On a hot Sunday in August 1990, LaToya stood inside an underground baptismal pool, surrounded on three sides by a canopy of North Carolina pine trees, the wooden-floored church building, and the community of parishioners that made up the churchgoers and leadership. At the rural church located just outside the one-stoplight town of Waco, North Carolina, her pastor recounted the story of Jesus’s baptism (Matthew 3:16–17), then dipped her into the water and spoke a common refrain in Black Baptist churches: I baptize you, my sister, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. The baptism took place after years of traveling by church van to Sunday School, taught by her aunt Shelia, an elementary school teacher who instilled in her the love of reading and learning. Sunday School lessons included reading, memorizing, and reciting lessons about love (John 3:16), strength (Philippians 4:13), and humility through the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–13).

Priscilla vividly recalls her confirmation in a Black United Methodist Church in South Carolina, by her father, the church’s pastor. She remembers kneeling at the altar and looking down at a King James Bible, while her father’s hand rested on her head as he offered a prayer. She also remembers the intense weeks of studying the Bible with her youth group, learning correct pronunciations, and making flashcards and other mnemonic devices with her mother to help her retain large swaths of scripture. She was interested in what was in the Bible, but as a child was a little more eager to show everyone in the church that she could memorize and recite more Bible verses than anyone. She was also inspired by her Sunday School teachers, who told exciting and complicated Biblical stories but made them plain and relatable. These Black women Sunday school teachers, alongside her parents, were instilling a religious and spiritual message, but they were simultaneously teaching her how to read complicated text, communicate, and write clearly.

The commonalities of our Afro-Carolina experiences include the ways we were educated through our rural religious experiences and, significantly, the role of the King James Version of the Bible (KJV) in that process. Black people’s use of the KJV is complicated, given the role of the translation in “particular forces of empire.” Less than a decade separates the 1611 publication of the KJV and the 1619 arrival of enslaved Africans to American shores, which historians Maury Jackson and Horace Crogman observe “tested not only the fortitude of a stolen people, but also the subversive power of the authorized text of Holy Scripture. For most of the Africans,” they note, “the Sacred Story initially came as an oral tradition based on and informed by the language of the King James Version.” Jackson and Crogman go on to suggest the KJV’s decisive role in the lives (and liberation) of Black people, calling for scholars to mark the four hundredth anniversaries of the arrival of the KJV and African captives “not so much for what the biblical text did to reform the church in Europe, but to commemorate its role in forming a people, who were no people.”1

Beyond its role as a sacred text, the KJV has shaped and sustained Black spatial practices in the rural South and has served as a geographic tool for Black communities. In particular, it has been used as a means of gaining literacy and, therefore, functioning to radically transform the region. We trace this transformation by culling the archives of Black women living and working in the rural South to elucidate the intersection of the KJV and southern women’s work during the twentieth century. Exploring these linkages through the lens of Katherine McKittrick’s concept of “plantation futures” allows us to narrate Black geographies not merely from the perspective of domination and dispossession but through the insurgent knowledge production of Black life—past, present, and future.2

A Partial History of the King James Version of the Bible

According to Mark A. Noll’s In the Beginning Was the Word, King James authorized the 1611 version of the Bible for three important reasons: to unify the Church of England, to show himself as a scholar and leader of the Church, and to remove portions of the previous version that “specified circumstances under which subjects could disobey their monarchs.” Noll suggests that, while the KJV is largely heralded as a beautifully written work, it also became the most used version of the Bible during the seventeenth century, in part because it was the most widely printed. In the American colonies, the KJV maintained its prominence, particularly in New England, where many of the earliest printed books were religious texts. Today, the KJV continues to be the most widely read version of the Bible.3

While the Bible has provided solace, guidance, and community for some believers, it has also been used to justify violence and oppression across the globe, including settler colonialism, the murder of Indigenous people, and slavery. South African scholar Robert Vosloo writes about the use of the Bible to justify and codify racial separation and violence during apartheid. Jakob Daniel Du Toit, an Afrikaner poet and theologian, worked to identify specific Biblical passages, particularly in Genesis and Acts, which called for separation and Black subordination. And the Bible was quoted by politicians and preachers alike to justify Jim Crow discrimination in the US South. Theologian John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, however, used the Bible to argue that slavery is inconsistent with Christianity. He preached that not only must enslavers answer before God, but those who profit from slavery and those who inherit enslaved people must answer to God. Across time and space, the Bible has been used, as intended, for varying political purposes.4

