On August 26, 1967, the Lads of Liverpool (a.k.a. the Beatles) yielded the no. 1 spot on Billboard’s pop chart to an unknown musician. Mississippian Bobbie Gentry’s iconic song, “Ode to Billie Joe,” remained in that space for four weeks. During that time, her audience latched onto what seemed to be a mystery in the song’s fourth verse that pushed sales well into the fall of 1967: “He said he saw a girl that looked a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge / And she and Billie Joe was throwing something off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” Fans across America wondered what Billie Joe and the female narrator threw off of the Tallahatchie Bridge, near Gentry’s hometown of Greenwood, Mississippi. But Gentry played coy when asked, telling one interviewer, “Everyone I meet has a different guess about what was thrown off the bridge—flowers, a ring, even a baby. Since I’ve been in Hollywood working, one person asked me if it was a draft card! Another wanted to know if they threw away a bottle of LSD pills. Like, weird!”1

Gentry’s refusal to affirm a single interpretation of the song was critical to its success. The most popular interpretations—throwing a fetus off of the bridge, for example, more common in the twenty-first century—were feasible because ambiguity and implication, the precise qualities that spurred the song to iconic status, were prime elements of respectability in the post–World War II era. As historian Beth Bailey argues, “A great many Americans saw respectable behavior as the foundation of a moral, civil and legitimate social order. And a great many Americans saw respectability as the . . . price of admission to the expanding American middle class.” In the South, as the GI Bill helped forge a new suburban geography, respectability politics in small towns like Greenwood required silences to hide what might contradict a segregated society with clear boundaries between public and private spaces, and with different behavioral standards, morals, and realities.2

Publicly, “respectable people” were white, Christian women who maintained good homes, cleaned by Black working-class women, or white men who worked middle-class jobs while their Black counterparts raised cotton and other crops as sharecroppers. In private, however, in the hints and whispers between image and reality, the not so subtle reminder that, if you were Black, you could not be respectable, no matter your status, profession, or wealth, put the lie to the image of respectability. And, if you stepped out of your place, violence could be used to remind you where you belonged. In this context, in the South, where bridges and water were emblematic of racialized violence against Black men, southerners—and perhaps Mississippians in particular—might have drawn other conclusions: that the song’s protagonists threw a Black male body off the Tallahatchie Bridge.3

The musicianship and lyrics certainly make this interpretation possible, but the implications were made even stronger once the full promotional arm of Capitol Records produced videos of Gentry walking on the Tallahatchie Bridge near Money, Mississippi. Articles about Gentry and “Ode to Billie Joe” then appeared in Life magazine and were featured on the bbc, which captioned photos and video of her as taken in Money. Nowhere, however, did the publicity remind, at least explicitly, her nonsouthern audience of Money’s lynching victim, Emmett Till, who was brutally murdered and thrown into the Tallahatchie River in 1955 after he was accused of challenging a white woman’s respectability by whistling at or flirting with her in her store.4

But true to respectability’s ability to dodge and weave, to imply rather than state, the possibility can only be suggested, rather than confirmed. And that is the point: it is the autobiographical context that Gentry relied on that matters here, not whether one particular interpretation is the “correct” one. Multiple interpretations are possible precisely because she mined her past and its roots in 1950s respectability politics, which catered to white southerners. The song’s inherent mystery is thus a function of 1950s southern politics as much as a fanciful story about one man’s suicide. In fact, one could claim that Carolyn Bryant, the white woman who alleged that Till whistled at her—she later recanted the allegation—utilized the same fictions as Gentry to shore up her own racial and class status.

In many ways, then, “Ode to Billie Joe,” the third-bestselling single of 1967, was Gentry’s musical autobiography of Money and Greenwood (both in Leflore County), a compendium of local social and musical practices, vaguely rendered for a national audience. This autobiography accounted for southern suburbanization and a new racial politics that recognized some civil rights gains. It matters that this was done musically, too, since Mississippi and other southern states sell themselves as the birthplace of American music. Pop music thus became an important site for political work in 1967 for Gentry and other southern musicians like Elvis Presley and Tammy Wynette.5

