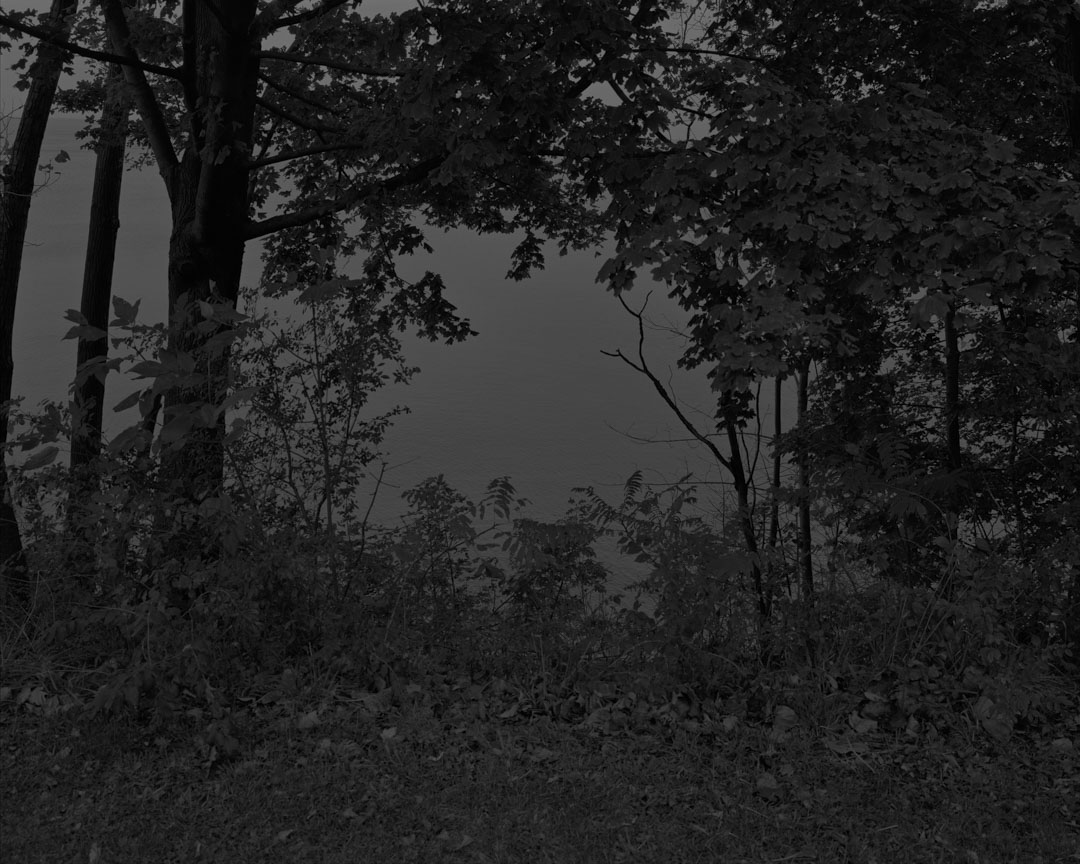

Dawoud Bey’s Untitled (The Light on the Trail) could be anywhere that is warm and wet enough to produce this tangle of plant life. But stay still in front of this photograph and really look. Somehow all of the wild growth frames an opening. And inside that rough circle, the light spirals clockwise toward the center. Linger, and that gorgeous light, the large scale of the photograph, and Bey’s eye-level angle of vision collaborate to draw you into the world of this image. Feel the roots under your feet. Hear the dead leaves crackle. Squint as you look from the deep shade toward the dappled light. Linger longer, and crisp details emerge: the smooth arch of a branch, a harness of vines, the spangle of sunlit leaves, and a haphazard mosaic of twigs, mulch, and mud. You see what is usually hidden by the darkness. But what is ahead, down the path in that bright swirl of light, remains a mystery. You see also that you cannot see. It’s a stunningly beautiful picture of a trail, but it is also a paradox—a photograph that asks you to think about the limits of vision.

