Excerpts from Perrow’s essay in Southern Cultures, Vol. 19, No. 4: Winter 2013, appear below. Access the full essay via Project Muse or purchase the issue in our store.

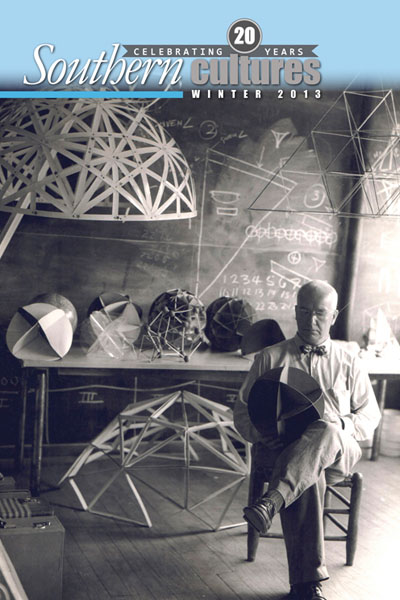

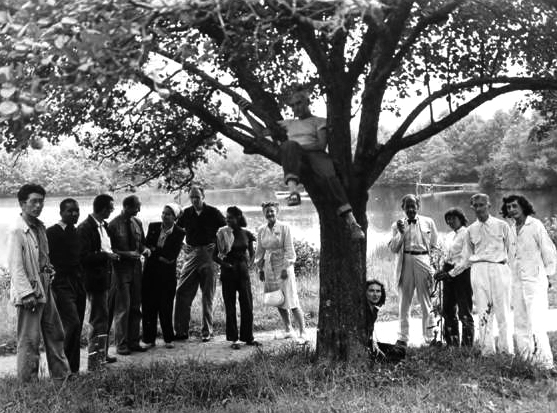

Black Mountain College, near Asheville, North Carolina, was an icon of progressive education during its short life, from 1933 to 1956. When I was there, from 1946 to 1948, there were sixty to eighty students and twenty faculty. There were few formal academic requirements, no required courses, no grades, limited resources, but an amazing abundance of creative students and faculty. Students in my two years included such notables as the writer Jose Yglesias, director Arthur Penn, painter Kenneth Noland, and sculptor Ruth Asawa. The Summer Art Institute in 1948 had John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, Richard Lippold. The regular faculty had as its star the abstract painter Josef Albers, and many notables in painting, mathematics, chemistry, weaving, and music, including Ilya Bolotowsky, Max Dehn, Natasha Goldowski, Anni Albers, Erwin Bodky, and Edward Lowinsky. The rest of the faculty included lesser-known but often distinguished writers, philosophers, musicians, historians, and a progressive psychologist.

The college was always a dynamic, explosive, self-destructive hothouse.

The college was always a dynamic, explosive, self-destructive hothouse. Since its inception, it had been a hotel for progressive ideas in American education, the arts, and the social sciences. Isolated in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, it was one of the very few schools in the country that was open to experimentation. A busload of new faculty and students arrived yearly, welcomed as refreshers and feared as competitors by those who had been there a year or two. Some tried to renovate BMC in their own image, some simply basked in its tolerance and idealism. The most authentic of the students and faculty were seeking to feed deeply on its vibrant flesh, immersing themselves in the unique experience and embracing its contradictions. All but a few moved on after a year or two, gratified or rejected, and a new busload arrived. A small core faculty stayed, providing some continuity and every three or four years wearily congratulating themselves on staving off another educational challenge and on disposing of the disruptive faculty and students who sought renovations (and sometimes achieved them). The core faculty sullenly cleaned up and tried again to square the circle, to create stability and security while proclaiming innovation. My busload, I believe, was quintessential.