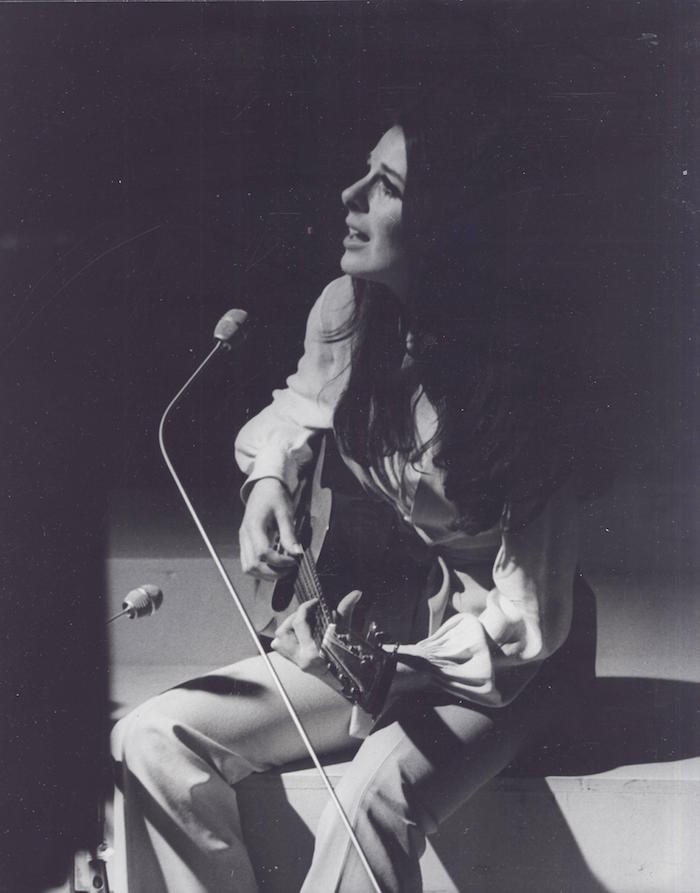

The mysteries associated with “Ode to Billie Joe” begin with its original production. Gentry moved to California in 1957 from Greenwood, later received some college music training, and was actively writing, recording, and performing when she brought two complete demos to Capitol Records in the spring of 1967. The song “Mississippi Delta” was initially the A-side cut, “Ode to Billie Joe” the B-side. Where she recorded them is unclear, but she appealed to Capitol staff producers who were looking for musicians with regional-sounding tunes. Gentry’s work also came just as Aretha Franklin’s powerful soul music was racing up various musical charts and as Franklin appeared on the cover of Time magazine as “The Sound of Soul.” White female blues singers with a vocal timbre like Franklin’s, according to scholar James Barton, were starting to find some success in her wake. Janis Joplin was the most obvious example, thrilling a Monterey Pop Festival crowd in June 1967 with a raucous rendition of Big Mama Thornton’s “Ball and Chain,” a performance that landed her on the cover of Newsweek soon after.6

The song “Ode to Billie Joe” needed some minor production work—namely, the addition of strings—before its release on July 10, 1967, during the Summer of Love (it came out two days before the Newark riots). Its almost instant popularity caused Capitol Records to rush Gentry back into the studio to record an entire album, titled the same, released on August 22, 1967. The record’s song list reflected her initial demos, with “Mississippi Delta” as the opening track and “Ode to Billie Joe” as its final. Lyrically, the intervening tunes were miniautobiographies of the Delta, with references to southern foods, local bugs, and going to town on Saturday. Indeed, as journalist Holly George-Warren has observed, Gentry mined her upbringing in Mississippi for her first two albums. Musically, however, the majority of the first album’s songs were rehashes of “Ode to Billie Joe.” Capitol hurried the album’s design work, touting Gentry as a country girl, demurely dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt, in front of a lush green background. The record company then leveraged the single’s success by sending her out on a publicity tour that linked her closely to Greenwood and its surrounds.7

Gentry incorporated some standard blues practices into the song, like the harmonic I-IV-V chord structure that bluesmen like Robert Johnson used. (His gravesite is rumored to be a few miles north of Greenwood on Money Road.) She also used seventh chords in a manner associated almost exclusively with blues music, in which the nonfunctioning chords “float,” meaning they do not resolve. “Ode to Billie Joe” relied on D7 and G7, with a C7 thrown in on the last verse. But Gentry also used a bossa nova beat—a Brazilian rhythm that likely inspired multiple jazz covers of the song, including one by saxophonist King Curtis that rose higher on the Billboard R&B charts (charts that largely measured Black audiences’ consumer patterns) than Gentry’s did, hitting no. 6 the same week Gentry’s version hit no. 8.8

Gentry tapped into white lyrical traditions as she incorporated country music’s standard for telling three-minute song stories. “Ode to Billie Joe” is at its base a good story with a beginning, middle, and end. But country music audiences, majority white, avoided Gentry’s version at first, buying instead country music singer Margie Singleton’s cover, released soon after Gentry’s was released. Singleton’s cover eliminated some of the more “exotic” elements such as the bossa nova rhythm and the seventh chords. She also added a drum and dobro as well as a country shuffle (drum) beat, making the song a better fit for a country audience. Singleton’s cover also initially rose higher than Gentry’s on the country music singles chart, rising to no. 39 the same week Gentry hit no. 40. However, the album Ode to Billie Joe eventually reached no. 1 on the country music record charts.9

Even as the various ad campaigns highlighted the lyrics as country ones (and therefore white), Capitol Records drew out the obvious Greenwood references, in particular, making sure the Tallahatchie Bridge was always in front of Gentry’s audiences. An August 19, 1967 Billboard ad featured Gentry with the line “billie joe [sic] jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” The Life magazine photos and the bbc’s production of a music video shot on the Tallahatchie Bridge in Money were part of the marketing package. Appealing to a crossover audience, Gentry’s publicity team also touted her appearances on integrated live shows. Billboard announced in early September 1967, for example, that she was appearing on a regional R&B television show with B. J. Thomas, the O’Jays, and Jackie Wilson. Black Cleveland DJ Ken Hawkins hosted the program, promising that future shows would be integrated with white dancers.10

