Drive through any town, anywhere, and among the essential food stores and gas stations there are repair shops. “There will always be a need for somebody to repair broken stuff,” said ceramics restorer Lenore Guston. “Because we’re humans, we’re breaking stuff all the time.” Over the last year and a half, with the support of an Archie Green Fellowship from the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, we set out to discover the current state of repair industries in North Carolina. Often, when something is fixed, the repair itself is invisible—the chip is polished away, the paint perfectly matched. We wanted to know about the stewards of our belongings, the folks who know how to reverse our mistakes and erase the imprint of time passing. This set of twenty interviews, conducted between September 2020 and July 2021, opens the workshop door and steps behind the customer counter to reveal the artistry, satisfaction, and expressions of care behind repair.

Our collaboration and interest in this project grew out of our shared refusal of throwaway consumer culture and admiration of traditional craft methods. We met in 2016 at The Scrap Exchange, a creative reuse center in Durham, North Carolina, that diverts tons of waste from the landfill by accepting, sorting, and reselling. Julia is a sculptor whose work explores how our cultural relationship to material objects has changed since the rise of global manufacturing. In 2019, she launched the Radical Repair Workshop in a revamped vintage camper trailer. This gallery-meets-workshop is a mobile public art project that teaches simple repair skills and invites the public to donate their broken objects. “The goal, despite having the word repair in the title, is not necessarily to bring things back to their working order,” Julia told me when I interviewed her about the project in January 2020. “It’s designed to explore how sentimental objects can turn towards sculpture.” Today, when it is often cheaper to replace an item than to fix it, specialty skills and loving care for belongings work together to resist the waste of capitalism. And, it turns out, it’s an immensely satisfying way to earn a living, though it is challenging and sometimes lonely.

Any nostalgia or romantic ideals we may have had before our fieldwork began were quickly wiped away, hastened by the challenges posed by the pandemic. As a folklorist, I am trained to have meaningful conversations across divides, but our face masks and outdoor interview protocols made political differences newly visible—and sometimes insurmountable. (There were candidates we could not include because of their lack of COVID-19 precautions.) Despite the difficulties of cold-calling and setting up visits, meeting these generous strangers, and digging around their envy-inducing workshops, was an unexpected pandemic lifeline for both of us.

Call it naivety, but Julia and I did not expect that it would be challenging to find interview candidates who were not white men over fifty. Many of these “handymen” fell into their fields during the Vietnam War era, often by chance, but found enough success to develop and sustain a niche business. Repair work is difficult—the pay is usually only enough to get by, store owners can be wary of training staff (who may one day become the competition), and it can be hard to find community, especially if you are a woman or a person of color. We made special effort to include voices from many backgrounds in this collection, but readily acknowledge their absences.

We also could not have predicted the wider relevance the subject of repair would hold for our country in 2020 and 2021. Among so many other things, the pandemic exposed our need to be more self-reliant, and laid bare how much about our country needs fixing. President Biden’s campaign slogan “Build Back Better” addressed this brokenness. In response to the murder of George Floyd, spiritual leaders called upon the Japanese tradition of kintsugi (piecing together fractured ceramics with gold lacquer), in which the act of fixing, of transformation, is made visible and beautiful, as an apt metaphor for repairing our broken social systems. In July 2021, President Biden issued the “Right to Repair” executive order, which requires manufacturers of electronics—from farm equipment to laptops—to offer replacement parts and instruction manuals that will empower more individuals and local shops to repair. A $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill passed in August includes funding to repair our aging bridges and roads—but there’s a shortage of skilled laborers ready for the work. This moment calls for repair.

When considered together, the twenty interviews we share here reveal four themes relevant to the broader repair industry. An horologist, two furniture restorers, and a luthier taught us about the apprenticeship model—its strengths in delivering highly-specialized skills and its challenges. A historic window restorer, auto bodywork expert, typewriter repairer, and boat-building fix-it-man exposed tensions between adapting to new modes of manufacturing and preserving quality. A cobbler, a father-son diesel boat engine mechanic team, a third-generation plasterer, and a chair-caning minister revealed how often specialty trades are passed down family lines. Nearly everyone we spoke to emphasized their inherent knack for their craft. We share the experiences of two women who restore historic windows and two ceramics repair specialists—none of whom ever thought they would fix things for a living—that give insight to this natural aptitude. Finally, a wind instrument repairer, an auto and tire service shop owner, another diesel mechanic, and a ceramic restorer help us understand the joy, pride, and satisfaction of the labor of repair. Mending and maintaining objects is ultimately an act and expression of care—for the thing itself, for the customer, for the environment—and for “the old ways,” as chair caner Randy Winn said.