Making Our Way

Almost everyone there at this period seemed a poster-child of some sort, representing a fragment of our culture—the closet gay, the civil rights activist, the communist, the avant-garde painter, the urgent truth-seeker, the parent-escaper. My poster was being about the only student from the West Coast (most were from the Northeast, particularly New York City); about being the only one without parents and siblings who had attended college (most students, but certainly not all, were from a well-educated upper middle class, or intellectual elite class); and being one of the few, I suppose, who had had little contact with Jewish people. BMC, in my retrospective judgment, was predominantly a Jewish culture. Tacoma, Washington, had a few Jews (including a friend), and some of my army friends were probably Jewish, but I never thought much of it. My acquaintance with Jewish culture was so limited that, even after I left BMC and went to live on the Lower East Side (East 6th and Avenue A), it struck me as very strange as I walked in my neighborhood (a Jewish enclave in 1948–49) that all the people chatting on the front steps spent their time telling Jewish jokes. I finally realized that BMC was the only context in which I had heard those wonderful jokes and theatrical accents.

Almost everyone there at this period seemed a poster-child of some sort, representing a fragment of our culture—the closet gay, the civil rights activist, the communist, the avant-garde painter, the urgent truth-seeker, the parent-escaper.

I was probably one of the few students who had no conscious intellectual pretensions; a C+ student in high school, I was slated for a career as an electrician, simply because I had to work when in high school and had a job with an electrical contractor. (I had two older brothers, and the oldest raised the two of us after I was nine.) I was glad to get out of Tacoma though, when I turned eighteen and was drafted into the army, so there must have been some itch to be other than an electrician in Tacoma. Three years as an infantry soldier did little for my intellectual development, but it did make me aware that I did not want to live the kind of life my fellow soldiers had lived. The life of a college student, financed by the G.I. Bill, looked much more attractive than returning to the electrician’s shop. Only in that sense did the army prepare me for college.

In high school I had written some poetry and wallowed in romantic classical music, read in an undirected, undisciplined way, and I continued this in the army. Free “G.I. Issue” paperbacks unaccountably included the novels of Thomas Wolfe, from North Carolina, and he spoke to my self-absorption. An older and quite sophisticated soldier took an interest, pressing me to read army paperbacks of Plato and Aristotle, which I couldn’t. I guess he was a communist of sorts, and talked grandly of a new society without injustice, and got into trouble with his superiors. The army’s current events reading material was slim and “safe,” so even communists might be reduced to reading the ubiquitous Reader’s Digest. He did, and an issue of the Reader’s Digest “changed my life,” as we are supposed to say. We had arrived in Japan, from combat duty in the Philippines, to occupy Nagoya. (The atomic bomb prevented my division, the 25th, from mounting a bloody invasion of Tokyo.) He saw a little story in the Digest about an experimental college that made it sound lovely: “Black Mountain is where you must go when you get discharged; take the G.I. Bill and run.”

Instead of running, I hitchhiked, in June of ’46, after one quarter at the University of Washington, where I was lonely and miserable and could only register as a home economics student since all other majors were filled. I had little money and few possessions, and hitchhiking was commonplace in those years. I didn’t enjoy it, and got roughed up by police and frightened by gay men. When I finally arrived about eight days later at the campus, to check it out and make an application, I must have been something of a sight (and smell). A small summer session, devoted mostly to the arts, was underway, featuring Jean Varda, Leo Amino, and Walter Gropius—none of whom were known to me. After cleaning up and getting some decent sleep, I wandered through art and music classes in a daze. Most of the summer students knew little about the regular program, but their enthusiasm was tremendous, and I tried my best to make a good impression during my interviews with faculty and administrators. I was told later that I was considered charming—a naive, unschooled veteran, who looked to be seventeen instead of twenty-one; who not only came from a place called Tacoma (where I struggled with Djuna Barnes and Rilke) but had half-walked from there to get to North Carolina. How I had come across Nightwood is a mystery to me now.

After three days at the college, I hitchhiked on to New England to find a summer job and waited eagerly to see if I was to be accepted. Of course, I was; I had the G.I. Bill, and the college was blooming because of their arrangement with the government. We got about $25 a month allowance from the Veterans Administration, and the college received payment for about half of the around $1,500 tuition and fees. There were many veterans among the eighty students, and the college loved us. Accepted, I hitched back in two or three days (one does not stop to sleep).

On the Cusp of the Cultural Revolution

Black Mountain was certainly a hologram of the nation’s pending concern with democratic governance, cultural innovations, and sexual freedom.

