“The older I got, the more I realized that our acceptance was . . . fragile, conditional. The signs were small but telling.”

FRUSTRATION WITH MY COUNTRY came first. One evening in the early 1970s, my mom and dad debated whether to allow me and my sister to watch a tv news special about the 1963 Birmingham civil rights protests. We were kids, in the single digits. Dad, Eddie, said yea; Mom, Edith, nay. They need to learn about it some time, he said. Dad won.

They smoked their Kent cigarettes and watched us. We watched the tube. I cried. Why would white firemen aim their hoses at Black people, blast them off their feet? I asked. Why would white police officers attack Black people with dogs for walking, just walking? If they had answers, I don’t remember them.

We grew up on the white side of our town, Teaneck, New Jersey. Our friends came from two doors down, five doors down. The older I got, the more I realized that our acceptance was … fragile, conditional. The signs were small but telling. My sister was disinvited from a bat mitzvah because, the girl’s mom told my mother, they couldn’t find a Black boy for her to dance with. “Why do they do that?” one of my white friends sneered as we drove past the candy store where Black teens hung out. They? I ventured. “Oh, you’re not like them. You’re different.” I was just smart enough to know by then that in Teaneck—and in America—I was no such thing.

These little incidents were more symptom than disease, I realize now, but I didn’t have language for it then, didn’t have a name for white supremacy. I knew from just watching and living that I was not fully accepted in my own country. A phrase I learned later, “the Negro problem,” both hurt and helped. I didn’t believe I was a problem, but I certainly felt like one every day. I didn’t even need to leave home to feel problematic. I just turned on the tv, where I saw wall-to-wall white people punctuated strategically with Black criminals and entertaining Afro-American tokens. In school, History was continuous, even seamless, and very white. Black folks were absent from this narrative, except as victims, perpetrators, or rare exemplars—Crispus Attucks, Frederick Douglass, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr.—sparse sprinkles on the ice-cream sundae of white greatness.

My dad raged about white racism. He was born in segregated Virginia on the eve of the Depression, saw the family farm taken by the government to build a naval base during World War II, watched his parents struggle and fail to find comparable land because Jim Crow barred them from many desirable areas, and deployed to Germany after Executive Order 9981 declared segregation over in the US military. While serving abroad, he and his squad members—all Black men—fought off violent attacks by fellow soldiers, white men from the Deep South, who resented their coziness with local German folk. Their bone-deep racism trumped any order, executive or otherwise. “Don’t ever join the white man’s army,” my dad told me.

I felt the hypocrisy of white America and the denial as a kid, as a teen. I would always be a Negro Problem, a provisional citizen, never welcome, never home. I hadn’t yet read James Baldwin, W. E. B. Du Bois, or bell hooks, which would have helped. So, I left or tried to. In college, I took Mandarin, studied abroad in China. I graduated and moved to Taipei. I lasted six months. I became a journalist and traveled as far and as often as I could; my last major destination, at age forty-one, was Iraq. It was my third trip covering US Marines.