The work of fixing is straightforwardly satisfying and immediately rewarding in a way that is absent from many kinds of labor today. Several interviewees described the joy of working with one’s hands, bringing specialist skill to a task, and feeling the gratitude and respect of customers. As cobbler Stephen Cash put it, even the unhandy among us intuitively knows the feeling of undeniable accomplishment doing laundry gives—akin to the “instant gratification” of repair. Jared Huffman, the new owner of Y & J Furniture Company Inc., explains: “Maybe one day Elon Musk will come up with a robot that can do this. But for now, I think it’s hands-on and takes time.”

We are hopeful that this collection of voices will help showcase important niche careers and honor the (often) invisible artisanship of repair professionals. There is a fear that without family ties or exposure through education and community, young people—from all backgrounds—may never know how much they could enjoy, or be good at, skilled handwork. Working with your hands to fix, or to create from new, can offer an antidote to the increasing abstraction of office work or the demanding service industry, provide straightforward satisfaction, and engender pride and respect. As Dave Hoggard of Double Hung Historic Window Restoration says, “There are twenty-eight thousand plumbers and one of me.”

David Hoggard

b. 1955, Hodgeville, Kentucky. Historic window restoration, owner and founder, Double Hung Historic Window Restoration, Greensboro.

In general, we’ve become throwaway. When I grew up, I took phonographs apart—phonographs, not record players—to see what made them run. You could fix things, or you would try to fix stuff. People don’t do that anymore. Now it’s, “Let’s just throw it out, start over.”.

They call them replacement windows because you have to keep replacing them.

Older windows are very much repairable. Newer windows are not. There’s a couple of sayings in the industry: “They call them replacement windows because you have to keep replacing them.” They will last fifteen years, then you throw them away and start over again. Whereas your original windows could go two, three, four hundred years. The other saying is: “You call them ‘maintenance free’ because you cannot fix them.” And since “the greenest building is the one that’s already built,” the greenest window is the one that’s already built also.

Windows are kind of the eyes of the house. You change that, you change everything. I notice old windows like most guys notice pretty girls. People view their world through that piece of glass, so we anguish over glass. I really like what we do, to me it is important work. We’re doing work that will last.

Lori Kepko

(right) b. 1982, Clear Lake, Texas. Shop manager, Double Hung Historic Window Restoration, Greensboro.

I think it’s in my blood. It’s really weird. I kind of took to glass like it was just meant for me. I’d never cut a piece of glass before I started working here. As soon as I started doing it, I just loved it. I love the sound that it makes. I like the way it feels in my hand. I like being able to look at it and think about who else was looking through this glass at one point in time and what was going on in their lives and what did they see out of these windows. I feel like there is a lot of history in the glass itself.

Holli Butler

(left) b. 1996, Durham, North Carolina. Window restorer, Double Hung Historic Window Restoration, Greensboro.

I never paid attention to windows until this job and now I’m obsessed. I love glass. Now I can’t drive down the road without having a wreck! If someone else is driving that’s all I’m doing—checking out windows going down the road.

I love to have a goal in mind of what I need to get done. I don’t really mind what I’m doing, they can put me on glass and glazing, repairs, abating, I really don’t care. My favorite is, “Holli, here’s a cart of twenty windows, I need all of these repaired in three days.” A pinpoint goal to reach. I’ll get them all on the rack, make sure everything is done, I can go home and rest. When I wake up, I’m like, “Good, I know what I’m doing.”

Jerry Cheek

b. 1945, North Carolina. Typewriter repair, Midstate Business Machines, Durham.

I have had a lot of good opportunities because of the typewriter.

I was servicing typewriters for Royal Typewriter Company in Washington, DC, in 1968. At that point in time, you didn’t walk into an office without a typewriter being there. And typewriters were the bread-and-butter of what was going on, as far as office machines were concerned. We had the opportunity to go into some government buildings I would have never been in—senators’ offices, congressmen’s offices—because they had typewriters. The typewriter is probably the most universal machine that we serviced. I have had a lot of good opportunities because of the typewriter.