Waves of postwar American history seem now, nearly seventy years later, to have been concentrated in the two dynamic years I spent at Black Mountain College. With the end of the war and fascism, the college exaggerated America’s intensification of the democratic urge, the bursting of culture, and the sexual revolution. History is all retrospective judgments; no one can lay claim to any “true account,” and mine will be faulty, because my memory is not just poor, it is self-interested. But though my details may be selective, Black Mountain was certainly a hologram of the nation’s pending concern with democratic governance, cultural innovations, and sexual freedom. However distorted my account, it was a wild time, despairing and hilarious, and worth an interpretive reconstruction.

The intellectual postwar ferment roiled the college; the social issues were burning, and the arts were avant-garde, and there were not many academic hotels that would tolerate travelers with controversial baggage. We were the only college in the South that was integrated. Initially there were four African American students, but only one finished his first year. It was tough on them. Gas stations would not serve cars with Blacks and whites; Black students could not sit with white students in the bus to Asheville (and the whites could not sit in the back of the bus); any degree they received would be meaningless in the employment market. A Black student would do far better at a Black college. One “liberal” lawyer from Asheville resigned his position as the college counsel when the first Black student was admitted.

We had one defrocked communist teaching economics. As the Party apparently had, the faculty regretfully found him unbearable (as did I), and he was pushed out amidst much controversy and protest. We could not, as a liberal institution, be against the right of a communist to teach, and even proselytize, the students argued. The core faculty was certainly anti-communist, but they had hired him knowingly—the hotel should have at least one fellow traveler—so I do not think his politics were the main issue. Instead, I feel that he did not want to feed off of the experience; he wanted to convert it and establish a base for communism in higher education. Those who wanted to capture, rather than embrace and be suckled by, the community always had to leave. I had roomed with one of the three or four students he brought with him, and finally asked him what this “historical materialism,” of which they talked incessantly, was all about. He gravely gave me two books to read, both of them weighty. I did not get beyond the titles. The 18th Brumaire, indeed! What was it? If the theory could not be summarized in five minutes, I would have none of it.

We made a distressing, unnerving attempt at registering the Black vote, an effort that was almost instantly abandoned when the core faculty became worried and the surrounding community outraged.

We took our support for Henry Wallace’s presidential candidacy into bucolic, benighted Buncombe County, but instantly retreated under fire. An attempt to support a strike at a Lucky Strike plant fizzled. We made a distressing, unnerving attempt at registering the Black vote, an effort that was almost instantly abandoned when the core faculty became worried and the surrounding community outraged.

Making the Community Work

The split in 1948 that led to nearly half the students and half the faculty departing prefigured the nation’s culture wars. One side, I will label them the “conservatives,” wanted the plastic and performing arts to rule, and social sciences and philosophy to be reduced or abandoned. (The social sciences and even history were “anti-life,” declared the most powerful figure in the community, Josef Albers.) They wanted to cut student scholarships, pay faculty according to the traditional ranking system and length of service rather than family size, end the work program, and spend money on painting fences. The other side, the “liberals,” wanted to keep the social sciences and philosophy, retain need-based scholarships and the work program, buy another piano, and keep family size as a basis of faculty salaries. The refugees were overwhelmingly on the first side, so the overtones were national (Germany versus America, or, from the conservatives’ perspective, European standards versus American indulgences) and nasty (fascists versus democrats, or, as the conservatives put it, democrats versus communists). The former won, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. With half the students and faculty gone, most in protest, there were few new students (because of no scholarships, and declining veteran enrollment, I suppose) to replace them. The head of the winners, Josef Albers, left for Yale two years later and the other power, Theodore Dreier, was forced out. The poet Charles Olson returned to the college as Rector in 1953 and held on as best as he could with his exuberant, extravagant, and bulky character. Literature (the “Black Mountain Poets”) won out over painting and weaving, until all crumbled and quietly passed away in 1956.