Untitled (The Light on the Trail) is part of Dawoud Bey: Elegy, a monumental exhibition of landscape photographs and two related films on exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (on view through February 25, 2024) and an accompanying book published by Aperture. With this lament for the dead, Bey cements his status as one of America’s most important photographers.

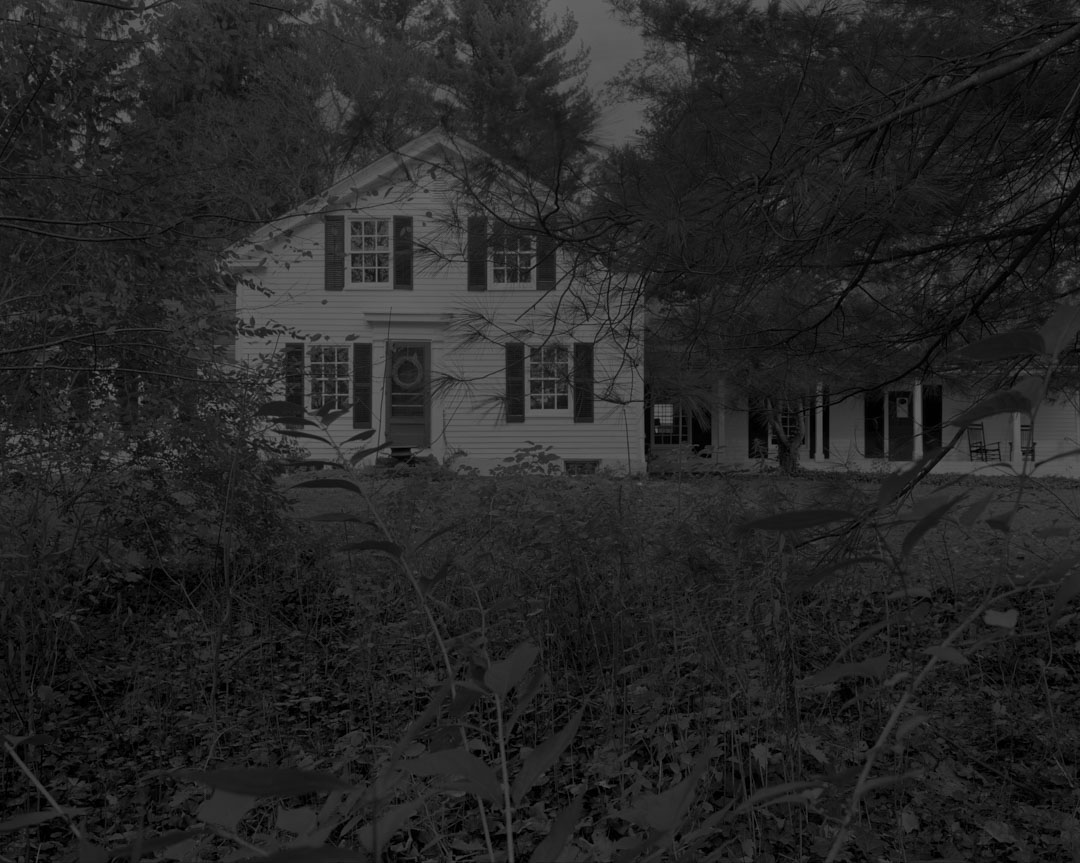

Since the mid-1970s, Bey has been known for his photographs of Black people. But a little more than a decade ago, he stopped making portraits and began instead to create images in which the Black figure is implied but not actually present. Elegy brings the three bodies of work that are the product of this new attention to landscape together for the first time. Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017) presents dark black-and-white images of underground railroad sites in Ohio near Lake Erie, places through which enslaved people traveled across the water on their way to freedom in Canada. Bey takes his title from a phrase in Langston Hughes’s poem “Dream Variations.” A second series, In This Here Place (2019), combines black-and-white photographs and a three-channel color video to imagine spaces of Black life and labor on several Louisiana plantations, including Evergreen with its twenty-two surviving slave cabins. This time, Bey uses a phrase from Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved for his title. The most recent series, Stony the Road (2023), commissioned by the VMFA, uses black-and-white photographs and a two-channel, black-and-white video to picture the Richmond Slave Trail, the surviving few miles of the path enslaved people walked from boats that docked at Manchester to the slave auction houses in Shockoe Bottom. Bey finds his title in “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Black national anthem and a song whose lyrics were written by James Weldon Johnson.