I opened Midstate Business Machines in 1979, and it’s an ongoing company. We took on the MS-DOS machine [one of the earliest personal computers], and I recognized right away that it was not going to do good. The majority of the customers thought we were going to teach them to be a computer operator—you don’t just take the machine and sit it down and say, “OK, here’s your on-and-off switch.” No, you had to stay on the phone, and you had to do it over and over. I said, “This is not what I had in mind.” I decided, instead of the computer, I’m going to put my emphasis on everything but. We deal with a lot of different machines: addressograph machines, cash registers, paper shredders. There’s a lot of machines out there besides the computer.

Anita Hackett

b. 1966, Baltimore, Maryland. Diesel engine mechanic, Chapel Hill Transit, Chapel Hill.

I love my job. It’s not a job to me; it’s like being on a playground. Every day I get to play with my toys and my tools. I love it, just fixing things. And it’s a wonderful feeling to see something out on the road and say, “I fixed that. I did that.” That is carrying people to work. It’s carrying somebody to the doctor’s appointment. Students are trying to go to school. Everybody has to be somewhere on time. If that bus breaks down, that’s not good.

If this is what you want to do, don’t give up. I used to be a truck driver. I’ve been in a lot of male-dominated fields. You need to believe in yourself. Believe in your dreams. If it was man-made, a woman can fix it.

Grace Aiken

b. 1972, Takoradi, Ghana. Sculpture apprentice, china restoration department, Replacements Ltd., Greensboro.

I was hired to become a polisher. One day, the supervisor came to me and handed me a spoon to polish. But I looked at this spoon, it was all bent up. I took it to the sanding wheel. I was hired just three months [earlier]. I’m thinking he is trying to test me to see that I know what I’m doing. So I took the sanding wheel and I shaved the spoon and made it like a different spoon. I handed it to him, and he said, “Who did this?” I said, “I think you gave it to me, right?” They were trying to look for someone to bring into the repair department. They were testing people to see their ability. I didn’t even know there was a restoration department! I had no idea. I just did the work. The manager called me into his office and said, “You’re going to restoration.” I asked, “What is that?”

In Ghana, I was a beautician. I was a hairstylist. I started that when I was in Liberia. In 1998, there was a tribal war, and we were sent back to Ghana. I worked at a shop in Accra until I was maybe twenty-four. To be a hairstylist, you have to have the eye. If you don’t have the eye, you won’t be able to do the work.

I don’t think I like to be told to do stuff, I will go ahead and do it before you can come and tell me what I need to do. I will show them what I got if you put me in a different department. I take pleasure out of trying to see if something can be done. I want to learn one more thing, one more thing.

Horace McKee

b. 1944, Canton, North Carolina. Ceramic restoration, Replacements Ltd., Greensboro.

‘

]\I took a drawing class my senior year at UNC–Chapel Hill and I knew I had skill with my hands. This was in 1965, in the middle of the Vietnam War. I was avidly opposed to participating in the war. I had not been an ardent enough student to go to graduate school, but I still had a college deferment, so I decided to go to school to study art. I thought, “Well, if I go to school to study art, my parents are gonna kill me. And if I go to Vietnam, I’m gonna get killed.” So I decided I would take a chance on my parents.

If you’re carving wood—which is what I was doing before in art school—and you’re coming to a smooth surface, you always have to come down below that lowest point and blend everything in. It was really from carving wood that I understood how to take a chip out of a piece of china.

People don’t work with their hands anymore. And people don’t want to work with their hands anymore. We have not added a long-term person to the repair department in twenty years. If you have a good set of hands—and not everyone does—use them. It can be very satisfying.

Working with your hands opens your mind. There’s a strong connection between your hands and your mind. It is not something that is demeaning. It is not something that’s beneath you. And it can be rewarding in a multitude of ways. It can expand your understanding.

Stephen Cash

b. 1961, North Carolina. Owner, Man Mur Shoe Store and Repair Shop, Raleigh.

When I was a child, my daddy took me to work on Saturdays. We would write dates on the bottom of shoe soles, under the heel, and I have one here that says 1971. I was ten years old. I’ve been doing this all my life.