The song’s musical elements, along with the publicity from Capitol, fooled radio program directors who clamored for pictures of Gentry because they could not tell if she was white or Black. Gentry initially hid from cameras so that disc jockeys, who used a musician’s race to determine whether they played her music to Black or white audiences, would present her crossgenre, a smart move that allowed her to build an interracial audience. In the interim, she asserted, “I don’t sing white or colored. I sing Southern.”11

Gentry moved to Greenwood at age five (approximately 1947) to live with her father and stepmother, and to attend school in Greenwood. At the time, Greenwood was a small Delta town of fifteen thousand, and more than half of its residents were Black (Leflore County had an even larger Black population). The core economy in the 1940s and 1950s was cotton. Geographically, the Little Tallahatchie, the Yazoo, and the Yalobusha rivers seemed to simultaneously split the town in two and mark its external boundaries. The rivers were also sites of racial violence. Acknowledging this, lawyer J. J. Breland, who defended the men who murdered Emmett Till, said, “If any more pressure is put on us, the Tallahatchie River won’t hold all the n—— that’ll be thrown in it,” a direct reference to the violence used against those who challenged Jim Crow.12

When Gentry moved to Greenwood, the family lived in the relatively integrated downtown near a vibrant blues music scene, now part of the Mississippi Blues Heritage Trail. After serving in the Signal Corps during World War II, her father, Robert Streeter, opened a radio sales and repair shop next door to the family’s rented house on Lamar Street. Blues guitarist Furry Lewis was born on Lamar Street near Baptist Town, an African American section of Greenwood with a vibrant blues scene where bluesmen Robert Johnson, Honeyboy Edwards, and Tommy McClennan all performed, albeit not during the time when Gentry lived on the street. Streeter’s radio business meant Gentry could hear more than the music of local musicians. She listened to shows like King Biscuit Time, out of Helena, Arkansas, which featured blues artists like Ike Turner. Radio crossed racial lines with impunity, sending new sounds into the living rooms across Mississippi and beyond to those willing to tune in.13

Lamar Street remained interracial, but the GI Bill of Rights, passed in 1944, funded new possibilities for white soldiers to pursue life in postwar era suburbs, one that came to be linked symbolically and physically to a modernized version of racial segregation. While Black soldiers could access GI Bill funds, unethical banking practices kept many from purchasing homes. Both formal and informal racial covenants, though declared illegal in Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948, stalled Black purchases of new suburban homes in the South. Newly fabricated homes, financed by the GI Bill, became the outward expression of a respectable family, an unspoken value ascribed to upwardly mobile white families. But it was a public image that hid a vast array of private wrongs, where anger and violence could hide under a smooth public veneer and behind closed doors. This space between public and private in part allowed “Ode to Billie Joe” its cryptic meanings.14

The Streeters, likely using Robert’s GI benefits, bought a house at 815 Claiborne Street, north of the Yazoo River, in 1951 or 1952, in what was Greenwood’s newly built, exclusively white, middle-class suburb. In doing so, they distanced themselves from their more integrated neighborhood (Streeter moved his business, too), surrounding themselves with other white southerners, some of them also World War II veterans. Among their new neighbors some blocks away, for example, was Byron de la Beckwith, the former marine who assassinated Medgar Evers, the state field secretary of the NAACP, in 1963.15

Racial exclusivity might have been expected to close off interracial musical exchanges, but it did not. In fact, the area’s economic and Jim Crow systems provided spaces for Black and white southerners to share music. The GI Bill funded new housing developments, making segregation seem natural in the world of fine ranch homes and new consumer commodities like televisions, but respectable white southerners required working-class Black men and women to toil in cotton fields or clean those homes. Employing Black women as maids was a status symbol for these suburban white women, who continued to control Black working-class women’s labor. Edith Slaughter Streeter, Gentry’s stepmother, might herself have needed this labor, given that she had four children to raise, though this is unclear.16

In the county, cotton farming remained the basis of an economy that allowed white men like Streeter to move into nonagricultural jobs while tying Black men firmly to the land; by 1950, nearly 90 percent of Leflore County’s land area was farms. But music was in the fields, too. One local Black woman, Elizabeth Pitts, who was a plantation worker in Leflore County in this era, recalled those chopping or picking cotton making music: “Some of them be singing out in the field, I used to hear singing. Men, you could hear them singing, plowing behind the mule.” As Pitts notes, it was possible to encounter music in unexpected places in Leflore County.17

In the city, churches doubled as performance stages when secular ones did not exist. Gentry learned some of her music in white churches. And she heard Black residents, too, who performed at public musical venues like front porch parties where singing together was the main entertainment. One resident, Sadie Hammond, recalled, “Lots of times we’d have singing at different homes. Sometimes we’d be sitting out on the porch, people would be stopping by, we’d sing and have a good time. Then again on Wednesday night we’d have a prayer meeting at someone’s house.”18

