“‘Blocks for Freedom’ helped dozens of poor Black Mississippi women fight for the right to vote—not with marches and sit-ins but through making clothes, selling lunches, and hosting concerts.”

In 1966, two women from drastically different backgrounds launched an innovative campaign to protect African American women’s voting rights in Mississippi. Oberia Holliday was a thirty-four-year-old Black Mississippian born to a family of poor farm laborers during the Great Depression. Jacqueline De Sieyes Bernard, a forty-five-year-old French native living in Manhattan’s Upper Westside, was the daughter of a wealthy entrepreneur and diplomat and an alumna of Vassar College and the University of Chicago.

Throughout that spring and summer, this unlikely pair led a drive called “Blocks for Freedom” to build a fireproof factory in Clay County, Mississippi, where a group of working-class Black women needed protection from the local Ku Klux Klan. These women were members of a coop that produced small sewn goods such as children’s dresses and Christmas ornaments. The factory employed eighteen full-time workers, with dozens more who contributed sporadically. They called themselves the Una Sewing Co-operative. And they were all voters.

“Blocks for Freedom” helped dozens of poor Black Mississippi women fight for the right to vote—not with marches and sit-ins but through making clothes, selling lunches, and hosting concerts. Their methods may have been overtly domestic, but the stakes of their activism were as intense as those of any other fight in the movement, as these women stared down political violence to protect their right to vote in the months after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Oberia Holliday and Jacqueline Bernard never met, but for one summer they wrote to each other often. Holliday received Bernard’s address through her involvement with civil rights activism in her native Clay County, a place that sits in a rural, somewhat isolated region of the state, over one hundred fifty miles away from the more famous Mississippi Delta or the capital city of Jackson. Known as the Blackland Prairie, the region is hot and humid, with a long growing season ideal for cotton. Holliday was born there in 1932. Her parents, like their parents before them, were impoverished Black farmers working on rented land.1

Most Black people in Clay County were quite poor. At a time when the federal poverty rate was $3,335 for a family of four, 84 percent of Black families in Clay County earned less than $3,000 a year. The median income in the county was $1,330 for African American families and roughly $4,700 for white ones. Nearly all employed Black men and women worked in domestic service or as farm laborers.2

Civil rights came later to Clay County than other places in Mississippi. A local beachhead wasn’t established until John Buffington of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) arrived to set up an office during the famous 1964 Freedom Summer. Jacqueline Bernard’s son, Joel, was one of the hundreds of white volunteers who came to Mississippi that summer to aid the Black freedom struggle.3

Joel Bernard was an eighteen-year-old junior at Cornell University when he arrived in Clay County in 1964. Throughout that summer, Joel wrote letters to his parents describing his daily activities and the conditions facing the Black people he was trying to help. The poverty was stunning, and Joel was taken aback by “the dirt, the heat, the resignation.” The economic conditions prevented more people from joining the movement because they faced potential financial repercussions for activism. The people, Joel wrote his parents, “were afraid of losing their jobs” if they signed up for a mock voter registration drive. Joel described some encouraging examples of progress but also stressed the need for money. “I urge you all, if you can,” he penned, “to give money to SNCC.” Jacqueline Bernard sympathized with the people her son was trying to help and felt compelled to get involved.4

acqueline De Sieyes Bernard was the daughter of a French count, Jacques De Sieyes, an aviator and war hero in World War I who moved to the United States in the 1920s and operated a successful perfume business before becoming secretary of the French Embassy in Washington, DC. During World War II, De Sieyes served as a personal emissary between Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French movement, and the United States government. Jacqueline grew up wealthy in Washington, DC, and graduated from the prestigious Madeira School in Northern Virginia before moving on to matriculate at Vassar and the University of Chicago. After finishing college, she moved to Mexico to work for a news magazine. While there, she met and married Joel’s father, Allen Bernard, whom she divorced in the early 1950s.5

During Freedom Summer, acqueline joined the group Mississippi Project Parents. As chair of the organization’s publications committee, she helped collect letters from other Freedom Summer volunteers that were reprinted in local newspapers and later published in the collection Letters from Mississippi. Her greatest contribution was raising money for office supplies and other materials needed by civil rights organizers. As her son emphasized, “the eventual success of the project in West Point will depend upon the support we get from the North.”6

