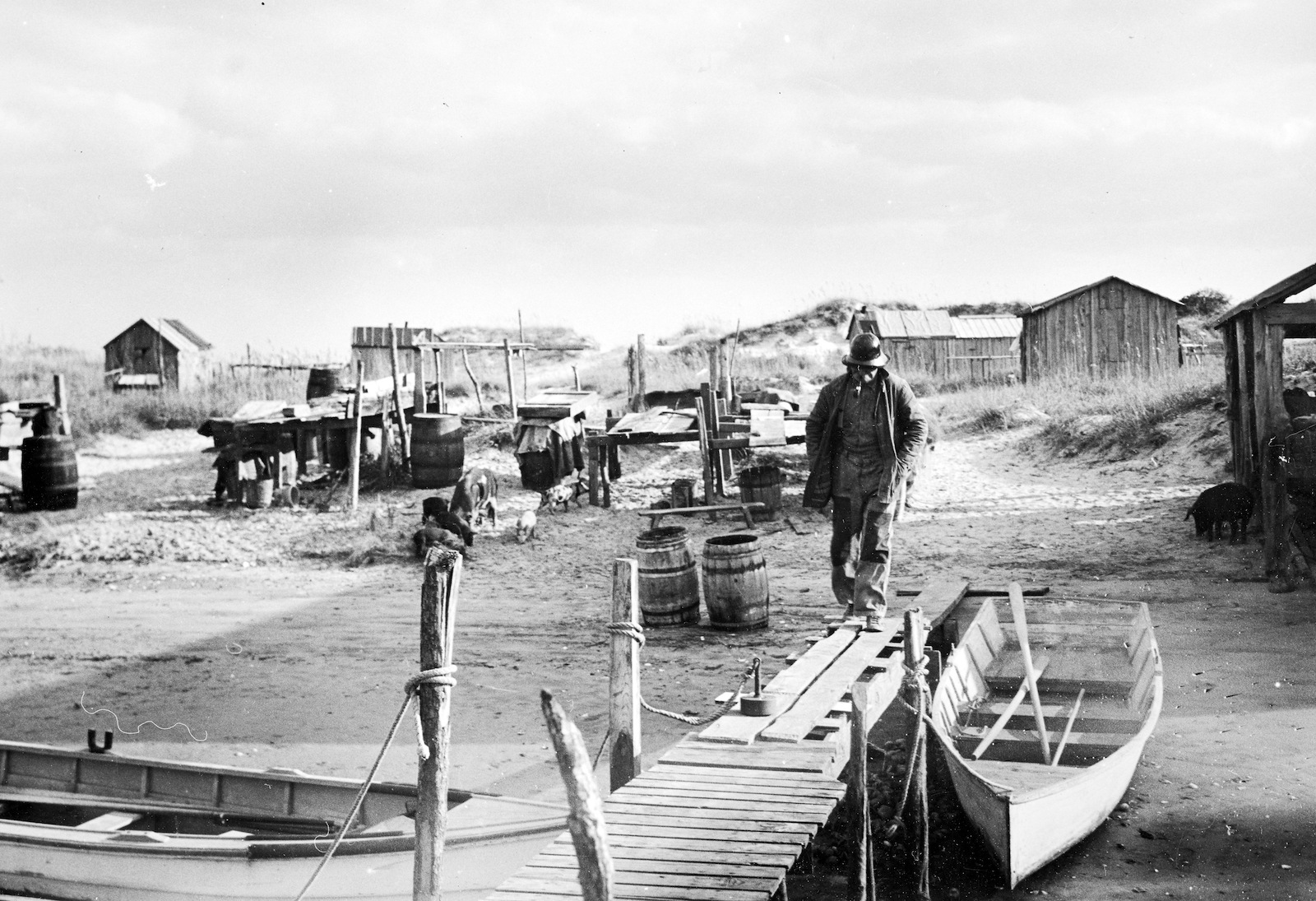

An early morning view of the mullet camp at low tide from a dock on the sound side of Brown’s Island. One of the oldest mullet fishermen, Bedford Lawrence, walks down the dock in a farmer’s coat and “sou’wester.” A clinker-built boat is tied by its anchor line to a post on the left side of the dock, a flat-bottomed skiff on the other side. A sizable portion of the camp can be seen behind Lawrence: wooden tables for cleaning the fish; salting trays; empty barrels and kegs for packing salt fish; and a few of the fishermen’s cabins. An open shed for storing gear and barrelfuls of salt mullet stands on the far right. Two of the camp’s hogs, a pair of cats, and a goat are finishing off leftovers from the fish cleaning tables, while another hog has found something interesting next to the shed. Roughly four miles long, with an ocean beach facing southeast, the island was only a few hundred yards wide next to the inlet, where the camp was built: the ocean beach lay just beyond the high dunes in the distance.

A view of the mullet camp from the ocean dunes facing the sound side of the island. Piles of fire-wood, a wandering hog, and several fishermen, including one tending to his laundry, can be seen around the camp. The bunkhouses and the cook shop, near left, have doors and windows open to the breeze. With no screens, the fishermen relied on sea winds to keep cool and to discourage the swarms of mosquitoes, files, and yellow jackets that plagued the island until the first hard frost. For other reasons, too, a barrier island was not an easy place to live. Sun-baked, arid, and wind-swept, the long, narrow islands resembled a desert from an ecological point of view. Most were uninhabited, and only special breeds of plants, animals, or men succeeded in making homes on them.

At least four other cabins and a larger dwelling made up the camp as well, but cannot be seen from this angle. In the distance, a maritime forest occupied the south end of the island, then a broad salt marsh, and the mainland on the horizon. A stretch of open sound water can be seen on the far right, beyond the shed. The straight, narrow passage through the salt marsh is part of the Intracoastal Waterway, the “Big Ditch,” dredged in the 1910s and ’20s to provide a sheltered path for commercial vessels to transport goods the entire length of the Eastern Seaboard.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

