Almost exactly two years ago, on October 31, 2022, one month after suffering a stroke on a flight home from Oakland, where he had been performing, Patrick Ambrose Haggerty, the visionary seventy-eight-year-old songwriter, singer, and embodiment of the band Lavender Country, died at his home in Bremerton, Washington. Beside him on both passages was Julius “JB” Broughton, his husband of seventeen years, steadfast partner of more than three decades, and, since the Lavender Country renaissance on which we all embarked together in 2014, his champion and self-proclaimed “merch girl.”

Patrick was my friend and collaborator as well as one of the few people in my life I can unironically call a hero. When I cold-called him back in 2013 to inquire about reissuing his landmark 1973 album Lavender Country, generally acknowledged as the first openly gay country music record, neither one of us could have imagined where it would lead us. At that time, music was largely a private practice for Patrick; he was playing occasionally at nursing homes and felt that Lavender Country was in his past. I’d just welcomed a son into the world, and Patrick and JB watched him grow up, showering him with affection and gifts (books, a David Bowie album, costumes) from afar and when they passed through on tour. His songs and his example—as an artist, activist, and father, as a human being moving through the world, fighting hatred and cruelty, trying to raise a righteous voice for love—continue to inspire and impel me and his many friends and fans. An irrepressible raconteur, he was never at a loss for stories or words, but for me, two small words—his extraordinary father’s moral imperative—sum up much of what he stood for: “Don’t sneak.”

It’s fitting that Patrick left us on Halloween, our final commonly observed national holiday to celebrate the ritual inversion of the social order, when we give ourselves license, through the performative process of masking, unmasking, and mischief-making, to violate social norms and assume new identities, if only for one night. His subversive embrace, with his music and more broadly in his life, of pageantry, camp aesthetics, and absurdity—a word he deployed to describe his belief as a young man that his songs might find the audience and recognition that eluded him for decades—was pure Halloween. (He also loved all manner of desserts and sweet treats, indulgences that he referred to, with his characteristic sense of outrageous humor, as “fatties.”)

But Patrick’s radical, liberationist politics and dauntless activism were no mere mask. As a career social worker, organizer, community leader, and mentor to musicians across the country, he fought and proudly marched, purple cowboy boots on the pavement, for the oppressed—a category that for him potentially included anyone, regardless of identity. (In 1971, he even spent time organizing for gay rights in Cuba, a story that remains to be told.) The goal, always, was solidarity among the marginalized, comradeship between all factions of poor and working-class people. Only then, as he shouts in “Waltzing Will Trilogy,” can we “rise up and rip this goddamn system down / ’Cause there ain’t no hope till it tumbles to the ground.”

The following essay is an excerpt from a longer piece, the introduction to the “Music and Protest” issue of Southern Cultures I guest edited in 2018, titled “Private Press Protest and the Southern Imaginary: What I Learned from Gay Country, Communist Disco, and a Choctaw Poet’s Sermon on Immigration.” Sadly, little has changed since then. At this precarious and perilous moment in American history, with white nationalism ascendant, a fascist, felonious clown returning to the Oval Office, and so much at stake for the disenfranchised, Patrick would only have screamed his message louder. He always told me he intended to “drop dead” onstage.

A staunch Marxist, iconoclast, and cynic despite his strict Catholic upbringing, I doubt Patrick believed in any sort of conventional notion of the afterlife, binary or otherwise (though who knows what he hoped for in his heart of hearts, the man was full of surprises). But he did profess his faith in a heterodox heaven on earth, the egalitarian and unabashedly idyllic contours of which he described in song and limned in paint. He even named his band after it.

“Come out, come out, my dears, to Lavender Country,” he sang. “Just spread your spangled wings and fly.”

Brendan Greaves

November 6, 2024

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Rise Up and Rip This Goddamned System Down!

The Revolution started out right

Black Panthers were leading the fight

The Lords were in the left flank

The women drove a Sherman tank

And the workers were a hunk of dynamite

A battalion of Gay men brought up the rear

Packing two grenades in each brassiere

Every purse was filled with mace

Carbine rifles trimmed with lace

Them campy Gay guerillas knew no fearBut the liberation forces got uptight

They screamed, “You fags ain’t got no human rights

We think you guys are sick’

Cause all you want’s a prick”

And while we scrapped, pigs stole the whole damn fight

That was the end of the revolution, my friend

’Cause all of us are going to the pen

They’re rounding up the Blacks

Then they’re after Gay folks next

So I’m Back in the Closet Again—Lavender Country, “Back in the Closet Again”1

When I make banana cream pie, I use a handwritten recipe given to me by my friend and hero Patrick Haggerty, who learned it from his mother, the matriarch of a family of ten who lived on a tenant dairy farm in the rural, working-class community of Dry Creek, Washington, on the northern edge of the Olympic Peninsula. The association between Patrick and pie has always seemed apt to me, as Patrick’s radical artistic legacy represents the aural equivalent of a banana cream pie in the face of the country music establishment. In 1973, Haggerty, a fearless first-generation gay liberation activist, wrote and recorded with his band Lavender Country what is widely recognized as the first openly gay country music album—and cited as such by conservative Nashville institutions such as the Country Music Hall of Fame and CMT. (My record label Paradise of Bachelors reissued it in 2014.)