Jacqueline Bernard continued supporting the local movement when Joel decided to remain in Mississippi after the end of the summer. That November, she helped organize a bail fund for local Black activists who might not have the resources to secure release from jail. “Most white volunteers,” she wrote to a potential supporter, “have relatives or acquaintances who can get them out of jail in a pinch … [but] many young Negroes who are giving their energy to the struggle have no bail money.”7

Bernard’s concern for local people soon extended into the realm of subsistence. The letters she received from her son revealed that local African Americans desperately needed basic necessities, such as food, clothing, and shelter. Bernard turned to some of her allies in the Riverside Democrats, a progressive organization based in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. This group had been supporting civil rights in Mississippi for several years, most notably in 1963 when they helped send a shipment of food to African Americans in the Delta who had been removed from welfare rolls in retribution for civil rights activities.8

In December of 1964, the Riverside Democrats launched a Christmas clothing drive for needy Black families in Clay County. Soon thereafter, individual women from Clay County began writing Bernard with specific requests for clothing. Bernard had trouble keeping up with demand, especially as it became increasingly clear that some of the packages were not reaching their intended recipients because of racist postal workers and law enforcement officials who were suspected of discarding packages on the side of the road. Bernard was so inundated with requests for clothing that she had to beg local leaders, “please, again, —no more names for a while!”9

While the clothing shipments were helpful, a lack of apparel was only one issue facing the poor Black people of Clay County. The realities of physical violence were much more frightening. That autumn, some unknown group burned a Black church in rural Clay County. A few days later, Klansmen burned six crosses in Black neighborhoods, causing several churches to begin turning away civil rights organizers for fear of further attacks. “It’s pretty scary working the rural [areas],” reported Joel.10

Violence and harassment escalated into 1965. That summer, vigilantes fired more than five dozen rifle and shotgun blasts into a local civil rights office. A week later, a white man entered the same building and held a pistol to the neck of a local Black youth activist. Soon thereafter, another car of local white people fired shots into movement headquarters. This time, a handful of local Black people shot back. Some of the local people knew at least some of the assailants, but calls to the fbi generated no real investigation or arrests. In fact, when agents came to investigate, the civil rights activists felt as if they were the ones being interrogated. “We have clear knowledge—as does the FBI,” concluded one civil rights worker in August 1965, “that neither local law enforcement officials nor justice department agents are going to investigate crimes perpetuated against us.” Another report on violence concluded, “People will be hurt or killed if the Sheriff and FBI remain as irresponsible as they have been so far.”11

Local white supremacists also used economic retribution to prevent movement activities. People were evicted from their homes or fired by their employers for attending civil rights meetings or transporting activists. Members of SNCC were blacklisted from renting property from local white landlords. Even Black property owners were hesitant, afraid as they were of a “bomb or bullet,” wrote Joel. “Negroes who speak out can’t get loans or credit or supplies.” Local Black residents were also having a difficult time with a corrupt welfare agent who forced people and their children to perform labor on her parents’ farm, threatening to cut them off welfare if they didn’t complete the work.12

By the summer of 1965, Jacqueline Bernard was corresponding directly with movement leaders and local residents in Clay County, continuing her participation even after Joel left Mississippi to return to college in the fall of 1965. This involvement placed her in contact with John Buffington, SNCC‘s project director in Clay County. The pair exchanged several rounds of correspondence related to clothing donations before Buffington suggested that Jacqueline focus on a project he was “most concerned about.” Eighteen women had started a sewing co-op that would allow them the financial independence to vote. Buffington suggested that Bernard focus her attention on helping this organization, known as the Una Sewing Co-op.13

The Una Sewing Co-op was created by a group of working-class Black women in Clay County in the summer of 1965. Led by president Oberia Holliday, this collective kickstarted their company by selling tickets to a gospel concert and peddling box suppers to pay for the rewiring, painting, and weatherproofing of their small wooden factory. They also secured six donated sewing machines, although two of those needed repairs.14

