Welcome to our virtual book tour. Since so many literary events have been canceled or postponed during the pandemic, we’re bringing authors with new books directly to you. We hope you’ll get to know an author or book to add to your reading list. We also encourage you to support your local bookshop.

A Good Meal Is Hard to Find presents 60 recipes by Martha Hall Foose inspired by the paintings of Amy C. Evans. Below, novelist Shay Youngblood talks with the two about their collaborative process.

Shay Youngblood: Amy, when I met you in Oxford, Mississippi, in the early 2000s, I remember your distinctive style of painting, the iconic southern images, the vintage color palette and vintage compositions. How did your style develop?

Amy Evans: Oh, thank you for remembering those details! I landed on this “style” of painting quite by accident. When I was working for the Southern Foodways Alliance, I maintained a relationship with my gallery in Houston—Koelsch Gallery, where I’ve exhibited since 1997—and kept a commitment to participating in one show a year. Honestly, that is the only thing that kept me painting while holding down a full-time job.

Every year, as the show deadline approached, I would sit down to paint and feel like I was starting from scratch. Inspiration really hit one day in 2006 when I was looking around my studio for something to paint, just anything to get my creative juices flowing. I started painting little objects around my house—a ceramic bird, a brass bull figurine (I’m a Taurus!), an orange rabbit’s foot keychain, a tin lion toy, the American Beauty Butter box that I brought back from a trip to New Orleans. I loved creating still lifes with these objects, and I found that, as I worked, a little story would come to mind. So I decided to incorporate these stories as one-sentence titles to accompany the paintings. Each of those early paintings—Eliza, Ferdinand, St. Anthony, Frank, and Estelle, respectively—appear in the book, and I still have all of those objects of inspiration. As I kept working with this narrative approach, I stumbled upon so many “stories” that I wanted to paint.

