Ethel Westbrook Guinn Williams moved north twice in her lifetime—once from around West Point, Mississippi, to Memphis, Tennessee, and the second time from Memphis to Detroit. She had two husbands, eleven children she raised mostly by herself in a little house she owned in Memphis, and a third-grade education, which she remixed with her own infinite know-how to make the best life possible for my Nana and her siblings. Even though she lived her last days on a farm three hours outside of Detroit, in a county that was more than 90 percent white and among the most politically regressive in Michigan, she, like most of my elders, had nevertheless worked hard to escape the South. We were never supposed to go back.

In 1990, the year my parents moved us from Detroit to Durham, North Carolina, I was a six-year-old blur of motion, restless for every adventure—up the street, across town, or five states away. I knew almost nothing about geography, but I was certain that every space was worth my time and attention. I had yet to learn that not every space was meant for me.

Great-grandma was right that we “didn’t know nothing ’bout the South.” We were no match for the thick July heat that greeted us in those first days—I could sweat the lotion clear off my face and arms just by sword fighting the sweetgum tree in the front yard. The sweet, heavy smell of curing tobacco still wafted through humid air downtown, the last gasp of the city’s iconic industry. My mom had to regularly explain to white grocery store clerks why my father’s name had an MD behind it on their Wachovia bank checks. I began school in the newly integrated public schools, the outcome of a long, bitter fight to keep the county white and the city as Black as necessary. In our tucked-away cul-de-sac not far from the county line, around the corner from a small cow pasture, our neighbors’ three-year-old once asked my father why he wasn’t white like her.

My parents thought we were just passing through for a few years—biding our time until we moved even further south to Atlanta—the Black metropolis. Meanwhile, I fell in love with my new home in the vast Durham forests. I spent hours in our shaded backyard, playing games around trees and trying to teach myself to start fires with broken branches. At school, Renise, Kaleshia, Yanumbe, Dennis, and I played kickball, four square, and handgames in our densely wooded park, across the street from our playground and an open grassy field where my teacher had us watch and sketch the clouds. But however I felt about this new place, these new smells, and new people, I remember how different it felt to visit “back home.”

What Great-grandma and her daughters built on many acres in the very white rural Midwest was a space of refuge, of collective sovereignty that she had not been able to keep in West Point, Memphis, or even Detroit, where her house was ultimately claimed by the state for a highway. That single row of modular homes bordering the woods was a world in itself, a place where my sisters, cousins, and I could pass hours running from house to house, eating bags full of cherries, and engineering a wagon to the biggest bike for our own roller coaster up and down the rolling grass hills. This place, more sacred to me than any church, was emblematic of the possibilities of Black geographies.

In the words of gender and geography scholar Katherine McKittrick and the late urban planning scholar Clyde Woods, Black geographies are sites that can trouble “dominant modes of geographic thought” predicated on colonialism, slavery, and marginalization, and “allow us to consider alternative ways of imagining the world.” The situatedness of Blackness as outside of dominant geographic thought precisely creates the possibilities of “our understanding of spatial liberation and other emancipatory strategies [that] can perhaps move us away from territoriality, the normative practice of staking claim to place.”1

Psychologically, spatial liberation for Great-grandma, in the end, had to do with leaving the South and painful memories that are lost to me. But spatially, it had everything to do with cocreating peace, safety, and love for generations of her family, even in the tiniest corner of a county that elected Donald Trump president exactly two decades after her death in 1996.

As we settled into Durham, a city bordering Stagville—one of the largest plantations in North Carolina in the colonial and antebellum eras—we found the spaces of refuge, of safety and love in the areas of the city carved out by people who were descendants of those enslaved at Stagville. We found sanctuary on Durham’s Southside, as members of St. Joseph’s AME Church, one of the anchoring institutions of Hayti, a Black community proudly named for the first independent Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. Like Great-grandma’s neighborhood in Detroit, Hayti was partially destroyed by a highway in 1970. But as I eventually learned for myself in more than thirty years as a southerner, and even longer as a US-ian—spatial liberation isn’t capital, territory, regionalism, or even ownership. It’s a praxis of spatial relations predicated on collective care that is, in the words of historian J. T. Roane, “capable of sustaining human relations and the biosphere.” Black geographies gives us the chance to revisit our relationships to space and place beyond the ways that we are conditioned—to possession, to exclusion, to fungibility, to profit. We are invited instead to consider the limitations of our conditioning and to experiment with imagining worlds different from this one—spaces without borders, reciprocal land relations, homes beyond property and valuation.2

This issue is a blur of motion through Black geographies of the global South. Together, we visit sites and mobilizations of Afro-diasporic peoples finding their way towards the praxes capable of sustaining life for themselves and all their relations. Priscilla McCutcheon and LaToya Eaves invite us to their rural Black geographies to demonstrate how the King James Version of the Bible, despite its colonizing power, was integral to the emergence of Black conceptualizations of spatial liberation and placemaking in the US South. Darien Alexander Williams reviews the global Black geographic imaginaries posited by the Nation of Islam in its short-lived publication Muhammad Speaks, which circulated widely in the Black US South, enticing young people like my great-aunt Inez McMann to flow north to Detroit to experience the empowerment and pitfalls of Black collectivism and nationalism. Javier D. Wallace reveals a whole world of southern HBCU basketball predicated on Black migration from Panama, and the promises and devastations that ensue from these stories of immigration, community building, and strivings for sports fame and fortune.