The Una Sewing Co-op was part of a larger organization named the Poor People’s Corporation (PPC), an offshoot of SNCC that collected and distributed merchandise from other cooperatives across the state. The PPC was intended to help protect the political autonomy of working-class African Americans by providing jobs that would free its workers to participate in politics. Voting was central to this marriage of labor and political freedom. In fact, everyone affiliated with the PPC was required to register to vote.15

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, passed just weeks before the formation of the Una Sewing Co-op, effectively guaranteed all Black Mississippians the right to vote for the first time in state history. African American men had first won that right in 1870 with the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, but the franchise was taken away from Black citizens through the nefarious voter suppression techniques crafted as part of Jim Crow. Literacy tests, written into the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, required individuals to pass exams given by a white registrar. The answers to these questions didn’t effectively matter because the literacy tests gave the registrar sole discretion over the evaluation of an applicant. Most registrars simply passed or failed applicants based on their perceived race. Because of these techniques, only 6.7[End Page 34] percent of age-eligible Black Mississippians were registered to vote as late as 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended that practice by sending in federal registrars to directly register Black voters in Mississippi and other places across the South where they had been systematically denied the right to vote.16

Clay County received three registrars in October of 1965. Local movement leaders were energized and thrilled. “Clay County now has its own Federal Registrar and we hope he will give a boost to our own voter registration drive,” Buffington wrote. Within weeks, the number of registered Black voters in the county increased from nine to over five hundred. Local leaders planned political education classes to instruct the new voters on the functions of local government. “If we can register a few thousand Negroes,” SNCC hoped, “we might make a good show with our own candidates in the coming 66 elections.” By the following January, roughly eighteen hundred African Americans had registered to vote in the county.17

But they were not yet completely free. Although local white supremacists could no longer control voter registration, they continued to use physical and economic intimidation to prevent African Americans from trying to vote. The local Klan relentlessly menaced Black activists, and white officials maintained control over access to jobs and welfare. To be truly politically independent, Black people needed to secure some modicum of economic power. “Our preoccupation with economics is behind everything we do,” concluded one report from that fall.18

In November of 1965, the Una Sewing Co-op secured a five-hundred-dollar grant from the PPC. This helped them get started, but the co-op still had five primary needs: sewing machines, scissors, fabric, thread, and a new building. “The present building of the sewing co-op is build [sic] of wood and very old,” Buffington reported. He also said that the old building was a potential target for attacks. “The white community strongly oppose the Una Sewing Co-op. There was already [been] talk of burning the old building.” What the Una Sewing Co-op needed was protection. Buffington suggested that they could be safer in a fireproof building and proposed a fundraising campaign called “Blocks for Freedom” to raise the money to pay for the structure.19

To build their new factory, the women of the Una Sewing Co-op estimated they would need thirteen thousand blocks. At twenty-five cents per block, it would cost $3,250 to secure the building materials needed for their fireproof factory. Oberia Holliday was going to donate land for the site, and a group of skilled Black construction workers volunteered their labor to erect the building.20

In February, Bernard’s New York City group leaped into action. The Riverside Democrats, who by then were veteran political organizers with experience fundraising for civil rights, employed tactics that had worked in the past—canvassing, sign posting, and sidewalk tables. This campaign was fairly easy to formulate because it had a single, obtainable goal and a set cost. Anyone with spare change could make an individual donation.21

