My great-grandfather was murdered by a white man in 1926, the night before New Year’s Eve. He was thirty-five years old—my grandmother Sara’s father. I call her Nana Boo. She doesn’t have any memories of him because he was killed when she was a baby. His wife, Nana Boo’s mama, Mary Jones Barkley, was the family matriarch who lived well into her nineties. Bluntly put, Ma Mary wasn’t with the shits: she kept her business to herself and expected her family to do the same. When Ma Mary said to do something, you didn’t ask questions. Nana Boo said when Ma Mary started moving furniture around the house, it was time for everybody to go home. Ma Mary worked for herself as a washer woman and a cook, refusing to clean white folks’ houses as a testament to knowing her worth. Before her death, Ma Mary met three new generations of Barkley babies. I was part of that last generation who met her, a girl great-grandchild with the memory of my Daddy sneaking me into her hospital room to see her one last time before she transitioned.

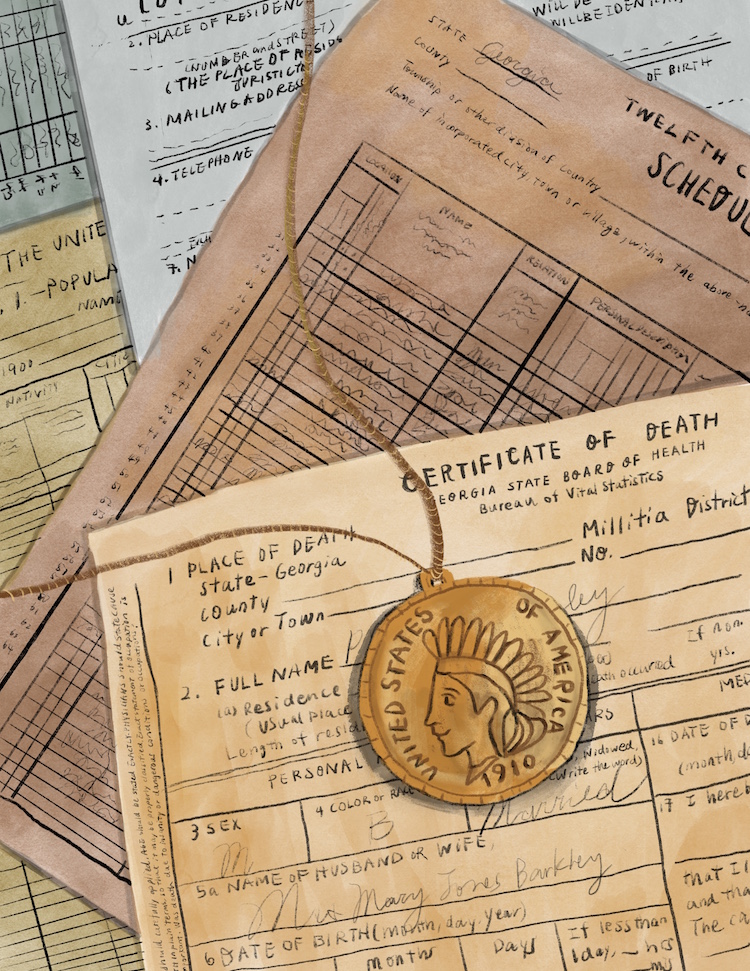

I was five years old when she died. Thus, Ma Mary Barkley was a tangible ancestor for me, buoyed in memory by Nana Boo and in the form of an Indian Head penny necklace that was once part of a pair of earrings that Ma Mary passed down to Nana Boo and Nana Boo passed on to me as a necklace. But my great-grandfather, Phill Barkley, was a ghost in my blood. I have honored and loved him because without him I wouldn’t exist, but I’ve also longed for him to be just as tangible and real to me as Ma Mary was. Phill Barkley has haunted me my whole life through snatches of him passed down to Nana Boo from the memories given to her by those who knew him. If I had to give a composite sketch of him, Phill Barkley was tall, fair-skinned, with light eyes and wavy hair. He was from Leary, Georgia, like Ma Mary. His mother’s name was Anjaline Green. He had a big sister, Sarah Green, who Nana Boo was named after. He was a logger and an entrepreneur in Ludowici, Georgia, where he was headed the night of his murder. I didn’t want to romanticize Phill, but I wanted to know more. Was he a jokester and storyteller like me? Did he laugh big and loud and make silly faces like my Paw Paw Eugene? Did he sing? Was his voice deep and velvety or strong and baritone? Perhaps above all else, when he looked at Ma Mary, did his eyes shine with love? What did he do to catch proud Ma Mary’s attention? These are answers I desperately wanted to know that squirmed at the foot of the graves of people who could tell me, like Ma Mary, or my great-great-grandmother Anjaline, or my great-great-aunt Sarah. When people asked me, “Who your people ’nem?” I wanted to boldly and fully include Phill in my answer.