At once a scathing indictment of the injustices perpetrated against the LGBTQ community, a proud proclamation of gay identity, and a love letter of bracing intimacy and eroticism, the album radically appropriates the signifiers of the conservative country genre, queering its heteronormative vocabulary into a deeply personal language of love and liberation. The songs, whose deceptively fragile sonics—the ramshackle recordings often sound on the brink of shattering apart with shuddering sorrow and rage—belie their galvanizing ferocity, deploy biting humor and brutal heartbreak alike to claim a corner of country music for queer voices and queer narratives. They still sound revolutionary forty-five years later. “Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears”—one of the indisputably great country song titles of all time—begins with a lyric that shocks even today: “I’m fighting for when there won’t be no straight men/’Cause you all have a common disease.” The line is ambiguous: is it an unsettling pre-AIDs crisis curse or a clinical diagnosis of heterosexual hate as plague, or both? “Your sexism’s a broken record, record, record,” Patrick sings, that’s “been screeching for ten thousand years.” Straight “daydreams are rotten” and withered, a “rose begging dew”; Haggerty himself remains “haunted.” A brave Seattle DJ lost her FCC license for playing the song shortly after its release.2

The ten songs on Lavender Country land at some ethereal, subversive psych-folk nexus of the Flatlanders, the Holy Modal Rounders, and the Cockettes, with a pure protopunk heart that reveals itself through the sometimes shrilly histrionic (though deeply charming) singing, the crude but effectively forceful strumming, the sometimes gawky arrangements, and the resolutely lo-fi recording quality. Despite its proud amateurism, the delivery devastates with its sheer candidness. (“When I came out, I came out a screaming Marxist bitch!” Patrick reflects.) Haggerty rails against the trap of “Straight White Patterns” (which force the community to “surrender to our gender one more time”); he recounts the institutionalization, incarceration, and murder of gay men in “Waltzing Will Trilogy” (exhorting us to “Rise up and rip this goddamned system down!”); and depicts both the panting thrill and indelible sadness of anonymous sexual encounters and surreptitious relationships in “Gypsy John,” “Georgie Pie,” and the gorgeous lament “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You.” (Haggerty’s astonishingly acute and empathetic dairy farmer father’s abiding advice to a teenage Patrick in 1960, following his be-glittered drag appearance in a school cheerleading competition, was, “Whoever you run around with, don’t sneak; be proud of it.”)3

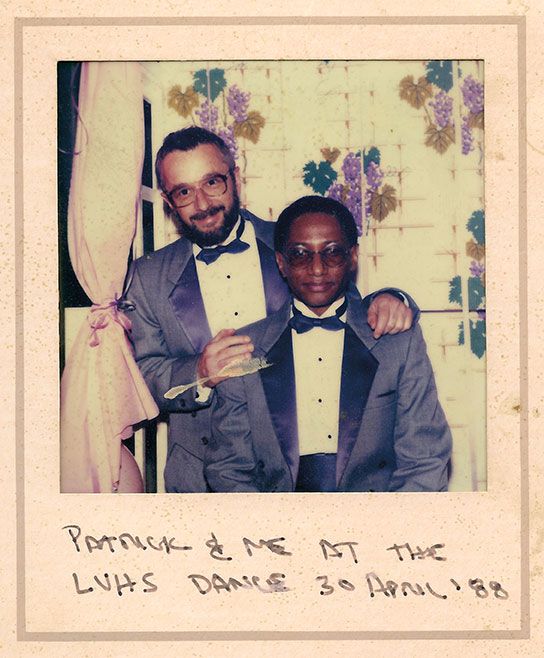

The protest strategy was intentional, a planned program of documentary-style songwriting in the service of the nascent post-Stonewall gay liberation movement. “I’m going to write personal and political songs,” Haggerty remembers thinking to himself, “all about the issues we were talking about at the time: having sex with other young people, ending up in prison, being in psychiatric institutions, having really lonely sexual lives, cross-dressing—just being proud of who we are.” The ambitious goal was the dissemination of what Haggerty refers to as The Information—stories and songs about “what it means to be gay, how to be gay”—to other young people starved for context and comfort. With the assistance of colleagues at the Seattle nonprofit Gay Social Services, Haggerty pressed 1,000 copies of the LP and distributed it by mail order through underground gay publications and bookstores, specifically targeting people in isolated rural communities through a partnership with RFD Magazine. In 2017 Beyoncé commanded listening ladies to “Get in formation,” a lyrical homophone of “Get information”; in 1974 Patrick was doing both, organizing the movement through action and art. He went on to pursue a long career in social services, including working for the City of Seattle Human Rights Department and running for Washington state senate on a “black-led, multiracial, pro-gay” New Alliance Party ticket with Nation of Islam members in 1988.4

