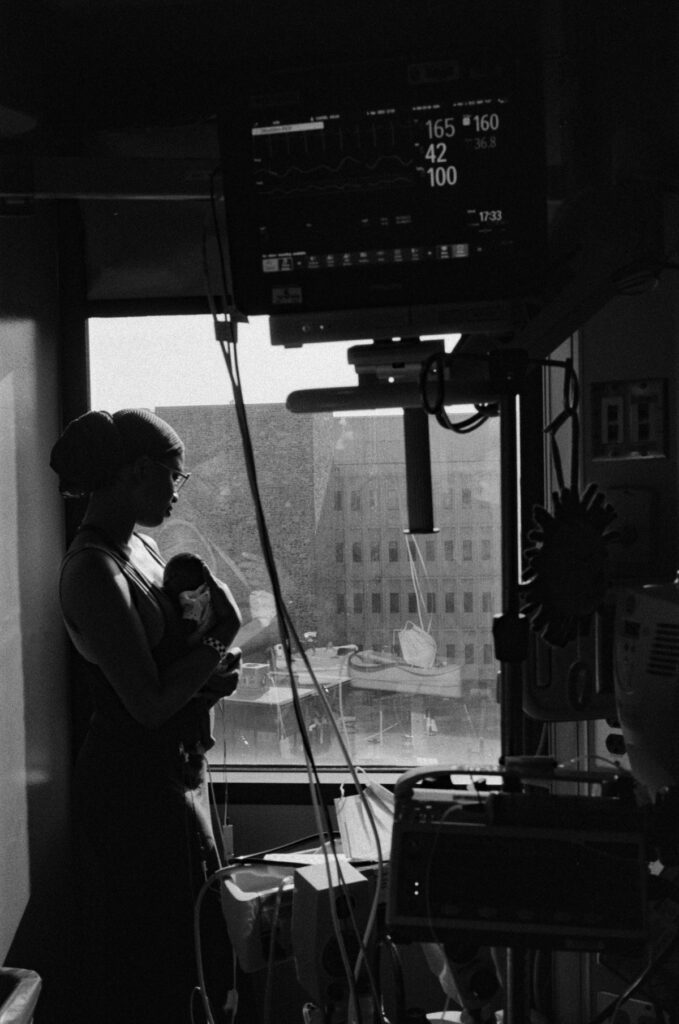

As quickly as I found myself in the family way, I just as quickly found myself giving birth. A strange birth following a car pile-up. Blood in the crotch of my underwear. Seven layers of skin peeled back and sewn together again in under thirty minutes. Suddenly, a two-pound baby was born, looking anything but healthy but still very much alive. His name is Atlas, and he’s now two. He loves the puppet Elmo, he looks just like his father, he has my eyes and reddish-brown hair.