I didn’t want to romanticize Phill, but I wanted to know more. Was he a jokester and storyteller like me?

When southern black folks seek each other out, the quickest way to size someone up is some iteration of the question “Who your people?” This question initiates conversations among many southerners, but the simple question is one of the heaviest a black southerner can ask. It bridges southern black folks from the past to the present, beckoning forth people who have been lost on the ancestral and historical plains to take a step closer to being seen and remembered. I think about the newly emancipated black folks passing each other by searching for loved ones; the folks coming South for the first time and being checked out by the local people to invest or reject the stock of the newcomer; the need to identify a body or a soul taken away too soon. In being asked “Who your people?,” the weight of historically and culturally being seen pivots off the need to be rooted in a community. For me, when I was asked who my people were, the answer to the question always rolled off my tongue like well-seasoned pot liquor: “My folks is the Barnetts from Albany and the Barkleys and Joneses from Leary.” Most of my people were well loved and accounted for because I spoke their names fervently, often drawing on the stories my Nana Boo and Paw Paw told me.

From this perspective, I often think about the question “Who your people?” as a testament to the hard-fought ties of family and community that are the lynchpin for understanding the Black South. Additionally, the gatekeepers and legacy makers of the Black South are black women. Black women often passed down what they could—whether a name, a song, or a piece of something like an Indian Head penny—to preserve a little bit of themselves for future generations to see and know them. I learned at an early age about the difficulties of sustaining a legacy for black southerners. It is a strong held belief that the crux of southern blackness is trauma as a residual action and as memory. However, southern black folks’ legacies hide in our hearts, our laughter, our rituals, our kitchens, and in our hope for ourselves and each other. Southern black people spoke and conjured themselves into existence and spaces where white folks wished we crawled under rocks and porches and shrank ourselves out of a complicated existence. Even if it was bit by bit, fragmented memory by fragmented memory, I would snatch Phill Barkley back from the dried-out jaws of an unknown past and get to know him better. To borrow from and remix a well-worn African proverb, I wanted to tell the lion’s side of the story now lost to history, un-glorifying the white man who peacefully and quietly lived his life after violently ripping apart the lives of Phill’s family—my family. Me, the lion’s great-grand cub, determined to reshape Phill Barkley’s story nearly a century after his death.

The gatekeepers and legacy makers of the Black South are black women.

The Search for Paw Paw Phill

I first attempted to search for more information about Phill Barkley back in 2011 when I fell down the rabbit hole of an Ancestry.com free trial weekend. It was a welcome break from the grind of dissertation writing that was running me ragged. My search only yielded surface-level results from available census records that were not behind a paywall. 1920 found him married with two kids, living in a rented house with boarders. The only other evidence I discovered was his death certificate, a sloppy and hastily written account of the day his life ended in Albany on December 30, 1926. I was fascinated—obsessed even—with my inability to read the cause and location of his death. In hindsight, the certificate was a physical signifier of the illegibility of his humanity as a black man in the Deep Jim Crow South during the early twentieth century. The voice Phill was speaking with was not his own—it was his sister Sarah battling the coroner. On the left side of the document, Sarah added whatever lifelines she could to her brother after his death: his parents’ names and his marriage. Hell, just showing up to identify him as a loved one counted. On the right side, the coroner’s scraggly and un-invested handwriting said when he died and that an operation was performed in an attempt to save his life, but that he ultimately succumbed to an infection from a laceration on his neck.

My family and I had long held tight to an explanation, passed down through word-of-mouth, that Phill died because he was a black man who owned a car and a white man deemed him being “uppity” and above his station. But I now wondered if that was really it. Could Phill’s success as a black man who worked for himself set off the man who sliced open his neck like Ma Mary and Nana Boo believed? Reviewing the death certificate, my whole body bristled at the quickly scrawled and casual nature of a statement that proclaimed he died from an infection rather than an act of racially motivated violence. I wanted there to be an additional box to explain how he died for real. “Well, I seriously doubt they would give the actual reason for his death, sweetheart,” Nana Boo told me. “White folks could put whatever they wanted on those things and it would be taken as fact.” I didn’t know how to respond after that, so I used the best filler I could: “Yes, ma’am.”

