Saltville lies in two counties—Smyth and Washington—in southwest Virginia about thirty minutes east, then north, of Abingdon. The fossil record and artifacts found in the region, now displayed in the Museum of the Middle Appalachians, indicate that Saltville was a prehistoric salt lick attracting large mammals (like the wooly mammoth skeleton in the museum’s center) and eventually the hunters who killed them. A diorama tells the story of Civil War battles fought over control of the salt works, which were vital to provisioning Confederate troops. And black and white photographs chronicle the history of a company town that once thrived even as a steady loss of jobs and population began in the 1970s. But Saltville has continually produced salt since 1780, and the town survives.

In the gift shop, on a shelf with official histories, I once spied a large yellow book bound with plastic teeth.

In the gift shop, on a shelf with official histories, I once spied a large yellow book bound with plastic teeth. Eager and anxious, I plucked out the Saltville Centennial Cookbook, published in 1996 to celebrate “a century of good cooking.” The index of recipes includes a somewhat predictable Jam Cake and two versions of Chicken and Dumplings, but also Hungarian Goulash (Hunky Soup), Million Dollar Pickle, Dr. Finne’s Baked Doves, Brain Croquettes, Dead Man’s Soup, Paprika’s (sic) Csirke (Chicken), Bert (Big Mama’s) Cat Head Biscuits, and Little Bessie’s Tarts. Eagerly, I opened the volume at random and my eye fell on “Cora Davidson’s Rushen Tea,” a recipe that strikes me still as one part haiku and one part irritated Zen master:

1 qt. orange juice or 6 oranges

1 pt. pineapple juice

6 lemons juiced

2 cups or more sugar

Cook with several cloves and tea bags. I forget how much, be your own judge.

Serve hot.

Even more thrilling than the recipe was a photo of Cora Davidson and a brief remembrance of her written by one of her relatives. I was delighted to discover the same was true of every recipe in this book. Instead of the usual line or two headnote describing the dish, the compilers of the Saltville Centennial Cookbook asked each family to contribute a short bio, story, or memory of the specific cook. Almost all of these blurbs were accompanied by black and white snapshots of the chef.

Reading Sallie Taylor’s story, I learned not only her recipe for Chess Pie, but also that she “cooked delicious meals on her wood and coal cook stove. Yes, she also had an electric stove in her kitchen . . . ” Or that Minnie Barrett Henderson “would follow the ‘signs,’ for example, don’t cook candy or icing when the weather was rainy.” Or that CC Hatfield, MD was remembered not only for his Hunter’s Goulash recipe but also “for his sense of humor and the fact that he delivered 3,315 babies.”

I took the cookbook home with the same anticipation I would have for a new novel. And as I read more of the descriptions—“Virgie’s six boys loved her frozen cheese salad,” “Marie’s cabbage soup could feed six people or four hungry farm hands,” or “Thelma made her River Road Special Sandwiches and then sat at the kitchen counter to finish her word search puzzle”—I found myself thinking about the work of my friend, artist Amy C. Evans.