Rural Black Geographies and the KJV

Rural geography entails scholarly inquiry into sites, landscapes, and people in rural places, including the social, economic, and political processes that shape these areas. Rurality has mostly been racialized as white space, a process traced to “the idea of terra nullius—the notion of ‘empty’ lands [which] was essential to supporting white settler colonial projects in the United States and in Australia.” This process naturalized whiteness “in place” in the early formations of what we now call the United States, even with the prior occupation of rural land by Indigenous people or by significantly higher numbers of enslaved Black people in a locality than white people. Following post-emancipation Black migration out of the South, and with increased emphasis on urban issues in the press and in scholarship, the naturalized whiteness of rural areas became more pronounced.5

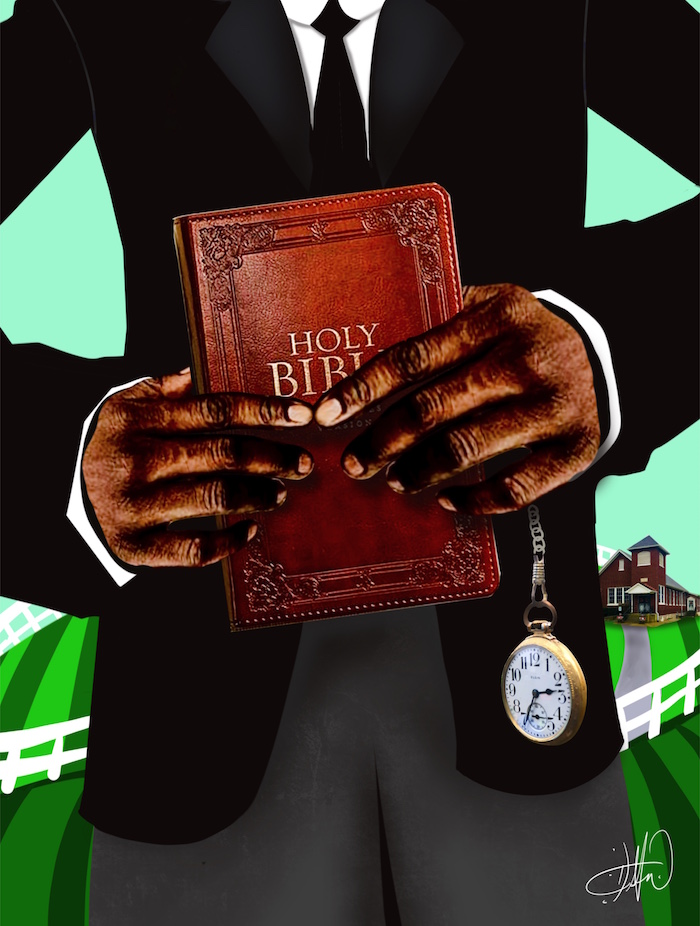

The South’s rural geographies, however, are Black geographies, the legacies of which guide scholars to and through Black locations, scales, placemaking, and knowledge production that exist alongside the histories of racial capitalism, chattel slavery, dispossession, and interlocking systems of oppression. Drawing on geographer and Black studies scholar Clyde Woods’s “blues epistemology,” a term he uses to describe the system of knowledge production and “tradition of explanation” for rural Black folk in the Mississippi Delta, we see how rural Black southerners created a “tradition of explanation” through the Black Church, using the space to explain and organize in the face of, and in resistance to, racial capitalism, white supremacy, and anti-Blackness. The KJV served as a geographic tool in that tradition of explanation for rural Black southerners. Black people, both enslaved and free, transformed the KJV into a placemaking apparatus, one in which Black southerners collaborated to develop a common social, economic, and political vision, building institutions (the Black Church) and developing socio-spatial platforms to transform the rural South into a site of belonging and transformation. Consequently, the Black Church has served as a site of Black integrity, community, support, and education.6

