This will probably be the last time that I hold forth at length about corned hams. This treasure of eastern North Carolina culture has been a cause of mine since I discovered that no one had ever heard of it outside of the three or four counties around where I grew up—New Bern in Craven County. Now, the world has taken notice and my work is done. Proof of this is found in the meat counters of the Piggly Wigglys, where ham is returning after an absence of many years. I give its appearance on an episode of PBS’s A Chef ‘s Life the credit for this. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Corned hams were always around when I was a child. The first one of the year would show up beside the turkey at Thanksgiving. There would be another one at Christmas, then probably a third on New Year’s Day. Corned hams were our winter ham. By the time of my grandmother’s Easter Brunch, they were replaced by a “pink” or ham sandwich ham. I never questioned this. It was just what people in the community did.

When I moved away from the coast as a young man, corned hams, along with kibbeh, labneh, and Syrian bread all vanished. The Middle Eastern food was gone because I was no longer among the Lebanese who had settled all over eastern North Carolina in the 1920s and ’30s. No such explanation for corned ham. I found this inexplicable because they are so good. My father would occasionally pack one in a cardboard box and send it up to me on the bus. They are salty enough to survive the trip without refrigeration—at least, that’s what I decided to believe, and it must be true because there were never any casualties. So from time to time in the fall and winter, I would host dinner parties to celebrate their arrival. Hams are big, even if you try to get a small one, so you need a large guest list. The rest of the meal would be simple—mashed potatoes, cornbread perhaps, probably salad. And the same nut torte that I always make for dessert. The parties always finished in the same way. Everyone would end up in the kitchen around the ham platter, picking at it with their fingers while they continued to drink and talk. Often, my good nights would include the question, “How did you all end up eating a whole ham?”

My father would occasionally pack one in a cardboard box and send it up to me on the bus. They are salty enough to survive the trip without refrigeration—at least, that’s what I decided to believe, and it must be true because there were never any casualties.

Once when I was home in New Bern for a visit, my father announced that Gwen was going to show me how to make my own hams so that he wouldn’t have to put them on the bus anymore. Gwen, who ran the meat department at the local Pak-A-Sak, had become a friend of the family. A lesson with her was a great bit of luck, because it was around that time when corned hams began to change and then disappear from meat counters down east. People like Gwen would still make them, but you had to know who to ask to reserve such hams.