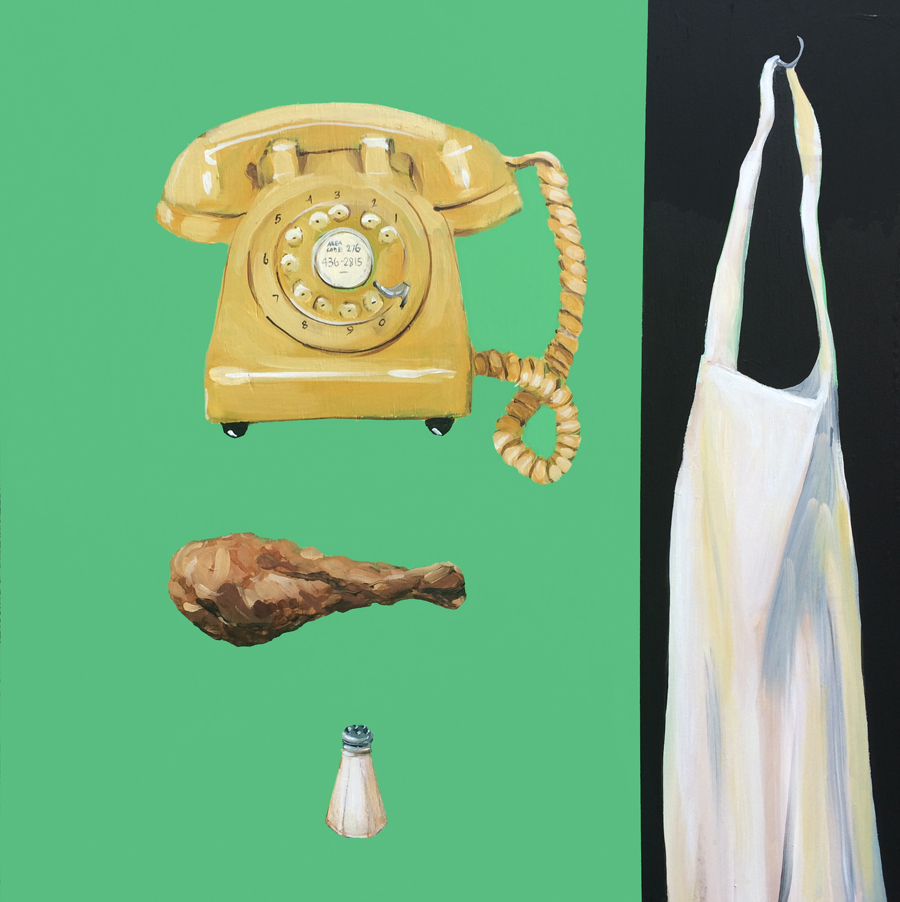

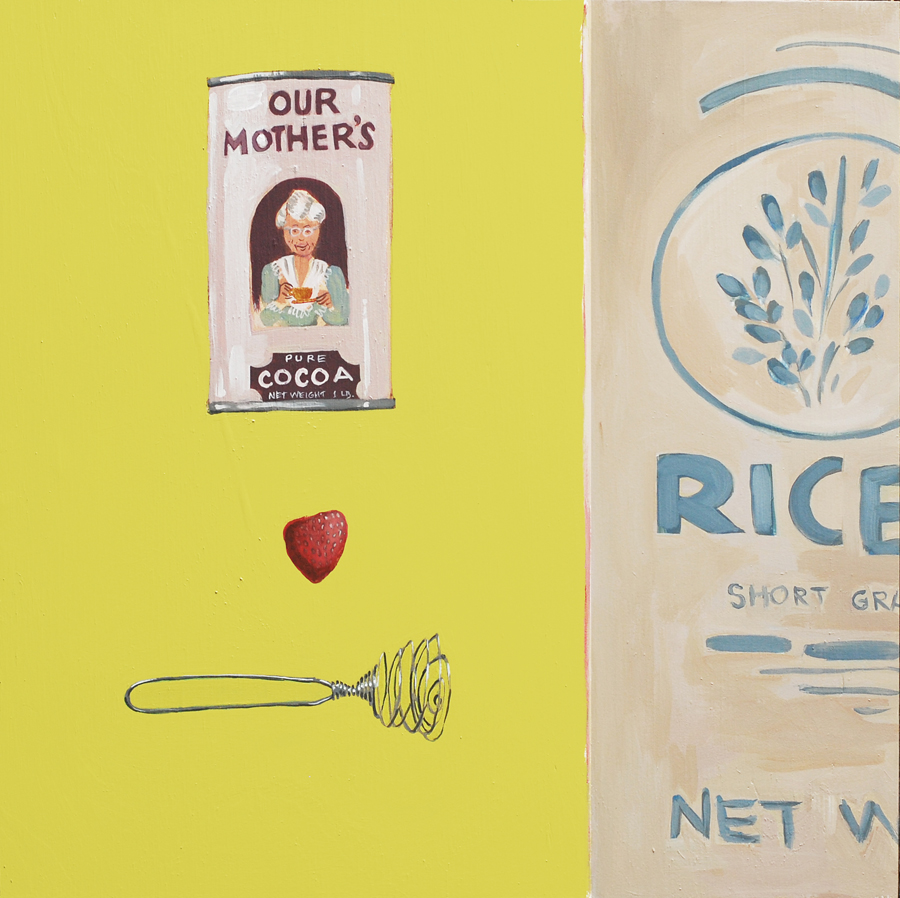

Formerly the head of the Southern Foodways Alliance’s oral history program, Amy has painted visual histories for many years now: “portraits” of imagined women consisting of three or four objects from their lives set against a solid background with a patterned border—often a tablecloth or curtain—suggesting the borders of those lives. Each painting is captioned with a phrase about the subject’s daily life.

“Agnes loved combing mayonnaise through her curls,” reads the caption of Amy’s painting of a jar of Duke’s mayonnaise encircled by a turquoise and silver squash blossom, floating above a black, plastic comb on an orange Navajo rug with rainbow border. Or there’s a tin of pimenton picante, a bobby pin, and a slice of cucumber on a field of yellow, bordered by the edge of a black lace mantilla. Titled “Dolores,” its caption reads: “Every morning, Dolores put cayenne in her water and cucumbers under her eyes.”

Every time I looked through the Saltville cookbook, a random line here or there would suddenly invoke Amy. So finally I put down the book, picked up my cell phone, called Amy and said, “Hey, can I read you something?” The results of that conversation are the following eleven women of Saltville brought to vivid life. But their creation in Amy’s studio in Houston was only the start of this artistic journey. In September of 2015, Amy packed the women in the back of her car and brought them “home” to southwest Virginia. As the artist-in-residence for that year’s Appalachian Food Summit held in Abingdon, Amy presented on the project, and the paintings were hung at Harvest Table Restaurant in Meadowview, Virginia, just a little over 12 miles from Saltville.

Ronni Lundy is the former restaurant reviewer and music critic for The Courier-Journal in Louisville, and former editor of Louisville Magazine. Her book Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes and Honest Fried Chicken was recognized by Gourmet magazine as one of six essential books on southern cooking. In 2009, Lundy received the Southern Foodways Alliance Craig Claiborne Lifetime Achievement Award. Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, with Recipes is nominated for a James Beard Award and received a 2017 IACP award for best American cookbook.

Amy C. Evans is an artist, writer, educator, and independent documentarian based in Houston, Texas. She served as the lead oral historian at the Southern Foodays Alliance for more than ten years and taught an annual documentary workshop. Amy holds a B.F.A. in Printmaking from the Maryland Institute College of Art and an M.A. in Southern Studies from the University of Mississippi. She is a teaching artist with Literacy Through Photography and has been represented by Koelsch Gallery since 1997.