“They drive by an old-timey church with one door for the men and a separate door for the women and a graveyard out back where the stones pop up like teeth in the night.”

When Charlie sings, her sister Audra’s voice follows, the voice of a grown woman inside a little-girl body, high and lonesome and worried at first, till it wraps itself around hers to become pure and whole, and then forks off on its own. They were raised first on shape notes at church and the radio and Who’s gonna shoe your pretty little feet, who’s gonna glove your hand? but what they like to sing best are the old, old ballads. Audra’s favorite is “Down from Dover” the way Dolly does it, and Charlie likes to sing the Everly Brothers, the lady “old and gray” pleading with the warden to get her baby out of jail, and they intertwine the closest when they chorus the Louvin Brothers, “go down, go down you Knoxville Girl.” Charlie’s voice is the current, low and silty and running over the trace fossils and the smoothed-over ancient stones and Audra’s is the steam rising off the water, eerie and sure, slipping off into sky and ether. They sing the songs their mother can hardly stand to hear now, the songs their daddy taught them.

The father isn’t the kind of television dad with a big white smile and a punchline or a picture-book daddy grilling hot dogs and pitching baseballs. He is the kind of father with handsome craters in his cheeks and the rocket end of a cigarette in his lips, the kind who comes home from somewhere you know better than to ask about with a hollow look in his eye like the black holes where stars get swallowed up. He is the kind of father liable to set to pacing the house as soon as the mother has driven off to work third shift and the exhaust from her old black Ranger has settled into the dirt, the kind to wake up the house in the blue hour when darkness is just coming on and drag Charlie and her sister out of their first dreaming, tell them to bring along the things they love ’cause they might not never see them ever again.

The last time it was their mama driving on the third or fourth day of him gone off somewhere and Charlie must have been carried out to the car in her sleep. She woke in the middle of the night to car doors slamming and lights from the parking lot streaming through the gap in the curtain on her mama and sister’s sleep-faces beside her, in a king-size bed with sheets washed hard and stiff as boards. The television was on home shopping, silent, and when Charlie stood up she stepped barefoot on a dried curl of an ancient fingernail stuck in the motel carpet from who knows how long ago. She froze, staring hard at the No Vacancy neon shining on the bright jaggedy carpet patterns, thinking about how you could never clean out all those strangers’ lives, how they were right here beside her in this room, always, inside those fibers, inside the asphalt and soil underneath.

In the morning she and Audra had cleaned out the complimentary powdered doughnuts by the reception desk and swum circles in the kidney-shaped pool in their underwear watching their mama twist her hair around her finger inside the smudgy window of a pay phone booth. She’d taught them at the rec center on summer mornings when they were little still and she was tired out and the father was home sleeping: how to backstroke and float, how to swim below the surface, how to breathe. Don’t you worry, she’d said. Then she leaned in and whispered to them each a secret before she let go.

They jumped out as soon as they saw her come out with her head down and her long hair swinging down her back and they drip-dried and put their nightdresses back on and sat still in the truck while their mother held the steering wheel with the blinkers flashing left out of the parking lot. Then all of a sudden she flipped them to the right and drove for a long time west as the swooping lines of the Blue Ridge chased alongside them and the treetops and turkey vultures flew overhead. She didn’t yell at them for dripping poolwater on her seats. She just said, Lord if they didn’t look exactly like little ghosts in those white cotton slips of theirs. Then she looked straight ahead at the long slanty road and said last night and this morning was their own little story and not to tell the father when they got back home.

He would find out. He always found out. But it would not be on account of them.

The father does not have a regular job anymore since the mine closed, since the paper mill shut down, since he got in a fight up at the furniture factory where their mother works the graveyard now, fitting together dresser drawers and building sofas in the middle of the night. Where the father goes and what he does for money is his own business. Once upon a time he too was a singer before he stopped.

Now the father drives them through the last of the purple twilight, just before everything turns gray and black and white. They pass the turnoff to the factory where the mother works, past the closed-up mines where the hills are scraped bald as the moon, and past a llama farm where in daylight you can see their long pale brown necks through the trees, and past a roadside stand with a spotlight to shine on thieves, selling dolls with withery scrunched-up faces made of dried apples, and past more roadside stands selling honey and guns. They drive by an old-timey church with one door for the men and a separate door for the women and a graveyard out back where the stones pop up like teeth in the night.

“When I grow up, I want to be a river,” Audra says and Charlie thinks of their mother, of the way her hair rains down her shoulders and along her back like a waterfall, the way some mornings tired after her shift she would sink into the sofa like the Lady of Shalott in her little boat in the painting Charlie got from the poster print sale at school. Back before the father slashed out the cushions with a hunting knife and the next day asked who had done such a thing.

