Katharine Hayhoe is the Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy. She is also Paul Whitfield Horn Distinguished Professor and Endowed Chair in Public Policy and Public Law in the Public Administration program of the Department of Political Science at Texas Tech University.

Hayhoe has published over 125 peer-reviewed abstracts and publications and coauthored Downscaling Techniques for High-Resolution Climate Projections: From Global Change to Local Impacts (Cambridge University Press, 2021), and served as lead author on key reports for the US Global Change Research Program and the National Academy of Sciences, including the Second, Third, and Fourth US National Climate Assessments. Her TED talk, The Most Important Thing You Can Do About Climate Change: Talk About It, has received over 4 million views. Her new book, Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World, was released in September 2021.

BRYAN GIEMZA: I think it’s fair to say that even though you’re the only climate scientist within a two-hundred-mile radius here, you speak Texan insofar as you understand how to connect with people in this part of the world, and you understand something about their views and their hopes. Your husband is from Virginia. So I’m curious: At this stage, do you feel like the South has in any way shaped your identity? Have you “southernized,” dare I ask, in some way?

KATHARINE HAYHOE: When I first moved to Lubbock, I remember going to the grocery store, looking for something fairly normal. I couldn’t find it, so I asked a grocery store employee to help me. She said, “I’m sorry, I don’t know what you’re asking for.” I repeated myself several times, but she still couldn’t understand me. Finally she asked where I was from. When I replied “Canada,” understanding dawned across her face. “Oh!” she cried. “That’s why I don’t understand you. You’re speaking French!”

BG: Oh, wow.

KH: Since then, I have learned to suppress my Canadian accent somewhat. I’ve also learned to appreciate what southerners call tea versus what I would call tea. I love Texas barbecue and the wide-open skies that we have here. And I’ve also learned why people are so challenged by the issue of climate change and why they are so worried about climate solutions. But I also appreciate the fact that many of the stereotypes we might hold of Texas and of southern states are not true at the individual level, and sometimes not even true at the state level. When we spend the time getting to know people, we realize that almost everyone has more facets than we might see at first glance.

BG: That’s a great point.

