“When train number nine on the Western North Carolina Railroad tumbled off Bostian’s Bridge in 1891, it ignited a media frenzy, as well as a firestorm of outrage, a detailed investigation, a compelling mystery, and a series of unanswered questions.”

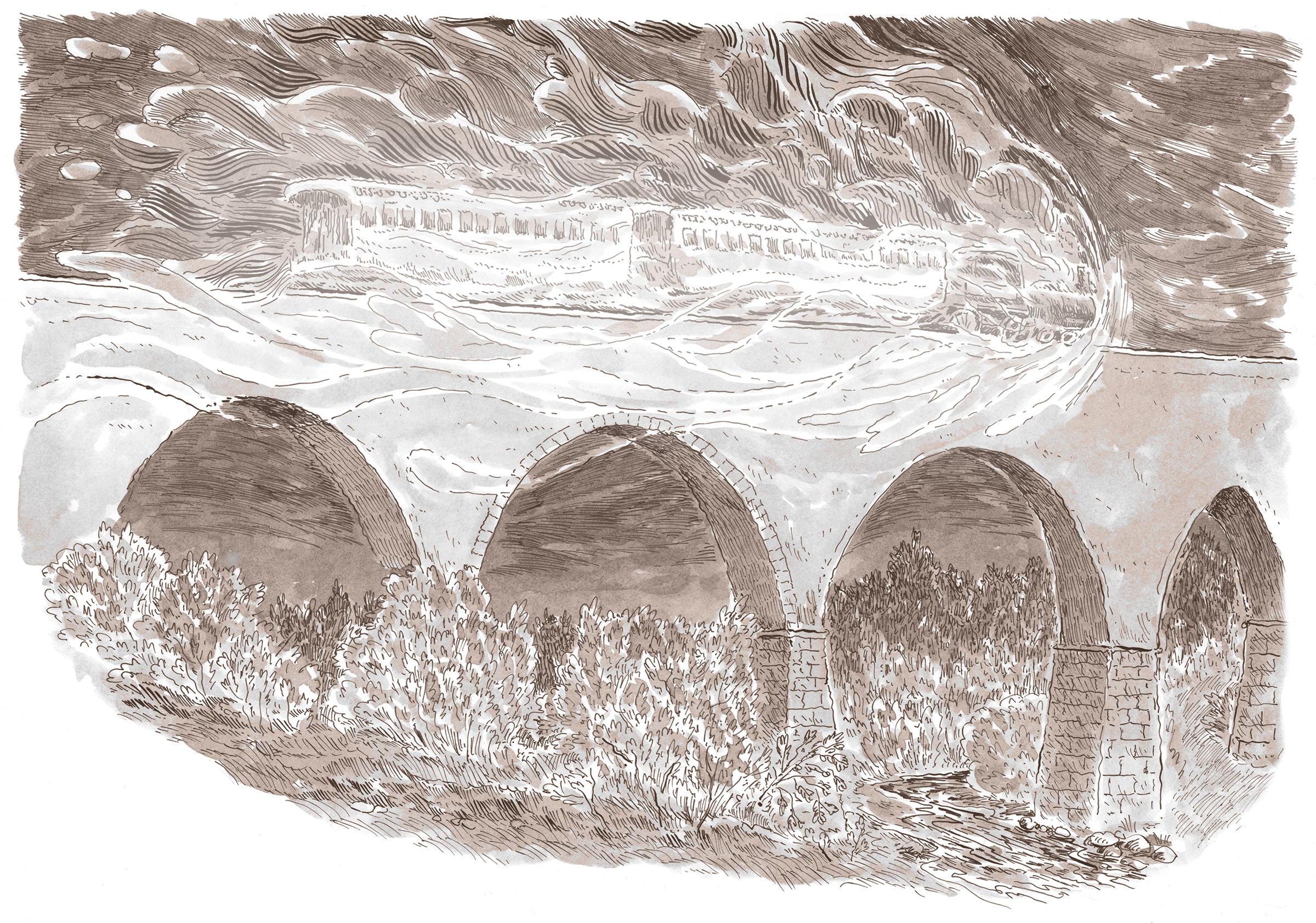

Norfolk Southern locomotives still rumble periodically over Bostian’s Bridge trestle, a 300-foot long stone bridge that rises 30 feet off the ground near Statesville, North Carolina. But supposedly, those aren’t the only trains on the track. As legend goes, on the anniversary of a wreck that occurred at the site on August 27, 1891, a ghost train hurtles off the bridge and crashes to the ground below. Visitors have claimed to see a uniformed man with a gold watch, or to hear the screams of doomed passengers and the clang of crashing metal. Statesville has thus played host to hordes of ghost hunters and paranormal researchers, who converge on the site every August 27 hoping to catch a glimpse of the haunted train. In 2010, tragedy struck the annual gathering when a party of ghost hunters encountered an actual freightliner barreling down the track. The group fled, but one man was struck and killed.1

The accident garnered national attention, but was hardly the first event to put Bostian’s Bridge in the news. When train number nine on the Western North Carolina Railroad tumbled off Bostian’s Bridge in 1891, it ignited a media frenzy, as well as a firestorm of outrage, a detailed investigation, a compelling mystery, and a series of unanswered questions. Just what had caused the train to derail and who was ultimately responsible for the twenty-two deaths that occurred? Was it the railroad’s fault for poor maintenance of the bridge, or had a gang of robbers removed a rail to deliberately wreck the train and rob the passengers? Regardless of the source, southerners were haunted by the wreck at Bostian’s Bridge and the idea of train wreckers—gangs or individuals who intentionally derailed trains and threatened the region’s railroads in the 1890s.