Black Geographies and Religion in the US South

Religious studies scholars C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya define the “black sacred cosmos” as “the religious worldview of African Americans,” “related both to their African heritage, which envisaged the whole universe as sacred, and to their conversion to Christianity during slavery and its aftermath.” Even after these often-forced conversions, these spiritual practices stayed with enslaved Africans, many of whom were Muslim. This violently imposed version of Christianity was not one of liberation and freedom but based on select Bible passages used to justify slavery and convince the enslaved that their freedom would be found in the afterlife. In the US South, particularly on the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina, the enslaved worshipped separately from their enslavers, using the cover of nature. Bush harbor services, held under the cover of trees and away from enslavers, granted the enslaved the freedom to express themselves spiritually, but also provided cover to plan escapes, revolts, and rebellions. Negro spirituals, sung in fields and during bush harbor services, contained coded messages for escape to freedom. These messages were distinct from the handpicked Biblical messages of oppression that white slaveowners told to enslaved Black people, who were forbidden to read under slave codes. Those who could read taught others in secret—and from this knowledge came a discovery that the Biblical texts being taught to them left out passages of liberation and freedom.7

The Black Church is an institution that reflects enslaved peoples’ active resistance to brutal oppression on slave plantations. Enslaved people were never passive recipients of a Christianity that taught them to accept the bondage of slavery, and Black institutions built during slavery and Reconstruction reflect this ongoing belief in freedom, liberation, and institution building. As historian and Africana Studies professor Barbara D. Savage notes, “One of the first things that free Black people do . . . in addition to being able to marry and to go in search of relatives, is that they want to build—and they do build—their own churches. I was raised in one of those churches, and these are family-run churches, and they’re formed with great pride, with the kind of religious independence and power that comes from having our own church.”8

Building churches brought economic power and social independence to newly freed slaves. In rural areas, Black people pooled their limited resources to build these institutions, which operated as meeting places for religious and secular activities. In urban areas, Black churches were built in racially segregated neighborhoods. While neighborhoods have changed due to gentrification, which contributed to declining church memberships, Black churches are often the only Black institutions that remain. Such creative pooling of resources is a result of visionary leadership. For example, Wheat Street Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, occupies almost a block of real estate on Auburn Avenue, a historically Black neighborhood with a dwindling Black population. In the early 1900s, the church owned farmland in rural Georgia that was burned down by neighboring white people. A church member, however, had the foresight to take out an insurance policy on the farmland. The funds were then used to pay off the church and provide seed money for Wheat Street’s other community programs. Though urban, Wheat Street’s story is not uncommon for Black churches in the South that face the same racist brutality and systemic discrimination that other Black institutions face. However, through ingenuity, resilience, and resource-sharing, Black churchgoers were able to build their own institutions and provide seed money and support for other institutions like farms, community centers, banks, and housing. These institutions continue to thrive today.9

Adoption of the KJV was central to the making of southern Black churches. First, as Alice Ogden Bellis, a scholar of Old Testament and Language Literature, writes, Black Christians “revere the KJV for the same reason many Roman Catholics still are fond of the Latin/Vulgate Bible: the poetry and antiquitous tone associated with a spirituality of earlier times, even another world. That some of the text is ‘mysterious,’ that is, not fully understood, is what makes it special, instantly beckoning one to prayer and active dialogue with God.” Second, Black Christians have always recognized the Bible’s liberatory potential. While the text was historically used to justify slavery and convert enslaved people to Christianity, it was also used by abolitionists in their campaigns against the oppressive institution. Just as enslavers did not abide by, practice, or preach the liberatory portions of the Bible, neither did the enslaved abide by those portions of the Bible that contained oppression. As James Cone, one of the founders of Black Liberation Theology writes, the oppressed believed that God meant for them to be free, and that the Bible mandated this.10

In our birthplaces, the KJV reigns as the utmost authority in walking with God and within interpersonal conversations away from church buildings. The isolation of rurality has led to the growth and sustainment of Black community, culture, and life since the abolition of slavery, including the practices and power of the Black Church, even in the more globalized, interconnected South of today. Inside and outside of Black Churches in the rural South, the KJV functioned as a geographic tool in two ways: through its use in literacy and knowledge production for rural Black southerners and through the labor of rural Black women.