In the county, there were Black-owned cafés, or “places” (another word for a juke joint), that sold homemade moonshine and food, and featured local blues musicians. Cafés provided an alternative source of income for sharecroppers. Leflore County resident Bernice Magruder White remembered that her father had

[A] room built onto his house and he had a piano and he would hire a piano player. Every Saturday night, they would come and they would dance and play the piano. This little room was off kind of like, we couldn’t go in there, not even during the weekdays. It was always locked till on weekends. And, of course, maybe two or three miles over somebody else would have one very similar, and they did the same thing. So that’s how they were entertained in the rural area before people could get to town. It was a hardship getting to town.

Black church members eschewed “places” because, to them, they promoted immoral behavior, including bad language. Sadie Hammond recalled, “Every night they’d have their dance somewhere. Fiddling and dancing and drinking whiskey. And cussing too, they say. They tell me they be cussing. Uh huh . . . but I never did go. If I’d ever go, mama would’ve beat me to death.”19

The rare white man might show up at one of these places, but rigid notions of racial purity meant that white women were strictly excluded. Black women, on the other hand, because of the strong tradition of Black female musicianship, were welcomed—and sometimes owners themselves. Referencing that Black female musicianship, resident Georgia Denton Bays remembered the lure of her aunt’s guitar. One day, her mother called out,

Go get me some water. I said, “Mama, wait a minute.” My auntie had a guitar and I was in there playing that guitar. “Georgia, come get that water so I can finish your daddy’s dinner. He’ll be here directly.” “All right, Mama.” Before I knowed anything, Mama got there, had a switch just about that long, and come in there, and that guitar went up in the side of the wall and everything.20

But even the most positive public musical exchanges that crossed racial lines could not mitigate the significant tensions that emerged in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in May of 1954, a decision that challenged the foundations of white racial power, in particular the all-white schools that educated southern children. Aggrieved white southerners called it “Black Monday” and white politicians politicized white elementary and high schools, locating them as sites of white racial power under attack by nefarious forces like the Supreme Court. The decision provoked racists like de la Beckwith to claim that the naacp sought to “put a negro in your daughters [sic] bedroom as the master and ruler of a mulatto family,” again positing even the most basic racial accommodation as a threat to white female purity.21

The Brown decision also catalyzed the founding of the White Citizens’ Council (WCC), a white supremacist middle-class organization devoted to maintaining Jim Crow segregation, in next-door Sunflower County in July 1954. Brooks Brothers suits and artfully designed homes, key symbols of respectability, masked a virulent masculinity bent on protecting an idealized and symbolic white womanhood from the imagined threat posed by Black men—in this case, young Black boys attending school with white girls. The WCC helped to modernize the southern rape myth and root it in these new notions of respectability. The myth, a trope created in the 1890s, leveraged threats of violence, specifically lynching, when white southern men were faced with insurgent Black power in that era. (Bridges were especially prominent in this iconography.) As the White Citizens’ Council reformed the myth to fit 1950s Mississippi, it required a new incarnation of white women to follow its updated views on race and masculinity. Where she was once a fair flower of southern womanhood in the late 1800s, in the 1950s, she was a southern June Cleaver, of Leave it to Beaver television fame, a white woman who kept house, raised children and did charity projects on the side, all the while supporting her husband in his work.22

Greenwood citizens were prominent in the White Citizens’ Council, and two of its citizens sat on the council’s statewide educational board as the organization spread quickly. By 1956, it claimed eighty thousand Mississippi members, with chapters in nine other states. The organization’s recruiting language promised the fine folks in the North that racial control was still appropriate in this era of respectability. The middle class used different means, or at least so they said, to control Black behavior. They did not (supposedly) use violence, for example, touting in council-produced pamphlets, “After all, we’re not the Klan.”23

The WCC’s focus on the Brown decisions was more than remaking gender and racial boundaries under supposed attack. Labor control still mattered because cotton did not get chopped and June Cleaver’s fine suburban home did not get cleaned without a large Black labor force of all ages. The Brown decisions thus challenged not only racial and gender practices but also local labor practices because the Brown decision assumed that Black kids should go to school (and good ones at that)—and eventually leave behind grueling farmwork and poverty altogether for new lives. It was in this tense time that the Streeters’ move across the river required Gentry to attend the North Greenwood Elementary School (now the Katherine Bankston Elementary School, named for her principal in the 1950s).24

Whites perpetrated acts of violence against Black residents in the city and county, illustrating the intimate, symbiotic link between Greenwood—where cotton sales dominated the local economy—and Leflore County, where that cotton was grown. Booker T. Federick, a local Black man, said, “Now, I’ve heard of them drowning people. That happened back in the fifties here in town . . . A young man wasn’t drowned here in this lake, but up the road over yonder in the river. But the things that they put on him that may keep him from coming up and make sure he drowned, those weights and things come from here in town.” Although it is not clear, Federick was most likely speaking of Emmett Till, though two Black men from the area had been killed in 1955 as well. Numbers illustrate Leflore County’s and neighboring Carroll County’s grim reputations as places notorious in the history of racial terror violence, with Leflore County having the highest number of confirmed lynchings in the state of Mississippi at forty-eight. (Carroll County had twenty-nine, the second highest.) Mississippi was also the state with the highest number of lynchings in the country (654 confirmed).25