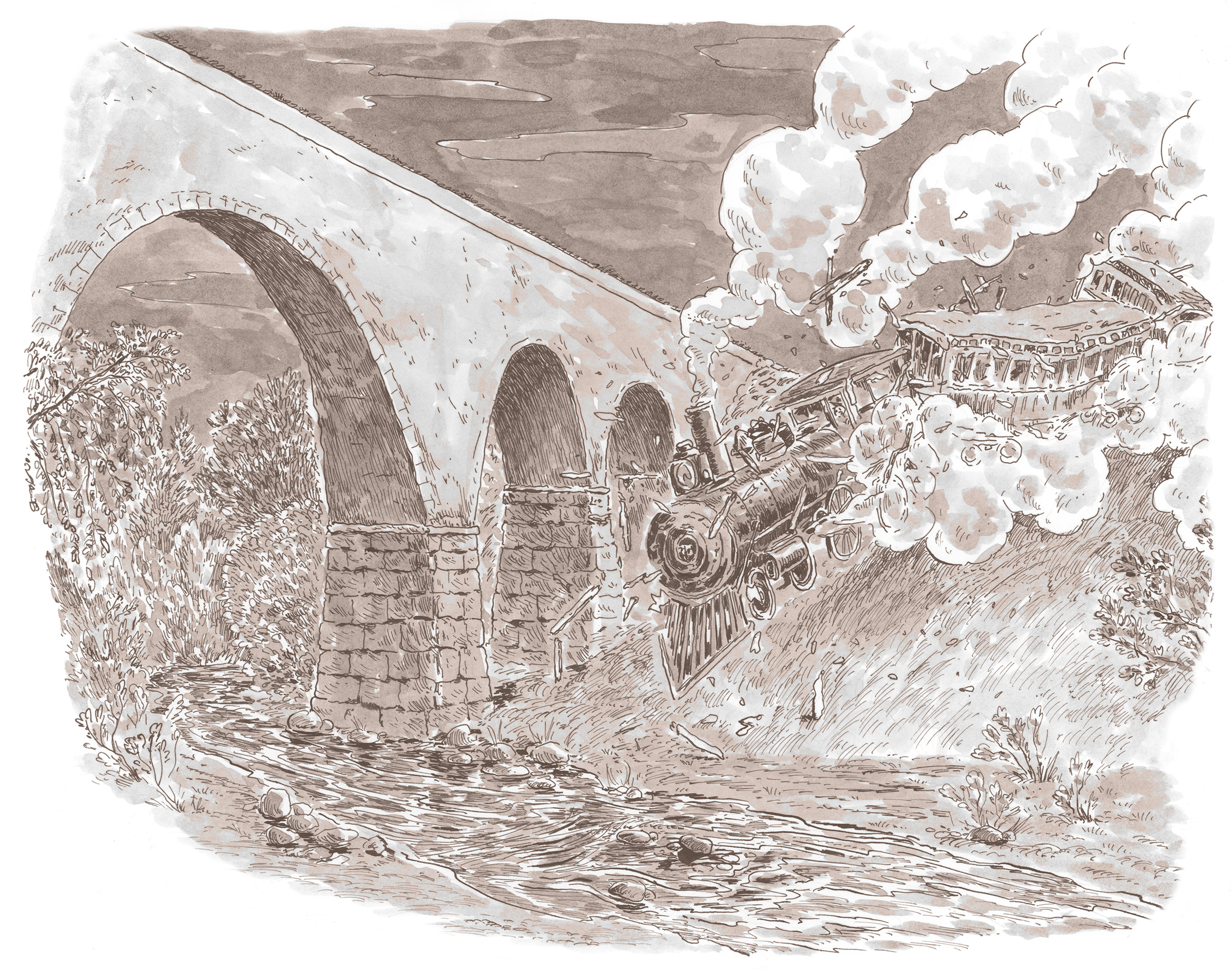

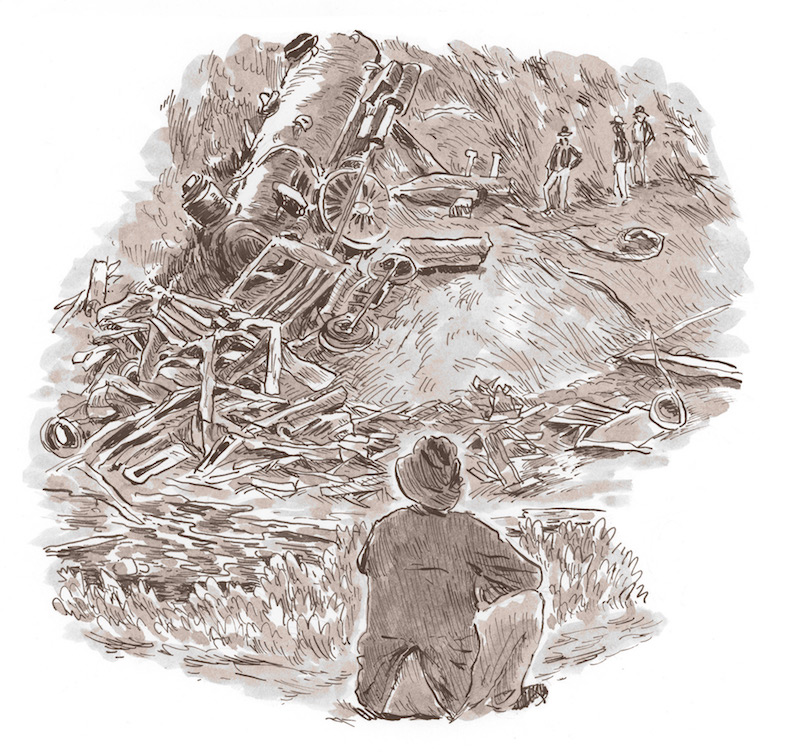

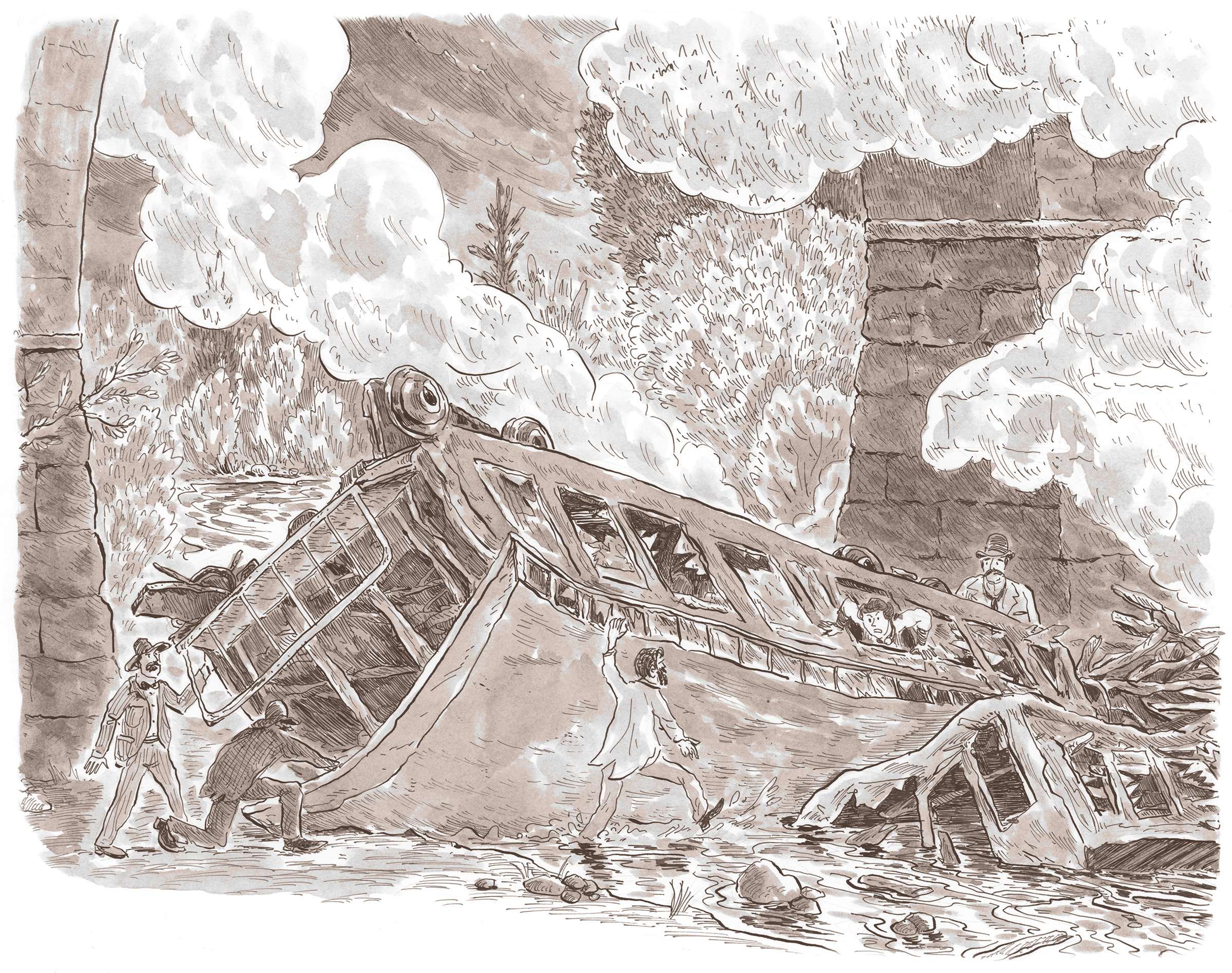

The basic facts of the disaster were clear enough. In the middle of a hot August night in 1891, train number nine, heading west toward the mountains on the Western North Carolina Railroad, pulled into Statesville an hour later than scheduled. Ten new passengers boarded the train. Then five minutes after it left the station, riders experienced a jolt and falling sensation as the freight tumbled off Bostian’s Bridge and dropped 60 feet into the creek below. Statesville citizens rushed to the disaster where morning’s light revealed a ghastly scene. As the Statesville Landmark later described, it was “a charnal-house in Third creek on its banks.” Early responders encountered “a harrowing spectacle and harrowing sounds” near the engine, which was turned on its side just to the west of the stream. In the water, the first-class car was piled on top of the combination second-class and baggage car. Killing twenty-two, it was the deadliest train wreck to date in North Carolina.2