Literacy and Black Placemaking in the Rural South

Black church histories and legacies aid in our collective understanding of the depth of oppression, violence, dispossession, and displacement experienced by our Black ancestors. Black church stories also reimagine the epistemological and ontological methods that shaped churchgoers’ everyday lives in ways that demonstrated meaning, purpose, and creation—Black placemaking. These placemaking practices were not limited to church sites. Rather, in the same way that Black church parishioners have and continue to invoke the Great Commission—“Go ye therefore, and teach all nations” (Matthew 28:19)—rural Black southerners continued meaning-making in community by disseminating the KJV in everyday life, at work, at home, and in social settings. After emancipation, the KJV scaffolded Black placemaking in the rural South through its use in literacy efforts in Black communities.

Citizenship Schools, which emerged across the South in the mid-twentieth century, used politics and economics to increase Black literacy, “aiding in the struggle to gain first class citizenship.” These schools were primarily focused on widespread voter disenfranchisement via literacy tests in the South. Birthed at the Highlander Folk School in New Market, Tennessee, Citizenship Schools were orchestrated by Black southern freedom leader Septima Clark, who was “animated by strong drives for both self-improvement and Christian service.” Citizenship School leaders used direct grassroots action and collective empowerment to recruit Black teachers and leaders into the program, training “local housewives, ministers, retired teachers, beauticians, tradesmen, seamstresses” and others to teach other Black people literacy. The program used the US Constitution and other federal government documents as educational tools, not only to teach reading and writing but also to teach principles of democracy and finances. The KJV appears in an excerpt from a Citizenship Workbook in a lesson titled “The Bible and the Ballot,” which makes use of religious text as a literacy tool, specifically the Lord’s Prayer.11

The use of the KJV in Citizenship Workbooks was intentional. By the mid-twentieth century, when Citizenship Schools were launched, rural Black southerners would have been accustomed to the sound of the Lord’s Prayer for a century or more. Many would likely have memorized the passage from a young age, in the passing down of knowledge through generations and the Black Church. The inclusion of familiar words and sounds both affirmed the humanity of rural Black southerners through empowerment and emphasized the liberatory project of the Citizenship Schools Program.

Women’s Work

What we learned about Christianity and the Bible extended beyond the one- or two-hour church services that took place each week in North and South Carolina. We attended weekly Sunday school, and Vacation Bible School was a community event in our rural towns. We learned about the Bible and remember both the lessons and the people who taught them. Our pastors were male, but those who taught us Sunday School and organized Vacation Bible School were Black women. Teaching was largely regarded as women’s work. Looking back, we realize that when women taught the Bible’s lessons, they were not only teaching us Christianity but also using the Bible to teach us language, diction, and how we should present ourselves. Whether through families, communities, or institutions, the transfer of values has always been women’s work, and sometimes this transfer of values encompassed the complex notion of “respectability politics.” According to Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, the “politics of respectability emphasized reform of individual behavior and attitudes both as a goal in itself and as a strategy for reform of the entire structural system of American race relations.”12

Central figures in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements also reflected on the importance of their Biblical teachings. Chana Kai Lee notes in her comprehensive biography of Fannie Lou Hamer, one of the most gifted orators of our time, that after leaving formal education at the age of 12, “she joined Strangers Home Baptist Church, where she continued developing her reading skills through Bible study, a road to literacy by a great many slaves and ex slaves.” Hamer’s oratory skills helped her fight tirelessly against white supremacy and poverty in rural Mississippi and ultimately across the United States. Hamer’s complex relationship with religion and the Black church meant that she often criticized Black male preachers, many of whom were middle-class, because she believed they were afraid to fight for radical change in the rural South. However, she always remained deeply religious, and her faith is evident in her speeches. In a speech given at a 1963 voting rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, Hamer says:

But open your New Testament when you get home and read from the twenty-sixth chapter of Proverbs and the twenty-seventh verse: “Who so digeth a pit shall fall down in it.” Pits have been dug for us for all ages. But they didn’t know, when they was digging pits for us, they had some pits dug for themselves. And the Bible had said, “Before one jot of my world would fail, Heaven and earth, would pass away. Be not deceived for God is not mocked. For whatsoever a man soweth, that man shall he also reap.”13