These musical and racial practices are implied in the autobiographical lyrics of “Ode to Billie Joe,” a nostalgic tale of Gentry’s upbringing in Leflore County. The song—and the quaint rural life depicted in its publicity—seems ignorant of the labor and the violence that shored up white suburbia, until the fourth verse, when the narrator and Billie Joe throw something off of the Tallahatchie Bridge (a baby? another body?), and in the repeated sixth stanza, where Billie Joe jumps off of it himself. In those repetitive lyrics, Gentry hints at but never explicitly shares the darker sides of respectability.

The lyrics recreate the Delta through a common daily ritual: the white nuclear family’s break from fieldwork to eat the midday meal, rendered in nostalgic terms because respectable folks like the Streeters no longer picked cotton in an era where, census records document, just a few white women still worked in the fields. A southern vernacular and sound dominate the lyrics: “y’all” rather than “you all”; the word “was” used for plural nouns. Southern food staples are also prominent (black-eyed peas, biscuits) as Gentry describes the noon dinner break:

It was the 3rd of June, another sleepy, dusty, Delta day

I was out choppin’ cotton and my brother was bailin’ hay

And at dinner time, we stopped and walked back to the house to eat

And mama hollered out the back door, “Y’all remember to wipe your feet.”Papa said to mama as he passed around the black-eyed peas,

“Well, Billie Joe never had a lick of sense. Pass the biscuits please.

There’s five more acres in the lower forty I got to plow.”

And mama said, “It was a shame about Billie Joe anyhow.”

In each of the stanzas, the iconic and repetitive fifth and sixth lines then announce Billie Joe’s suicide from the Tallahatchie Bridge.26

What is intriguing about the song is its quotidian nature, rooted in respectability’s ambiguities, as well as its ability to capture this daily rural scene and bury the commonness of a Delta June day—“pass the biscuits, please”—within the passing along of extraordinary news in Billie Joe’s suicide. This is Gentry’s true gift, at least lyrically: the ability to capture the ordinariness of the South. And it is in that ordinariness that makes this song the autobiography of this place, this people and their racial politics, purporting to be common, but perhaps not so much, in Gentry’s hands. It remains difficult to pin down her precise meanings, however, since Gentry refused (in the 1960s) to confirm one interpretation over another. By leaving room for multiple interpretations, she allowed that her multiracial audience would continue to find a variety of meanings in the song.

The most obvious ambiguity is what was thrown off the bridge in the fourth verse—the verse that catalyzed the national guessing game. A common guess, both in the 1960s and present day, is that the pair threw the body of an infant over the edge, the child born of an illicit sexual relationship between the narrator and Billie Joe. But the Capitol Records publicity team used local Leflore County landmarks, in particular photographing Gentry walking along the Tallahatchie River in Money, Mississippi. Here’s where the musical autobiography potentially turns more precisely into a biography of Greenwood’s racial practices. Crossing the Ashwood Bridge, near Gentry’s elementary school, out into the county, Money, Mississippi, is a mere ten miles north of where Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old black boy from Chicago, was murdered by two local white men in August 1955. Gentry was only a year younger than Till when he was killed. Till’s story is typically told this way: coming on the heels of the Brown v. Topeka decision which so angered white Mississippians that a local circuit judge believed that killing young Black boys would be necessary, even unavoidable, Till supposedly whistled at or said “bye, baby” to a local white storeowner’s wife, Carolyn Bryant. We know now, based on a 2007 interview with historian Tim Tyson, that Carolyn Bryant lied about the circumstances of that encounter. But in her view and that of her husband’s and brother-in-law’s, Till did not acknowledge her status as a respectable white woman and had to be punished.27

We do know what happened next to Till because the murderers gave an interview to Look magazine after their acquittal by an all-white jury. They kidnapped Till from his uncle’s house, savagely murdered him, and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River where it was found floating in Tallahatchie County three days later. His mother Mamie Till then had an open casket funeral in Chicago so the whole world could see what they had done to her son. Ebony and Jet magazines published photos of his mutilated body in its coffin, helping to ignite the Civil Rights Movement.28

The ordinariness of this violence and its use to affirm the white nuclear family is embedded in “Ode to Billie Joe,” with cotton being chopped and hay being baled and human beings thrown off of bridges, too. Respectability necessitated that violence, albeit whispered and hinted at, was built on the subtle suggestion to Black southerners to behave or there might be a bridge in their future.29