Leonard Gillikin posing with pipe on the ocean beach. He is leaning on a tripod, presumably one that Charles Farrell used to support his camera. Though a relatively young man—he was born in 1913—Gillikin was the boss of the mullet gang at Brown’s Island. He is wearing a cloth fedora at a rakish angle and a coat of the kind of herringbone twill that was issued to laborers in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), one of the Roosevelt administration’s work programs for unemployed and underemployed men. The Federal census indeed lists him as a (CCC) road worker, though no doubt he also farmed and fished back home in Otway. You can see the sun on his hands and face. Behind him an axle for an automobile or light truck rests on the beach, perhaps intended for conversion into a cart. In the distance, the camp’s hogs are grazing among the sea oats. At Brown’s Island, as at all of the state’s mullet camps, the fishermen worked on shares, not for wages; the captain typically earned an extra half-or full share, as did the owners of the boats and seine.

Bedford Lawrence on the ocean beach at Brown’s Island. He is wearing a faded denim jacket, a gabardine or denim shirt, and an oilcloth or rubberized canvas sou’wester. He may have waterproofed the hat with linseed or cottonseed oil. In one hand he holds an oyster knife or a net needle; in the other, his pipe, filled, no doubt, with the R.J.R. tobacco that his grandchildren told me was his habitual brand. From the look of the surf, a good blow is coming on, probably out of the northeast.

Then seventy years old, Bedford Lawrence had been mullet fishing at Brown’s Island every autumn since the 1880s. Like all the fishermen, he came from Otway, a remote community on the salt marshes of Ward’s Creek, a two-day trip by boat. At home he worshiped at the North River Primitive Baptist Church, played fiddle at community square dances, and was head of a large family. Like all the fishermen, he was not a wealthy man. He and his wife Emma, five children, and often other relatives all lived in a two-room house that did not look that much sounder than the cabins at Brown’s Island, at least in the memory of his descendants. No wonder he enjoyed the island’s peace and quiet.

Like all the fishermen, he came from Otway, a remote community on the salt marshes of Ward’s Creek, a two-day trip by boat.

Bedford Lawrence was a “saltwater farmer”: he made his living partly on the water and partly on the farm. That was true of most Otway residents and was also typical of mullet fishermen throughout the North Carolina coast. Otway was located on salt marshes, but mullet fishermen at many other camps traveled from farming communities far from the sea and, except for mullet fishing, kept to their farms.