Hamer quoted Biblical verses whether she was speaking to Black rural Mississippians or to white New Englanders. The Bible is a sense of personal inspiration for Hamer, and the biblical verses she used were meant to uplift Black people to fight for liberation and freedom. Importantly, Hamer also employed biblical verses to hold white people to account for their actions. One such example is her anti-poverty message, in which she uses the Bible to remind poor whites that one such tool of white supremacy is to make them forget that they are also in the pit of poverty with Blacks. Hamer’s use of the Bible showed its liberatory capacity, but it was also a rhetorical tool she used to exhibit her oratory skills and her authority—often useful in Black religious spaces with Black male ministers. While they may have disagreed with her message or tactics—in part because she was often criticizing them for not acting swiftly and strongly enough on civil rights and social justice issues—her knowledge of the Word and command of the audience legitimized her in these spaces.

Women’s work through Biblical teachings was reflected more broadly in the passing on of values beyond religion, starting with teaching respectable values to their children. These values might include how they should speak, behave in public, dress, and even wear their hair. In Righteous Discontent, historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham discusses the roots of the politics of respectability, a response to white supremacy, patriarchy, and violence against Black women. Brittany Cooper argues that Black women historically were expected to be “race women,” who abided by the politics of respectability while still fighting for racial justice.14

Higginbotham further describes institutions that advanced “respectability” values, a prominent example being Spelman College, which “from its humble beginnings more than a century ago . . . has represented the epitome of black women’s collegiate education.” Higginbotham explores the school’s complex history, which began in the basement of Friendship Baptist Church, a Black church in Atlanta, with two white abolitionists who were also missionaries teaching newly freed Black women. Established as Spelman Seminary in 1886, the institution organized a structured schedule that revolved around biblical teachings by these white abolitionists, and other religious activities. In 1891, a separate missionary training department of seven students was founded. During the summer, missionaries in this department would travel to rural Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama to “impart to poor and uneducated blacks knowledge of the Bible, personal hygiene, temperance, family and household duties, and habits of punctuality, thrift, and hard work.” Spelman College has not been a seminary since 1926 and students no longer engage in the practice of teaching values; however, this complex association with the politics of respectability is still levied at the institution, at times taking away from the long history of student activism that continues today.15

Whether or not a school began as a seminary, many HBCUs used the Bible as a teaching tool, largely because it was readily available in homes across the South. Put simply, if most families owned Bibles, it was practical for instructors to use it to teach literacy because the lessons could then be replicated at home. However, the connection between teaching and the Bible as women’s work is important and often undervalued in a largely male-led Black church.

Based on the time frame, we can assume that Fannie Lou Hamer and the women of Spelman Seminary were being taught using the KJV. In all cases, Black women used the Bible as a literary teaching tool during periods when reading was punishable by violence or death or during times when Black people had limited access to other reading materials. Beyond its usefulness as a tool for acquiring literacy, the KJV inspired a variety of other uses. Fannie Lou Hamer recited its most complex passages but also pushed back adamantly against its patriarchal messages. And Spelman students used it as one tool to teach values to poor Black people in the rural South.

The KJV and Plantation Futures

The KJV is a liberatory text not simply because rural Black people used it. Instead, it is a discursive tool that has within it the means to oppress and to resist oppression. As Black people read and taught the KJV to themselves, they did so in its totality. Further, the liberatory practices of Black women using the KJV can be situated within what Katherine McKittrick refers to as “plantation futures,” in which she posits imagined Black geographies “as the sites through which particular forces of empire (oppression/resistance, black immortality, racial violence, urbicide) bring forth a poetics that envisions a decolonial future” working to “enable a new discursive space.” Put differently, Black geographies offers us an alternative read of place, understanding the structures of domination “in place” while also emphasizing the power and knowledge production that lies in Black lives. Here, the KJV affords us that site of knowledge production. Similarly, the use of the KJV in rural Black spaces aligns with Clyde Woods’s notion of blues epistemology, “a longstanding African American tradition of explaining reality and change. This form of explanation finds its origins in the processes of African American cultural construction within, and in resistance to, the antebellum plantation regime.”16