The Most Commanding Theatre of Capital

The wreck at Bostian’s Bridge occurred at a critical moment in the history of capitalism in the South. The gospel of the New South, which promoted industrial development, aggressively sought infusions of northern capital, and advocated a break with the patterns of the antebellum agricultural economy, was sweeping the region. And for New South boosters, the expansion of the region’s railroad network provided the most tangible example of southern progress. Between 1880 and 1890, the South’s railroad mileage almost doubled. In North Carolina alone, it expanded from 1,486 to 3,128 miles, providing countless communities a connection to the national rail network. M. B. Hillyard, writing in a special 1887 edition of the influential booster publication Manufacturer’s Record, called southern railroad development “the most commanding theatre of capital” which “strikes the eye of the world not only for its colossal combinations of money, but the prestige of its participants.” According to Hillyard, the South’s rapid rate of railroad construction was “proof of development and of the confidence of the capitalists of the civilized world.”3

The New South boosters fused economic growth with a powerful cultural narrative of regional redemption, but, by 1891, not all were in agreement about the implications of this economic transformation. Groups like the Farmer’s Alliance and the Knights of Labor offered a counterargument that lamented the increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of so-called robber barons, attacked the ascendancy of large corporations, and testified that the system exploited farmers and workers. To challenge those issues, such groups often touted a state railroad commission. But in North Carolina, the 1888 legislature debated and ultimately defeated a bill that would create one. By 1891, however, a state legislature in which 110 of the 170 members were backed by the Farmer’s Alliance formed a railroad commission whose goal was to reduce rates. In its infancy, the power and duties of the commission were unclear, thus, the aftermath of the wreck at Bostian’s Bridge became crucial in determining the direction the group would take.4

The Western North Carolina Railroad that connected Statesville with Asheville was publicized in promotional literature as an idyllic route to the “Land of the Sky,” but the road had a checkered past. Chartered in 1855, the route was not completed until 1880 after the state of North Carolina deployed convict laborers to grade and extend the road to the Tennessee border. With 500 workers blasting through, around, and over mountains, the construction of the road itself was marred with tragedy. A cave-in at Swannanoa Tunnel, later immortalized in folk songs including “Swannanoa Tunnel” and “Asheville Junction,” killed twenty-one workers, and at least 125 convicts died over the course of construction. Financial woes also plagued the line, and eventually it fell into receivership. A New York businessman bought the road from the state in 1880 and immediately assigned his interest over to the Richmond Terminal group. The Richmond & Danville system formally leased the road in 1886, folding the Western North Carolina Railroad into a growing collection that would eventually become the Southern Railway in 1894. Statesville and its railroad thus became part of a larger system that spanned the South and was controlled by Richmond managers and New York bondholders.5

The Bostian’s Bridge wreck—its grisly details sprawled across front pages of newspapers—provided a moment of reflection that threatened to undercut the claims of the New South boosters and to severely damage the South’s newly ascendant railroad corporations. In the immediate aftermath of the wreck, North Carolina editorialists offered systemic critiques similar to those leveled by the Farmer’s Alliance and its allies. For instance, the Charlotte Chronicle argued, “in this great system many lives are hung upon the many liabilities of a great army of employees.” The Greensboro Patriot expounded on this idea, saying, “there is not the same care for human life as displayed in other countries. Railroads are too eager to declare big dividends and too many risks are taken.” In addition to pointing out flaws in the track, the Greensboro paper also blamed the railroad for running a train too fast over Bostian’s Bridge. The Concord Weekly Standard went further, invoking the wreck to attack the railroad authorities’ inflated position, saying, “when you thrust power upon some people they become tyrants, bigots, and, in plain English, fools. The influence of such men has led the masses to seek redress by law for the slightest grievance.” But the wreck at Statesville was obviously more than “the slightest grievance,” so the paper predicted that the current “boiling and sizzling” was “only a forerunner of what [was] coming.”6