I love what I do. I love working with my hands and helping people. And I make a living at it. I’m always finding a way to do the job, regardless. If I had to spend $100 to get something that I make $10 on, I will. It don’t make any sense, but that’s just how I am. My daddy worked six days a week for a long time. Unfortunately, I’m working seven days a week. There’s just nobody to fill the void. You can’t find anybody who wants to do this. Everybody wants to make more than the president.

Shoes are being made cheaper and a lot more synthetic. When I started, most shoes that you repaired were all leather. Now you’ve got all kinds of synthetics, urethane, plastics—it’s a different process of repairing them. Back then you put a leather sole on a leather shoe. Now we have glues for attaching different plastics.

I’ve put thousands of ladies’ heels on, over and over and over and over again. I just took in a pair of boots today, she loved them. She wanted to get them fixed. It was going to be $80, but she could have probably bought a pair for $100. I think they all need a psychiatrist, in my opinion. When you get people breathing down your neck for a pair of shoes when they can buy a new pair, it’s ridiculous. But they want their shoes. Once you get through with it, it’s like instant gratification.

Toby O’Neal

b. 1943, Harkers Island, North Carolina. Owner, O’Neals Body Shop, Beaufort.

I just started painting for my friends. The oil company that I worked for had a fleet of trucks. I used to take an oil truck home on Friday night. And oil trucks are big. I would sand one of them and paint it and two-tone it and drive back to work Monday morning. Just doing a little work on the side. I would paint boats. I’d paint theater screens. On Harkers Island they had a theater with a canvas screen.

There’s been a whole lot of changes, but I say the biggest change is electronics and aluminum panels. Can’t do a thing with them. The insurance company, with anything aluminum, they just replace it. A lot of stuff can’t be repaired. Bumpers are plastic, and we have plastic weld, we can restore and weld them together, but that’s not price feasible. Probably 95 percent of my work is insurance work.

I bought this little house down here for $6,000 and built a little shop next to it. That’s how I got started, and it kept growing and growing. We’ve been fortunate. I try to treat you like I want to be treated. I’m very hands on. I don’t care who does the work. I will put my hand on the car before it leaves. It has to satisfy me, because I got to satisfy the customer.

People say, “You’re a kind person.” I say, “I ain’t got a whole lot of money. I got a whole lot of friends.” When you go, you will take nothing with you. Is there a safe deposit box in the casket? No. That’s the way you got to look at it.

Damon Walker

b. 1973, Brooklyn, New York. Luthier, Dr. Bass String Instrument Repair, Rental & Sales, Durham.

In this industry, I’ve run into a lot of bias, I think for two different kinds of reasons. Part of it is there are no Black luthiers. I’ve never read [about] one, saw one, heard of one. I’ve gone to some conferences, I belong to some of the organizations and the guilds, and I’ve not come across another young guy. Reason number two is, usually, a luthier is a really old European.

I am proud that I’ve made a space for myself, that I’ve been successful enough that I can do this alone.

I am proud that I’ve made a space for myself, that I’ve been successful enough that I can do this alone. Part of that I feel proud about, but there’s a bigger part of me that’s despairing that there’s no one to mentor me, now that I’ve left my apprenticeships behind. It’s either you apprentice and you work in my shop and I teach you everything, or that’s it. I see others professionally, they can hold the shop and there is still someone else to talk to about technique and approach and so forth. I’ve just not been afforded that. Everyone seems threatened by my presence.

Gina Paschall

b. 1963, Swainsboro, Georgia. Owner, Triangle Tires Auto Service Center, Chapel Hill.

My dad’s mother’s family were Native American and their last name was Wheeler. They made wagon wheels. I really think it is in the blood. I really do. There’s something to that. I just love tires. It’s hard to explain it. Nobody else really gets it. But they get it when they see me do the tires. They’re like, “Wow.” There’s a flow, there’s a rhythm, and just handling the tires. I don’t know, it’s just my thing.

I just love tires. It’s hard to explain it. Nobody else really gets it. But they get it when they see me do the tires.

The first time I ever did tires, they had this big, huge twenty-six-foot truck. We had gone to the landfill so that the four of them could unload the truck. And I said, “I want to unload the truck.” They looked at me and they laughed like, She must be crazy! “OK, sure.” I got in the back of the truck. It had been raining, all the tires were orange from the mud. I got back there, I unloaded the whole entire truck. I came out orange from head to toe. They’re laughing. They’re just dying laughing, because I’m just one little orange person going, “I love it!”