Black placemaking through the KJV is a form of explanation. The methods by which Black people learned and used the KJV created and sustained community, kinship, and relations to land, while also providing dignity and respect for Black people in the face of the violence and hostility of white supremacy. Black people learned this book in religious environments, at home, and in educational institutions. Teaching of the KJV was not just about proselytizing but was also about promoting literacy. Numerous other versions of the Bible followed the KJV, including the New Revised Standard Version. In 1993, noted Black theologian and rural southerner Dr. Cane Hope Felder edited the original African Heritage Study Bible to highlight the influences of people of African descent in the Old and New Testament. The version Felder used was the KJV. The KJV is a complex text yet continues to demonstrate the profound expressions of creativity and world-building in the Black US South.17

Future research will only further enliven the story of the Black US South and the use of this biblical text. Illumination can be found in our family histories, archival materials, records preserved in Black churches and community organizations, teaching materials, and literary and artistic works, as well as in ethnographic fieldwork and in conversations with Black people. This research would engage with what geographer Bobby M. Wilson urged: “We must situate race, not only in a historical context, but also in a historical-geographical context. We must expose the skeletons of places and plant the flesh of black experiences on those bones as well.18

This essay was published in the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 2: Summer 2023).

Priscilla McCutcheon was born in Denmark, South Carolina, and lived throughout the state. Much of her work has been with Black faith-based food programs and farms in the US South. McCutcheon is faculty in geography and associate director of African American and Africana Studies at University of Kentucky.

Latoya Eaves was born and raised in North Carolina’s foothills. Her research centers Black geographies and southern Black feminism. She is the Menakka and Essel Bailey ’66 Distinguished Visiting Scholar in the Wesleyan University College of the Environment and faculty in geography and sustainability at the University of Tennessee.

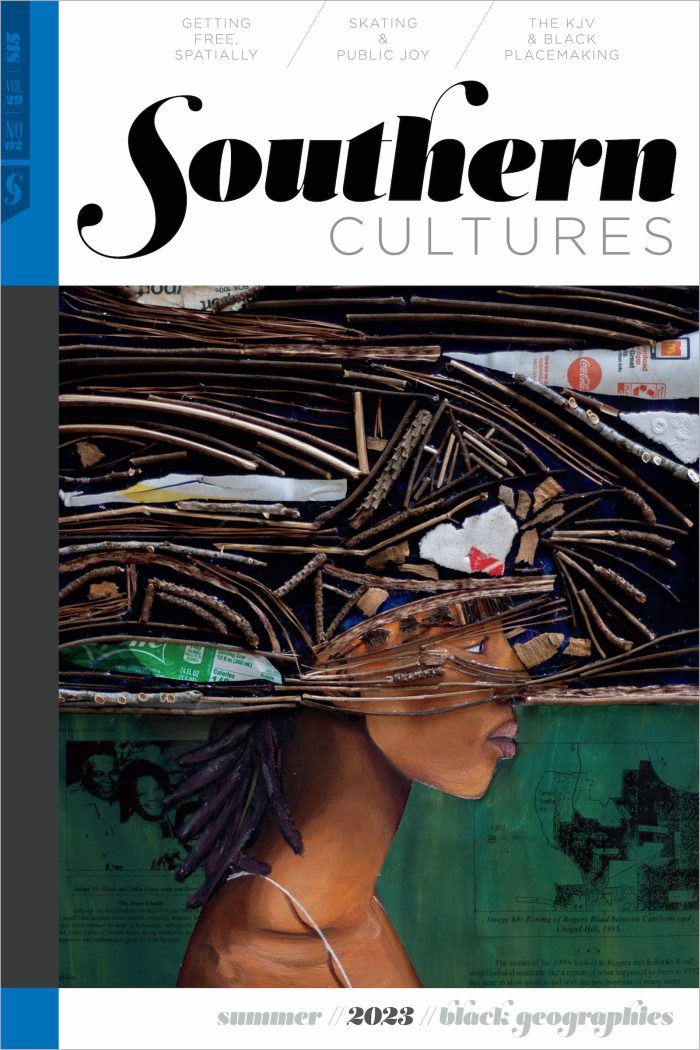

Header image: Treasured Gifts. Mixed media digital collage, by Dafri.