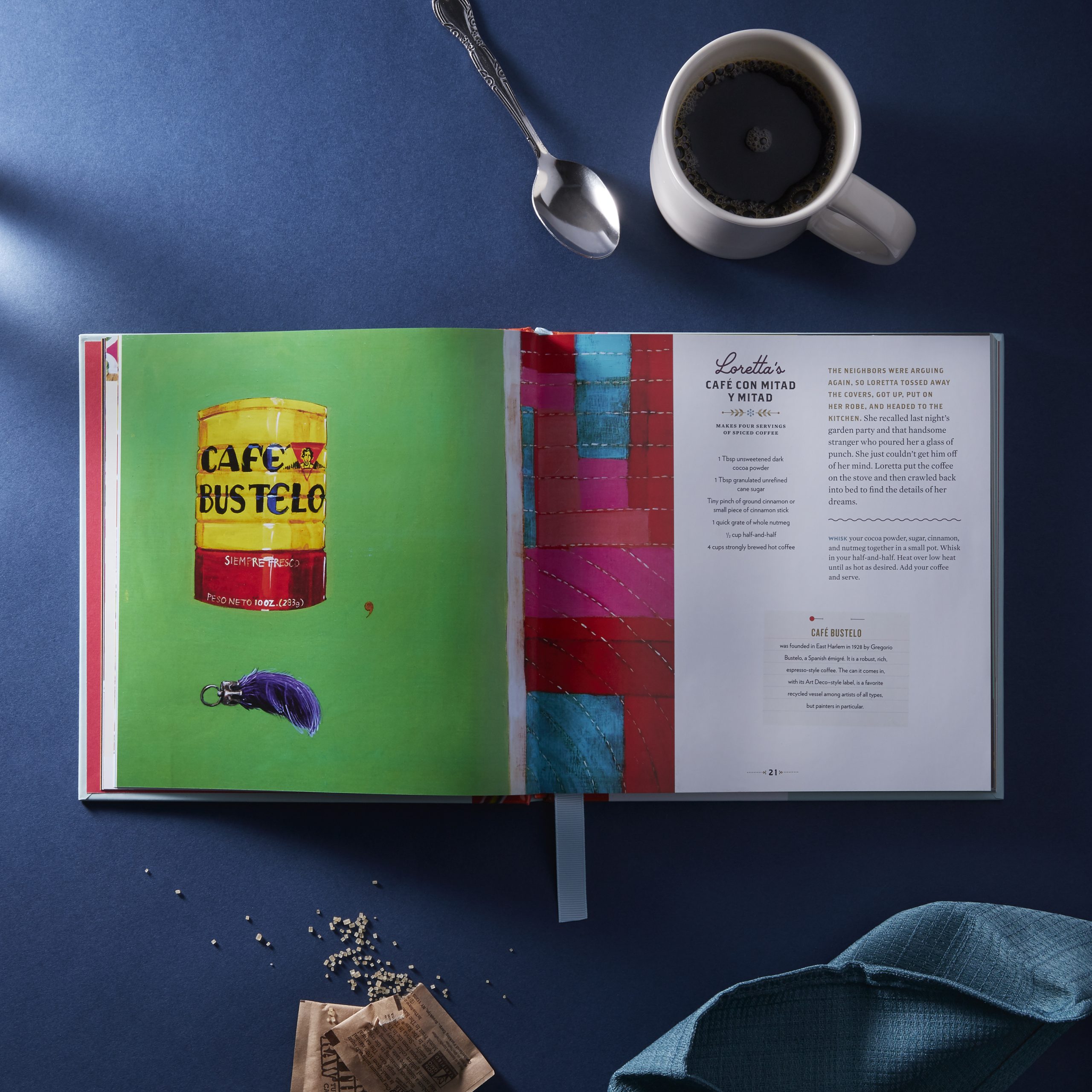

24×24”, acrylic on wood panel, 2014 (from “Marge’s Usual Sunrise,” p. 18, also featured in “Angela, Agnes, Esther, and Ivy” from the Spring 2015 Issue).

SY: In A Good Meal Is Hard to Find, the recipes enhance the stories and, in some cases, complete them. How did you marry the images and the recipes?

Martha Hall Foose: Amy and I spent a long time filling in the back stories of the subjects of her artwork. We just imagined what they liked, what they would make from scratch, and who would take some shortcuts.

AE: We had so much fun dreaming up full lives for the women in my paintings, which turned into hilarious conversations. Martha felt sure that Camille (p. 50) was good at duplicate bridge, and I knew that Josephine (p. 144) was thrifty, always hunting for a good coupon or sale. We both had very definite ideas about who these women were and even how they were similar to some of the women in our lives.

As for the recipes, Martha took direct inspiration from whatever food or drink item was illustrated in the painting and then developed a recipe around that—a saltine quail recipe for the painting of the saltine and a ceramic bird, cannellini salad based on the painting of a tin of cannellini beans, sardine crisps inspired by the tin of sardines I painted in Louise.

I really have to celebrate Martha for making my painting of canned baby corn fit into the cookbook! That’s one of my favorite recipes, too. Some paintings didn’t offer up obvious visual inspiration for a recipe though, so Martha had to make it work. Take Agnes’s Graton Firecracker Popcorn (p. 78). My painting is of a vintage package of Black Cat brand firecrackers—nothing food related—but Martha still found inspiration. So far, there have been a few readers who just think that I illustrated Martha’s recipes, but it’s really the other way around. Martha illustrated my paintings with her recipes. She really helped bring them to life.

SY: The title of the book is a nod to the Flannery O’Connor short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” set in Georgia in the early twentieth century. Amy, how did your time collecting oral histories for the Southern Foodways Alliance inform the stories and paintings?

AE: During my time with the SFA (2002–2014), I collected oral histories all over the South. All of those encounters inform how I interact with the world: talking to strangers, practicing deep listening, and finding nuggets of inspiration. The true Delta inspiration is evident in the paintings Stella (p. 105) and Lenore Anne (p. 82). What’s funny about the Lenore Anne painting though is that it’s one of the few paintings that came after the recipe. As Martha and I were working on the book, there were some holes in the list of recipes—we needed another vegetable here, another lunch thing there—and we both really wanted to include Delta tamales, hence the hot tamale ball recipe. I included nods to two of my favorite Mississippi Delta Hot Tamale Trail purveyors, Scott’s Hot Tamales in Greenville, Mississippi, and Joe’s White Front in Rosedale.