I think it’s really important that when you find somebody you trust, [you] stick to the person that you have trust in. We can go to chains to buy things, and to get services, but they don’t care about us. It’s the small businesses that care about the people in the community. I hope that we all can be diligent enough, care enough, be patient enough, and maybe even spend an extra 50 cents to go buy the dress from the local shop. Who we support matters, it really does matter. And if we support our communities, then we have good communities. If we don’t support our communities, in the grand scheme of things, what are we building?

Jared Huffman

b. 1982, Columbia, South Carolina. Owner, Y & J Furniture Company Inc., Durham.

I’ve always enjoyed trees. I always thought it was really interesting that the wood was kind of alive all the time. Even when it’s a table, it’s always alive, it’s expanding and contracting. As you start looking at furniture, seeing the trees it’s made out of, the history of how they put it together and the joinery, it’s fascinating.

Take a chest of drawers—you’ll see it signed by all the guys who’ve worked on it over the past hundred years. And then you’re putting your name there, that you worked on it. You’re with these other guys, you see the repairs they did. You got to learn from all those guys that know this stuff, because they’re masters at what they do. And it’s overlooked. These people are artists.

There’s a lot of sentimental stuff that comes into it for the customers. I’ve always appreciated that. They’ve had the piece of furniture for sometimes hundreds of years, or they have a memory of someone who died. There was a rocking chair. The lady’s mother was blind and she would always run her finger in the same spot. She put a groove in there. We had to restore the chair, but she said, “Don’t take that out.” We’ve had clients where their kids have scarred the table, wrote something on there, and the kid passed away. Or scarring on a table where their grandmother would cut the meat.

Winfred Daniels

b. 1936, Durham, North Carolina. Furniture stripper, Y & J Furniture Company Inc., Durham.

Each piece of furniture, you know, is different and you have to treat it like that. A person built that furniture. And the material that’s in the furniture was a living thing. So I treat it like that.

There’s always somebody standing in the wings waiting to step up and move into your footsteps.

You can’t keep this to yourself or it’ll die out. We’re called dying trades. The trades are dying out because the older guys won’t teach the younger guys. And the younger guys, a lot of them don’t want to know anyway. But there’s a few around, just enough to keep things going. It’s always that way. You think everything is going to go away and die because people are not interested. There’s always somebody standing in the wings waiting to step up and move into your footsteps.

You got to have patience with all this stuff. If you try to rush it, believe it or not, you got to come right back and do it over again. Because you’re going to mess it up. So you might as well take your time. Do it right the first time. You won’t have a problem.

Each stroke I make takes off a tiny layer of paint. And while the stripper is running over it, that loosens up the next layer. And I just keep rubbing. And I think about the good old days, and before I know it the paint is gone. My mind wanders all over the place. Good things, bad things, the old days, working various jobs. I think about those people and wonder where they are, how they’re doing. You’ll catch me sometimes talking to myself. Laughing. I think about funny things when things get tough in here. I just laugh it off. I forget about all the mental pain I’m going through fooling with this stuff.

Kenneth “Kenny” Styron

b. 1952, Morehead City, North Carolina. Styron & Son Diesel Service, Davis.

I come from a fishing family. My grandfather was a fisherman. He and my father went in business, built fish houses and boats. I just fell into doing mechanic work. When people broke down, I’d go and help. I never did go to school to learn this, I learned hands-on. My father moved back to Davis and built a freezing operation, where we froze menhaden for bait. We had an operation doing that for about twenty years. We would catch them, he would freeze them, put them in fifty-pound cartons—frozen bait. Then finally, he had a stroke in 2003. A storm destroyed it and most of the stuff, nobody kept it up, so we closed that business down. I’ve been on mechanic work since then.

There’s always someone broke down. I learned hands-on. Dropping values, breaking valve springs, any major thing can break down. Three years ago, a boy called me about seventy-five miles offshore New Bedford, Massachusetts. A local boat, they were scalloping. I flew up there, had to take the engine down, to home, got the part, and flew back up and put her back together. One time there was a dredge boat in Cameron, Louisiana. We drove eighteen and a half hours to get there. Fixed it in forty-five minutes. $1.50 part. Caterpillar and company kept working on it for three days, but couldn’t find it.

James Petersen

b. 1949, Gary, Indiana. Wind instrument repair, Jim Petersen Music Instrument Services, Durham.