Progressive colleges always have an intensified governance problem: how shall they be run? At BMC no foundation owned the place, the faculty did. There was no rich and interested Board of Trustees watching benignly from afar. There was only the faculty and a student representative. The ideology was participative and democratic, and this attracted young faculty and idealistic students. But it was essentially run by the core faculty from the 1930s and early 1940s, “old men” like Theodore Dreier and Josef Albers. They forced the resignation of the visionary founder, John Rice; the feisty, disrespectful Eric Bentley; a student wrongfully charged with prostitution (she was hitchhiking) and grievously mistreated by the State Police (she “embarrassed” the college); and a gay faculty member, the Rector at the time, whose behavior was beyond reproach on campus but who was arrested (set up, some said) in Asheville. (The rulers could be cruel, and often were. Dreier arranged to have the charges dropped, but the Rector was told to return to the campus after midnight and be gone forever by breakfast. No further contact was made with him, and he drifted to California, reinventing himself as a postman, according to rumor, and disappeared.)

Another conflict was between the official ideology, which held that community was to be the focus, versus the operating spirit of libertarianism.

Another conflict was between the official ideology, which held that community was to be the focus, versus the operating spirit of libertarianism—making each flower bloom bigger and brighter than any others, as Eric Bentley jeeringly referred to it. Making matters worse, some blooms were big and bright. The creativity of the members was large and cherished, but the egos were larger still. Living in a crowded cocoon cloistered in the Bible Belt, preaching community ideals with a faint whiff of communism, with out-sized faculty and student egos, one may be surprised the college lasted as long as it did. Only the incessant comings and goings of the travelers renewed it.

One issue that highlighted the dilemma of the participative governance of strong wills was the plight of refugees in the torn skein of Europe. Half of the faculty were refugees from Europe (Germany primarily, but also Russia), and the war-torn continent was at the forefront of many dining hall discussions. It precipitated our own war, dubbed the “mush war.” Significantly, it was not a refugee who finally put the topic of the plight of European refugees on the community agenda but one of the farmers, a dour, hardworking man. (He was one of the few who refused to be interviewed by Martin Duberman for his excellent book, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, on which I draw occasionally for this account.) He felt that the community was too isolated from the rest of the world, and it should get involved and send regular CARE packages to refugee organizations in Europe. One could hardly be against this, especially considering the many refugees on the faculty. But the students themselves did not have much money (although some were from wealthy families), the faculty was barely paid, and the college itself seemed always in threatening debt.

Was our self-indulgent individualism compatible with community responsibilities?

The farmer proposed at the weekly community meeting that we needed to sacrifice, give up something, to match the sufferings of the refugees in Europe. He proposed, as an example, that people should give up cigarettes for one day a week and send the money to CARE, only to catch himself in confusion, realizing that he didn’t smoke. Recovering, he announced, “I will give up milk.” The issue was discussed for a couple of weeks, with guilt running high; indeed, it was a guilt-edged issue tailor-made for us. Was our self-indulgent individualism compatible with community responsibilities? We thought so, and ended up voting to eat only mush for three meals one day a week, and send the savings to Europe.