What might catch people by surprise is that there’s an awful lot of Florida in the book. I never painted an oyster or oyster shell until I spent time in Apalachicola, Florida, to document the area’s seafood industry in 2006. The place and its people are so very dear to me, so inspiration from that particular part of Florida crops up in my paintings fairly regularly now. Some examples from the book: the mullet in Ida (p. 52), Joseph (p. 88—the number 32320 in that paintings is the Apalachicola zip code & “Bay Beauty” is a refence to the Apalachicola Bay), the oyster on p. 94, and Ula May (p. 103—this paintings is from a series I did in 2016 called “Things That Go With Oysters” that I exhibited in Port St. Joe, Florida).

SY: Martha, what informs the way you create original recipes?

MF: I try to set up the home cook for success. In this case, we wanted to make sure the recipes drove the narratives of these characters’ stories forward. And, mostly, that they were delicious.

AE: What I really love about Martha’s recipes is that they’re not fussy. I’m a single mom, so I don’t have any shame in cutting corners, like buying a grocery store rotisserie chicken to make posole or using a refrigerated pie crust for the pot pie. That said, there are a few labor-intensive recipes in the book—Grace’s nabs and Flannery’s cake, for example—but those, to me, are like special-occasion recipes. Things for when you really want to show out.

SY: I love your sense of humor in the stories. Who are some of your literary inspirations?

MH: Amy is a laugh riot. Since these stories were kicked off by her painting titles, I just followed her lead. She made this collaboration a joy. We tickled our own selves a bunch writing this story-cookbook. My literary inspirations are Mary King O’Donnell, Florence King, and Clyde Edgerton.

AE: Well, that Martha is a laugh riot, too, I’ll tell you what. We really have a similar sense of humor, so the quirk came easy. My literary inspirations are, of course, Flannery O’Connor, as I mentioned, Eudora Welty, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison. There are two Flannery-inspired paintings in the book (one was inspired by one of Flannery’s letters, and the title of it is “My peachicken has one trick: he runs up to anyone holding a cigarette and snatches it away and eats it, Flannery O’Connor.” It tickles me to no end that there’s a picture of a pack of cigarettes in a cookbook!). I was really thinking about Zora when I was making my Zelda painting (with a nod to the Harlem Renaissance in a beer bottle). I can’t tell you why I didn’t just name her Zora! Silly me.

16×24”, acrylic on wood panel, 2012 (from “Vi’s Sherry Pot Pie,” p. 106, also featured in “Angela, Agnes, Esther, and Ivy” from the Spring 2015 Issue).

SY: Which recipe should I absolutely prepare? And what is your favorite?

MF: Josephine’s Chocolate Omelet Flambé (p. 144). Because you probably haven’t made one before and because flambé is fun.

I love them all but Gayle’s Chicken Posole (p. 55) is my favorite because there’s always hominy in the pantry and a rotisserie chicken is easy to get.

AE: I think you should absolutely prepare Flannery’s Gracious Coffee Fudge Cake (p. 147). It’s a commitment, but the payoff is huge. Plus, you can bake it for a special occasion or none at all, share a few slices with friends and hold some back to have for breakfast. Or, if it all goes to hell for whatever reason, you can keep it all to yourself and sit down for a strong drink because at least you know you tried.

Hands down, my favorite recipe in the book is Esther’s Diminutive Crisp Corn and Curry Comeback. Kudos go to Martha here because she didn’t shy away from creating a recipe around the painting of a can of baby corn that I wanted to include in the book. Because, come on now, who really likes baby corn? But the recipe she came up with—fried baby corn!—is just so genius and silly and perfect and, I might add, delicious. It just really is a wonderful symbol of our collaboration.

SY: After reading your book, I felt like I’d been to a Sunday-after-church potluck with folks from many cultures and traditions, and I was stuffed. How have other cultures transformed or contributed to southern cooking as we know it today?