Taking your instrument to somebody who purports to fix these things, it’s kind of like going to see the dark arts guy, you know? The alchemist. You have to be, in terms of dealing with the customer, “Hi, how are you today?” and explain to them to the fullest extent possible what you are doing.

You never say “bend” in front of the customer. But sometimes you have to “regulate,” “adjust,” you know, that kind of thing. If you say “bend” you can charge five bucks an hour. If you say “adjust” you can charge fifteen bucks an hour. If you say “regulate” you can charge thirty bucks an hour.

When you get to a certain level of performance, your sensibilities about what you want the instrument to do are refined. That includes not only the mechanical aspects of putting this finger down or taking that finger up, or putting the slide out into seventh position—it’s knowing what you want the horn to do, the sound, before you even open the case. The pursuit then becomes having an instrument that does that for you, and sometimes the instrument is perfect. There is a visceral relationship to the instrument, a less than completely conscious awareness. The instrument is not right until it is right.

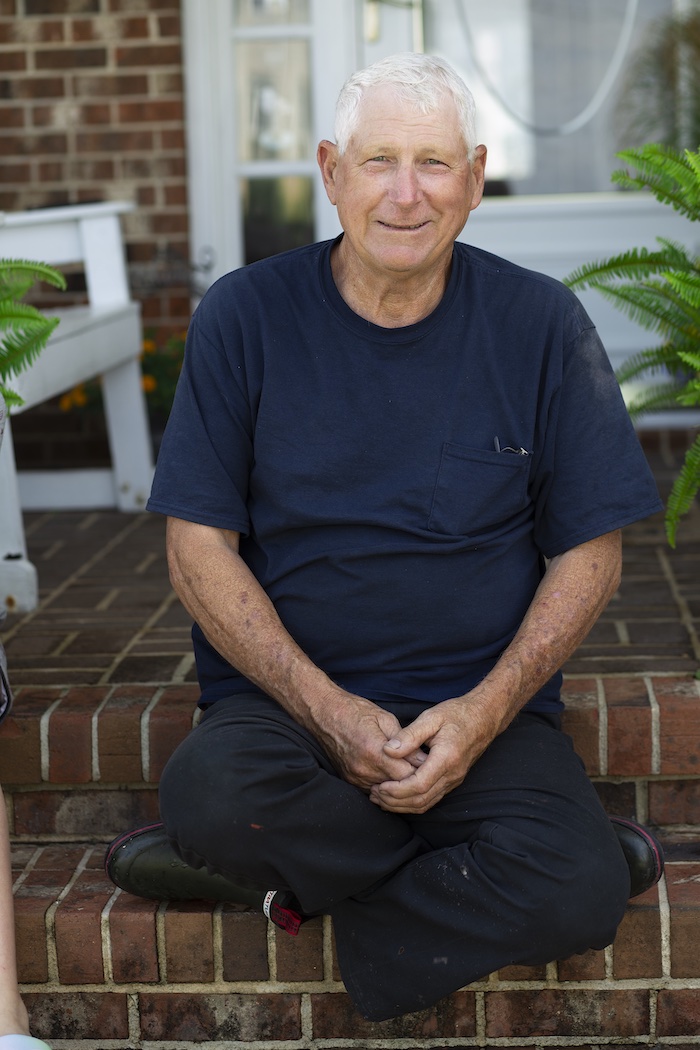

Douglas Riley

b. 1939, Hampton, Virginia. Glasses repair, Eyeglass Repairs, Durham.

I started in optics in 1976, graduated from Durham Tech in optics 1978. I had Roxboro’s only privately–owned optical shop from ’79 to ’89. In 1996, I started Eyeglass Repairs in Durham. The closest person that does what I do is two hours away.

When I started in the ’70s, opticianry was a profession. When someone couldn’t see out of a pair of glasses, it was your responsibility to deduce why they couldn’t—you had the ability, you had the equipment. Today, opticians do nothing more than type in an order.

Because there’s not a whole lot of money in it, it is an old person’s profession. I tried to give this to our daughter and grandson, and they would have none of it because there’s no corporate insurance.

I have come across frames where people have thrown away what I have repaired and it hurts. My repair should be as good as—if not better than—new. You pay me for my artisanship.