These choices reveal the photographer’s debt to Black writers and their long tradition of imaginatively engaging with Black history. Black visual artists have always been concerned with Black life, but some began to take up the Black past in earnest in the late twentieth century. Photographer Carrie Mae Weems is an important pioneer here, with her Sea Island Series and subsequent work about African and African American history. Today, Black artists make work about history as often as they do about contemporary Black life. Bey has made his own intentions for this new landscape work clear. “I’m interested in how landscapes of history are also Black spaces,” he has said. “These three projects engage the idea of the way in which history enacted on, with, and through Black bodies has a kind of residue that clings to the land.”

Making photographs about subjects that cannot readily be seen is not a new move, but it is still a radical proposition. Bey cites the example of photographer Joel Sternfeld, his mentor and teacher at Yale, who published a 1996 book of photographs of seemingly ordinary sites where people previously committed horrific crimes. But over the last decade, a growing group of Black artists and scholars, including Saidiya Hartman, Teju Cole, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, and Tina Campt, have produced work that explores the limits of photographic vision in order to question photography’s problematic history in relation to Black people and to model alternative ways of seeing. Bey began exploring these issues with his 2013 body of work, Birmingham Project, which memorialized the four young girls killed in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing and two boys killed in the aftermath by using portraits of contemporary Black children and adults to suggest the lives the victims should have been able to live.

As with this work in Alabama, Bey traveled to actual historical sites to make the landscape photographs in Elegy. In rural Ohio, near Lake Erie, he found a handful of antebellum houses that would have been there when the Underground Railroad ran through the area. Down a road lined with live oaks in rural Louisiana, he explored the homes where enslaved people once lived. But on the Richmond waterfront, nothing related to the transport and sale of enslaved people remained.

Part of the problem at all three of these sites is that more than one hundred and fifty years have passed since emancipation, but an intentional erasure is also at work. Americans have preserved many historical buildings and landscapes from the antebellum era, while others have been neglected. Understandably, in the aftermath of emancipation, many Black people worked to distance themselves from anything connected to slavery. White people, in turn, had their own reasons for neglecting, destroying, or occasionally preserving these sites.

What has happened in these places must surely haunt our own present. The repeated sundering of intimate and familial relationships and deep ties to places and communities that enslaved Black people endured must have an afterlife. Bey’s challenge is to give this absence a presence. What does it look like to photograph so many layers of loss?

Many of the photographs in this exhibition are stunningly beautiful. Conjoined Trees and Field, from In This Here Place, presents two trees with scarred trunks that have somehow grown together in an elegant form of arboreal solidarity. “Cabin and Light,” from the same series, depicts the shadows cast by the eaves, beams, and posts of an unseen porch. Untitled #13 (Trees and Reflections), from Night Coming Tenderly, Black, reveals a cold lake reflecting its own bank and wooded shore in its dimpled surface. Here, as in all of the photographs in this series, Bey has scrambled time, darkening an image he made in the daytime in order to capture a level of detail that would have been impossible if he had shot at night. In this way, Bey evokes a superpower—the ability to see in the dark—that anyone running for freedom might need.

In the past, the few American photographers who took up “history” as a topic often used a straightforward, documentary approach. Perhaps the most well-known of this type were made by photographers working for the Farm Security Administration, who, for a time, were instructed to create images that revealed the backwardness of the South, including places where people seemed still to be living in an earlier time.