But “Ode to Billie Joe” also reflects civil rights actions taken in Mississippi and elsewhere, at least insofar as it attracted a Black audience that pushed it up near the top of the R&B chart. A generation of Black southerners watched the Till trial and saw examples of brave testimony against the murderers as well as at the murderers’ acquittal. After the acquittal, white Mississippians declared themselves “vindicated,” in that the all-white, all-male jurors had “fairly” come to their decision despite significant pressure from “outsiders.” If some white Mississippians felt otherwise, there was little room to express it, at least publicly. This was the silence that respectability exacted. For white men and women, expressing guilt or sadness was potentially costly. Many expressed righteousness at the verdict because the violence that murdered Till was also a threat leveraged against them if they disagreed. Even native son William Faulkner, whose work exposed the state’s complex and contradictory racial hierarchies, told a French reporter a few months after the verdict, “The Till boy got himself into a fix and he almost got what he deserved.”30

That Till generation, which followed the trial of his murderers and his public funeral, then became essential in making “Ode to Billie Joe” popular, called out white respectability’s basis in lynching and other acts of violence. In other words, the song became possible after that generation of Black children—including Gentry’s fellow Mississippian and civil rights activist Anne Moody—posed their own challenges to the South’s racial structures vis-à-vis sit-ins, voter registration drives, and boycotts. Indeed, the Civil Rights Movement can be understood as the context out of which Gentry’s song arose. If throwing Black bodies off of bridges had once been normal, the Civil Rights Movement now said those who perpetrated these crimes were criminals to be prosecuted and punished. The iconic fifth and sixth stanzas—where Billie Joe’s suicide is repeatedly addressed—can be read as a reaction to these cultural shifts. Read in these terms, Billie Joe committed suicide because vindicationno longer the only public expression available to white people; expressions of guilt were now also culturally sanctioned. As white respectability politics required violence to maintain the status quo, civil rights respectability politics required that violence be punished. With a protagonist coded white, Bobbie Gentry fashioned her unique answer between these two opposing poles, with obvious financial success.31

Every year, on June 3, some local radio program or celebrity celebrates the song’s fictional anniversary. The irony of the song, of course, is that Bobbie Gentry was raised up in a time and place where her schools symbolized the outrageous potential of race-mixing to white southerners, at least according to the White Citizens’ Council, even as they served as a symbol of respectable, white middle-class families. She then went on to write a song that drew on both Black and white musical and oral idioms, cushioned them in musical tropes from multiple musical forms, and created new ambiguous cultural spaces for a variety of postwar issues. In the end, however, we do not know why Billie Joe jumped off the bridge and that was precisely Gentry’s point. As listeners have long observed, the song’s fascination lies in the possibilities that it raises and refuses to resolve.32

Kristine M. McCusker is a professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University. She has published Lonesome Cowgirls and Honky-Tonk Angels: The Women of Barn Dance Radio (Illinois, 2008) and co-edited, A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Country Music (Mississippi, 2004) and Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (Mississippi, 2016), which was given an honorable mention as Best Book of the Year by No Depression magazine.

Header image: Bobbie Gentry Historic Marker & Tallahatchie River Bridge, by Jimmy Emerson, DVM, July 5, 2020. Flickr Creative Commons, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- “Ode to Billie Joe,” track 10 on Bobbie Gentry, Ode to Billie Joe, Capitol Records, T 2830, 1967, 33⅓ rpm; Billboard 79, no. 34 (August 26, 1967), Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University; “Bobby [sic] Gentry Has a Secret,” TV Week, Week of Nov. 26–Dec. 2, 1967, p. 19, folder 22, Bobbie Gentry Clippings, Archives and Special Collection, University of Mississippi, Oxford (hereafter cited as Gentry Collection); Tara Murtha, Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 68–69; Bobby [sic] Gentry, “Ode to Billy [sic] Joe – Bobbie Gentry (BBC Live 1968),” BarnstoneworthTown, August 7, 2011, YouTube video, 4:45, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaRacIzZSPo&list=RDHaRacIzZSPo.

- Beth Bailey, “Patsy Cline and the Problem of Respectability,” in Sweet Dreams: The World of Patsy Cline, ed. Warren R. Hofstra (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 67–85.

- For discussions on high pregnancy rates in the 1950s, see Rickie Solinger, Wake Up Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race before Roe V. Wade (New York: Routledge, 2000).

- Bob Dylan, “Bob Dylan – Death of Emmett Till,” Alf, July 4, 2011, YouTube video, 7:08, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVKTx9YlKls; Christopher Metress, ed., The Lynching of Emmett Till: A Documentary Narrative (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 318; Timothy B. Tyson, The Blood of Emmett Till (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017); Ruth Feldstein, “‘I Wanted the Whole World to See’: Race, Gender, and Constructions of Motherhood in the Death of Emmett Till,” in Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945–1960, ed. Joanne Meyerowitz (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994), 263–303; Michael Bertrand, “‘This Ain’t No Vaudeville!’ or Was It? The Shared Stage of Civil Rights, Politics, and Popular Music in the Post–World War American South” (paper, Southern Historical Association, Birmingham, AL, November 9, 2018). For research that examines bridges as sites of racial violence, see Jason Morgan Ward, Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 3; “Hippies Are Shifting the Value Structure,” Tennessee, July 19, 1967, p. 11, Nashville Public Library, Nashville, TN.

- Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 59, 17, 49–57; Cover, Time magazine, Time, June 28, 1968, accessed April 19, 2018, http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19680628,00.html; James Barton, “Earth Mothers, Backwoods, Women, and Jaded Virgins: Tracy Nelson, Dianne Davidson, and Marshall Chapman in Nashville in the 1970s” (paper, International Country Music Conference, Nashville, TN, June 3, 2017).

- “Bobbie Gentry’s Mercurial Rise Typifies Capitol’s Operation,” Billboard, September 15, 1967, https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Music/Billboard-Index/IDX/1967/Billboard%201967-09-16-OCR-Page-0068.pdf#search=%22bobbie%20gentry%22; Holly George-Warren, “Mystery Girl: The Forgotten Artistry of Bobbie Gentry,” in Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music, ed. Eric Weisbard (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 122, 126; Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 71–73.

- Mississippi Blues Heritage Trail sign for Robert Johnson, Mississippi Blues Trail, accessed February 8, 2018, http://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/robert-johnson-gravesite; R&B Charts for Billboard, October 21, 1967, https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Music/Billboard-Index/IDX/1967/Billboard%201967-10-21-OCR-Page-0044.pdf#search=%22bobbie%20gentry%22. Gentry’s use of acoustic guitars could also be reminiscent of Delta blues guitar players like Johnson who used them in an area where electricity was hard to come by. Gentry differed substantially from Johnson, however. He played with an open tuning in A whereas she tuned her guitar, a ¾ Martin called a Terz, in standard EADGBE.

- Country Music Charts for Billboard, October 28, 1967, https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Music/Billboard-Index/IDX/1967/Billboard%201967-10-28-OCR-Page-0064.pdf#search=%22bobbie%20gentry%22.

- “Down Home with Bobbie Gentry,” Life, November 10, 1967, p. 101, Gentry Collection; Gentry, “Ode to Billie Joe”; Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 71–87; ad, Billboard, August 19, 1967, https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Music/Billboard-Index/IDX/1967/Billboard%201967-08-19-OCR-Page-0017.pdf#search=%22bobbie%20gentry%22. Special thanks to Dr. Gregory Reish and Dr. Joseph Morgan for their substantial help (and good ears) in this section. Information about Ken Hawkins can be found at “Ken Hawkins,” Cleveland Association of Broadcasters, accessed August 9, 2018, http://www.cabcleveland.com/index.php?page=Ken-Hawkins; and “R&B TV Show Bows on WEWS, Cleveland,” Billboard, September 2, 1967, https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Music/Billboard-Index/IDX/1967/Billboard%201967-09-02-OCR-Page-0032.pdf#search=%22r%20b%20tv%20show%20bows%20on%20wews%20cleveland%22.

- Robert Windeler, “Song Is Southern but the Message Is Universal: Bobbie Gentry Reaches Top with ‘Ballad of Billy Joe’ [sic],” New York Times, August 23, 1967, quoted in Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 67, 70 (for quote), 74.

- Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 106. Contemporary PR campaigns state that Gentry was born in 1944. However, Gentry appeared in a Palm Springs newspaper clipping from March 10, 1960, in which she is described as the seventeen-year-old Roberta Lee Meyers (her stepfather’s last name). Because Gentry’s birthday is in July, her birth year is probably 1942. Fan sites generally accept the 1942 date as correct. Biography, Bobbie Gentry, accessed November 13, 2018, http://bobbiegentry.org.uk/biography/; Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 23, 25, 30, age 30 (photo clipping). In 1950, the rural population of Leflore County was 33,752 with 18,061 people residing in the city of Greenwood. “Number of Inhabitants, Mississippi,” 1950 Census of Population: Volume 1. Number of Inhabitants, US Census Bureau, accessed April 16, 2021, pp. 24–28, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1950/population-volume-1/vol-01-27.pdf.

- Robert Palmer, Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), 177–178, 206; Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 98; Donny Whitehead and Mary Carol Miller, Greenwood (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2009), 7, 9; Robert Harrison Streeter Sr., Find A Grave, accessed March 21, 2017, https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=35413370; 1950–1951 Greenwood City Directory, Greenwood-Leflore County Library, Greenwood, Mississippi. See also Blues Heritage Trail signs for Furry Lewis and Baptist Town, accessed November 15, 2017, http://msbluestrail.org/; The Story of Greenwood, Mississippi, recorded and produced by Guy Carawan, Folkways Records, FD 5593, 1965, 33⅓ rpm.

- Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Feldstein, “‘I Wanted the Whole World to See.’”

- 1954 Greenwood City Directory, Greenwood-Leflore County Library; Letter, Byron de la Beckwith, 331 W. Monroe, Greenwood, MS., to All Wholesale Distributors of Cigarettes in Mississippi and All Other States, July 1956, in the private collection of Kenneth Hensley, in author’s possession.