An investigation of the wreck’s cause thus proceeded in a charged atmosphere with high stakes for the Richmond & Danville Railroad and broader agendas of economic development in the New South. Inquiry first fell to local authorities, specifically the Iredell County coroner’s jury, which interviewed more than 40 witnesses. The testimony, printed in full in the Statesville Landmark, revealed a chaotic scene, but two clear versions of the wreck emerged. The first faulted negligence by the railroad. As evidence, Col. S. A. Sharpe described rotten piles of timbers around the scene, explaining, “you could kick them to pieces . . . occasionally you could find a sound one but not many.” W. A. Eliason similarly noted rotten cross ties that “should not have been on any track.” After cross-examination, he estimated that about half of the track’s crossties were unsound and said he had found no evidence that a rail had been removed or spiked. He concluded his testimony with the caveat, “I have no feelings of animosity against the railroad except in regard to the accident.” R. B. Linster said that as soon as convicts employed by the railroad to clear the scene arrived, he “noticed that they were throwing broken crossties off the bridge into the creek, many of them looking mighty shackling.” Five other witnesses besides Linster also claimed to see convicts toss rotten timbers into the creek below.7

The Richmond & Danville presented its own version of the wreck, aided by a cadre of lawyers the company had sent to Statesville. If the railroad could prove that wreckers had deliberately derailed the train, the company would not be found negligent and would not be responsible for paying damage claims, which were inevitably filed by both injured victims and family members of the deceased. Testimony from the Iredell County coroner’s jury clearly identified witnesses introduced by the railroad company, which made obvious the railroad’s intentions. D. L. Hutter claimed to see spikes on the track, W. G. Wright saw some spikes and “evidence of wrecking,” T. J. Allison found a warped rail that he thought the engine passed over, and Bennehan Cameron noticed a detached rail. L. Kale, the road’s section master, said he hadn’t worked on the road for a month, but he thought that it was sound. And though his tools were in his house, he speculated that someone could have gone in and taken them since the door was unlocked. Beyond pointing to physical evidence, some railroad witnesses went as far as suggesting potential culprits. Two individuals spoke of a mysterious white man in a black suit and a black slouch hat who had been seen around Statesville before the wreck.8

