Emmet Gowin, “Here on Earth Now: Notes from the Field,” Pace/MacGill Gallery, September 28, 2017–January 27, 2018.

Before cable television, video games, Netflix, and smartphones, insects filled the summers of southern childhoods. Remembering the pain of past stings, kids learned to watch for wasps’ nests in the poles of swing sets and chain link fences. At twilight in suburban yards, country fields, and city parks, children caught lightning bugs and slapped mosquitoes. In the dark, young people studied the moths circling porch lights, street lamps, and camping lanterns. Even in those years when girls and boys ran and rode their bikes through the sprayed fog of the DDT trucks, some bugs survived for them to look at, track, and capture. In the moist, hot air of summer, both the kids and the bugs ran free.

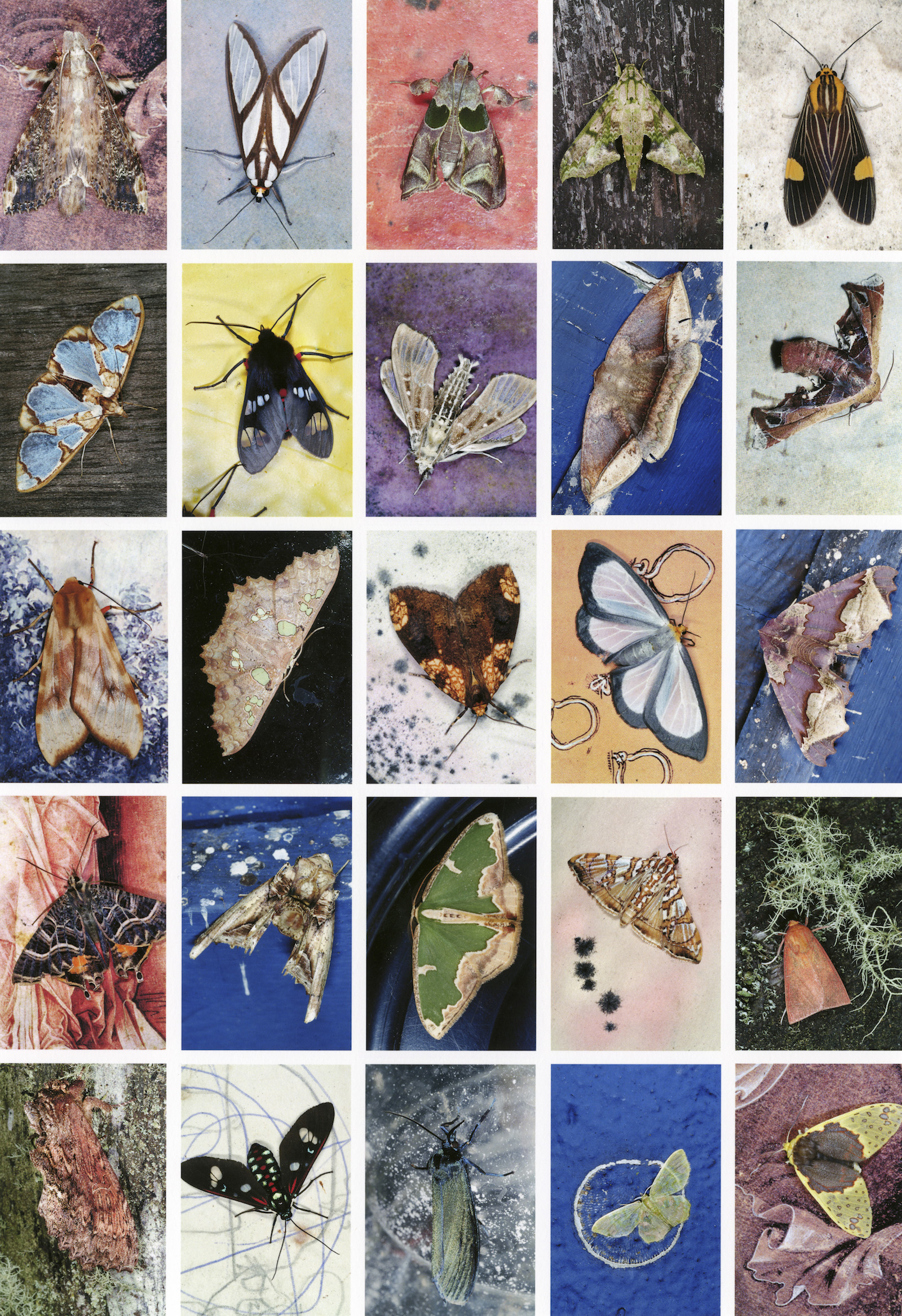

Though Danville-born photographer Emmet Gowin is seventy-five, following him as he moved between the moths on display in his current exhibition “Here on Earth Now: Notes from the Field” at Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York, I felt like I was down in the dirt with my best friend again, tracing the trails of beetles. Gowin presents his “mariposas nocturnas,” night butterflies in Spanish, in photographic prints which are composites of twenty-five “portraits” of individual specimens of different species arranged in five by five grids. These moth grids make up about a third of the exhibition at Pace/MacGill, framed by other photographs of the forests in which he discovered them, the traces moths and other insects in these places leave behind, and his wife Edith Gowin, alone or with him or surrounded by insects. Gowin has also published a book Mariposas Nocturnas: Moths of Central and South America, A Study in Beauty and Diversity, recently released by Princeton University Press. Together, the exhibition and the book bring his work full circle and offer a radically different expression of one of his favorite subjects, our capacity to see the beauty and transcendence on offer in the world.

Gowin traces his interest in insects to a boyhood spent tromping around woods and fields in Virginia. As a boy scout, he caught and kept small animals like frogs and worked on wildlife and wilderness badges. He realized early in his life, “Nature was where I was the happiest,” “where I felt like I was on the edge and learning.” He also collected stamps, a hobby that taught him the value of tiny variations and distinctions between nearly identical objects and exposed him to the thrill of finding rare specimens. Later, as a father of sons, he led a scouting troop for a year and worked hard to teach his charges to preserve and pin insect specimens decently and to do the work of scientific identification. In his earliest Danville photographs, his subject is often the wonder of childhood—niece Nancy with her dolls, nephew Dwayne and his friend Barry with two turkeys, Nancy and Dwayne rolling around in the recently cut grass. In his new body of work about moths, Gowin takes a different angle, revealing his own still surviving awe before the beauty of the natural world.

Gowin traces his interest in insects to a boyhood spent tromping around woods and fields in Virginia.