Audra rolls down her window and leans her face out to feel the air from the cold spot she knows is coming around the next bend and she shrieks and shivers when it hits her and pops her head back inside laughing. The daddy laughs too. He says they are going places. He is all of a sudden in a good mood like he has a secret inside him. He shoots the car over the county line, drives them up and up a careening road that winds around and then stretches way out ahead like a spool of velvet rolling toward the stars. Charlie knows better than to ask if she will sleep in her own bed tonight, better than to ask if they will be back home by dawn when the mother’s shift is over. Audra is still young enough to get away with it. “Are we lost?” she says.

“Hell, no,” the father says. “Does it look like I’m lost?” There are streaks of dirt and sweat on his arms and clothes and a smell of the woods around him. His boots are caked with straw spilling all over the floorboard.

“Are we running away?”

“Now ain’t that some idea,” the father says. Charlie recognizes a shine in his eyes, a smile. He reaches behind in the backseat and claps Audra on the knee. “Ain’t you just full of ideas.”

THE FATHER FEELS LIKE he could drive all night. There is a new fire in his mouth, a hot orange glow turning quickly to smoke. He is already rolling his next cigarette with his free hand. Who knows. Maybe they’ll go all the way to Nashville, to Vegas, to Reno, to Hollywood. “But Mama? What about Mama?” Audra says.

“Oh, I’ll send her a limousine,” the father says, and Charlie shivers into another cold spot, picturing it, sleek and smoking like a train, flinging up dust down their long red road.

Audra wants him to tell them a story but the ones she likes best star her, and the ones the father tells all dart in tangents and pieces around them and return, as always, back to figure on him. About the two-and-a-half-foot longnose garfish that fell freakishly out of nowhere and onto the ground like a prehistoric warning. It had been on a night like this, the night before he met their mother. The next day at dusk he was walking through the weeds trying to find the switchback creek where as a child he’d escaped his own baptism. And there the mother was, leading her horse to drink. When he saw her far off at first he’d thought she was a deer; he raised his gun.

“Those aren’t stories, those are visions,” Charlie says. When he doesn’t tie any connection between them they rise up around her like moving pictures, like the tricks her mind makes in the darkness, inventing figures running past and strange faces in the grooves of the tree trunks, morphing a rope swing into a noose, the rope into a snake, coiled inside a tire, a forest of kudzu like a distant planet. Charlie had been saved in the creek that their father ran from, a white-hot summer day with the choir wet up to their knees in a semicircle singing “Are You Washed in the Blood” and the face of her mother standing in the shallows with Audra in her arms mouthing the verses and of her father walking up late behind her grinning on the shore like he was watching a horse race, the last thing she saw just before the preacher’s hand swooped down, cupped her head and plunged her below. She thrashed underneath the preacher’s palm.

It had been the preacher too whose arms pulled her up that afternoon but in the flash between the dunking and the lifting Charlie had seen her own white dress floating up to the clouds on the water’s surface. There was a quick cool stillness that wrapped its arms around her, that she knew she would always long to travel back to. She’d felt the reeds shifting below, and she swore she heard her sister’s song. And she rose to meet it.

The Mother does not or decides not to remember the father shouldering a gun that first afternoon, does not remember being a deer in his sights, but does remember a man who stepped out of the shadows at the water’s edge and helped her lead back to her boss’s barn the horse he’d startled, the new man in town who charmed her with his jokes and his lean good looks, the man she followed later that evening deep in the county to the Constant Stranger Lounge, where the father and his brother Clive sang Friday nights. These are the songs that are all around us, they said, seeping into the ground. They called themselves the Missing Pieces, introduced themselves as real-life descendants—great-great-great-great-grandsons of Charles Silver for whom Charlie would be named, killed by his wife Frankie. The first song they sung is the one that the newspapers claimed was Frankie’s confession; they printed it up just like a poem.

When Clive and the father were little, they said into the microphone, they dared each other to go outside at night, for surely they’d see Frankie herself walking out on the road with an ax in her hands and blood in her eyes. Still the ballad with Frankie’s name in the title leaves out the part where she told the judge she had to swing first before her husband could finish loading his gun.

They sang in a way that went all up and down the mother’s spine, each voice craning to find the other. The sounds they made didn’t match the gravelly, mumbling way they spoke, or how they stood—Clive, a big man sunburnt from work, looking fit to bust out of his suit and the father—a rakish, wily weed—but their voices ached and trilled, stretching out vowels into extra syllables of regret and anguish. When they did “Omie Wise,” the mother had to watch their mouths in the stage lights to pick out which brother was singing which piece. The father started the melody, and his brother moved in and joined him there, but then the father raced up and down the register like he was harmonizing with himself, like he was the killer and the drowning girl all at once.