Working almost a century later, Bey takes a much more conceptual approach. What is pictured here is not exactly the particular Black past referred to in the wall text. It’s not the same roof that sheltered an enslaved family—those shingles have long since rotted. It’s not an actual house that served as an Underground Railroad station—Bey has said in interviews he substituted a more interesting one. It’s not the same trees or the same vines or the same dirt where enslaved people crept quietly toward the border or stumbled in shackles on legs not accustomed to land. It’s probably not even the same path by the James River, given the way rivers flood and shift their banks. It’s not that past, but it is a past, some now-gone moment when the artist stood there and set up his camera lens. Bey mobilizes the formal and material qualities of photography to encourage you to feel the past as your present, too.

In a profound sense, every photograph is about the past. Light has bounced off something in the world onto some light sensitive material, and the photograph fixes that occurrence as a still image, a fragment of time ripped from the flow and carried into the future. In this way, as theorist Roland Barthes long ago argued, photography unsettles the flow of time. Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa explains the complexity of this rupture by dividing it into three categories: “time as expressed by the image itself,” “the relation of the image to its historical moment,” and “the afterlife of the image as it passes through time.”

What Bey’s last decade of landscape work does is expand our understanding of the image’s relation to its historical moment to include not just that point in time at which the image is made but also that point in time that the image is trying to recall to that present. In other words, Bey is trying to photograph a present and a past simultaneously.

Of course, in an important sense this is impossible. But on a conceptual level, Bey works to activate the many intersections between the medium of photography and the arena of human knowledge known as “history.” Both historians and photographers manipulate traces of the material world. For historians, this thing is a document, a ruin, a shard of pottery, a headstone, or even a photograph—what historians call evidence, the physical traces of the past that establish the facts. For photographers, this thing is whatever material is there for light to bounce off of in order to register its surface. But this is just the beginning of what it takes to produce a photograph (or a history). The historian and the photographer also add culture. They select, crop, or flatten these traces, arrange them into sequences, and add words of explanation. In the process, they give them meaning by turning them into a story. The objective, the exterior, and the material mix with the subjective, the interior, the social and cultural. When artists photograph “history,” they double these effects. History and photography become metaphors for each other and for the interconnections between these binaries.

The paradox of Bey’s Elegy is that his photographs are most powerful when they contain the fewest physical traces of the era of enslavement, when you stand there on the shore of that dark water that could be anywhere and look for a way across. Here—in person at the VMFA and in the book—the most conceptual photographs are surrounded by text: an interview with the artist, a curator’s statement, scholarly essays. They are also placed into an arrangement that includes less conceptual images. All of these things work together to nail down a particular interpretation. But as Wolukau-Wanambwa and the critic David Campany persuasively argue, “for those interested in the image, particularly the photographic image, indeterminacy is always to be reckoned with, aesthetically, and politically.” Photographs are always “less knowable than we may wish or need them to be.”

Bey invites careful viewers to enter the space of these images. He asks them to think of themselves as inhabiting the condition of being a Black person in the time-period of enslavement and enduring forced labor, family separation, and flight. He asks them to grapple with the fear and the terror and to try to plumb the deep layers of loss. He asks them to see and to feel this particular history and to identify with the people who lived through it. How a viewer who answers this call handles the painful act of imagination at its core will vary drastically depending on differences of race, genealogy, ethnicity, nationality, and individual personality.

Once a museum invites viewers into an artist’s work, what they will make of what they see is to some degree up for grabs. Some might imagine other bodies of water, other fields, other banks, and other modes of being under those trees: other people and other histories. This capaciousness—this invitation to imagine and respond and feel, and also to think—is why we need art.

This essay is part of our Shutter art and photography series. Dawoud Bey: Elegy, an exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, from November 18, 2023, to February 25, 2024, and a 2023 book published by Aperture.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a 2018–2019 Carnegie Fellow. She is the author, most recently, of In the Pines: A Lynching, a Lie, a Reckoning, a history of her grandfather, a Mississippi sheriff, and white Americans’ inability to reckon with the history of white supremacy (Little Brown, 2023). She has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Slate, American Scholar, and Southern Cultures.Header image: Untitled #24 (At Lake Erie), from the series Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017, Dawoud Bey (American, born 1953), gelatin silver print. Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Image © Dawoud Bey.