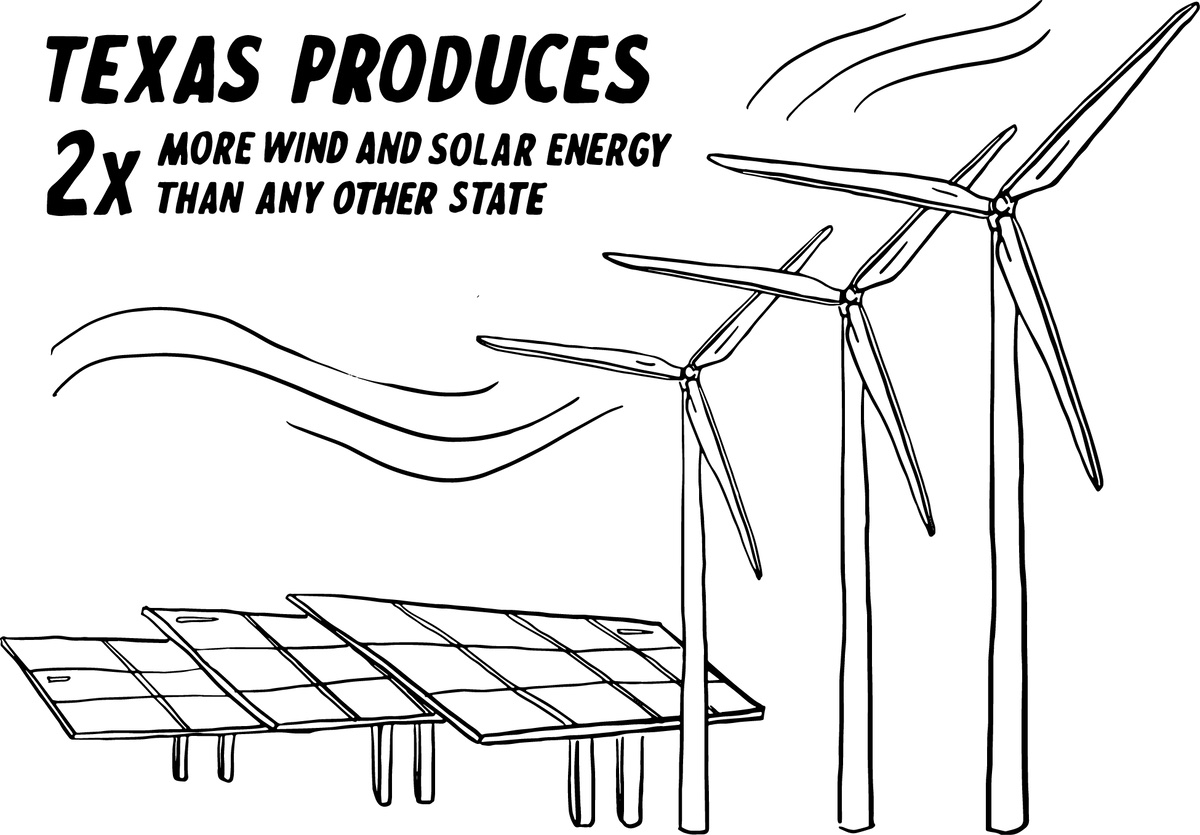

KH: It often surprises people when I tell them that Texas produces double the wind and solar energy of any other state. Our big cities, from Houston and Dallas to Austin and San Antonio, all have aggressive climate action plans. There are people all over Texas working on conservation, green infrastructure, regenerative agriculture, clean energy, and climate justice. So much is happening in Texas itself, and I see many of these same changes happening throughout other southern states.

BG: Houston is such a remarkable example. It’s so strong on climate action and public policy, given that it’s the epicenter of the energy sector in the past and it will be in the future—if it remains habitable. As you know, the Southeast faces a compounding set of climate concerns that do call into question its ability to support its population: hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, sea level rise, heat and humidity, loss of biodiversity, water scarcity leading to a host of issues, property loss, habitat destruction, weakened infrastructure, agricultural impacts, and some pretty appalling health outcomes as one of the most affected regions of the country. At the same time, the South is obviously poised to lead on the issue of climate change. You’ve often said this about Texas too. How might regional identity serve this goal? And what is the South’s untapped potential, in your mind, for fighting climate change?