Jimmy Amspacher

b. 1944, Wilson, North Carolina. Boat building & miscellaneous repair, Marshallberg.

I don’t believe in throwing anything away. It can be fixed. If you grew up down here, you had to work. There was no such thing as laying in there pushing buttons like these kids do today. That’s all I’ve ever done is fix things. Create stuff, make it work. And make it last, you know—or try to make it last.

I don’t believe in throwing anything away. It can be fixed.

We grew up not having the ability to run down to a good hardware store. If you found a piece of metal, you could cut something out of it and use it, and that’s what you did. And if you needed a boat, you would go to the store and order the lumber, order the nails, and they’d bring it, drop it in your yard. And you went out there and built a boat like you want. And that’s how you made your living. You built your own boat. I don’t need plans. I just go build it. I got it in my head. I don’t know where it came from, but I’ve always been that way. And I built cars, I built airplanes. I’ve done everything.

I worked on a computer for thirty-one years, and I despised it every minute. Because you lose. You lose you in whatever you’re doing. I don’t text. You want to talk to me? Call me. I’d rather you come see me. I’d rather look at you and talk to you, but that’s the way it is. It’s gotten so impersonal. Everybody is destroyed with this [mimes pointing at a smartphone], getting in a car and going here to get that, dialing up Amazon, on your doorstep the next day, instead of going out there and actually trying to do something. The world is changing so fast that they’re losing contact and continuity, what really works.

Dennis Kaye

b. 1954, New York City. Horologist and owner, Advanced Clock Repair Services, Cary.

I bought a store when I was about twenty-three years old in Bergenfield, New Jersey. It was called the Wizard Repair Shop. It fixed everything, including clocks. You name it, we fixed it. Except televisions. We used to fix the embalming machines for the local funeral homes, because who else is gonna fix that, right? When I sold the store, I continued to repair clocks—that was the high-ticket item. That is how I got started. I am self-taught.

I sold the store because I realized it was becoming more of a disposable society. Not necessarily a quality change, but a change in manufacturing—retail prices were coming down. We fixed a lot of toaster ovens, an awful lot of toasters. All that stuff became throwaway.

I like that every clock, even though it’s a clock and its function is the same—every clock is different. They come in a different case. I admire the art of it.

I have been desperately seeking somebody to teach and take over this business. I hate to just sell everything for pennies on the dollar and close the door one day. They have clock schools. But not many people are doing it anymore. No one would think this is a live business. But it’s better than it’s ever been. Someone told me at one time there were twenty-five clock repair stores in Lee County, North Carolina. Now there’s zero.

You can’t teach the aptitude. It’s got to be someone who can do his own brake job, his own oil change on his car. Someone has to know how to work with their hands. Someone has to have that innate aptitude, because this involves so many things. We do the cases, we do the dials, we make all kinds of parts. It’s an art in itself.

Randy Winn

b. 1962, Martinsville, Virginia. Minister and chair caner, Stokesdale. Megan Winn (pictured right).

My father-in-law, Berlin, moved to Snow Creek in Franklin County, Virginia, in 1968. There was an old country general store, Overstreet, run by Gordon Overstreet and his wife. He was a pretty talented individual. He was blind. He lost his sight when he was fairly young. He went to a training school for the blind and learned how to cane chairs, all by feel. He and his wife, not only did they run the store, but to make ends meet they caned chairs. They taught Berlin how to cane. Years later he taught me, and then, by attrition, Megan [my daughter] got taught.

In ministry, there’s a lot of stress. People have no clue as to how much. Chair caning, at that time, was an outlet. I could put my mind in neutral and not think about anything else. I don’t think people realize the time it takes to do this. It is repetitive, but you have really got to pay attention to what you’re doing. Because you’re counting constantly, regardless of the pattern. You’ve got to count, you’ve got to pay attention to what you’re doing the whole time.

Anderson (Andy) Whitted

b. 1960, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Whitted Plaster & Stucco Inc., Hillsborough.

I had a drive that I don’t see in anybody now. When my brother and I were coming up, you had to learn whatever the family trade was. My grandfather had four sons. All his sons had to learn. Now I guess we give kids options, but when I was coming up, there wasn’t no way around. Everybody here was either plastering or brick masons.

My grandfather and uncle, they used to travel. They did union work. Plaster, groups of guys. They used to go to Goldsboro, Fayetteville, built all those places, army bases, hospitals. All those guys knew each other. But their sons didn’t take it up. I’m pretty much the last generation of it. They got away from it because it was hard work.