Bedford Lawrence lived at the Brown’s Island camp beginning with the “mullet blow”—a gale, usually in late August or early September, that announced the shift of prevailing winds to the northeast and the arrival of the jumping mullet. He stayed at Brown’s Island all fall and came home sometime before Christmas. The rest of the year, he divided his time between fishing, clamming, and oystering closer to home and also tended five acres of field and garden. He grew two acres of sweet potatoes, an acre of “Irish” potatoes, and feed crops for his cows, horses, and hogs.

Bedford Lawrence’s grandson, a dredge boatman named H. B. Lawrence, told me that his granddaddy didn’t mind getting away from Otway during the sweet potato harvest. Digging and banking sweet potatoes—“banking” involved covering piles of them with salt marsh rushes and pine straw in order to preserve them through the winter—was hard work, but so was mullet fishing, and he could leave the harvest in the hands of his wife and children back home. “I have been told that Bedford probably made between $1,000 and $1,200 a year, between farming and fishing,” his grandson said. “We didn’t have a lot of money, but we always had plenty to eat and we never went hungry.”

Every autumn Bedford Lawrence returned to the island for the mullet fishing, along with other members of the Lawrence and Gillikin clans. In his younger days, he seems to have been captain of the Brown’s Island crew—in his notes, Charles Farrell referred to him as “old Captain Lawrence.” By the 1930s, however, he was the mullet camp’s lookout. No job was more essential to a mullet fishery’s success. The fish moved down the beach from the north in great schools, and a keen, practiced eye, as H. B. Lawrence told me, “could see the difference in the color of the water.” His granddaddy, he recalled, “had an eye for mullet.” He waited for the fish from a post roughly half a mile north of the camp. When he spied a school of mullet, he gave a shout and raised a flag (usually just a wax myrtle or yaupon branch), spurring a frantic rush of his comrades to their boat and into the waves.

His granddaddy, he recalled, “had an eye for mullet.”

Briant Gillikin leaning on a mullet boat by a dune on the ocean side of Brown’s Island. A cotton seine, with the warp folded on top, rests in the stern, so that the boat is ready for launching at the lookout’s cry of “Bo-at, bo-at, bo-at!” The old fisherman is wearing worn denim trousers, blanched by exposure to sun and saltwater, and a fedora. A long wooden beam, one of two used to carry the boat into the surf, rests at his feet.

Behind the boat are net spreads, typically made of ash, with a smaller net, probably a gill net for spot fishing, draped over the spread on the far left. The fishermen doused their cotton nets with lime every day to discourage rot from saltwater and sun exposure, but with the same purpose in mind also dried them on the net spreads on down days. The fishermen’s nets may have been knit by hand in Otway or may have been factory made; the late 1930s was just at the cusp of a widespread change from handmade to factory-made fishing nets in the mullet fishery. If handmade, the seine had been knit, Henry Frost, an eighty-year-old mullet fisherman at Bogue Banks, told me, by “the mothers and grandmothers in their homes in the wintertime.”

The mullet boat on which Briant Gillikin is leaning is clinker (lapstreak)-built, made of local juniper, double-ended (pointed at bow and stern), and roughly 26 feet in length. She is lightly built, but strong: designed to be light enough for a crew of men to pick up and move quickly down the beach and into the surf, but strong enough to crash through breaking waves and carry a 350 to 450-yard-long seine and a crew of five or six men.

The mullet boat on which Briant Gillikin is leaning is clinker.

Watermen had long used boats of similar design and construction when they needed to work on the ocean side of North Carolina’s barrier islands. As early as the eighteenth century, they used them as pilot boats, carrying local pilots to seagoing vessels waiting offshore. Fishermen later used such boats for whaling on Shackleford Banks, a barrier island to the east, and for dolphin hunting between Hatteras Island and Bogue Banks. Similarly, U.S. Lifesaving Service and U.S. Coast Guard crews used boats of this design to reach shipwreck victims in the surf.