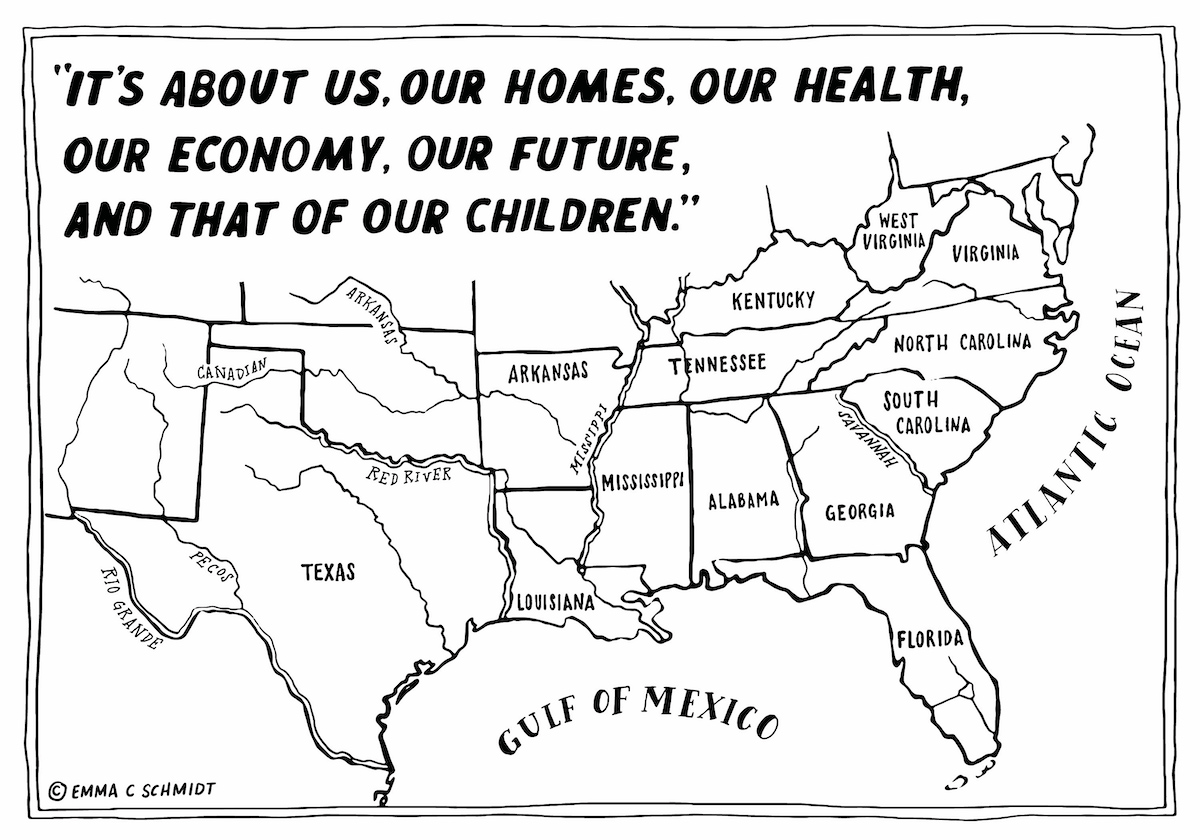

KH: The number of billion-dollar weather and climate disasters has increased from about one every four months back in the 1980s to one every three weeks today. Of course, we’ve always had hurricanes and floods and droughts and storms. But as the planet gets warmer and warmer, we see that hurricanes are intensifying faster and they’re dumping a lot more rain on us. We see that heavy rainfall itself is getting more frequent. When our droughts occur naturally, as they always do, they tend to be more intense and they’re lasting longer. Heat waves are much more frequent and much more dangerous. These changes, what I call “global weirding,” are affecting all of us all around the world. But because of our geographic location, some states are more vulnerable than others. And you are right: the US South is the most vulnerable place in the continent with respect to climate impacts. Texas, Louisiana, Florida—the states that are in the direct range of hurricanes—are the ones who are bearing the brunt of these impacts. And that’s the bottom line. It isn’t about Antarctica or the polar bears. It’s about us, our homes, our health, our economy, our future, and that of our children.

BG: We’re so often sorted into reductive political categories—red/blue, secular/religious, southern/northern, on and on. How do we think beyond these categories to unite in the fight against climate change, especially since this polarization is in the vested interest of certain political actors and those who seek to sow chaos and division for political ends? How do we get past these categories? What paths do we have to bridging and overcoming these differing identities and beliefs so that folks can come together and make change?

KH: According to Pew Research, the United States is currently more politically polarized than at any time since the Civil War. Increasingly, over the last few decades, people have come to identify with a political party. It is not just who you vote for, it is literally who you are. When we take that step, which I personally feel is a very unhealthy one—to adopt politics as an identity rather than just a tool or a means or a measure to express our opinions on important issues—that’s when this polarization becomes so toxic.

The Beyond Conflict Institute has traveled around the world for many decades studying countries that have conflict occurring in them. They were in South Africa during apartheid, in Ireland during the days of the IRA. Today, though, they are focusing on the United States. And what they’ve found is that people have become so polarized they view someone who votes for the other party—and this is happening on both sides—as not even human, as an enemy rather than a fellow citizen. It has become a zero-sum game, and when that happens, we all lose.

So what’s a healthier way of looking at things? First, the Yale Program on Climate Communication proposes that rather than viewing people in two categories, them or us, instead, we should consider six different categories. At one end, you have people who are alarmed and people who are concerned, and that makes up over 50 percent of the population. Just under 20 percent are cautious. They’re worried, but they’re reserving judgment because there’s a lot of conflicting information out there. Then there’s a really tiny group of folks who are disengaged. After that, we have about 10 percent who are doubtful and about 10 percent who are dismissive.

Doubtful people have really vested their identity in their politics. And it makes sense that they’d be doubtful about climate change, because the further right you go toward the right-hand side of the political spectrum in the United States—and, sadly, this is increasingly the case in Canada, the UK, Australia, Brazil, and the EU as well—the more likely you are to be hearing from people who are telling you that climate change isn’t real, it’s not serious, we don’t have to fix it, it’s just a government ploy to take your money and impose communist control and rob you of your personal liberties. Doubtful people don’t hear anything other than it’s not real, it’s not us, it’s not serious from people they trust. But they haven’t vested their identity in denying the science. Their identity is based on the politics and their objections are 99.9 percent solution aversion. They’ve been told that there aren’t solutions that are consistent or compatible with their values, and that’s why they reject the reality and severity of the issue.

