"If you studied objects, you’d begin to see that they have much to teach—not only about beauty and utility, ephemerality and permanence, but also about history, about people."

For almost thirty years, my parents ran an antique shop in an old two-story house in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. When I was little, stuff arrived and departed by way of my mother’s van, a matte-green 1970s camper, stripped of its bunk and golden burlap curtains. It had no air conditioning and smelled of cigarettes and french fries. Daddy kept the shop while Mom went out on buying trips or traveled to set up her booth at antiques shows in Raleigh or Charlotte or Asheville. This arrangement suited them, as he was sedentary and depended on routine, and she liked to be out and about.

She enrolled first my brother, then me, in a morning preschool at the Episcopal church down the street, but we spent our afternoons at the shop. While Daddy, upstairs in the office, read the Wall Street Journal or wrote sales in his ledger, and Mom talked to customers on the telephone or researched her latest find, my brother and I squabbled in the downstairs playroom, which smelled of the products our mother used to brighten her wares: Wright’s silver polish, baby oil to clean lacquer, Old English to fill in scratches on furniture. Penned in by a baby gate, we played amid the toys and books strewn all over the floor, the radio playing the hits: “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” and “Funkytown,” and “Sexual Healing.”

For lunch, we ate peanut butter or bologna sandwiches and drank Coca-Cola out of Bugs Bunny glasses that had come free or cheap with a meal at a drive-thru. Sometimes customers would look all around the shop, unimpressed until my mother offered them a Coke in a glass with Superman or Yosemite Sam on it.

“Oh, we’re collecting these, and this is the only one of the four we don’t have,” a customer might say, and Mom would reply, Just go on and take it, privately disgusted that a mass-produced glass with a cartoon character on it had been the only thing in the whole shop to incite any interest. Ignorance of antiques she could pardon, even welcome, since it gave her an opportunity to teach, but lack of interest was unforgiveable. Her own curiosity was so powerful that she just couldn’t fathom people who showed no desire to know things.

That curiosity was what she and my father shared, and they both loved to tell what they knew. Spend more than a second looking at a particular object, and they’d start talking about it. They would explain what cultural developments in China or Japan, England or Germany had led to its being made at a particular time. They would hypothesize about how it had come to North Carolina and what sort of people might have owned it. They would show you how to tell the difference between cast glass, which has a seam, and blown glass, which has a rough place on the bottom where the pontil was broken off. They would show you how an object came apart, how it was used, how it was made. One of my mother’s favorite moves was to announce that it was time to perform a “full rectal” on a table or chair. She’d then ask the stunned customer to help her flip the piece over so that together they could study the joinery and look for secondary woods, cabinetmakers’ marks, or evidence of repairs.

Her own curiosity was so powerful that she just couldn’t fathom people who showed no desire to know things.

My brother and I watched these interactions with customers and learned to imitate them. We were given to understand that developing a knowledge of antiques went far beyond familiarizing yourself with current tastes and the momentary caprices of the market. Your eye had to be trained to appreciate differences in craftsmanship and proportion, and you needed to acquire sufficient understanding of the history of material culture to know what those differences could tell you about an object’s provenance. If you studied objects, you’d begin to see that they have much to teach—not only about beauty and utility, ephemerality and permanence, but also about history, about people.

If you studied objects, you’d begin to see that they have much to teach—not only about beauty and utility, ephemerality and permanence, but also about history, about people.

My favorite items in the shop were those that had to do with daily living. I liked holding in my hand things people had used in an intimate way two hundred years before: a silver snuffbox once carried in a man’s pocket, a wooden busk a fashionable woman had inserted in the bodice of her dress to stiffen it, the tongs they’d heated in a fire and used to curl their hair. Through these things I learned that people from the past were not made up, like characters in books, but had been real people with actual physical bodies.

For a while, we had at the shop a square cabinet, about chest high, made of a pretty, dark wood like mahogany or cherry. On the top, two panels folded out to the sides, revealing a round hole where a ceramic washbasin could fit. There were also holes in which to set a drinking glass, shaving mug, and toothbrush tray. At the back of the cabinet was a brass ring that you pulled to raise a mirror, which locked into place with a satisfying click. Below this, behind two doors, was a space for keeping your pitcher and other necessities, and beneath that was what looked like a drawer. When you opened it, the front legs of the cabinet came along, and the pot was revealed. I delighted in demonstrating how everything worked, always saving the revelation of the pot for last—the punchline: It’s a toilet!

I loved anything with a hidden compartment. I loved the words for things now obsolete: porringer, Betty lamp, sugar nippers, niddy noddy.