At Pace/MacGill as he shows me around his current exhibition, Gowin deploys species names and other terms scientists use to classify moths like a spell, as a language for creating magic rather than order. Surveying the grids, he delights in the serendipity that enabled him to photograph extremely rare species. He marvels at types of moths that ward off potential predators by mimicking the look of stinging insects. And he describes the painstaking act of sequencing the grids of individual moths found at particular locations by paying careful attention to the rhythms of their colors and shapes. Photographing the tiny living beings, he explains, was as great a challenge as making photographs of landscapes by shooting out of airplanes, his previous body of work that includes a series of shots of the Nevada Test Site. At first, after using a mercury vapor lamp and black light to draw the insects, he photographed the moths wherever they landed, on a plastic sheet or the side of a building or the headlight of a truck. Looking at prints made against the blue-green wall of a science field station sometimes weathered and other times repainted between his repeated visits, he discovered how the color of the background against which he photographed the living moths shaped the resulting images. After he shot a moth that landed on a William Blake image he brought with him into the jungle, he began traveling with scans of work by Blake, Degas, Matisse, and other artists. In some grids, tiny fragments of paintings are visible behind the moths.

It was the scientists, however, who helped Gowin figure out how to transform his new interest in Central and South American moths into art. He had photographed insects before. In 1976, he dusted a nineteenth century book of rhetoric almost eaten away by insects long gone with the bodies of dead bugs his kids had collected off the windowsill of an old barn. Though he loved the eight by ten color negative he made, for years the image existed all by itself, without “any brothers and sisters.” Gowin began making his moth photographs on a visit to Ecuador that offered him a respite from his work photographing the traces left behind on the landscape by nuclear bomb tests, but he made multiple trips to Central and South America before he discovered how to turn his interest into a body of art. After he convinced the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama to accept him as a visiting scholar, a resident scientist there asked him to make a poster to explain to other researchers what an artist was doing at their field station. Adopting a form scientists have used to explain their work visually, he arranged images of twenty-five individual moths into a five by five grid and hung a poster of the composite in the entryway of the main building.

On the walls of the gallery, the moth grids operate in a place where art’s wonder and beauty and science’s order and knowledge meet, a territory explored in radically different ways by artists including Hilla and Bernd Becher and Mark Dion. Gowin has said in interviews that the grids remind him of yearbook photos, alternate sets of “portraits” of earth’s children. They suggest a kind of index, a typology, a visual survey of the moth species present in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, French Guiana, and Panama in the early twenty-first century. Yet they also provide a way of seeing how one type of insect in one part of the world generates an extravagant variety of beautiful forms. Employing a radically different aesthetic, the moth grids produce a version of awe before nature more often associated with large scale mountain vistas of landscape painting and photography than with intimate views of the insect world.