If you say, “It’s a big problem, but I don’t want to fix it,” that makes you a bad person, and none of us really wants to be a bad person. So instead we make up all these excuses like, it’s natural, or it’s just the sun or volcanoes, or the climate scientists are just making it up, or electric cars are worse than internal combustion engines for the environment—don’t those stupid liberals know that? to hide the fact that we don’t want to act.

When we speak with people who are doubtful, if we share real solutions that have real benefits today and help with climate tomorrow, we might not even have to mention the climate change part. We can often find surprising points of agreement because they might want to be a good steward of their land, or save money, or support local businesses or local industry, or there might be a value they already have that dovetails with a climate solution. If we can show them that who they already are is the perfect person to support climate action, that means they’re acceptable; they don’t need to change. They are already okay. It removes so much of the defensiveness around the discussion.

But then you have the last group—dismissives—and [those in] this last group punch above their weight. I hear from dismissives on social media dozens of times a week. If you look at the comment section under any news article online, dismissives are everywhere. And because they’re everywhere, we’re often deceived into thinking that there’s a lot of them. But there actually aren’t. Only about 10 percent of people in the United States are dismissive.

What’s the difference between someone who is doubtful versus someone who is dismissive? A dismissive person is somebody who has actually invested their identity in rejecting the science. Often, it’s not only the science on climate change. It frequently includes the science on vaccines, COVID, and all kinds of things that they think might pose a threat to their identity.

Because of this, they perceive any discussion of the science as a direct threat to their identity. That’s why we can’t have a constructive conversation about an issue that they have made into an identity marker for themselves: because that discussion will be interpreted by them as a personal attack. Say a dismissive says climate change is caused by volcanoes. I reply that no, as a matter of fact, all the volcanoes in the world produce as much heat-trapping gases as three medium-sized US states every year. To you and me, that might sound like I’m just countering a false statement with a neutral scientific fact. But to a dismissive, their brain interprets that response as you’re wrong, you’re stupid, you’re ignorant, you’re evil. In fact, I define a dismissive as someone who, if an angel from God with brand-new tablets of stone saying “Global warming is real!” in foot-high letters of flame appeared before them, that still wouldn’t change their mind. So why would I imagine anything I say would?