Quay Weston and Barbara Phillips both revisit their rural family home places and wonder how they can honor their ancestors’ relationships to the homeplace and create new relations and liberatory possibilities for generations to come. Sasha Ann Panaram takes us to Gloria Naylor’s imaginary Black geography of Willow Springs, a “fictional barrier island off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina that belongs to neither state” that is a primary setting of Naylor’s 1988 novel Mama Day. Suzanne Nimoh “rediscover[s] play in adulthood” with her transnational Black crip skater crew in Texas. And Ashanté M. Reese writes speculative fieldnotes of a Black neighborhood in Washington, DC, one hundred and two hundred years from one of her visits in 2016. In the tradition of what Kiese Laymon calls “black abundance,” we have even more to offer you online, as this issue could not contain all the brilliance, joy, and liveliness of southern Black geographies.3

Collectively, these stories, musings, speculations, inquiries, and reflections confront and deliver, in the words of folklorist and geographer Michelle Lanier, the sharpest “side-eye” to all the maps that hung in our classrooms, to all the visual, textual, and metaphoric ways that our Black lives and spatial practices have been disconnected from each other. This issue works to honor these tethers, to build on the work of McKittrick and Woods and to celebrate and imagine the possibilities of what sociologists Marcus Hunter and Zandria Robinson call “the enduring and overlapping connection that is Blackness and Black people here, there, and globally everywhere.” The space-time is also right, here and now. As we collectively witness and experience the deepening cracks in the infrastructures of racial capitalism and neocolonial globalism, Black geographies urges us to reflect on, retrieve, and rebuild our relationships to our ecosystems and to each other that are integral to our thriving. And in that process, perhaps we can, with joy and relief, practice letting go of the spatial relations and practices that hinder our liberation.4

This essay introduces the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 2: Summer 2023), guest edited by the author.

Danielle Purifoy is an assistant professor of geography and a faculty project lead of the Environmental Justice Action Research Clinic at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the racial politics and legal dimensions of development in Black towns and communities. She is the former Race and Place editor of Scalawag, a media organization devoted to southern storytelling, journalism, and the arts.

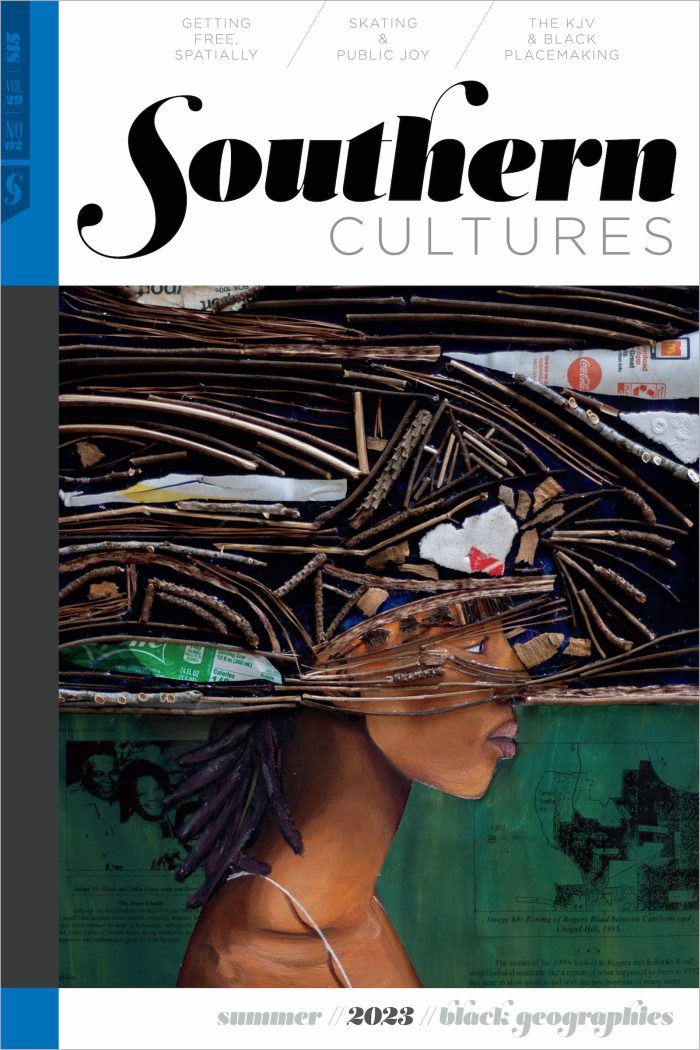

Header image: Detail from the Black Geographies cover art, Elements: Case Study, Rogers Road, by Claire Alexandre, 2020.NOTES

- Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods, eds., Black Geographies and the Politics of Place (Boston: South End Press, 2007).

- J. T. Roane, “Plotting the Black Commons,” Souls 20, no. 3 (2018): 239–266. I am thinking here particularly with my friend and collaborator, artist Torkwase Dyson, whose work “looks to spatial liberation strategies from historical and contemporary perspectives, seeking to uncover new understandings of the potential for more livable geographies,” website of Torkwase Dyson, accessed April 5, 2023, https://www.torkwasedyson.com/about1; Siddhartha Mitter, “An Artist’s Gateway to Freedom and Possibility,” New York Times, November 10, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/10/arts/design/13torkwase-dyson-pace-artist-architecture.html.

- Kiese Laymon, Heavy: An American Memoir (Simon and Schuster, 2018).

- Marcus A. Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson, Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018).