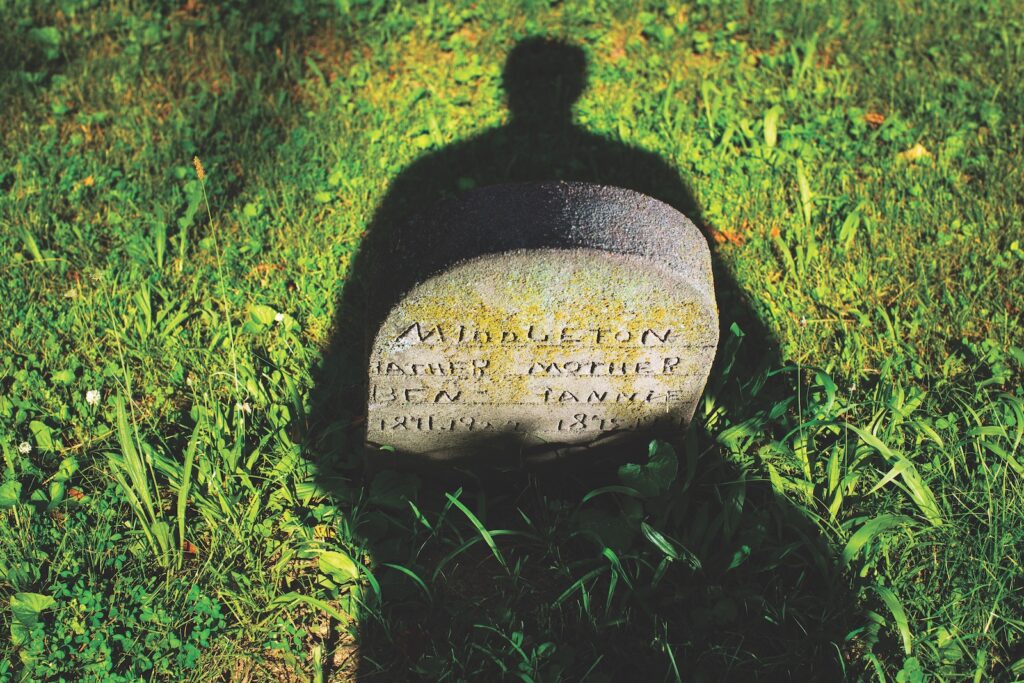

Death, my father’s, pointed me toward home. In 2011, I traveled from Brooklyn, New York, to Virginia to complete some unpleasant tasks after he passed away and to do some potentially more enjoyable investigating with Erin, my wife. We’d learned that my great-grandparents, Julia Fox Palmer and Mat Palmer, had been enslaved in Virginia. The search for documentation of their lives yielded a few amazing discoveries, among them Mat’s Union pension application and a special census done in York County, Virginia, from 1865, that listed members of Julia’s immediate family. Mat and Julia had freed themselves during the Civil War, the records seemed to show. Through them, I learned of “contraband slaves” and the United States Colored Troops, as well as Magruder, the community they helped create. Archivists and historians warned us that their paper trail would likely vanish, as it does for so many African Americans held as property before 1865. It did, but this led us, inevitably, to cemeteries. Mat’s stone, though crumbling, is the last tangible vestige of his existence. The stone next to his, which we believe is Julia’s, has been wiped clean by weather and time. I touched it, gently.

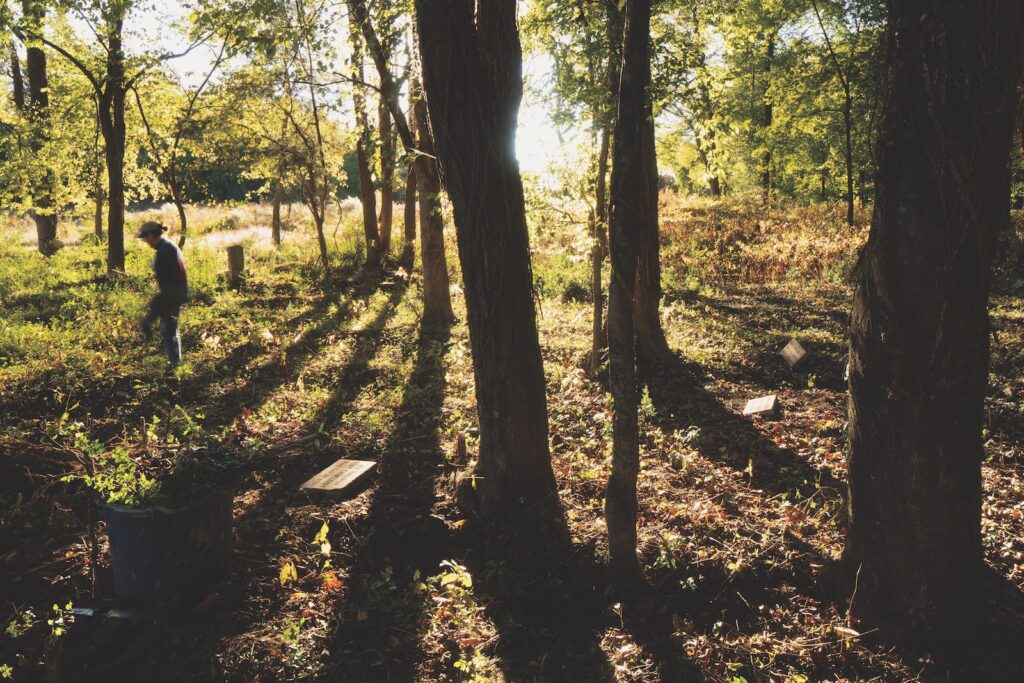

We moved to Virginia to explore this history, which to me was liberatory and grounding. Erin and I explored historic Black cemeteries across Virginia to piece together Mat and Julia’s story, and to place it in a solid historical context. So many of these places were overgrown and desecrated, while across the street or just blocks away, there’d be a pristine Confederate burial ground. We needed to hack our way in to read the inscriptions. The extent of neglect was, to me as an African American, nearly overwhelming. I knew that the same Jim Crow policies that oppressed and harmed Black people had starved our burial grounds and directed public resources to white communities, institutions, sites of memory, including Confederate monuments and cemeteries. The causes of neglect were structural, I understood. But the abject condition of these sites, of which there are thousands, still hurt.

I would write a story about it, make a documentary. I would show the damage and injustice and tell the stories of people dedicated to reclaiming these burial grounds. That’s how we found our way to East End Cemetery, which straddles the border between Richmond and Henrico County. After a day of watching and documenting a group of Boy Scouts clear brush from burial plots, Erin suggested we come back. As volunteers. While pitching in with the scouts, she discovered what it took me several more months to learn and, more importantly, to feel: this too is reclaiming hidden Black history, but with our hands as well as our minds. We went back the next week, right before Christmas 2014. We’re still going.

Brian Palmer is a Peabody Award–winning journalist living in Richmond, Virginia. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Smithsonianmagazine, Richmond Free Press, and on PBS, BBC, and Reveal. Palmer has worked at The Village Voice, U.S. News & World Report, Fortune, and CNN. He’s currently a visiting professor of journalism at the University of Richmond.