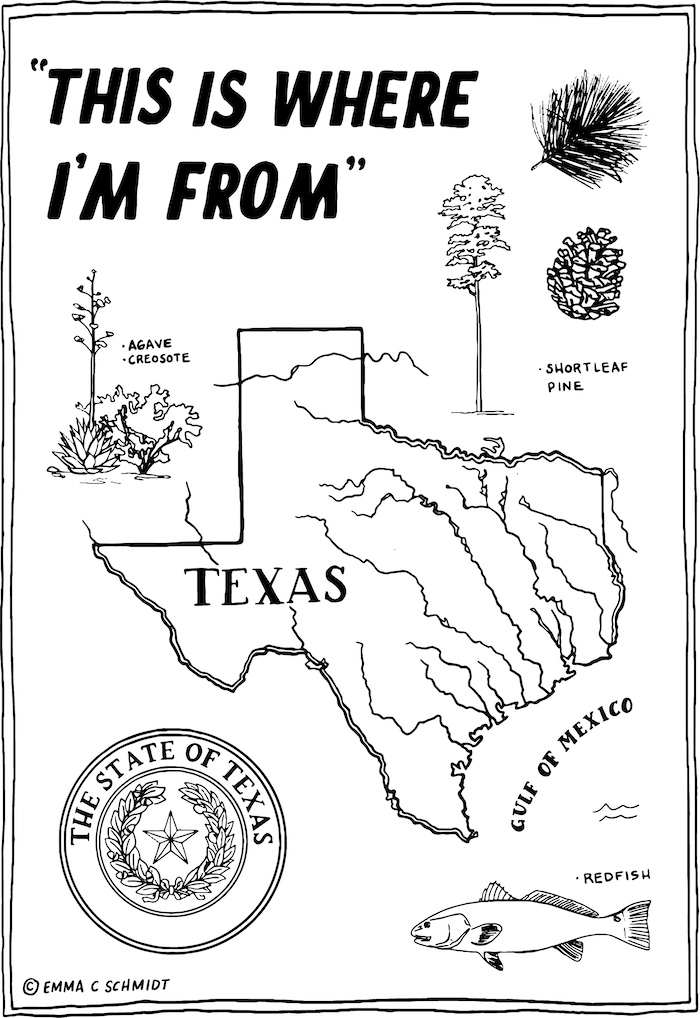

The bad news is that I don’t think we can have positive conversations about hot-button issues with dismissives. The good news, though, is that most people are not. On climate change, for example, the vast majority of people are already worried, but they just feel stuck, they don’t know what to do. Here again, talking about local solutions is so powerful, because many local solutions have immediate benefits, whether it’s for our health, our pocketbook, our local economy, our own homes, neighborhoods, schools, or places of work. When we talk about positive solutions, that’s where we can really come together. Often, these solutions invoke people’s common sense and their pre-existing values such as pride of place, a sense of this is where I’m from, this is where my family lives, and so of course I want it to be a safe, healthy place for me and my children to continue to live in the future. When we start to connect our head to our hearts—and a sense of place is very powerful at doing that—that’s when we can see real change happening and people buying into making changes because of who they are, not because of who someone else is trying to make them be.

BG: That’s something that would resonate powerfully with southerners. As you know, around 8 percent of the angriest people at each edge of the political fringe are the most amplified voices, algorithmically speaking, online. So, to your point about dismissives and the unpersuadable, they’re disproportionately salient, unfortunately. And I think that’s part of what’s led to the perception of the other as the enemy.

You are a scientist, a science communicator, and a person of faith. How can we use religious values, such as stewardship and compassion, to guide our actions on climate change or to persuade our communities to act? Obviously, this could have a particular impact in the South of the Bible Belt, which is reportedly the most devout region in the country and around 77 percent Christian.

KH: When it comes to effective conversations on hot-button topics like climate change, my number one tip is this: don’t begin with something you disagree with people on, but begin with something you agree with them on.

The closer that topic is to their heart, the more meaningful the conversations are. As examples, I’ve had conversations with people over a shared love of knitting or beach vacations. I know others who have had conversations with people over the fact they both play ice hockey or they both do online gaming. There are so many different topics we can have conversations on, but the deeper those go into our identity, the more impactful those connections are.

For many of us who are people of faith, our beliefs go quite deeply into our identities. In fact, our identities, to a large extent, are vested in those beliefs. That means that a shared faith can be a very effective place to begin a conversation about climate change.

I want to caution, though, that that’s not always the case. In the United States, these days, many people self-identify as Christians culturally and politically rather than theologically. In fact, surveys have shown that 40 percent of people who call themselves evangelical Christians don’t go to church. That implies that just because somebody calls themselves a Christian doesn’t mean that it is something they vested their identity in. Today in America, the word Christian—including Catholic and evangelical, and other terms related to being a Christian—those words are actually political … what’s the word I’m looking for?

BG: Signifiers, maybe?

KH: Yes, those words are increasingly becoming not theological but rather political or ideological signifiers. So imagine that I was talking to somebody who said they were a Christian and I shared with them that I was too. And then I started to talk about how I, as someone who takes the Bible seriously, have based my perspectives on climate change on what it says in the Bible about human responsibility for all living things on this planet and about care for those less fortunate than us. But imagine if they were one of the 40 percent who never go to church and their identity is not vested at all in theology. My argument wouldn’t go anywhere. It would be as if I were an ardent birder trying to convince somebody who doesn’t care about birds at all that they have to care about climate change because it affects birds. Which of course it does! But if we have to convince someone to care about birds before they care about climate change, we’ll never get anywhere.

My point is that finding those commonalities is essential, but we have to make sure when it comes to faith that it truly is a commonality. When it is, though, we can see remarkable change.

I’ve been invited to speak at many Christian colleges, and my favorite type of invitation is one that starts off with, “Well, we had a committee meeting and somebody recommended that we invite you to give a chapel service. But I was thinking, you probably don’t do that type of thing, do you?” And I can tell from their voice they’re just hoping I’ll say no.

Those are the invitations that I say yes to, right away! But before I go, I ask questions and listen very carefully to what is most important to them. It might not even be the same from one place to the next. I remember the very first chapel service that I spoke at. I could tell, from what they were saying, that some people doubted whether I really was a Christian. I decided to begin with a statement of faith about what I believe, so that everybody would see that theologically we were on the same page, before I turned to what the Bible says about caring for each other and caring for the planet and how I interpret that and apply that through science.