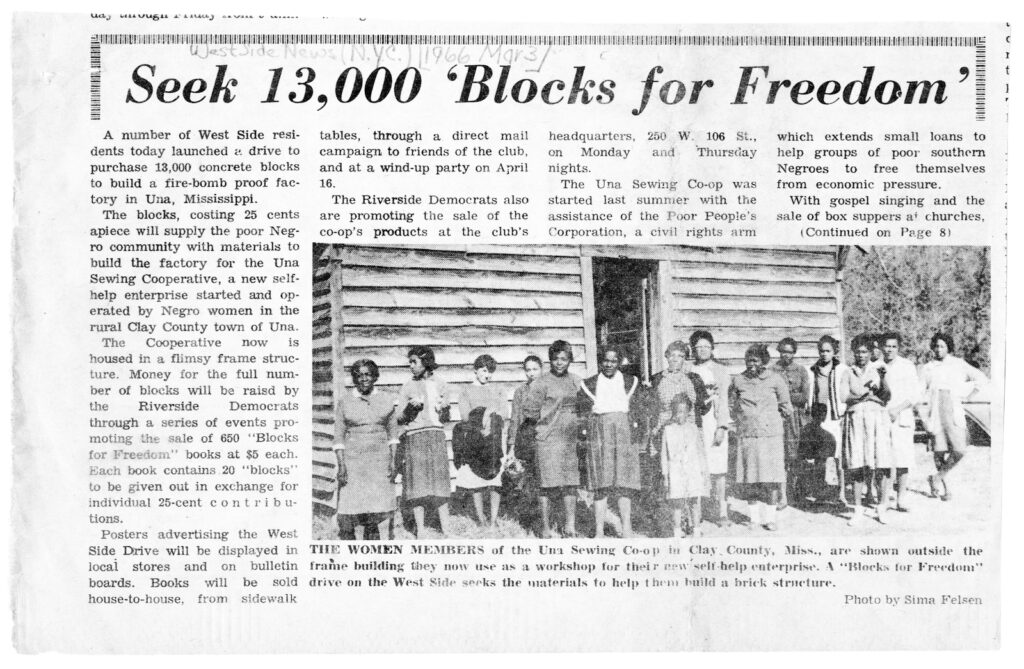

On March 3, 1966, the Riverside Democrats issued a press release outlining their “Blocks for Freedom” campaign, which was scheduled to run for six weeks between March 3 and April 14. A newsletter to “friends” was mailed concurrently with the announcement. There was an urgency to the letter, rooted in the threat of violence that could cripple the co-op at any moment. “A single small fire-bomb hurled at the frail Una ‘factory’ would be enough to wipe out in 30 minutes an entire community’s investment of time, work, money—and hope,” the authors emphasized. “WILL YOU HELP?” the press release asked in capital letters printed under an image of the co-op workers in front of their current wooden factory. Each mailer included a small tearaway sheet that donors could return with a check to the “Blocks for Freedom” treasury.21

On March 3, 1966, the Riverside Democrats issued a press release outlining their “Blocks for Freedom” campaign, which was scheduled to run for six weeks between March 3 and April 14. A newsletter to “friends” was mailed concurrently with the announcement. There was an urgency to the letter, rooted in the threat of violence that could cripple the co-op at any moment. “A single small fire-bomb hurled at the frail Una ‘factory’ would be enough to wipe out in 30 minutes an entire community’s investment of time, work, money—and hope,” the authors emphasized. “WILL YOU HELP?” the press release asked in capital letters printed under an image of the co-op workers in front of their current wooden factory. Each mailer included a small tearaway sheet that donors could return with a check to the “Blocks for Freedom” treasury.22

That same morning, the local West Side News and Morningsider ran a feature about the organizing drive. It included a picture of the women in front of their existing wooden factory and provided readers with basic information about the campaign, including instructions for anyone who wanted to donate or volunteer. The news story was backed by a series of flyers posted across Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Organizers also set up tables near the entrances of neighborhood grocery stores and convinced a local bank to allow a display in one of their windows.23

The beauty of the “Blocks for Freedom” campaign was in its democratization. Everyone could participate. Rather than seeking a big check from a single wealthy donor, the Riverside Democrats scraped together small donations from many different sources. Early in the campaign, the most effective fundraiser was an eleven-year-old girl named Kim Turgeon, who raised seventy dollars by “ringing her neighbors’ doorbells” in a Manhattan apartment complex. A thirteen-year-old girl named Nancy Stuber convinced a club at her school to sell blocks door to door. The Columbia University branch of the Congress of Racial Equality sold nearly three hundred blocks by calling movement supporters and mailing flyers. Additional blocks were sold to students and faculty at Columbia University and to passersby strolling through Manhattan’s Upper West Side.24

The drive formally closed on the night of April 14, when the Riverside Democrats made their final push with a “grand finale party” they dubbed “Ballads and Belly Dancers.” The event featured the internationally known singing couple Gene and Francesca Raskin alongside folk singer Judy Markewich. A Turkish belly dancer offered a demonstration and a short lecture on Turkish culture. Organizers also raffled a graphic print donated by a local art gallery. Tickets cost $4.00 for couples and $2.50 for individuals.25

