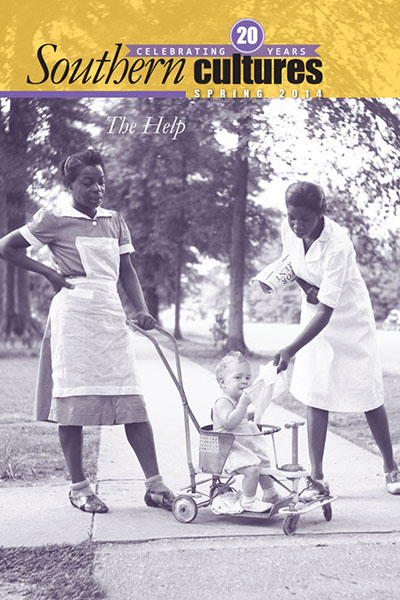

“Lauded for her endless gifts and selfless generosity, Mammy is summoned from the kitchen to refute the critics of southern race relations; cruelly circumscribed and taken for granted, she silently confirms them all.”

“Mammy” is one of the most vivid characters on the southern cultural landscape. Immortalized in songs, stories, and films, Mammy is the endlessly loving, eternally loyal black woman who nurses, scolds, comforts, and guides her white charges from the cradle to adulthood and beyond, dependable in every emergency from colic to a failed romance. In one famous incarnation, she is Scarlett O’Hara’s indispensable emotional anchor; in another, she is William Faulkner’s Dilsey, whose steadfast moral plumb line marks the Compson family’s inexorable decline. Ageless, sexless, and undistracted by her own children, she pours endless love on her white babies, teaches them (and their mothers) everything important from manners to biscuit-making, and upholds family standards even when her white folks are tempted to crumple. “She’s like a member of the family,” they assure all comers, echoing the planters’ faded evocation of “our family, black and white.” Lauded for her endless gifts and selfless generosity, she is summoned from the kitchen to refute the critics of southern race relations; cruelly circumscribed and taken for granted, she silently confirms them all. In an age of unstable families and revolutionized race relations, it’s no wonder that Mammy is controversial.