“The longing for home never ceased, and the sojourn Down South would develop into a summer tradition.”

For most of my young life I was denied the truth about my southern Black heritage, and the urbanized Americanized culture around me was teaching me to be ashamed. Of course, this dark skin, these pronounced and molded features, resemble some of the most ornate ceremonial masks of the old world, and the desire to adorn myself is an ancestral call I answer every day. Now, I take pride in that lineage, the heritage that is often siloed into the sole narrative of the cross-dimensional sufferings of those who experienced and survived the middle passage and those dozens of generations that endured indentured subjugation, followed by legislated terrorism in the southeastern regions of the United States. The latter fact, I think, is what my immediate ancestors impressed on my psyche, these myths about the South being a place one needed to escape from, one that needed to be modernized, minimized, and forgotten.

Girl, you so country. His ole country ass. They so slow Down South. These admonitions brought sweet camaraderie to the generations that followed those who had to abandon their rich cultural and social lives to become migrants in a nation they built. We shared a common familiarity that southern so-called country living was in our collective past and would remain there. I think these common figures of speech shielded us northern descendants from the pleasures of community, the ones deserted because of sharecropping, Jim Crow, and growing economic despair. The mourning of a life in the sun, in the soil, amongst one another. The truth is those circumstances only shifted some. My people’s Georgia red clay and Alabama air were replaced with the city sorrows of sticky cement and polluted skies. Often, I imagine an alternate life—one where my coast is the Gullah, or my streams are the Gulf, and the lakes, rivers, and reservoirs are warmed by the radiant nature of the deep American South.

My biological father migrated from the South in the 1970s, courtesy of the United States Navy. He and my mother met in 1980 at the funeral of her father, a southern man who made a name for himself in the once-Black hamlet of New Cassel in the once-monied white suburb of Westbury, Long Island. My mother’s father was the official unofficial liquor distributor on the days blue laws made it impossible to get booze, and of course on the days when it would be easier to get a bottle of cold wine sold on credit. This enterprise endeared him to the residents of the suburb. His funeral was attended by many.

My grandfather is one of the many stars in the constellation of my Black southern heritage. The lore from a story my mother often shares, the details a slightly different sketch drawn from another’s memory. Sometime in the early 1930s, Rayford Robinson was tried by a jury of white men holding ropes in front of a tree for an unknown and arbitrary indiscretion. How he managed to snuff the potential of his death in that moment remained untold but likely had something to do with how he made his way quick fast to Long Island with the promise of working on a potato farm. Around the same time, my grandmother, Ethel Rivers, ventured north in the wake of her being fed up with gendered and racialized brutality. Both of my maternal grandparents were spurred by threats on their lives to make roads up north. There they met, and their home became the origin story for my southern family’s Black life in the North. Their children would abandon the life of the suburbs for the promises of the City a short train ride away.

While my paternal grands remained on their sprawling two-hundred-acre farm, two-thirds of their thirteen offspring made new lives above the Mason–Dixon Line, in the Empire State. Who knows of the promises of steady work with upward mobility and the glamour of the city sought out by my young aunts, uncles, and teenaged father? According to one of my aunts and confirmed by my mother, my father had grown tired of the shadows of Jim Crow shading the bright light he sought for his future. Yet, their longings for home never ceased, and the sojourn Down South would develop into a summer tradition.

You look just like yo Daddy. My father was the absent parent, the one who, during my early childhood, lived in another borough, less than ten miles away, but then farther and farther down the coast until he reached his final resting place. And still, when he lived close, he was someone I saw so infrequently that I had no presence (no room, clothes, books, toys, hair products, favorite juice, or candy) in any of the homes he lived in with his family. This tension was palpable and reinforced my feelings of being a foreigner amongst relatives—if you can’t belong to your own father, then just who do you belong to? It was strange, our time spent together, rarely just the two of us for longer than the car ride from my mother’s to his place or to my aunt’s or uncle’s. There, we would arrive in time for dinner, followed by my listening to the grown folks shooting the breeze, smoking Kools or Camels, and drinking beers. Everyone southern, living their lives up North. It bored me and never really brought us two much closer.

I felt like an outsider observing these people I was often accused of resembling. Their twangs and tones were so different from the fast, flippant speech I was encouraged to pattern. Sitting on sweet Aunt Maggie’s smoky, printed-plastic-covered sofa, I would sneak a look at photos of my cousins to steal glimpses into the mysterious life that existed before I was born. The boys with their shirts off in the summer, the girls posing with my older sister. There was never a plane I could imagine where these worlds came together. But they did, these photographic hints of summers spent Down South. A family crafted before my birth. And there I was, growing up in its wake.