Though professional boatbuilding shops in New England built boats of this kind in large numbers, a slight casualness of construction betrays that this boat was local-built, probably in a fisherman’s backyard in or around Otway. Note the varying widths of the planking, particularly low and forward. When asked to evaluate this boat’s seaworthiness, Mike Alford, the retired curator of traditional workboats at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, N.C., stressed nonetheless that the boat was a well-built and highly functional craft. She was as sturdy and handy as the finest of the U.S. Coast Guard’s boats, he said, just not made to look as pretty.

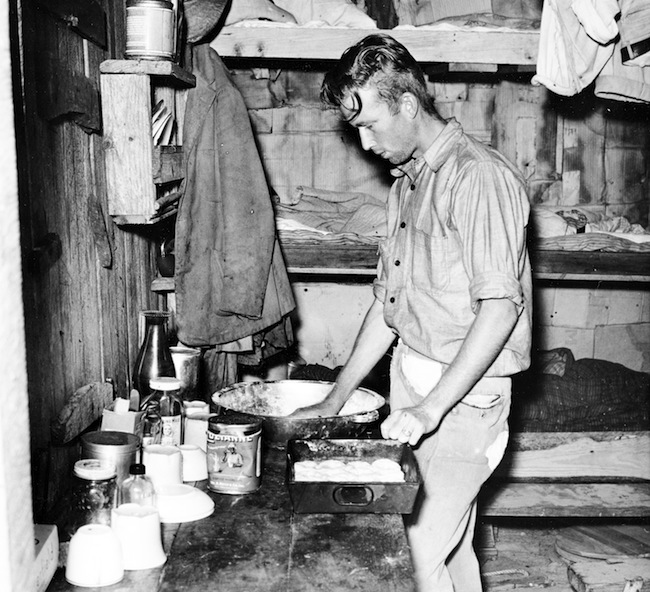

Buck Gillikin, cook. Young Gillikin is making biscuits in a one-room cabin that served both as a kitchen and one of half-a-dozen bunkhouses. He has nearly filled a galvanized steel pan with biscuits and will soon place them in the oven. A tin of baking powder sits next to his mixing bowl, in front of containers of other cooking ingredients, including what looks like a jar of pickles or peppers. “When a boat doesn’t come from the mainland,” Charles Farrell wrote on the back of the print, “Buck may have nothing to serve but flour biscuits and black strap molasses.”

When a boat doesn’t come from the mainland, Buck may have nothing to serve but flour biscuits and black strap molasses.

On this day, Buck is frying corned spots for the mullet fishermen, which he will serve with the biscuits and molasses. While cooking was his main job, he also had duties that took him out of the kitchen, much as cooks on sailing ships did at sea. Other photographs in Farrell’s collection show him helping to launch a mullet boat into the surf. In this photograph, his coat hanging on the shelf has a worn place on the left sleeve that betrays wear either from the wooden beams used to carry the mullet boat or perhaps from the warps, the two heavy ropes that the fishermen used to haul the seine and fish ashore. At such times, the crew captain needed every hand on the beach.

A mullet camp was a man’s world, at least at Brown’s Island, and making biscuits was hardly the fishermen’s only domestic duty that would have been women’s work back in Otway. Again, much like sailors at sea, the fishermen scrubbed floors, washed laundry, mended clothes, and did whatever else necessary to keep the camp tolerably livable.

A Sunday visitor. The nearest villages to the mullet camp both lay approximately 12 miles west at the mouth of the New River, a long haul anyway you made it in that day. “Yet,” Charles Farrell noted, “most Sundays the girls arrive.” A copy of this photograph in a family collection at Otway identifies this young fan of Mickey Mouse as Elizabeth Tuslee or Tuskee of Jacksonville, a small town well up the New River that was the seat of Onslow County. “Every fisherman on the island wanted his picture made with this charming lass,” Farrell wrote on the back of the original print.

Most Sundays the girls arrive.

How often the fishermen visited the mainland of Onslow County, where they might have first met Miss Elizabeth, is not clear. Chadwick’s Landing, one of the two villages at the mouth of the New River, did have a pair of general stores where the fishermen might have gone to procure groceries and tobacco, and Marines, a small community on the other side of the river, had a gristmill. Stump liquor was not in short supply at either place.