- Mandie Moore Johnson, interview by Doris Dixon, August 4, 1995, Behind the Veil Collection, Duke University Libraries, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil_btvct03030/ (hereafter cited as BTV); Edith Slaughter Streeter, Find A Grace, accessed April 6, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/177929970/edith-streeter.

- Elizabeth Pitts, interview by Mausiki S. Scales, July 24, 1995, BTV, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil_btvct04037/; Ray Hurley, Agriculture Division, Mississippi Counties and State Economic Areas (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1952), 1:22; “Operators: Censuses of 1950 and 1945—Continued,” in Chapter B: Statistics for Counties, 59, 68–69, http://lib-usda-05.serverfarm.cornell.edu/usda/AgCensusImages/1950/01/22/1801/28534800v1p22_Ch3.pdf.

- Kristine M. McCusker, “Funeral Music and the Transformation of Southern Musical and Religious Cultures, 1935–1945,” American Music 30, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 426–452; Sadie Hammond to Paul Ortiz, August 4, 1995, BTV, box MT5, Duke University Libraries.

- Bernice Magruder White, interview by Paul Ortiz, August 10, 1995, BTV, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil_btvct04134/; Hammond, interview.

- Brian Dempsey, “Refuse to Fold: Blues Heritage Tourism and the Mississippi Delta,” (PhD diss., Middle Tennessee State University, 2009); Georgia Denton Bays, interview by Doris Dixon, August 1, 1995, BTV, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil_btvct03029/.

- J. Todd Moye, Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945–1986 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 48–51; de la Beckwith to All Wholesale Distributors of Cigarettes.

- Ward, Hanging Bridge; Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). The Brooks Brothers reference comes partly from a Lillian Smith quote in Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 97.

- Moye, Let the People Decide, prologue, 66–69.

- Mississippi Country Music Trail marker for Gentry, Mississippi Country Music Trail, accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.mscountrymusictrail.org/markers/bobbie-gentry. Gentry’s blues sign is appended to Booker T. “Bukka” White’s sign in Chickasaw County. See Mississippi Blues Heritage Trail marker for White: “Bukka White,” Mississippi Blues Trail, accessed August 8, 2018, http://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/bukka-white.

- Booker T. Federick to Mausiki S. Scales, August 2, 1995, BTV, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil_btvct03034/; Jason Morgan Ward, “‘A Monument to Judge Lynch’: Racial Violence, Symbolic Death, and Black Resistance in Jim Crow Mississippi” in Death and the American South, Cambridge Studies on the American South, ed. Craig Thompson Friend and Lorri Glover (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 229–230; Moye, Let the People Decide; Lisa D. Cook, Trevon D. Logan, and John M. Parman, “Racial Segregation and Southern Lynching” (working paper 23813, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, September 2017), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23813/w23813.pdf; Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 3rd ed. (2017), tables 5 and 6, accessed April 29, 2021, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/; “Mississippi,” Lynching in America, accessed April 29, 2021, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore/mississippi.

- Gentry, “Ode to Billie Joe.” Searches through the 1940 Census for Leflore County in its first enumeration district show very few white women listed as sharecroppers, although they did exist. When they do, they are listed as “laborers” and their husbands, typically, as sharecroppers. 1940 census, Leflore County, MS., Enumeration District 42-1, pp. 6, 13, 22, 23, Ancestry.com.

- Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 76–77; Jerry Mitchell, “Emmett Till’s Accuser Admits She Lied. Now His Family Wants the Truth,” USA Today, February 9, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/02/09/emmett-till-family-wants-truth-accuser-lies/97683096/.

- Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 76–77; Feldstein, “‘I Wanted the Whole World to See.’”

- Gentry, “Ode to Billie Joe.”

- Tyson, Blood of Emmett Till, 185. Gentry at times has been described in terms similar to Faulkner in that her work is a musical take on the Southern Gothic tale, a format for which Faulkner was well known. Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” xiii.

- Misti Harper, “‘She Was . . . Haughty’: The Failure of Respectability Politics for Middle-Class Black Womanhood at Little Rock High School [sic],” (paper, Southern Historical Association, Birmingham, AL, November 9, 2018); Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi: The Classic Autobiography of Growing Up Poor and Black in the Rural South (New York: Laurel, 1968), 121–138, 339; Feldstein, “‘I Wanted the Whole World to See.’” The actors are coded as white because the song is sung in the first person. Gentry attended UCLA and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music but did not complete either program, at least according to current knowledge. Murtha, “Ode to Billie Joe,” 38.

- See Kathy Mattea, “Ode to Billie Joe, Classic Country Cover by Kathy Mattea,” Facebook, June 3, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/KathyMatteaMusic/videos/1728652877171688/. For Tyler Mahan Coe’s take on “Ode to Billie Joe,” see his podcast episode “CR004 Bobbie Gentry: Exit Stage Left,” November 14, 2017, in Cocaine and Rhinestones, produced by Tyler Mahan Coe, podcast, 1:44:36, https://cocaineandrhinestones.com/bobbie-gentry-exit-stage-left.