These gatherings in Queens, Brooklyn, and Long Island never brought me closer to my father, but what emerged from the distance between us was a love for travel and for the scenery of a new place. It was exciting speeding down the various parkways linking New York City in his flashy cars, him blasting the rap music I loved, music that my mom and stepdad didn’t seem to understand. But when my father started to deepen his Islamic practice and espouse modesty, he drove a broke-down-ass Ford Taurus, sharpening my embarrassment at being seen with him. His beliefs extended to his gift-giving during my preteen and teen years, and his fanciful splurges slowed. Rather than sneakers and emblemed clothing, he offered an unsolicited Ayat from Surahs I’d never read in the several Qur’an that sat on the top of my bookshelves. Still, as he became more frugal and pious, and as the distance between us continued to expand emotionally and geographically, in his presence I couldn’t help but feel the thrill of escape. He had fashioned a new life for himself away from everything that was familiar to me, and through him I saw that I wasn’t destined to be confined to the life, people, or neighborhood that shaped me, nor the poverty that threatened to trap me. Our time was possibility. I couldn’t name this desire to see more of life outside the threshold of what was familiar. Despite his prudent spending, my father was the first to offer me a chance to venture beyond the city and know myself elsewhere. Some of my earliest journeys flying solo were sponsored by him, allowing me to be myself beyond the watchful gaze of my mother.

Family reunions with my father were fraught with many conflicting emotions. For one long weekend in the summer, every other year, I would travel to different locales Down South, like Jekyll Island and Myrtle Beach, to spend time with my father and his people for the Toomer family reunion. In the city, I was teased for my last name, and even now, the shape of embarrassment forms the mumble whenever I say it, undoubtedly forcing me to repeat myself. The feeling is more muted now, but there all the same. The name would be displayed in neon on the family’s reunion shirt, the same design every year: a tree, the name toomer sprawling above it, and the names Pinchback, Eubanks, and two others I can’t remember anymore fruiting from the branches of the tree. The idea of wearing a shirt with our name printed boldly on the front made my preadolescent and teenage self writhe with discomfort. Even so, I wish I’d kept at least one.

It would take some time for me to relax in a home with my father and his wife. But a meal served from the comfort of an aunt’s house, or her double-wide or her villa (if we were at a resort), restored my senses and grounded me. And at least Down South I wasn’t the only child, and I had kin around my age. Hearing my cousins speak with their drawls, with their familiarity among one another, listening to OutKast, knowing the ins and outs of our grandparents’ house, knowing all my aunties’ names, never scared of bugs or the outside for that matter, there was a knowing in their voices that I longed for. Obviously, I belonged, but the distance, the icy coolness that I learned from New York life, the only one I’d known, kept me from understanding that I was southern too. Just how I am African. How I am native.

In the Spring of 1949, my mother was born in Long Island, in the same town where she would meet her husband at her father’s funeral. Her childhood was one spent filling in the gaps that the Jim Crow era made for her parents. Reading and signing promissory notes, bank statements, negotiating simple harms enacted by racist white educators in desegregated schools (a teacher once suggested that her parents “beat” my mother to correct her weak math test scores).

I believe my mother came to contextualize southern life for all that it denied her parents. It’s unsurprising she held little if any romance for the South of the mid-twentieth century. In response to my girlhood inquiries about my grandmother’s life, my mom recalled the memory of attending the funeral of her maternal grandmother. When my mother was four or five years old, she was held up over the casket to witness this mysterious woman who had the face of her mother along with distinctly long silver braids silhouetting her petite frame. Other than that, my mother’s experience of the South before adulthood would be by proxy. There always seemed to be an uncle, or a cousin, or a Mr. and Mrs. So-and-So showing up at the door of her childhood home, fleeing some drama from the South, and my mother was tasked the additional labors of the house my grandfather so easily opened to the transients on their paths up north. From the stories she tells it wasn’t all dishes and laundry—many of the guests were interesting and funny. One guest, who dressed in custom-tailored suits, wore his kinky hair processed in a slicked-back parted coif, and drank good liquor, fell asleep in the basement while he was smoking. After the cat alerted my grandfather, he, my mother, and Gramma discovered the man still half asleep (probably drunk) with his chemical-ladened hair and the mattress up in smoke.

Some guests brought their troubled ways and even their roaches in their suitcases. I get the sense that some of these visitors were intrusions upon an already trying youth. My mother had to grow up fast, with aging parents who didn’t espouse the values of many of her friends’ younger, more citified parents. By the time of her adolescence in the early 1960s, many of the families that formed the tight-knit Black community, at the Baptist and ame churches in the hamlet, had chosen to escape the cruel and intentional poverty of a segregated city. They seemed to be on a later trajectory of Black migration—distanced from the rural farm life by decades, even a generation—and fed up with the decaying tenements and absent landlords of Harlem or the pressures of homeownership in one of the city’s five boroughs. All the musicians she loved of the 1960s and ’70s had long abandoned their southern drawls and replaced them with posh, made-up accents, becoming national and even global figures. From my mother’s childhood point of view, those in her gaze had left the South behind them, a tarnishing mirror of the past.