Behind the young lady, salted spots hang on nails in a cabin wall. The fishermen headed, split, gutted, and lightly salted the fish, then hung them to dry in the sun and wind: it was an ancient and much favored way to preserve fish without having to salt them so heavily as when they packed them in brine. Buck Gillikin, the camp’s young cook, intended to fry these fish sometime soon.

Salt fish drying in the sun was once a common sight on the North Carolina coast, prior to the ready availability of ice and refrigeration. Fishermen’s families often laid the fish on the roofs or porches of their houses, at other times on makeshift benches in a sunny, unused room, or, as here, pinned to the sides of homes or outbuildings. At Salter Path, Norwood Frost told me that his mother-in-law used to hang salt fish from her clothesline.

The Gillikins and Lawrences carrying their surfboat, loaded with the mullet seine, to its resting place above the high tide line. Two rows of fishermen lifted the boat, holding strong beams across their shoulders fore and aft, secured to the boat by a pair of heavy lines that ran stem to stern. Another half-dozen men held long oars secured to the boat at the thwarts, but could not have been bearing much weight on them. Bedford Lawrence holds one end of an oar on the far side of the boat, while his grandson, Tildon Lawrence, holds the opposite end of the oar in front of him. Net spreads stand just beyond them, a pooch in front. They seem to be two men short, judging by the unmanned oar. This was a demonstration, presumably done for Charles Farrell’s benefit.

Norwood Frost, Henry Frost, and Norwood’s son Rodney, of Salter Path, N.C., are members of the last two crews of mullet fishermen in North Carolina that still fish fundamentally the same way as the Gillikins and Lawrences did at Brown’s Island in the 1930s. Norwood, still the captain of one of the crews, is now eighty years old; his brother is seventy. When they looked at this photograph with me recently, they described how the fishermen handled the boat and seine in the water, based on a lifetime of fishing for mullets on Bogue Banks, which is just east of Brown’s Island, and on what their grandfather, who was also captain of a local mullet crew, told them about mullet fishing in his younger days. When Henry and Norwood Frost were young, Bogue Banks was home to ten to twelve mullet camps.

On a mullet-fishing day, the Frosts told me, the fishermen carried their boat down the beach and into the surf for the first haul of the day before sunrise. As they entered the surf, the boat’s crew jumped aboard, while other hands strode into the water as deep as they could go to hold her steady in the breakers. Standing on the ocean’s edge, another fisherman held fast to a five or six-foot-long post called a “suds staff,” to which was attached one end of the seine. The suds staff kept that end of the seine fixed on shore, while the boatmen rowed through the surf and the net man, in the rear of the boat, gradually let out the seine in an arc around the school of mullet—“striking mullet,” it was called.

According to the Frosts, the fishermen then rowed ashore and secured the other end of the seine to a second suds staff, so that the seine made something of a half-circle in the ocean, with both ends rooted on the beach. After dragging the boat ashore, every fisherman in the camp then took hold of one of the two warps, which were also attached by bridles to the suds staffs, and hauled the seine onto the beach by hand, heavy work with a big catch. For decades, the mullet fishermen at Salter Path have used tractors to haul in their seines.

Now hemmed in by beach house owners, fishing pier operators, and sunbathing tourists, many of whom consider them to be infringing on their property rights and leisure time, the Frosts and their crews have not given up mullet fishing on the ocean beaches at Bogue Banks. They still take to the beach every autumn in pursuit of jumpin’ mullet, and it’s a sight to see.

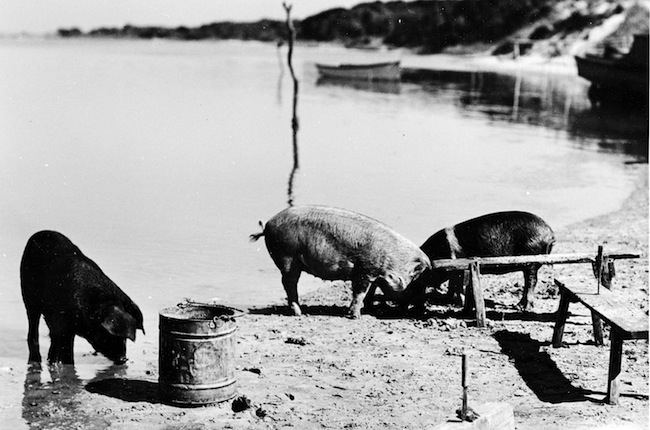

A trio of hogs cleaning up after a fishermen’s oyster or clam dinner on the sound side of the island. The fishermen left a pair of oyster knives stuck in the benches. The white belted animal on the right is a Hampshire, while the other two are mixed breeds. Hampshires are one of the oldest hog breeds in the United States, popular for their easy temperaments, hardiness, and foraging ability, all of which suited them well to life on Brown’s Island.