Some years later, I was invited to speak at a much more conservative Christian college. For them, the biggest issue they had was really focused around being pro-life. They were fully expecting me to come in and say that the only solution to climate change is abortion. That was the latest meme circulating in right-wing websites at that time, and they had picked up on it, and they were afraid that they were inviting somebody to their campus who was going to be speaking against their most deeply held values.

For them, I constructed a whole presentation around the concept that if we are truly pro-life, which I would define as from conception to death, then we would be out at the front of the line demanding climate action, because climate change and pollution from fossil fuels affect the unborn, babies and children, maternal health, and all people throughout their lifespan, and then they disproportionately affect elderly and senior citizens as well. When I framed it like that, I had people telling me, I never put those pieces together before, but it totally makes sense. We were able to connect at a very fundamental level because we both respected the same perspectives. We live our life by the same values. We vested our identity, again, in these truths.

When someone who clearly shares the same beliefs or values as you do shows you how these can be applied to a different issue, that’s where we see tremendous change, because we’re not asking people to change who they are. When you begin with what you have in common with somebody, and you respect and elevate whatever it is that’s important to them, whether it’s their faith or the fact that they’re a good parent or a shrewd businessperson or very concerned about national security or the economy, or a good steward of their land, you are elevating who they are. In contrast to what a dismissive implicitly hears, that they are a bad person, in this case the subtext they are hearing is that you believe they are a good person. And when we hear somebody telling us we’re a good person, we’re much more willing to listen to them.

BG: Absolutely.

KH: I don’t think I’ve quite articulated it like that before, but I think that really is what it comes down to.

BG: Exactly. My conviction is that one of the more interesting moral features of the universe that we inhabit is some inscription of the good that we’re attuned to, which also meshes with the idea that we want to be good and we’re called to goodness, right? But let’s talk about language and get back to your example of rhetoric and the meme that circulated on a campus before you arrived and that threatened to color people’s perception of what you have to say.

Social justice issues such as poverty and access to clean water intersect with climate change impacts. How do we combat the negative connotations that these terms call up for some people? How can we translate the long history of activism and its benefits to all of us to climate action? Or, put a little differently, how do we encourage people to see these local issues as part of a much larger arc of justice? That’s a big question, isn’t it?

KH: It is a big question, but it strikes directly at the heart of why I’m a climate scientist. I never perceived myself as an environmentalist. My perspective was always that environmentalists care about and work to fix problems like deforestation, air pollution, and water pollution. The rest of us can support them and watch their documentaries and wish them well.

Personally, I was always more conscious of the impact of poverty on people’s lives, of how much more vulnerable people are when they don’t have a safe place to live or lack access to regular food or clean water or basic health care or education. When I learned that climate change is not only an environmental issue that predominantly middle-class white people work on and care about, but in fact, climate change is a threat multiplier, as the US military calls it, that disproportionately affects the poorest and most marginalized people everywhere, that’s when my perspective changed radically. Through a class I took at university, I learned that climate change takes every issue we’re currently confronting and makes it worse, beginning with inequity, poverty, hunger, disease, lack of access to clean water and education, and even the availability of safe places to live. That’s what made me decide to become a climate scientist, because I knew I had to do something about it. The 50 percent poorest people in the world are responsible for 7 percent of our heat-trapping gas emissions that are driving climate change, yet they are bearing the brunt of the impacts. If you look at the countries that are most affected by the supersized hurricanes, the devastating heat waves, the intense droughts, and more,those are countries like Malawi, Somalia, and Eritrea, not countries like the United States.

But even where we live in the United States, when floods or heat waves hit where you and I live, which neighborhoods are flooded worst? The ones in the flood zone where people who couldn’t afford to live somewhere better live. Which places are hotter during heat waves? The low-income neighborhoods that don’t have the tree cover and the green spaces, so they are up to 15 degrees Fahrenheit hotter during a heat wave than a wealthy neighborhood in the same city.

Climate change is, at its core, profoundly an issue of justice. The richest 1 percent in the world are responsible for a huge, disproportionate impact of this problem, and there are no lasting climate solutions that don’t address the injustices of climate impacts at the same time.