Yet, the desire to visit and explore the mysteries of the family members who chose to remain in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and Tennessee flamed wildly in her heart. Her stories shaped my romantic hopes of adventuring to the South. In her twenties, my mother drove over the Chattahoochee from Georgia to ‘Bama, visiting her great-aunts and first cousins. She ate like a royal: fresh peas, beans, and collards from gardens just out back; tender, fragrant white rice; earthy chitlins and spiced sausages rendered from the pig just back from slaughter; chicken fried golden. Then and there, she lived the histories of our family. I sensed that as she traveled in her ancestors’ sacred lands, she began feeling her way through that younger version of herself, and her life in the North came fully into focus—a life with gratitude for the littlest things, like indoor plumbing or the corner store.

I have my own dreamy romances of southern life. One where my neighbors and first friends are my cousins, with big Sunday dinners after church, posing for photos together at whoever has the biggest house on Easter. Where it’s always sunny and warm, and folks are rejoicing. My sister and mother and I all go Down South together every year to see my gorgeous maternal family, all united by our shared ancestors, Hannah Hawk and Ananias Robinson née Sweet. There is a sense of hope and wonder on our little family’s adventures to Georgia and Florida to visit our peoples. Hope because our family’s existence is proof of our resilience despite the reality of the plantationocene. Living as an affirmation is fascinating. Black survival.

I often wonder how we survived. How we remained so spirited, how we expressed our sorrows and rage, how our drinking, or our working, or our churchgoings consolidated the physical and spiritual dissonances we face because of our familial and larger Black American heritages. I marvel that the lives lived Down South, at least right now, at least with the privilege my extended family possesses, seem grand: big homes, big cars, big laughter, big gardens with bigger collards and okras, and of course the big gatherings for a family reunion, a wedding, or a milestone birthday—and especially for the achievement of a Black woman living on despite the many threats to her mortality. Coming Down South for me has always been a celebration. In comparison to this life up North, it’s abundant, and I see the why and the how of choosing to stay where our ancestors found themselves or, more often, where they freed themselves. There is and was freedom in staying.

One summer, in the 1990s—after an eventful weekend family reunion with my dad’s side of the family in Georgia—I came back home to New York with a perfected and natural (at least in my child’s mind) southern drawl. I remember my mother peering at me strangely as she questioned me, and I blurted out “I can’t stop talking like this.” Me: the elementary-school-aged girl accused by friends in the neighborhood and the three other Black girls in school of “talking white” or sounding like “a valley girl.” My accent had been influenced by regional inflection and cadence, by the voluminous Long Island accents of my mother and stepfather, by the 1990s’ hip-hop swagger in my older sister’s voice, and by all the white TV shows and movies I watched. But in that moment, even after stifling the embarrassment I felt when my southern cousins caught my new twang and roasted me about it, I felt like I spoke in a way that belonged to something greater than what was immediately around me. My rendering of a southern accent freed me to be more of something that I couldn’t articulate then but now understand as an unabashed Blackness. There was nothing unsophisticated about saying finna instead of bout-to when speaking of an errand or task. It was common and instantly understood. Speaking slower meant I could parse my words, give them a new flair, and be heard. My new accent grew from deep roots to a mother tongue. The accent didn’t last longer than a few days, but the memory has stuck for years.

Understanding my southernness and making the distinction that it’s a partial identity I cultivated in the North, its alleged opposite, has given me permission to be more fully myself. Thinking of myself as a citified northerner who was in some way superior to others, which is an old-school Mayflower wasp opinion, kept me from connecting to acts and sites that could bring me closer to my ancestors. Being in nature and being delighted by the outdoors expands and beautifies the images and narratives often assigned to my enslaved ancestors. So many of us brought the traditions and ancient knowledges of the land to the grounds of our homes—our accents, phrases, forms of reading, our codes, a hybrid of the colonial language, of the indigenous marriages of speech with our mother tongues. My family often makes celebrations out of the most mundane occasions. We find pleasures in casually being together, eating, drinking, laughing, singing, and dancing. These acts, and how I witness them, erase the false contempt for the rural farm life of Perry, Georgia, or the rigors of survival in Eufaula, Alabama.

Going Down South is that going-back-home feeling, one often shared when folks in the diaspora visit the mother continent. Setting foot on South African soil felt as familiar to me as running in the fields of my paternal grandparent’s farm at sunset, dodging the lightning bugs whose magic glow mystified me. I was a city kid, still scared of bugs. They flew and flickered on the land my ancestors reclaimed for a family that has since splintered into white, white-passing, light-skinned Black, and us—we who wear the mark of our continental African ancestry and aren’t working through generations to erase it.