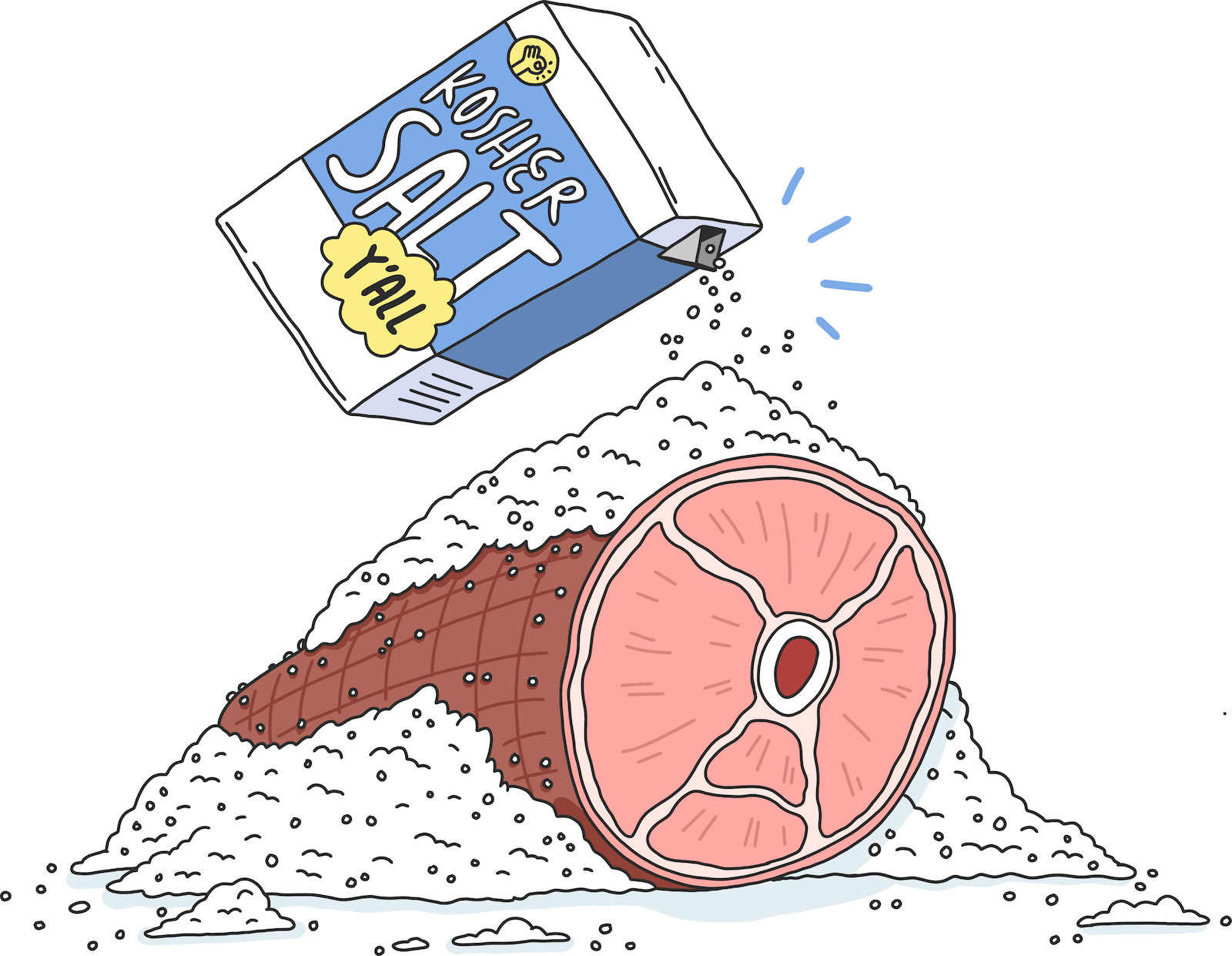

The villain in this story, I’ve always thought, was a new method of production that replaced the traditional one. Instead of packing the fresh ham in salt as people had always done, someone had begun injecting them with a saline solution. This made for harsh and stringy hams that refused to become tender no matter how long they were cooked. Corned hams soon fell from favor and vanished. People mourned and reminisced. “They are always too tough now.” “You have to order them special!” “You can never find these anymore.” But Gwen and I and a few others had the secret, and it was amazingly easy. A certain amount of organizing is necessary, but the recipe is simple. There are two ingredients: a fresh ham and salt. Plus time. After years of observation, I have decided that eleven days is an optimal amount for the cure.

People mourned and reminisced. ‘They are always too tough now.’ ‘You have to order them special!’ ‘You can never find these anymore.’

I’ve encountered two theories as to the origin of corned ham but neither is verifiable. One simply suggests that these are the first hams cooked after the pig kill. Simple duration was the impetus, and then people developed a taste for it. The second theory posits that this type of cure was developed for use on ships where the presence of a fire for smoking would be unwelcome. Both make sense.

In 2015, I was invited by my friend Vivian Howard—a native of Kinston, not far from New Bern, via Highway 70—to join her on her television show. She wanted to make a corned ham for her holiday spread. “There’s a catch,” she explained over the phone. “We want to start from scratch.” This, of course, meant beginning by killing the pig. You can watch our antics on TV. I’ll only say that if that were the only way I could make a corned ham, I might let them vanish, too.

A HAM HOW-TO

I like a ham that weighs around twenty pounds, but later in the year the smaller ones are hard to find, so I make do with whatever is fresh. Hams that have been frozen are okay but they are never quite as tender. First, you wash the fresh ham and pat it dry. There are usually three places on the ham where a bone protrudes—one at each end and then another on one side, which is blade-like. Take a sharp boning knife and insert it along each of these bones as deeply as you can. At the small end of the ham this will be almost impossible, but at the other two you should be able to go in about four inches. Work to enlarge the incisions a bit and cram as much salt as possible into all three places. Again, the narrow end of the ham won’t take much, but the other two can. Then, coat the outside of the ham with salt. I use an entire two-pound box of Kosher salt for this, but when I asked Gwen what she used, she shrugged and said Morton’s. Refrigerate the ham, loosely covered with plastic, for eleven days. Since hams are so large, this often requires some reorganizing. It’s best if the ham is in stainless steel or glass rather than aluminum. On the eleventh day, thoroughly wash the ham, flush out all of the salt from the pockets you made, then soak the ham in fresh, cool water overnight.

The next day, place the ham skin-side-up in a roasting pan, on a rack. Put a little water in the pan. Cover the ham either with a lid or with foil and bake at 350 degrees for twenty-five minutes a pound. This can take all day. For the last three hours, uncover the ham. For the last hour, dislodge the carapace of skin if you can. Leave it in the pan but move it away from the meat. It will turn into the most astounding cracklins. A boning knife should pass easily through the thickest part of the ham when it is done, and the knife blade should be almost hot enough to burn right when it comes out of the meat. Personally, I like to cook a ham until it is falling off the bone. Let it rest about forty-five minutes before slicing. Serve at whatever temperature the ham is at dinnertime. The drippings are greasy, but delicious. Just spoon them over the meat and potatoes, don’t make gravy. The ham is delicious the next day, but it will become a different food. It’s never the same when reheated.

I ate so many that I felt saturated with grease. It was heavenly.

I think, because of the shortness of the cure, neither the bone nor the scraps are particularly good for seasoning collards or soup. The cracklins, on the other hand, are ethereal. Usually, people eat half of them right away and finally have to flee the kitchen to save themselves. Last week the cooks at Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill rough-chopped day-old ones and threw them into the fryer, producing veritable clouds of pork rinds reminiscent of the best chicharrónes found in Mexico. I ate so many that I felt saturated with grease. It was heavenly.

This essay first appeared in the Coastal Food issue (vol. 24, no. 1: Spring 2018).

Bill Smith is the chef at Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the author of Seasoned in the South and Crabs & Oysters. He can frequently be found in the pages of publications including Garden & Gun, Gravy, The New York Times, and Southern Living, as well as riding his bike through the streets of Chapel Hill.

Beardy Glasses is an illustrator and art director based in Atlanta, Georgia.