Georgia’s coastline is roughly a hundred miles long, pegged at the north by the Savannah River and to the south by the St. Mary’s. A series of barrier and coastal islands marks its length and protects an essential and pristine estuary from Atlantic waves. Between mainland bluffs and barrier islands is a salt marsh, the second largest in the United States, a maze where rivers and creeks skirt islets of mud and sand.

Oysters thrive in such an estuary. These bivalve mollusks are ugly creatures. They grow in clusters and have razor-sharp edges. They stretch heavenward like spires on a devilish cathedral. They’re as wild as their habitat. Restaurants rarely sell such unruly oysters. Riverside roasts, where oysters are steamed over fire, then shucked gleefully by eaters gathered around newspaper-covered tables, are their more common milieu.

In the early 1900s, decades before the rise of the half-shell craze at urban raw bars, Georgia dominated the oyster industry in the United States. Back then, consumers ate tinned oysters by the ton. Canneries where freshly-harvested oysters were shucked and steam-sealed into aluminum, and the low-slung sloops that dragged oysters from marsh to shore, provided hundreds of jobs in coastal communities. After World War II, industry growth ebbed. By the 1980s, oystering in Georgia had all but stopped as consumer tastes changed, Asian competition muscled in, and a cheap workforce jumped skiff for dependable wages in city trades. Only a handful of dedicated oystermen and their faithful but few customers endured.

The rise of aquaculture—scientific shellfish farming—has revived long dormant oyster fisheries in Virginia, Alabama, the Northeast, and the West Coast in the last twenty years. But, until very recently, innovation had left Georgia behind. Change is coming slowly to this state.

A clump of oysters, seen here in early evening at low tide, can be plucked from the mud like a bouquet of flowers. Oysters often aggregate along riverside borders of Spartina, which covers marshlands like a crew cut. One cluster may contain a dozen or more oysters, but after culling only three or four edible oysters will remain.

Seven-foot tides drain Georgia’s marshes twice a day. Wild oysters live subtidally, meaning only low tide exposes the mounds to fresh air and human access. Prime oystering grounds can often be found atop mud dunes that run along the banks of wide tidal rivers or hidden up creeks that snake through beds of marsh grass. A diet of phytoplankton and big gulps of brackish water give wild oysters a salty, grassy taste. At low tide, stepping on oysters provides the only route to navigate river bottoms on foot. Pluff mud, a sulfur-scented goop, can engulf a human leg easily up the knee, making mobility difficult.

An oystering expedition must leave dock before low tide and arrive at the destination while water channels remain navigable. Boat captains will either ram their small ships onto a steadily-surfacing oyster bed, or drop anchor and wait for the water to recede out from under the hull. The vessel is then stranded until the tide returns. Watermen spend these hours of intermission busting apart clusters of oysters into manageable clumps or shuckable single shells. Often, metal rods, screwdrivers, or steel tools break down clusters best. To work oysters in rising waters requires wading, at best, waist deep in an opaque river and slogging through mud in soaked boots and pants, dragging sloops or skiffs in tandem.

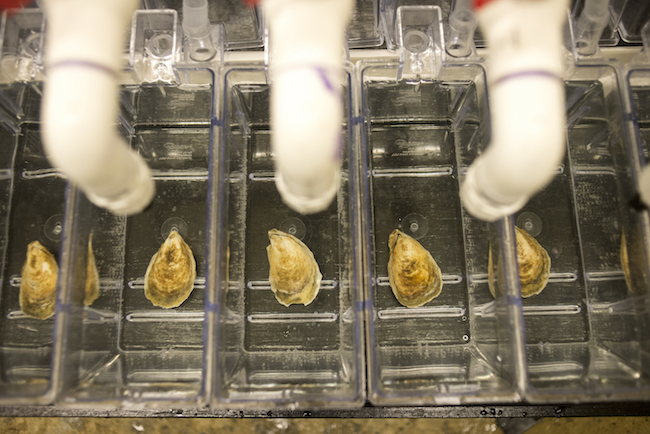

Traditionally, wild oysters are sold by the sackful to private customers. Aquaculture promises to make wholesale restaurant sales a lucrative endeavour. Marine extension scientists at the University of Georgia Shellfish Research Laboratory on Skidaway Island have been developing a line of endemic oyster seed that will mature into a marketable shape: a symmetrical, round, and clean product that entices on the half-shell, while retaining the classic Georgia briny flavor. Farmed oysters are raised in mesh bags that hang from suspended ropes or in cages that sit on the river bottom.

Harvesters skirt a steep bank along the Half Moon River as the evening tide empties into the Wassaw Sound. Using cat’s paws and other metal carpenter’s tools, the workers fill five-gallon buckets quickly, hoping to escape on the exiting tide before the sun sets.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

This essay first appeared in the Food IV: The Coast (vol. 24, no. 1: Spring 2018).

André Gallant is a journalist based in Athens, Georgia. He teaches at the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism and publishes Crop Stories, a literary journal critically exploring agriculture in the South. Learn more at www.andre-gallant.com.