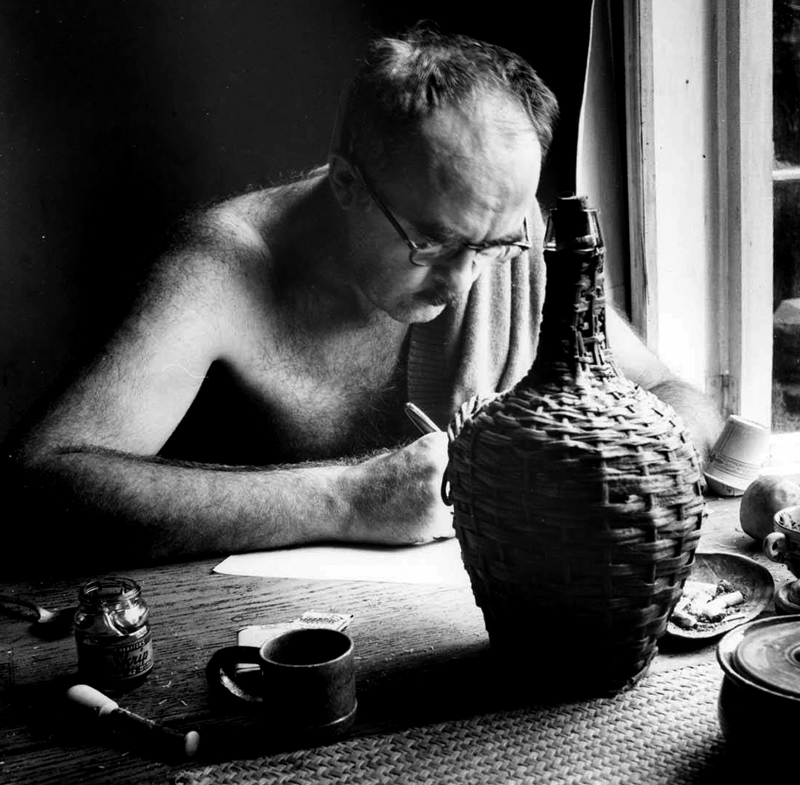

Opposition was probably substantial, despite the vote, but it could not be overt. We had to sign a pledge, and initially, only a small minority refused. A significant refusal was my favorite professor, Albert William “Bill” Levi, a philosopher from the University of Chicago. He announced that he and his wife, Mary Caroline “M. C.” Richards (a lovely writer), were already sending regular donations. (“How can we tell?” asked the mushers. “Have we seen receipts?”) On Wednesday the anti-mushers were asked to eat their breakfast, lunch, and dinner at separate tables, where there would be the appropriate condiments and settings. They marched from the cafeteria line to their tables in a corner, belligerent and perhaps a bit ashamed. Some elderly members of the families of refugee faculty were clearly bewildered, and were non-mushers. At the mush tables we made self-satisfied arguments about joining in the sorrows of the rest of the world rather than wallowing in our own self-indulgent introspection. Why were the refugee faculty not in front in the mush war? we asked. The sacrifice was all for the likes of them. But was the sacrifice even genuine? Some wanted the little community store, with cheese and crackers and candy bars, closed on Wednesday so people could not surreptitiously stock up; even close it from Tuesday afternoon until Thursday. Was it legitimate to buy your way out and not go hungry, or did you have to suffer? (Suffer, was the consensus.) The number of non-mushers grew, from perhaps 10 percent to 30 percent. Non-mushers organized a CARE package program and claimed they did more than the mushers and, moreover, it was truly voluntary. Mushers, they said, were intimidated; it was not really as voluntary as sending money to CARE but an instance of “fascist” pressure. (Anything evil in 1946 was marked as fascistic; we had just fought a war against this scourge. A decade later, communism would serve as the nation’s evil totem.)

Providentially, the kitchen staff and the business manager gave the community a way out. The business manager said that little was being saved. We had a farm that supplied much of our meat and vegetables (working on it was one of the options of the compulsory work program for all community members). The two cooks complained about the uncertainty of how many non- mushers would show up; it made meal planning difficult. Not so privately they thought it absurd to eat mush all day. (They were much admired and respected, as cooks tend to be in total communities. The head cook Mallory was uncommonly tolerant of the sexual activity of the students—she knew who showed up with whom at breakfast—and if Central Casting got a call for a beloved Black cook, she would be the first pick.) Another stormy community meeting was held. The program received an ignominious vote of no confidence, and the community sustained another wound.

Along with the wounds, the meetings were many. There was little for this isolated community of about 120 souls to do in the evening. Asheville had the closest movie house and was far away, and even visiting the one roadhouse within 10 miles was difficult since few people had cars. The alternative to hanging out in a crowded, dingy dormitory, where most students lived, was either your private study or a meeting in the community dining hall. At such meetings you would learn that people did not put in the required three or so hours of voluntary labor on the farm, the kitchen, the business office, or work programs that cleaned up the grounds, or fixed shutters and leaky roofs. The work program was chaotic and some simply refused to contribute. An ambitious effort to organize it by a faculty member, John Wallen, and his students was met with the charge of “taking over the community.”

Access the full essay via Project Muse or purchase the issue in our store.

Charles Perrow is the author of several books in the areas of organizational theory and disasters, including Complex Organizations, a Critical Essay; Normal Accidents; and The Next Catastrophe. He has had teaching appointments at Yale, Stony Brook, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pittsburgh, the London Business School, and the Imperial College, London.