I liked the sewing tables, with their hinged tops and room inside for your needles, scissors, thread, and wool. I remember one, especially, a dainty, painted number on pointy feet; it had for storage a silk bag that hung below the table apron like an udder. I also liked toiletry cases, with their partitions for glass bottles and their neat silver or bone tools for grooming. Best of all, I thought, were the boxes that opened to make a slanted surface for writing. That surface might still be covered with its original green or black felt, and there might remain the frayed stub of ribbon that you pulled on to lift the writing surface and access the compartment beneath, divided into sections to hold ink, pens, penknives, seals, wax, and paper. These traveling desks could be plain or quite elegant, with dovetail joints, decorative inlay, and if we were lucky, a key that still turned.

* * *

As enamored as I was of things in the shop, I knew they were not really ours. They might stay for years, or they might be sold tomorrow. They were like the animals a farmer raises for slaughter—best not to get too attached.

I also knew how important all that stuff in the shop was to our parents and could not help feeling a little jealous of it. Once, a customer asked my mother if it didn’t make her nervous to have us little children around all these precious antiques. As soon as Mom proudly told the woman that we had never broken anything, my brother picked up a porcelain teacup and dropped it on the floor. He looked me dead in the eye when he did it, she would always say later. He knew exactly what he was doing.

Once, I put my foot through the cane seat of a chair and got a spanking. Why did you do it? When we told you not to? They would always ask these questions when I’d done wrong, and I could never come up with a good answer. To see what would happen? Because I felt like it? Because . . . the devil made me do it?

* * *

As soon as toddlers cotton on to the idea of ownership, they begin clutching at everything in sight and repeating one word until it sounds like a mantra: mine, mine. Who can blame them? When we are children, we live in a world not built to our scale, and we naturally want to find things to call our own. Our first possessions delight us because they are intended for us, unlike so much else in the house, all the forbidding and forbidden stuff we are told to leave alone because it is fragile, expensive, dangerous, or simply not ours.

The first toy I remember is my shape sorter—a wooden box with a red, hinged lid. In the lid were holes through which to pass square, triangle, circle, rhombus. After a few frustrated attempts to line up the blocks with the holes, it occurred to me to simply open the lid and drop the blocks inside. Problem solved. Toy conquered.

My crib. At bedtime, my mother put me in it along with everything I owned. With the light on, I’d play happily, throwing toys out one by one as I tired of them, until the crib was empty, and I’d finally go to sleep.

A plastic diaper pail. In the top was an ineffective deodorizing tablet that looked like a giant Sweet Tart trapped behind a grill—perhaps the reason I have never cared for Sweet Tarts.

Teddy bear—classic brown, stubby arms and legs, plastic eyes reflecting the light—unimaginatively named Teddy.

Fisher-Price record player, red and white, with a compartment in the back for storing a handful of plastic records. I’d fall asleep to “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” as the humidifier purred and bubbled, pumping into the room a cool mist meant to appease my asthma.

My soft doll with comedian Flip Wilson on one side and his alter-ego Geraldine on the other. When you pulled the cord, Flip/Geraldine said things like they said on TV: “Oh yeah? And I’ll punch you right in the fist with my face!” and “The devil made me buy this dress!”

My coat tree that tipped over when you tried to hang a coat on it.

My brick-red chair with JULIA painted across the back in yellow letters.

My nineteenth-century pine rope bed.

A Victorian child’s rocking chair with a finely caned seat that I was afraid to sit in.

* * *

The Proustian madeleine: it is symbol, it is synecdoche, it is smell, it is taste, it is memory, it is thing. It is the hardest-working cookie in all of literature. What might mine be? A Little Debbie Nutty Bar, perhaps, the overly sweet taste of which would summon my grandmother’s kitchen, where her dark green cookie jar, shaped like an apple, sat on the counter next to one of her three televisions. There in her kitchen we watched people spin the glittering wheel on The Price is Right while we ate at the round table with its own spinning wheel—the Lazy Susan that smoothly delivered napkins, salt and pepper, more supper.

I have not eaten a Nutty Bar in years, but whenever I go to the grocery store and see the yellow box, the red letters, and Little Debbie’s smiling cheeks, I can see that kitchen again, hear the wheel spin, and feel the sugar charging through my jaw. It makes my teeth sing, my brother would say. One look at that cookie, and, à la Proust, I am transported.

Yet, there’s no one food that I would single out as being above all others in its ability to trigger memories of my childhood, that time before the trouble of growing up and being a grown-up. Little Debbies and fried chicken and Raisin Bran remind me of one grandmother’s house; sweet potato pie, orange marmalade, and stewed tomatoes conjure the other’s. It happens with songs, too. When I hear Harry Connick Jr.’s version of “It Had to Be You,” I’m at my wedding reception, dancing with my father, and when I hear “Nessun Dorma,” I’m in a close, dimly lit room at the crematorium where he is laid out in a box.