Across more than half a century, Gowin has filled his work with circles as forms and as metaphors for how repetition and the act of return order the passage of time. Working in the seventies with a circular lens too small for his camera, Gowin made prints in which the blacked-out edges of the rectangular negatives framed round images at the centers. In his Danville photographs, sometimes made with that circular lens, seasons and holiday visits and aging family members moving through the cycle of life come around again and again. Later aerial work includes photographs of crop circles created by pivot irrigation and round bomb craters blasted into the desert. Opposite in scale, the moth images include multiple circles, the faked eyes that appear in subtly different forms on many wings. Though Gowin only includes adult specimens here, moths like butterflies embody the cycle of life as caterpillars become pupae and then flying adults.

Employing a radically different aesthetic, the moth grids produce a version of awe before nature more often associated with large scale mountain vistas of landscape painting and photography than with intimate views of the insect world.

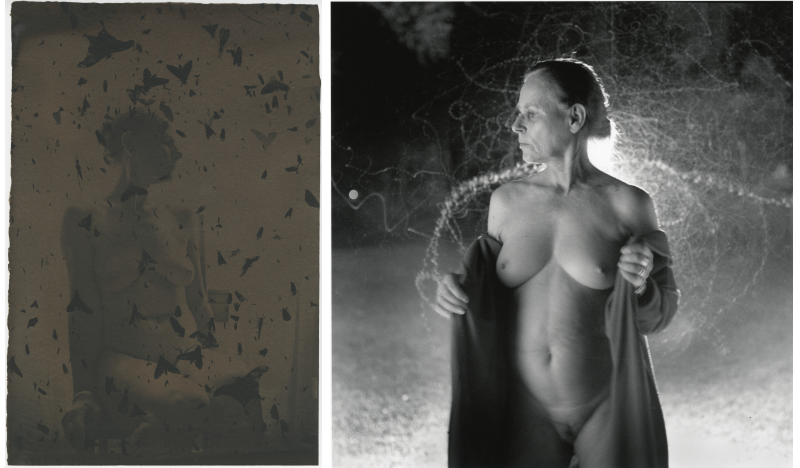

In “Here on Earth Now,” two photographs of insect tracks in a layer of mist on a collecting sheet, two salt prints of a Bolivian rain forest, and a five by five grid of the stains of excreted toxins left behind by insects on the collecting sheet form an intermediary set of images between the moth grids and the more experimental work that makes up the rest of the show. Gowin brings the playfulness of kids running around in the dark to the multiplying images on display here of the subject he has circled around his entire career, Edith Gowin. In the jungle making moth images without her, Gowin cut her likeness out of an photograph and used it to shield his eyes from the light used to draw specimens. Once, out working with “Edith” propped nearby on a railing, he looked up from the dark, saw her shadow backlit by the light, and thought for a second that she was present. This experience inspired him to make a series of images he has called elsewhere “Edith in Panama” in which Edith appears alone or in company with herself and with Emmet, both in photographs and as silhouettes made by cutting images out of earlier photographs. In some of these works, Gowin has altered and collaged negatives, combining them or printing one on top of the other. The resulting layers originate from and in turn represent the passage of time. “For William Blake,” presents multiple silhouettes of Emmet and Edith, sometimes in intimate embrace, in an almost grid. Gowin explained that he made this picture by arranging silhouettes made from other photographs on a canvas, tracing the images, painting the traced shapes black, and photographing the painting. Amid this experimentation, a salt print made by simply shooting Edith in a window, a pose returned to repeatedly across Gowin’s body of work, presents the layers of time in an alternate way, as a gorgeous play of shadows and light kissing the curves and creases of her aging body. Connected to the moth grids through other photographs on display here which present her almost naked surrounded by bugs or backlit by the insect light or veiled by raindrops trapped in a spider’s web, “Edith, 2005” makes us see that history, whether etched by life on a lover’s body or by evolution on a moth’s wing, is beautiful.

This essay is part of our Shutter series on southern photography.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is the Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and the author of Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (Vintage, 1999), A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle-Class fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (Oxford University Press, 2011), and Cool Town: Athens, Georgia and the Promise of Alternative Culture in Reagan’s America (forthcoming in 2017).

Emmet Gowin (b. 1941, Danville, VA) received a BFA in Graphic Design from the Richmond Professional Institute (now Virginia Commonwealth University) in 1965 and an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1967. Gowin’s work can be found in museum collections worldwide, including the Art Institute of Chicago; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Tokyo Museum of Art; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.