NOTES

- Afro-Carolina is a term coined by folklorist, educator, and geographer Michelle Lanier. See Michelle Lanier, “Rooted: Black Women, Southern Memory, and Womanist Cartographies,” Southern Cultures 26, no. 3 (Summer 2020); and “Soul Clap: Rhythm and Resilience in Afro-Carolina Landscapes,” Southern Cultures 24, no. 3 (Fall 2018). Katherine McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” Small Axe 17, no. 3 (2013), 5. Maury Jackson and Horace Crogman, “The Twisted Fate of the King James Version and the Black Religious Experience in America,” Cultural and Religious Studies 7, no. 9 (September 2019): 490–497.

- McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” 1–15.

- Mark A. Noll, In the Beginning Was the Word (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 65, 70–97; Sarah Pruitt, “Why the King James Bible of 1611 Remains the Most Popular Translation in History,” History, updated April 16, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/king-james-bible-most-popular.

- Robert R. Vosloo, “The Bible and the justification of apartheid in Reformed circles in the 1940s in South Africa: Some historical, hermeneutical and theological remarks,” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1, no. 2 (2015): 195–215; John Wesley, “Thoughts Upon Slavery,” 1773, Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/wesley/wesley.html.

- Anne Bonds and Joshua Inwood, “Beyond White Privilege: Geographies of White Supremacy and Settler Colonialism,” Progress in Human Geography 40, no. 6 (2016): 723.

- Clyde Adrian Woods, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, 2nd ed. (London: Verso Books, 2017), 25.

- C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, The Black Church in the African American Experience (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990). Rev. Angela Ford Nelson, “The Message of the Hush Harbor: History and Theology of African Descent Traditions, South Carolina United Methodist Advocate, March 1, 2019, https://advocatesc.org/articles/the-message-of-the-hush-harbor-history-and-theology-of-african-descent-traditions. “Wade in the Water” is one example of a Negro spiritual with coded messaging. The chorus, “wade in the water, wade in the water, wade in the water, God’s gonna trouble the water,” is a reference to the enslaved escaping via waterways so that their footsteps could not be traced.

- Barbara D. Savage, as quoted in Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (New York: Penguin Press, 2021), 74.

- Priscilla McCutcheon, “Food, Faith, and the Everyday Struggle for Black Urban Community,” Social and Cultural Geography 16, no. 4 (May 19, 2015): 385–406, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.991749.

- A. O. Bellis, “The Bible in African American Perspectives,” Teaching Theology and Religion 1, no. 3 (1998): 162; James H. Cone, God of the Oppressed (Ossining, NY: Orbis, 1997).

- Annell Ponder, “SCLC Citizenship Education Program” (Civil Rights Movement Documents and Materials Citizenship Education Program [Citizenship Schools] 1954–1966, n.d.), https://www.crmvet.org/docs/sclc_cep_ms.pdf; David P. Levine, “The Birth of the Citizenship Schools: Entwining the Struggles for Literacy and Freedom,” History of Education Quarterly 44, no. 3 (2004): 388–414, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3218028.

- Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 218.

- Fannie Lou Hamer, Maegan Parker Brooks, and Davis W. Houck, The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It like It Is (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011); Chana Kai Lee, For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (Champagne: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 7; Hamer, Brooks, and Houck, The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer, 5–6.

- See Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent, and Brittany Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (Champagne: University of Illinois Press, 2017). The politics of respectability, which applies to both Black women and men, is a conscious or unconscious act that might include how Black people speak, dress, wear their hair, and even where and how they are educated. The politics of respectability should not be boiled down to a “desire to be white” but, rather, understood as a past and present response to living within a system of white supremacy, where one might employ these tactics to keep safe from police violence, gain access to educational institutions and employment, or seek security and advancement.

- Higginbotham, 45, 49; Lawrence Otis Graham, Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class (New York: Harper Collins, 1999).

- McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” 5; Clyde Adrian Woods, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, 2nd ed. (London: Verso Books, 2017), 25.

- Daniel Silliman, “Died: Cain Hope Felder, Scholar Who Lifted Up the Black People in the Bible,” Christianity Today, October 2, 2019, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2019/october/died-cain-hope-felder-bible-scholar-african-american.html.

- Bobby M. Wilson, “Critically Understanding Race-Connected Practices: A Reading of W. E. B. Du Bois and Richard Wright,” The Professional Geographer 54, no. 1 (February 1, 2002): 31–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00312, 37.