Of the thousands of objects I grew up knowing and own now, which is my madeleine? I cannot choose.

And what about objects? Of the thousands of objects I grew up knowing and own now, which is my madeleine? I cannot choose. At home, in the office where I write, a Jane Austen action figure and a Lego Shakespeare are jokey reminders of my vocation. A prize ribbon that says “Nap Champ” came from a party I attended twenty years ago when I was a graduate student; a mug holding pencils was given to me by a friend now dead. All of these things mean something to me—each is a key that unlocks a memory or set of memories. No one of them is essential, but together they fill a cabinet of recollection that I would hate to lose.

Mom was always moving stuff from place to place, all the while bemoaning that there was too much of it. “Stuff!” she’d say, and shake her head as though the idea disgusted her. And then, the next day, the next hour, she’d bring home another thing from a flea market or junk shop, pleased with herself for having paid much less than what she knew she could sell it for. From her, I learned early on that knowledge, aside from its nobler qualities, can give you a financial advantage. But for my mother, the business was about much more than profit.

In The Iron Tracks, a novel by the Israeli writer Aharon Appelfeld, the main character deals in Jewish artifacts such as “wine goblets, candlesticks, menorahs, and even an old prayer book.” He says, “This is my strange way of making a living. I buy antiques whose value no one here can estimate, and I sell them to collectors . . . No pleasure is like that of discovering an antique.” Later, another character tells him, “Your work is holy. You mustn’t leave these precious objects in the hands of strangers. Marvelous memories are stored up in them.”

How could she stop bringing things home when the world kept turning up its treasures to her?

My mother was not religious, yet she saw relics everywhere. She often said of a thing she brought home that she’d felt compelled to “rescue” it from its abject surroundings, from the shop proprietor and the other customers too ignorant to see its value. She couldn’t just leave it sitting there—it was too good. How could she stop bringing things home when the world kept turning up its treasures to her?

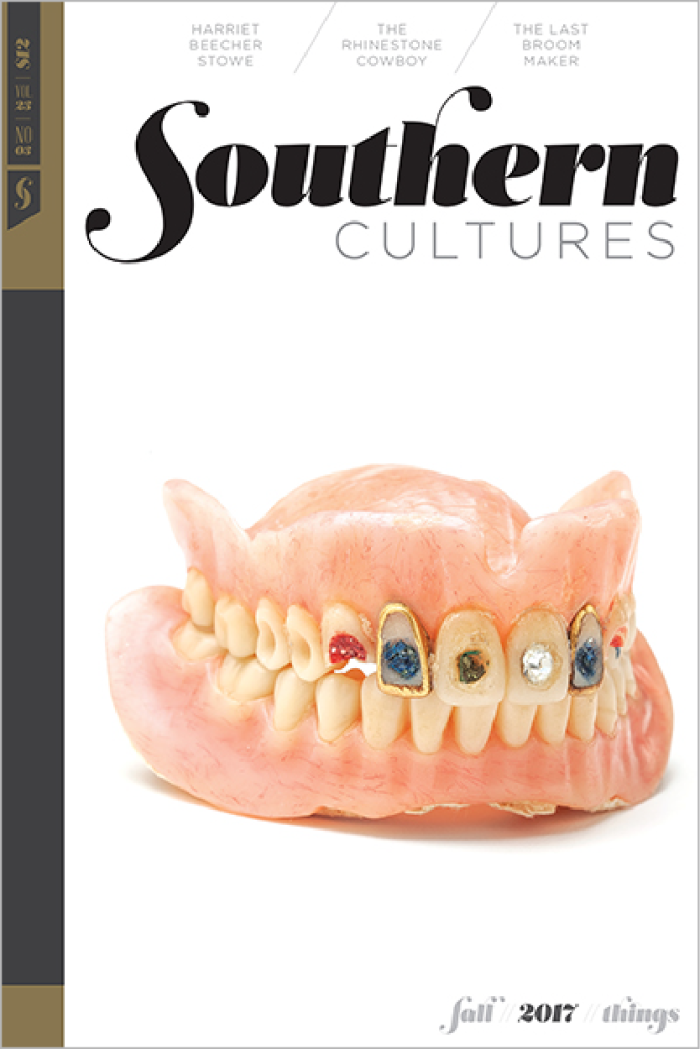

This essay first appeared in the Things issue (vol. 23, no. 3: Fall 2017).

Julia Ridley Smith’s fiction has appeared in American Literary Review, Arts and Letters, the Carolina Quarterly, Chelsea, The Greensboro Review, storySouth, and elsewhere, and is forthcoming in the Alaska Quarterly Review. An editor at Bull City Press and Inch Magazine, she currently teaches creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.