And the mother told the girls how the father seemed to stare straight at her when he sang, how she couldn’t hardly help but fall for him then, how she also understood right off that she could never know him the way his brother did. Blood harmonies, she called it. They fought as hard to fill the spaces around the sound in each other’s voices as they did to kill that same emptiness. Awful, ugly brawling matches that set off sometimes as soon as the last note still hung in the air and dragged out onto broken bottles in the parking lot. Charlie was too young to remember Clive before he finally ran away from the father’s life for good, and she only knows the picture of them on the tape they saved up and made at a little recording studio over in Johnson City, the tape Audra and Charlie memorize on their boombox in the summertime woods, its plastic cover cracked, secret in Charlie’s sweatshirt pocket now as Audra makes a pillow of her lap, humming even as she closes her eyes.

When Clive disappeared, the mother told them, part of their daddy took off too, left behind the part doomed to retrace these roads each night, the one that points out to his daughters the far-off direction of the holler where he was born, where he and Clive walked from house to house on swinging bridges stringing together the steep, impossible shapes of the ridges. “Swaying and twisting in the wind. Black water rushing below our feet.”

The father swerves and Charlie thinks how if she has to jump out of the car she will push Audra out first and scream at her to roll. She will cut their hair short like Frankie Silver did when she broke out of jail, passing in men’s clothes, crouching in a hay wagon. They will have new names, names that don’t come from around here. But they’ll always sing for the old ones. When their mother took away her hand, she’d whispered, Don’t you be afraid to fall. The water will always lift you up.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer of fiction and nonfiction who grew up in western North Carolina and is currently based in Brooklyn. Her stories, interviews, essays, reported pieces, and collaborations with artists have been published in Aperture, the New York Times, the New Yorker, and the Paris Review. Her first book of essays, Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists, was published in 2023 as part of the Aperture Ideas series.

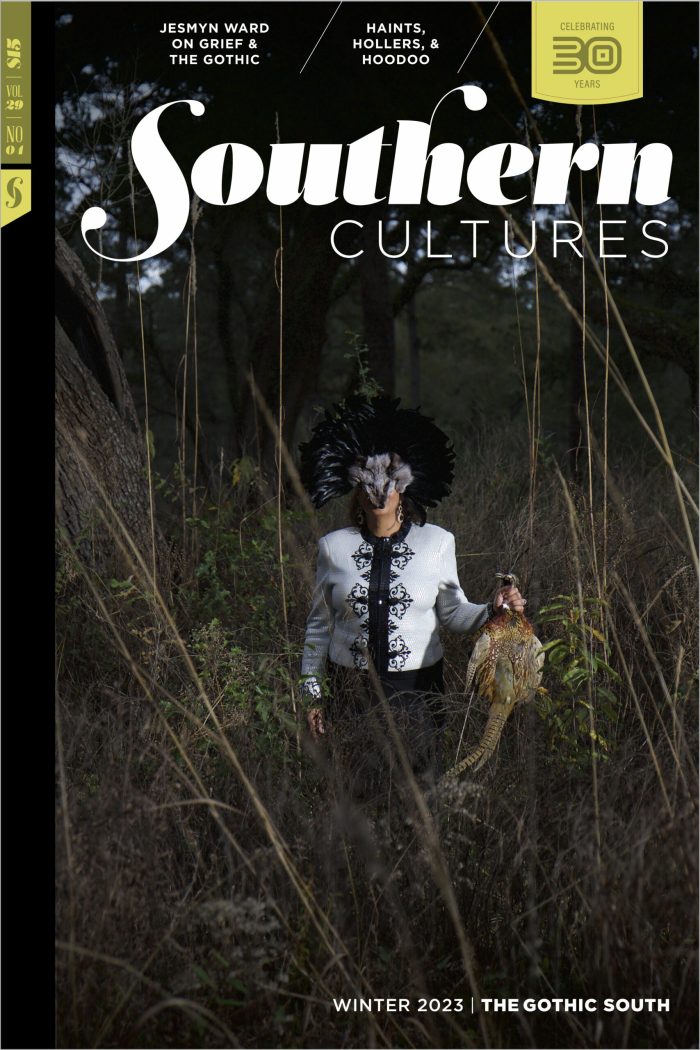

Kristine Potter is an artist based in Nashville. She holds an MFA in photography from Yale University (2005) and is the recipient of numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship (2018) and the Grand Prix Images Vevey (2019–2020). Potter’s first monograph, Manifest, was published in 2018, and her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and is held in numerous public and private collections, including the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and the Swiss Camera Museum, Vevey. Potter is currently an assistant professor of photography at Middle Tennessee State University.

Header image: Impasse at Sodom’s Creek, 2017.