Eight years later, dissertation long submitted and out of my life, Phill Barkley started to poke and prod at my spirit once more. As I approached my own thirty-fifth birthday, I felt his presence more strongly and decided to take another look into his life and death. But this time around, I nicknamed him Paw Paw Phil to make him more tangible. I reached out to a friend, JoyEllen Williams, an archivist at the university where I work, and she put me in touch with Tamika Strong, a reference archivist at the Georgia Archives with an emphasis on genealogy. Before we met in person, Tamika sent me a zip file of all the information she could find on Paw Paw Phill. I hesitated to open the folder, afraid that what I thought I knew about him would crumble, or that I would I hurt my grandmother with this new information. What I found inside were census records from 1900, 1920, 1930, and 1940; Paw Paw Phill’s draft card from 1917; and the 1940s draft card of Paw Paw Phill’s son. There was also a census record of Ma Mary from 1910 before she was married. I read each line over and over, as if conjuring the documents to talk to me and tell me the secrets hidden in plain sight about my great-grandfather.

After hugging Tamika’s neck while holding back tears at the Georgia Archives, she walked me through the basics of genealogy research. Tamika explained that census records are always a good place to start, but warned me about the need to fact check with folks in the family. According to her, census takers often gathered information from neighbors and other people who might know people in the household in question, writing down nicknames, maybe birthdays and jobs, and other tidbits of information to round things out. Census records, I quickly came to understand, act as a slice of humanity for the people recorded on the ledger, and also act as multiple genesis points for understanding who they were. This is especially amplified in thinking about the sonic reckonings that census records provide—for instance, the phonetic spellings and pronunciation of names and how those names were written down. I hadn’t previously considered how dialect cemented historical records in the Deep South. On his draft card, Paw Paw Phill spelled his last name “Barclay” instead of “Barkley,” the way Ma Mary and Nana Boo spelled the last name. I can’t help but imagine the thickness of Paw Paw Phill’s southwest Georgia accent as he explained to the military registrar who he was as he registered for World War I. Additionally, I was intrigued by the multiple ways Paw Paw Phill’s name, and even Ma Mary’s names, were spelled. There was also other contradictory information about their lives, such as Paw Paw Phill’s birthday, listed as both April 1890 and May 1891. His death certificate solidified his birthday as May 1891, and his draft card further confirmed May 29, 1891.

Census records, I quickly came to understand, act as a slice of humanity for the people recorded on the ledger, and also act as multiple genesis points for understanding who they were.

As we worked, more questions were raised than answers about Paw Paw Phill: his mother Anjaline and sister Sarah’s last names were Green. Who was Tom Green, Paw Paw Phill’s stepfather? Who was the mysterious man Bill Barkley, listed on Paw Paw Phill’s death certificate as his father and known with hushed tones around our family to be a white man? What was their relationship like? It might’ve been pretty good, considering that Paw Paw Phill named his son Coley Bill Barkley. (Coley, who went by “C. B.,” was Ma Mary’s daddy, who lived on through his grandson). How did Paw Paw Phill go from being a fanner—a farm worker who separated chaff from harvested grain—to a logger with a stake in a logging company? And, above all, what were the details of the trial for the man who murdered my great-grandfather?

I dressed up everything I had gathered on Paw Paw Phill and shared it with Nana Boo as part of her Christmas gift that year. Wide-eyed, she nodded and said, “Oh!” and “Sho nuff?” as I showed her the various records. She smiled at me but didn’t speak after my presentation.

“Nana Boo? You alright?”

“Arthur Tyson,” she said softly.

“Ma’am?”

“Arthur Tyson. That was the man’s name who murdered my daddy,” she said. “We went to his trial in Morgan but when he was shown not guilty Mama picked me up and ran out the courthouse.” A not guilty verdict for the man who murdered her father was the last and possibly only memory Nana Boo had of Paw Paw Phill.

Arthur Tyson. That name had probably not been spoken by anyone in our family for over three-quarters of a century. I opened a sticky note on my phone and jabbed the letters spelling his name into my phone.

My great-grandfather was murdered by a white man named Arthur Tyson in 1926 the night before New Year’s Eve.

He was thirty-five years old.

I am his great-great-granddaughter. I will tell his story. ’Cause he my people ’nem.

This essay first appeared in the Backward/Forward Issue (Spring 2019).

Regina N. Bradley is a writer and researcher of contemporary black life and culture in the American South. She is the author of Boondock Kollage: Stories from the Hip Hop South. She is an alumna Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow at Harvard University and an Assistant Professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at Kennesaw State University. She can be reached at redclayscholar.com.