Scratch coat is that first coat you put on. You take a scratcher and scratch lines. That’ll make the brown screed coat, the next coat, bond. Screeding is when you take a rod and you screed the wall to get the brown coat good and level. Then after that, it’s got to dry out. That’s when you come back with your finish coat, the smooth coat, the white coat. Back then they used mud and put horsehair in it. Because when I go in and do repairs, I would see horsehair when I’m tearing out. I stayed to the old traditional way. I had a friend that got into styrofoam. I will go help him mud sometime, but I didn’t mess with styrofoam. I stayed away from it.

Lenore Gusten

b. 1956, Buffalo, New York. Co-Owner, Gusten’s Restoration Studio, Pfafftown.

Most of our clientele is aging out. So sometimes they’re fixing things so that their heirs don’t throw it out. Because they’re really afraid that nothing will be saved, that they’ll either pitch it in the garbage or send it off to Goodwill. I enjoy that stuff is not going to the trash heap. I enjoy making people happy. Because there’s a lot of people just so happy to see something as mundane as their cookie jar that belonged to mom put back together.

This essay first appeared in the Crafted Issue (vol. 28, no. 1: Spring 2022).

Katy Clune is the Virginia state folklorist and director of the Virginia Folklife Program. Through documentary projects and thoughtful communications, she strives to help folks make cultural connections. She has lived in six countries and on both coasts, and now calls Charlottesville, Virginia, home.

Julia Gartrell is an artist and educator based in Durham, North Carolina. She received an MFA in sculpture from the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work explores southern folklore, traditional craft practices, and the art of “making do.” She recently launched the Radical Repair Workshop, a traveling public art project dedicated to the idea that repair can be used as a storytelling and art-making device.

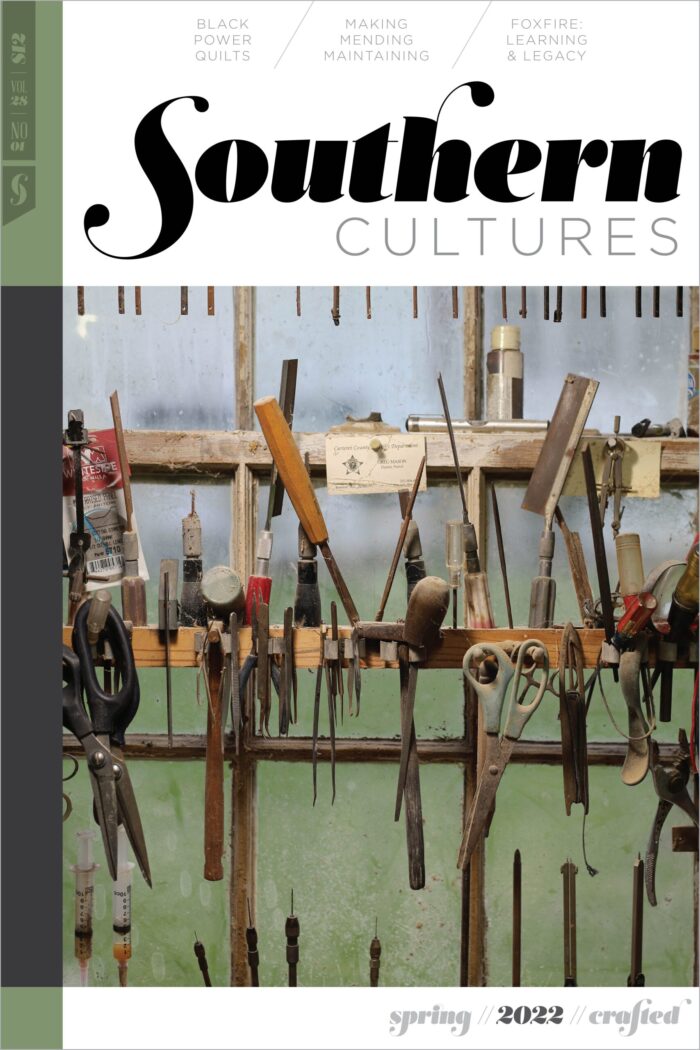

Header image: Wood cutting templates hang in the workshop of Y & J Furniture, Durham.