AE: This is definitely something that rang true as I did fieldwork across the South. I worked on oral history projects documenting the Greek influence on Birmingham’s restaurant culture, the Lebanese and Chinese communities in the Mississippi Delta. And, of course, growing up in Houston, which is now I think widely considered the most diverse city in the country, I grew up eating all kinds of food, namely Mexican and Vietnamese. This conversation reminds me of my interview with Carol Mohammed Ivy in Yazoo City, Mississippi. Her father was from Syria, and Carol and her family grew up eating traditional Middle Eastern dinners ever Sunday. Today, Carol makes her family’s meat pies with canned biscuit dough. Which brings us right back around to A Good Meal Is Hard to Find. I love being a part of that circle.

MF: You know ten, twelve years ago, when I wrote my first cookbook, at the end of the recipe, if there was the least bit of anything that you couldn’t get at the Sunflower or Jitney Jungle [grocery stores], you’d have to have a specialty place to order it from. But now, any ingredient you want can be on your doorstep the next day, so it’s not a barrier to exploring new flavors.

SY: What kind of substitutions can a home cook make when their pantry might be limited in times like these, when many people are sheltering in place due to the pandemic?

MF: Pulse some long grain rice through a food processor to make up some broken pieces of rice to make rice grits. Sour some whole milk with lemon juice, vinegar or cream of tartar to make a substitution for buttermilk. Throw in any sort of bean in the place of another. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” after all, and how most recipes evolve. Most times I think recipes should be a jumping off point for cooks, in the first place.

AE: Recipes as a jumping off point, yes. I feel like some home cooks are afraid of substitutions, but times like these really force you to be creative or do without. The other day my daughter and I wanted to make Matilda’s Long-Lasting Grande Fours, but we didn’t have all of the listed ingredients. We just used what we had and went completely without something else, and it was fine. In fact, we didn’t even trim the sides of the cake as Martha’s recipe directed. But we made a cake, put flowers on it, and it looked gorgeous, and we really felt like Matilda would’ve approved—Martha, too, for that matter! And that’s really the spirit of this book.

Interviewer’s note: I made Stella’s Harissa Gold Chicken. Even though I added dried cherries and had to leave out the pearl onions, the dish turned out delicious and Instagram-worthy.

A Good Meal Is Hard to Find: Storied Recipes from the Deep South is available now from Chronicle Books.

Amy C. Evans is the co-author of A Good Meal Is Hard to Find: Storied Recipes from the Deep South (Chronicle Books, 2020). She is an award-winning artist, writer, and documentarian based in Houston, Texas. Her paintings have appeared in Southern Living, Southern Cultures, and on CNN’s Eatocracy and the Oxford American blog. Her writing has appeared in Saveur, The Bitter Southerner, The Local Palate, and Cornbread Nation 5: The Best of Southern Food Writing. Amy built the documentary program at the Southern Foodways Alliance, headquartered at the University of Mississippi, where she served as their lead oral historian for more than a decade.

Martha Hall Foose is the co-author of A Good Meal Is Hard to Find: Storied Recipes from the Deep South (Chronicle Books, 2020). Martha’s cookbook career began with Screen Doors & Sweet Tea: Recipes and Tales of a Southern Cook, which won the James Beard Award for American Cooking and The Southern Independent Booksellers Award. Her follow-up, A Southerly Course: Recipes & Stories from Close to Home, found its way on to Best of the Best lists from NPR and Food & Wine. She co-authored Oh Gussie! Cooking and Visiting in Kimberly’s Southern Kitchen with Kimberly Schlapman of Little Big Town. Martha also co-authored My Two Souths: Blending the Flavors of India into a Southern Kitchen with chef Asha Gomez.

Georgia born writer Shay Youngblood is author of the novels Black Girl in Paris and Soul Kiss (Riverhead Books) and a collection of short fiction, The Big Mama Stories (Firebrand Books). Her published plays Amazing Grace, Shakin’ the Mess Outta Misery and Talking Bones, (Dramatic Publishing Company), have been widely produced. Her other plays include Square Blues, Black Power Barbie and Communism Killed My Dog. She is the recipient of numerous grants and awards including a Pushcart Prize for fiction, a Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award, an Edward Albee honoree, several NAACP Theater Awards, an Astraea Writers’ Award for fiction and a 2004 New York Foundation for the Arts Sustained Achievement Award.