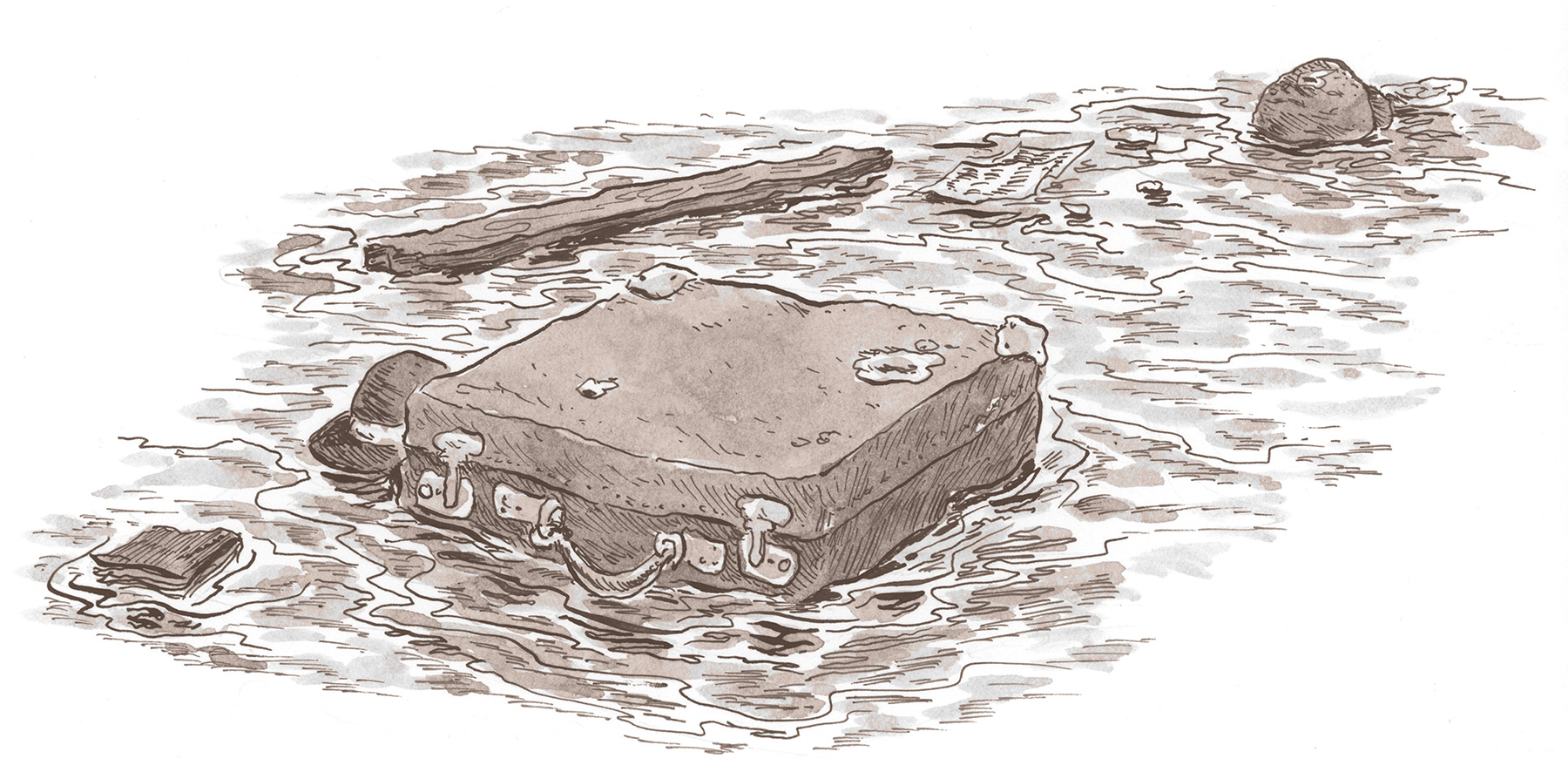

Other railroad witnesses pushed the idea that robbers had wrecked the train. Mrs. Moore, a passenger, testified that when she got out of the ruined train, a diamond pin that she had been wearing earlier was gone, as was a check for $200 and a note for $2,000. Another passenger, Miss Luellen Pool, said that as she lay in the cars, a man with a hat pulled over his face crept along the top of the car and put his hand in the window “as if feeling for something.” After a fellow passenger asked him what he wanted, the man “left creeping away.” In the same car as Miss Pool, Col. Sanderlin awoke to find a black man in his early twenties staring at him through the window making “suspicious movements.” After the man would not respond to Sanderlin’s queries, Sanderlin said it “instantly dawned on [him] that he came there to rob us.” Passenger Henry Demming spoke of two black men who approached the wreck from Statesville, and a man with “African blood” moving very deliberately around the scene of the incident. As Demming described, he was “the coolest man I ever saw,” and he “asked no questions and seemed to be helping no one.”9

The notion that someone would deliberately wreck a train did not emerge at random. Combatants from both sides of the Civil War targeted rail lines, and folks like Jesse James, who made a living robbing trains in the 1870s, became household names. Making use of these ideas, southern railroad lawyers increasingly blamed accidents on wreckers to escape liability during the 1890s. When a Southern Railway passenger car crashed through an open switch in Scotland, Georgia in March 1895, the accident sparked a lengthy trial in which the railroad’s