Just a week after the close of the formal campaign, another forty-five dollars arrived from an unlikely source. Nicky Lyons, a former Golden Gloves champion and the boxing coach at the Clinton Youth Center in New York City, read about the campaign in the West Side News and Morningsider and asked his teenage boys if they wanted to get involved. On April 25, his team of teenage boxers put on a special “Blocks for Freedom Boxing Show” and donated the proceeds to the campaign.26

That May, Bernard sent a check for $2,325 to the women of the Una Sewing Co-op. The “Blocks for Freedom” campaign was still roughly nine hundred dollars shy of its six-week goal, but the total raised was nevertheless a significant amount of money to support the Mississippi women. Bernard and her allies planned to raise the rest through individual contributions sold through churches and other community organizations.27

“We appreciate this so much,” Oberia Holliday responded on behalf of the Una Sewing Co-op in a letter signed by everyone in the group. The women were excited to get to work, knowing that for the first time in their lives they were going to have a chance to earn a decent living that would protect their right to vote. “I just can’t believe this is true,” Holliday stated. “We are going to begin work right away.”28

Two days later, Bernard sent off another mailing to New York City parents whose children had volunteered in the South. She got the list of parents from an old contact in SNCC and appealed to parents like herself, asking for help with “a civil rights project that only needs a little boost over the finish line.” She enclosed self-addressed envelopes and a form for parents to return along with a contribution. Another similar mailer was sent by the Riverside Democrats to local leaders.29

Meanwhile, the members of the Una Sewing Co-op continued working on their craft. Oberia was not only president and fundraiser but also the manager, and she struggled to ensure consistent craftsmanship. When some of the Co-op’s goods were returned by the PPC outlet house for poor quality, she helped members of the group establish production standards. Holliday even told PPC managers that she was “glad” for items to be sent back because “she says it’s quite difficult to get the group to see individual responsibility and pride in the items they make.” PPC officials were nevertheless encouraged by the Una group. Later that summer, one administrator called them “the most advanced of all in terms of spirit, resourcefulness.”30

In June, Bernard sent another check for $254 to the Una Sewing Co-op, funds she collected from local Jewish and Catholic congregations and the efforts of a Puerto Rican radio host. Later that summer, she sent another payment of twenty-five dollars from “long promised checks that trickled in.” By then, however, Bernard was getting concerned. She had not heard back from Holliday after the June donation, and her further efforts at fundraising were stymied by a lack of communication and general fatigue. Bernard wrote to Holliday informing her, “I cannot work anymore on this,” but “I and my friends are interested in your co-op and would like to keep in touch and know what is happening to you.”31

Oberia wrote back that August and September, reporting on some of the difficulties the coop faced in completing their building. The women had a tougher time than expected finding labor, and the PPC had promised some additional aid that had yet to arrive. The co-op was still producing their goods for sale through the PPC, but the building remained unfinished. Holliday sent some images to show Bernard their progress and promised that Bernard would “hear from us again real soon.”32

The following October, Bernard performed the most generous gesture of the entire campaign when she took out a personal loan for three hundred dollars and mailed it to the Una Sewing Co-op. Her plan was to organize another round of fundraisers in the Spring to pay herself back. “I hope the rest of the work will go well and swiftly and that the co-op building will be finished before the cold comes,” Jacqueline told Oberia.33

By then, the building was under construction. Holliday sent images of the progress along with her response to Bernard’s last donation. She noted that they had installed two gas heaters and were in the process of adding cabinets. “It is remarkable to most people to see us in such a nice place. … We really thank you and everyone for what you done for us,” Holliday shared. “It have meant the world to us.”34

Over the ensuing weeks, local activists completed work on the new Una Sewing Co-op. The women moved into their new factory and continued making their products that ensured a living wage and protected their right to vote. The correspondence between Jacqueline and Oberia ended with the closing of the “Blocks for Freedom” campaign as each woman turned her attention to other matters—Jacqueline with a bevy of other causes and Oberia with the business of running her co-op. Oberia did send another letter the following September, updating Jacqueline that the coop was “making dolls and dresses now.” She also shared the disturbing news that two local white men had recently stopped and harassed her on her way to a meeting of the local voter league. “I was really afraid,” concluded Oberia. “Hope things are fine with you, Mrs. Bernard.”35