This is where the disconnect occurs, though, because climate change as an issue was first taken up by environmental groups, and decades ago, environmental groups were traditionally white, middle class, and often male. Justice issues, on the other hand, have been taken up by community and by faith-based groups that care about equity, poverty, racial justice, and more. As a result, the people working on these issues are approaching from separate populations that can sometimes even be hostile to each other, in the case of some environmental and faith-based groups.

So what do we need to do? We need to bring those two approaches together. That’s a lot of the bridging that I try to do, and I know many other people are working on this and many great organizations are doing things in this area as well. There are lots of initiatives to bring issues of climate vulnerability into the discussion through listening to leaders in Latino, Black, Indigenous, and low-income communities. They are the ones who can speak to their concerns rather than more people not from that community coming in and telling them what they need to do with their lives and their neighborhoods and their homes and their places. More colonialization is the last thing we need at this point.

A word that really describes this issue well is intersectional. It simply means that if you’re really going to address the climate crisis, you have to recognize how climate change is intersecting with other issues such as poverty, racism, socioeconomic inequality, injustice, and more. And that’s really where systems thinking comes in, because we’re all part of a system, we’re all connected to each other, and we’re connected to this world that we live in. You can’t just try to fix one thing without looking at the impact that that fix will have on another part of the system. We have to look for systemic solutions that have win, win, win, win, wins for people’s health, for cleaner air, for cleaner water, for access to more stable food sources and safer homes … and that fix climate change too.

BG: That is such a drop-the-mic answer: in addition to being a threat multiplier, climate change can be a unification multiplier and solution unifier. But we have to be thoughtful about intersectionality, if we use the fancy word—which itself has become something of a culture wars word, unfortunately a signifier and a somewhat hollow one if it’s not serving us well.

KH: You know, in the interest of effective communication, I prefer to just say climate change is an everything issue, because that doesn’t immediately set up a barrier. And then when people say, well, what is everything? then we can start asking what they care about. I’m a gardener. Okay, well, let me tell you how climate change is a gardening issue. I play football. Let me tell you how climate change is affecting football. Everything is a much more open word.

BG: Your early childhood experiences growing up in what’s sometimes called the Global South also informs a certain kind of southern perspective from the beginning for you—no matter how Canadian your family’s sensibility might be. I think that would tend to give you a very different perspective on disproportionate impacts and problems in a holistic sense. Thank goodness for that, and thank you for being so generous with your time and insights today.

KH: It has been a pleasure chatting about this with you. Thank you, Bryan!

This conversation was first published in the Snapshot: Climate issue (vol. 29, no. 3: Fall 2023).

KATHARINE HAYHOE is the chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy and a Paul Whitfield Horn Distinguished Professor and the Political Science Endowed Chair in Public Policy and Public Law in the Department of Political Science at Texas Tech University, where she is also an associate in the Public Health program of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. She is a principal investigator for the Department of Interior’s South–Central Climate Adaptation Science Center and the National Science Foundation’s Global Infrastructure Climate Network. Her research currently focuses on establishing a scientific basis for assessing the regional to local-scale impacts of climate change on human systems and the natural environment. katharinehayhoe.com

BRYAN GIEMZA is on faculty at Texas Tech University’s Honors College, where he teaches humanities courses on such topics as AI, disinformation, and resilience. His books include Science and Literature in Cormac McCarthy’s Expanding Worlds (Bloomsbury, 2023), and he is currently developing a book on climate change and disinformation with St. Martin’s Press. bryangiemza.com

As a Texan artist with a deep love for nature,

EMMA C. SCHMIDT draws inspiration from the world around her to create hand-drawn designs that tell meaningful stories. With experience in a range of mediums, including intricate inked maps and large-scale painted murals, Schmidt has worked for clients including The Contemporary Austin, Campari, Faherty, lululemon, Deep in the Heart, and Wildsam. An avid hiker, traveler, and baker, Schmidt resides and bases her art practice in Austin, Texas. emmacschmidt.com

Header image: Trees lie fallen into the Chesapeake Bay on Hoopers Island, Maryland. They are the victims of a warming climate and eroding coastlines that may rise by as much as 6 feet by the year 2100, swallowing nearly all of Dorchester County, Maryland’s third largest county. Photo by Michael O. Snyder, 2021.