The Gillikins and Lawrences brought a small menagerie with them from Otway: cats for the mice and rats, a dog to scare away raccoons, snakes, and the occasional bear, and the hogs and a goat to scavenge the great piles of fish guts and other offal left over from cleaning their catch. The fishermen occasionally slaughtered their hogs at the end of the season, but most of the men found the pork too redolent of fish because of the hogs’ diet and instead carried them back home to Otway.

The autumn winds continue to awaken a fierce yearning for the seashore and for a taste of jumping mullet, either fried, stewed or, best of all, roasted slowly over hot coals until golden brown.

The days of hogs grazing on Brown’s Island were numbered. So was the future of the Gillikins and Lawrences on the island. Three years after Charles Farrell’s visit, at the outset of the Second World War, the War Department confiscated the island for use as a bombing range. Brown’s Island has been part of the Camp Lejeune Marine Corps base and off-limits to fishermen ever since. The state’s other mullet camps did not last much longer. Few, if any, survived hurricane Hazel in 1954. Back home, the “mullet blow” still stirs spirits and lift hearts, however. Albeit on a smaller scale, fishermen still pursue jumping mullet, even if they no longer live in camps and often must work in the shadow of high-rise motels. For many of us who grew up on the North Carolina coast, the autumn winds continue to awaken a fierce yearning for the seashore and for a taste of jumping mullet, either fried, stewed or, best of all, roasted slowly over hot coals until golden brown.

Historian David S. Cecelski is the author of several award-winning books and hundreds of articles about the history and culture of the North Carolina coast, including The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina and, most recently, The Fire of Freedom: Abraham Galloway and the Slave’s Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

For their research assistance and technical advice, I would like to thank Mike Alford, Larry Babits, Paula Johnson, Ellen Cloud, Dennis Chadwick, Michael Fulcher, Sonny and Ginny Williamson, Karen Amspacher, Pam Morris, Joel Hancock, Glenn Gordinier, Ryan Walker, Alison Walker, Kim Andersen, Lisa Whitman- Grice, Patricia Hughey, Richard Searles, Matthew Turi, Elise Allison, and Roger Farrell. In addition, I would like to extend a special word of thanks to Rodney, Norwood, and Henry Frost for discussing the photographs with me at Salter Path, and to all the descendants of the Brown’s Island mullet fishermen who gathered at the community supper on Harkers Island on the 14th of May, 2013, but most especially Mr. H. B. Lawrence.

NOTES

- For historical background on the mullet fishery on the North Carolina coast and for references to other sources, see David S. Cecelski, “The Hidden World of Mullet Camps: African-American Architecture on the North Carolina Coast,” North Carolina Historical Review 70, no. 1 (January 1993): 1–13; and David S. Cecelski, The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 77–78, 209–211, 248–249.

- For more on Charles A. Farrell (1893–1977), see Farrell Family Papers, Greensboro Historical Museum Archives, Greensboro, N.C.

- W. T. Couch to Charles Farrell, February 11, 1938, April 25, 1938, and May 3, 1938, Tobe, 1938 file, Charles Farrell Collection, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, Chapel Hill, N.C.

- Farrell to Couch, June 3, 1939, Sub- group 4: Author/title Publication Records, University of North Carolina Press Records, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, Chapel Hill, N.C.

- Charles A. Farrell Papers, North Carolina State Archives, North Carolina Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C. For copies of some of Farrell’s Brown’s Island photographs that in some cases include unique annotations, see the Sarah Lee Brock Collection, Onslow County Museum, Richlands, N.C.

- Reminiscences, Folder 2, Group 2: Charles Farrell Series, Farrell Family Papers, Greensboro Historical Museum Archives.