Despite achieving their goal of a new factory, the Una Sewing Co-op met some problems in 1967. The group experienced some infighting over work habits and pricing. Oberia felt that some of the employees of the factory didn’t take the job very seriously. The work was slowed by tardiness and too much socializing on the job. Some of the workers had concerns over the wholesale prices charged by the PPC. And in May, some of the women went on strike. Holliday, discouraged by the tension, eventually left the group she helped start.36

But the company itself persevered. Despite some internal difficulties, the Una Sewing Coop lasted for several more years. Two years after Holliday left, the group was reported to be “working very smoothly” and “heavily involved in community activities.” Their main source of trouble was over communication with the PPC itself, which experienced a bevy of managerial and funding problems before closing in 1974.37

In 1969, Ebony magazine sent a reporter to visit Mississippi to measure progress in the Magnolia State since Freedom Summer. The article pointed out some disappointing continuities for Black Mississippians, especially the poverty. But there were some positive signs of change. One of the sites Ebony visited was Clay County, where the magazine’s reporters snapped photographs from inside the cinder block building occupied by the Una Sewing Co-op. The article credited the co-op with having “supplied financial aid and new skills to poor blacks.”38

The building constructed by the “Blocks for Freedom” campaign was later criticized as “badly designed” with “not enough light,” but it accomplished its initial purpose and more. For years, it provided a space where those women workers could labor in peace to protect their right to vote. As might be expected, the building became something more than just a factory. It became an essential safe space used to host a variety of community events, including political meetings and youth gatherings. One of the final reports on the co-op noted that the women were “Planning more fund raising and youth activities for the building on weekends.”39

The women of the Una Sewing Co-op were the first in their families to vote. They were also among the first generation who had to navigate the earliest voter suppression techniques used to stymie Black political power in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. Their efforts demonstrated a new political opportunity forged out of much older community organizing traditions. These Black women used the skills passed down among generations to find new allies as they continued to search for pathways to political freedom. Most important, they defied the odds to secure the vote.

William Sturkey is an associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania whose research and writing examines race in the postbellum South, the Civil Rights Movement, and African American working-class life.

Header image: Poor People’s Corporation sewing patchwork animals, Mississippi, 1970. By Doris Derby, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Doris A. Derby.

NOTES

- Holliday background crafted using US Census data from 1940 and 1950, available through Ancestry.com.

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Research, “Clay County, Mississippi,” box 2, folder 4, Poor People’s Corporation records, 1960–1967 (hereafter PPC Records), Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

- Joel Bernard to “Folks,” August 1, 1964, box 1, folder 1, Jacqueline Bernard Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

- Joel Bernard to “Folks,” August 1, 1964, box 1 folder 1, Bernard Papers.

- Linda Wolfe, Love Me to Death: A Journalist’s Memoir of the Hunt for Her Friend’s Killer (New York: Pocket Books, 1998), 7–10; “Aide in U.S. Leaves to Meet De Gaulle,” New York Times, February 20, 1941, 9.

- Joel Bernard to Parents, November 4, 1964, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; Jacqueline Bernard to Parents, New York City, 1964, Elizabeth Sutherland Martinez Papers, 1964–1966, Micro 790, Reel 1, pt. 1, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

- Jacqueline Bernard to Ruth Singer, New York City, November 11, 1964, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- “SNCC Continues Work in North, South, Aids Negro Voters, Welfare Recipients,” Barnard Bulletin, April 11, 1963, 1.

- Jacqueline Bernard to Stan Cohen, New York City, undated, 1964, box 1, folder 2; Jacqueline Bernard to Jay Lockard, November 7, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; letters found in box 1, folders 1–3, Bernard Papers.

- Joel Bernard to Parents, November 4, 1964, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers.

- Memo, Clay County, MS, August 20, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; John Hardwick to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, October 1, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers.