Haggerty is not southern—he is proudly a product of northwestern culture, specifically the Olympics and Seattle—but he grew up immersed in the music of the South, “listening to Patsy Cline and Hank Williams, Eddie Arnold and Slim Pickens, that crew” on Canadian radio and at dances and concerts at the local grange hall. “We often forget that gay people come from everywhere,” he reminds us. Likewise, “Country people, and country music, come from everywhere.” Today, although Haggerty feels that in “kicking down the closet door” of country music, he permanently excluded himself from a career in Nashville, the country music establishment has finally, recently begun tentatively opening its doors to LGBTQ voices. But it is important to recognize that the pioneer was not a native of the South, or the Southwest, or even Southern California, country music’s traditional domains, but grew up on the edge of an American Indian reservation on the Canadian border.5

Haggerty used the form of country music as a vehicle for The Information because country music was what he knew and loved, and because it is so well suited to storytelling and melancholia, if not necessarily radical leftist politics. The original lineup of Lavender Country wasn’t southern either—and notably included a lesbian (Eve Morris), a gay man (Michael Carr), and a straight man (Robert Hammerstrom)—though these days Haggerty employs regularly rotating pickup bands for each tour. Band members represent a coalition of likeminded “punkers” (as Haggerty deems them), ranging in age from teenagers to seniors, from a variety of racial, cultural, class, and musical backgrounds. When in Nashville, Patrick is supported by country-psych band Promised Land Sound, comprised of straight white male musicians one-third his age. “That’s very effective; it sends a powerful message,” he tells me. “If these Nashville kids are enlightened enough to get with the program, why can’t you?”6

A rewrite of Texan star Gene Autry’s signature hit “Back in the Saddle Again,” a mission statement of macho cowboying and camaraderie, “Back in the Closet Again” is a deft act of appropriation and infiltration that inverts the confident machismo of the original song with resignation about Haggerty’s bitter feelings of disenfranchisement from within the freedom movement. It’s the only song whose lyrics appear on the back jacket of the original LP, as opposed to the insert, likely because it offers a telling statement about Haggerty’s views about the necessary solidarity of human rights struggles, the ways in which class struggle—“the Revolution”—should transcend race and gender and sexual identities but ultimately does not. (It resembles a disillusioned activist’s weary rejoinder to Phil Ochs’s anthemic “I Ain’t Marching Anymore.”) The song “Lavender Country,” which closes the album, provides a more sanguine, psychedelic vision of unity, conjuring an Edenic space where transgressive gender and sexual identities achieve a beatific, bacchanalian grace in variegation. Haggerty imagines Lavender Country as a palimpsest of places and identities, made up of nostalgia for his homeplace and his supportive parents—“Every time I go back there, I just sit there and bawl, it’s so gorgeous”—and of hope for a place free from oppression where you can “spread your spangled wings and fly.”7

Rehearsing for the first Lavender Country comeback concert in Los Angeles, in 2014, Patrick presented me with a landscape painting he had made, great snow-capped peaks rising behind a rushing mountain stream. “That’s Lavender Country,” he told me. “That’s where I come from, where my music comes from, where everyone in this room comes from. And it’s where we’re going.” In the age of HB2, the existence of Lavender Country in the American South, the home of country music, remains unrealized and undiscovered.8

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Brendan Greaves is founder and owner of the record label Paradise of Bachelors, which reissued Patrick Haggerty’s 1973 Lavender Country album, and the author of the book Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen. A folklorist, essayist, and lapsed art worker, he studied at Harvard and UNC, and lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, with his wife, Samantha, and son, Asa.

NOTES

- Lavender Country, “Back in the Closet Again,” words by Patrick Haggerty; music by Gene Autry and Ray Whitley, Lavender Country, Gay Community Social Services, PC-160, 1973.

- Lavender Country, “Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears,” words and music by Patrick Haggerty, Lavender Country, Gay Community Social Services, PC-160, 1973.

- Patrick Haggerty, in conversation with the author, 2014; Lavender Country, “Straight White Patterns,” “Waltzing Will Triology,” “Gypsy John,” “Georgia Pie,” and “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You,” words and music by Patrick Haggerty, Lavender Country, Gay Community Social Services, PC-160, 1973; Patrick Haggerty and Brendan Greaves, “‘Spread Your Spangled Wings and Fly’: An Oral History by Patrick Haggerty, in Conversation with Brendan Greaves and Christopher Smith,” Lavender Country [liner notes], Paradise of Bachelors, PoB-012, 2014.

- Patrick Haggerty and Brendan Greaves, “‘Spread Your Spangled Wings and Fly,’” PoB-012, 2014; Patrick Haggerty, in conversation with the author, 2014.

- Haggerty and Greaves, 2014.

- Haggerty, in conversation with the author, 2014, 2018.

- Lavender Country, “Back in the Closet Again,” PC-160, 1973; Lavender Country, “Lavender Country,” words and music by Patrick Haggerty, Lavender Country, Gay Community Social Services, PC-160, 1973; Haggerty and Greaves, “‘Spread Your Spangled Wings and Fly.’”

- Haggerty, in conversation with the author, 2014.