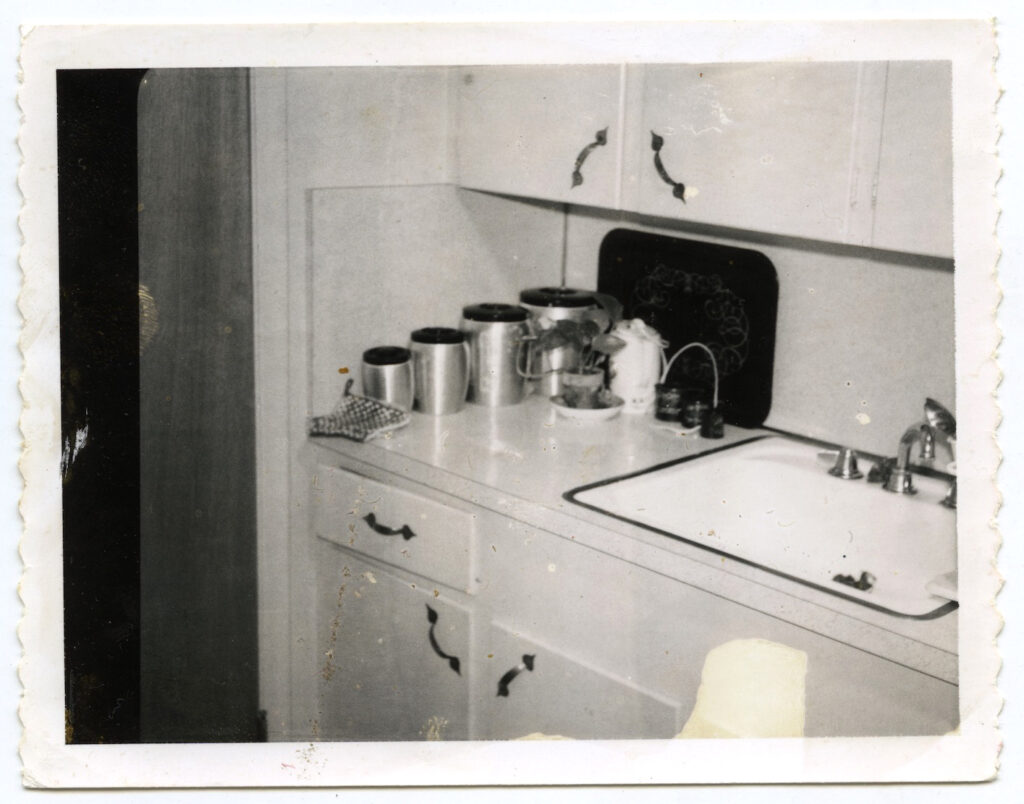

One autumn in my early twenties, I ventured with my father to the house where he was raised. As he cleared the yard, burned the garbage, and cared for the rottweiler who came from underneath the house, I roamed the land and the house. My father’s childhood home held the stories of my long-gone grandparents, all the aunties, the few uncles, and the dozens of cousins who all assembled before the years transformed them into the estranged side of my family. Though I knew that city living, northern living, would soothe the frenetic energy that lives in me, there was a place for silence and the stillness in that clapboard house and in the air that my ancestors once breathed.

A few years after my father passed, I visited my third cousin. She and I had met as young women at a family reunion. Because we Toomer girls shared the distance from our paternal families—she lived in Florida and I lived in New York—we formed a connection that felt like a friendship. When I swam in the waters of Duval County, Florida, I could have been floating in the Indian Ocean. With the heat of the sun warming my face, the crash of the waves meeting the massive shore, the crackle of the foam dissolving into the sand, and the glimmer of shells hiding in the tan granules, I was transported to the temporal sites of memory, and memory-making, my mind joining the ether.

Now, whenever I visit family in the South, many of whom have returned after enduring northern fantasies of productivity, I rejoice, in witness and savoring, at the pace at which many speak, and the sights, smells, and flavors of the South, not as an outsider but as an interlocutor (and one without the accent). I like to think I’m reconciling some of the time lost by my grandparents who moved hundreds of miles away from all that was familiar, to be safe, to remain, to continue, and to lunge forth into the future by way of having children. There is pride in that country life and honor in upholding a heritage that I was once taught to deny.

Jet Toomer is a writer and community organizer. A LAMBDA Literary Foundation Emerging Writing Literary Fellow, Toomer is cofounder of The Josie Club, a social club dedicated to celebrating queer Black women and femmes. She pens a newsletter on Substack called Tiny Violences. She has an MFA in creative writing and lives in New York.