- Memo, Clay County, MS, August 20, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; John Hardwick to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, October 1, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; Joel Bernard to Dear Friends, November 23, 1964, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; Joel Bernard to Dear Folks, March 12, 1965, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers; John Hardwick, “Welfare Reports,” n.d., box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; and “Clay County Project Report,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- John Buffington to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, n.d., 1965, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers; John Buffington to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, October 19, 1965, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Una Co-op Bylaws, box 1, folder 8, PPC Records; Oberia Holliday to Mrs. Douglas, Prairie MS, October 7, 1965, box 1, folder 3, PPC Records; Riverside Democrats, “Blocks for Freedom Committee,” press release, March 3, 1966, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers.

- William Sturkey, “‘Crafts of Freedom’: The Poor People’s Corporation and Working-Class African American Women’s Activism for Black Power,” The Journal of Mississippi History 74, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 25–60.

- Doug McAdam, Freedom Summer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 26.

- John Buffington to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, n.d., 1965, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers; “Voter Registration,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- “Future Plans,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Clay County Project Report,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- Freedom Information Service, “Poor Peoples’ Corporation Grants Funds to Six New Self-Help Groups,” press release, December 1, 1965, box 1, folder 8, PPC Records; “Clay County Project Report,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; John Buffington to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, n.d., 1965, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Freedom Information Service, “Poor Peoples’ Corporation Grants Funds to Six New Self-Help Groups,” press release, December 1, 1965, box 1, folder 8, PPC Records; “Clay County Project Report,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; John Buffington to Jacqueline Bernard, West Point, MS, n.d., 1965, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- “Just a Reminder,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- Riverside Democrats, “Blocks for Freedom Committee,” press release, March 3, 1966, box 1, folder 1, Bernard Papers.

- “Seek 13,000 ‘Blocks for Freedom,'” West Side News and Morningsider, March 3, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “‘Ballads and Belly Dances’ To Aid Southern Negroes,” West Side News and Morningsider, April 14, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Blocks for Freedom Committee—S.O.S.,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- “Blocks for Freedom Committee—S.O.S.,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Community Spirit on the West Side,” flyer, box, 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Blocks for Freedom Drive Seeking $925 Balance,” West Side News and Morningsider, May 5, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- “‘Ballads and Belly Dances’ To Aid Southern Negroes,” West Side News and Morningsider, April 14, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Riverside Democrats,” press release, April 11, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; “Blocks for Freedom Committee—S.O.S.,” box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers; and Stuart Lavietes, “Eugene Raskin,” obituary, New York Times, June 12, 2004, C8.

- “Riverside Democrats,” press release, May 30, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- “Riverside Democrats,” press release, May 2, 1966, box 1, folder 3, Bernard Papers.

- Oberia Holliday to Jacqueline Bernard, Prairie, MS, May 12, 1966, box 1, folder 2. Bernard Papers.

- Jacqueline Bernard to Parent of a Civil Rights Worker, New York City, May 14, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers; Riverside Democrats form letter, May 14, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Prairie Notes, May 31, 1966 and July 22, 1966, box 2, folder 20, PPC Records.

- Jacqueline Bernard to Oberia Holiday, New York City, June 15, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers; Jacqueline Bernard to Oberia Holiday, New York City, August 13, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Oberia Holliday to Jacqueline Bernard, Prairie, MS, August 17, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers; Oberia Holliday to Jacqueline Bernard, Prairie, MS, September 13, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Jacqueline Bernard to Oberia Holliday, New York City, October 27, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Oberia Holliday to Jacqueline Bernard, Prairie, MS, December 12, 1966, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Oberia Holliday to Jacqueline Bernard, Prairie, MS, September 1, 1967, box 1, folder 2, Bernard Papers.

- Liberty House, “Prairie, 6/5/67,” and “Prairie, 3/29–30,” box 2, folder 20, PPC Records.

- Liberty House Newsletter no. 36, November 19, 1969, and “Meeting at Una Co-op,” August 1, 1970, box 2, folder 4, Doris Adelaide Derby Papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

- David Llorens, “Mississippi Revisited,” Ebony, July, 1969, 46–58.

- PPC Chart, January 27, 1968, box 2, folder 4, Derby Papers; Liberty House Newsletter no. 36, November 19, 1969, box 2, folder 4, Derby Papers.