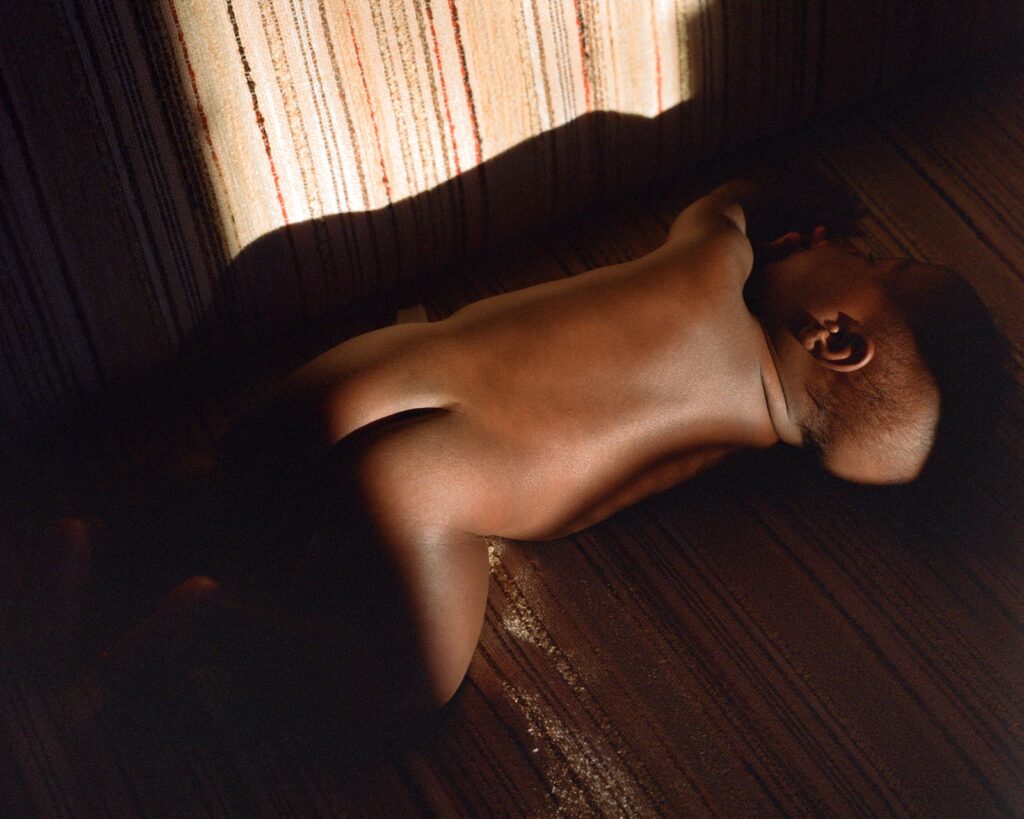

When I wasn’t at my son’s bedside in the neonatal intensive care unit, I immersed myself in my work, using my practice to digest the trauma of his birth. I made portraits of my body as it stitched itself slowly back together. I photographed the matriarchs of my family (mother, grandmother, and aunties) and the new mothers in my community. I also photographed folks who have not given birth but are still actively mothering in their own unique ways. The work I created during that time explores Black maternal lineage and family lore passed from generation to generation.

After Atlas’s three-month hospital stay, he and I did one night alone together in my apartment. Given that my son’s father was based in Virginia for school, the bulk of the parental work sat on my shoulders. “Help” was a word that sat perched at the seat of my mouth almost daily—oftentimes uncomfortably. I moved out and began living part-time with my parents and my son’s grandmother, though my lease wasn’t up for another month.

Every day felt the same: Wake up (if I got any rest at all), feed the baby, change the baby, baby naps, bath time, another bottle, nap, pump. Rinse. Repeat. Rinse. Days with no clear start and no clear finish. It’s accurate to say that by month three of my maternity leave I was going crazy with a fervent desperation for escape. Escape from the weight of caregiving, from being taken for granted, an escape from slowness, an escape from needing so much “help.” I prided myself on my photographic practice, one truly birthed from the red soil of the American South. Before Atlas was born, I developed a project on Black cowboys and another on Black southern youth exploring their sexuality. I had completed one of the most notable assignments of my career, photographing Beyoncé for the cover of British Vogue, which catapulted everything forward. I had also just been on the other side—a starving artist—and was afraid of everything coming to a halt again. I’m not entirely sure what I thought being a parent would entail. In a perfect world, I thought it would be something I could do alongside my son’s father, maybe even in a place of our own. But work was slow, and money was almost nonexistent.

Amid all this turmoil, one night was especially bad. My son would not sleep. He was a little over five months old when I developed a breastfeeding aversion. Night feedings felt like nursing a puppy, the pulling and prodding at raw skin. I remember his small mouth latching onto my breast. I was sleepy to the point of delusion. I looked down at him, and his round face, made puffy by prescribed diuretics, morphed into that of an old man. I truly hollered, which, in turn, made him scream back at me. My mother came into my room to check on us. I told her in hysterics, “I don’t know if I can do this.” She picked him up and hightailed it out of there. In not caring for myself properly, prenatal vitamins had taken a back seat. I had depleted myself of proper nutrition, and my breastfeeding aversion was essentially a bodily preservation tactic. Grief had become a squatter in my body. Grieving what my life used to be, how living used to feel, what home used to be. Grieving how the relationship with my son’s father had become unrecognizable, as the distance between us grew more cavernous by the day. When I thought about the life I wanted Atlas to have—that I wanted myself to have—this was not what I envisioned. I’d come to believe that I was a disappointment to everyone in proximity to me.

The following morning, I drove to Target. The trip should have been to “the lady” (aka, atherapist), but I was grateful to have time to myself. I told no one how sad I had become, and I especially told no one how I saw my son’s face change the night before. Instead, I purchased a Kindle. In some ways, I believe reading saved me. The books I read served as a distraction for how often I thought or daydreamed about death. Perhaps I did not even long for the permanence of dying, just a deep sleep—a sleep so long that when I finally found myself awake, I’d be in another stage of my life, one where I had my shit together.

I reflect on the first two years of my son’s life, and I don’t think I would have been able to make strides as a mother (or any kind of human) without the support of my friends and family, or my return home. While my postpartum hormones have leveled out, sadness still rears its head more often than I’d like. But I’ve made plans to do something about it, revisiting talk therapy and taking the time to shift my perspective to one of gratitude. Countering every negative thought with a positive one: “You live with your parents.” My son and I have a roof over our heads, and my parents love having us here. “Work is slow, what is wrong with me?” I am doing the work I love, and I am living in my purpose. “Being a mother is hard.” My son is quickly growing, he desperately wants to be seen and to communicate with me. He is beautiful and necessary. My job as a mother is beautiful and necessary. “Life is hard.” Life is also devastatingly gorgeous.

A Durham, North Carolina native by way of Dallas, Texas, Kennedi Carter is a visual artist with a primary focus on Black subjects. Her work highlights the aesthetic and sociopolitical aspects of Black life, as well as the overlooked beauties of the Black experience: skin, texture, trauma, peace, love, and community. Her work aims to reinvent notions of creativity and confidence in the realm of Blackness.