lawyers tried to prove train wreckers had caused the calamity. As a reporter noted, the railroad “would be relieved of all responsibility if the alleged wrecker is finally convicted in higher court.” The Louisville & Nashville Railroad resorted to an even more pernicious tactic after an 1896 wreck near Birmingham, Alabama killed twenty-seven. The road’s lawyers and investigators deliberately concealed construction errors that led to structural flaws in the bridge design.10

Suggestions of a planned robbery at Bostian’s Bridge fixated on the presence of mysterious African American men who descended on the scene after the wreck, but the four black men who testified before the coroner’s jury, Henry Nesbit, Henry Hart, Joe Chambers, and Jesse Freeze, offered a much different take on the matter. According to Nesbit, he hurried to the bridge after hearing a crash and encountered “some big fat man” who was “calling for his gold specks, gold cane and hat.” Chambers also saw “some old fat man.” As Chambers recalled, he was sitting on a young lady and “did not want to move. He did not want to come out of the car.” When rescuers finally began to remove him from the train, the man asked Chambers to “stop until I get my umbrella, walking stick and spectacles.” Nesbit says he found an axe and used it to cut a man free. He saw no one robbing the cars, and saw no mysterious strangers. Hart said he met Nesbit on the way to the wreck, where he helped free wounded and dead passengers from the train. Freeze claimed to see several men entering the ruined cars, but explained that instead of robbing passengers, they were merely trying to get victims out of the cars, which were rapidly filling with water from the creek.11

The fat man turned out to be none other than Col. George Sanderlin, who was so insulted by the testimony that he sent a letter to the State Chronicle, which was reprinted in papers across North Carolina. He denied sitting on a lady, instead claiming he was resting on a mattress after Bennehan Cameron, not Chambers or another black man, pulled him out of the wreckage. He argued that the testimony about his concern for his personal effects was exaggerated, and that he only wanted to get the cane since it was valuable. Building on that idea, Sanderlin suggested that the black men wanted him to leave it behind so they could steal it. He further defended his actions saying he needed his pants because it was cold, and his glasses since he was nearly blind without them. He concluded his letter by saying, “[I] received many painful wounds and bruises in the wreck, but not one has hurt me so much as the picture drawn of my inhumanity and of my great concern over small things.”12

A report by the Iredell County coroner’s jury did not commit to a cause of the wreck. The report largely agreed with the railroad’s version, saying it was “caused by a loose rail, the bolts and spikes of the same having been taken out by some person or persons unknown to the jury, with tools or implements belonging to said railroad company.” But the verdict also accused the railroad of “gross negligence” for leaving tools in an accessible shed. In addition, the jury ruled that several crossties near the break in the track were “unsound and should have been replaced,” and that the train was probably moving too fast over the precarious bridge. A paper later reported that juryman J. S. Ramsey signed the report, but did not believe that any rail was removed or misplaced before the wreck.13

To offer a final official verdict on the wreck’s cause, the North Carolina Railroad Commission also conducted an investigation. Foes of the railroad had hoped that this body would take a strong lead in the inquiry, but its makeup precluded any chance of an impartial investigation. Before it even started, Lead Commissioner James Wilson told a newspaper that there was no way the track could have failed. His confidence in the road was not surprising, as he had once been the president of the Western North Carolina Railroad. Not only had he made the original surveys for the road across the state, but he had also supervised the construction of Bostian’s Bridge. It is no surprise then that he found no reason to suspect faulty construction or engineering work on a road that he had built. On September 10, two weeks after the wreck, an article printed in the Charlotte News and reprinted in a number of other papers seemed to settle matters once and for all. The article reported that members of the Railroad Commission and officials from several major railroads had met and concluded that a rail had been removed at a critical point, thus leading to the derailment. “There seems to be no further doubt about the Statesville disaster,” the article claimed. With that final declaration, the debate was seemingly over.14

But many Statesville residents were unconvinced. The Statesville Landmark continued to dispute the notion that the train was wrecked, arguing that “when the news got far from home and was doctored in central offices . . . it began to take on a different complexion.” The paper termed the suggestion that people from Statesville had robbed passengers “outrageous libel.” To help their case, the railroad attempted to track down the wreck’s responsible party, aided by the Richmond & Danville, which offered a highly publicized $10,000 reward for the arrest and conviction of anyone connected with the wreck. A detective hired by the railroad wrote a letter to survivors asking if they had any disagreements with friends who could have plotted revenge, or if they lost any valuables in the wreck. These attempts to find a culprit led to a few arrests of suspicious-looking individuals, but the investigation ultimately fell short. About a year after the wreck, the Landmark’s editor wrote, “the contention of The Landmark has been that the train was not wrecked, and we are satisfied, in view of the railroad company’s ridiculous failure to make it appear that it was, that the public believes by this time that The Landmark was right.” On the seventy-fifth anniversary of the wreck, Statesville’s newspaper noted that the cause of the wreck was still “controversial.”15

The diary of David Schenck, the Richmond & Danville’s head lawyer on the case, also suggests that the wrecker story was a fabrication. After the Richmond & Danville system was reorganized as the Southern Railway in 1894, Schenck was forced out of his position—a move he attributed to his reluctance to carry out his duties after the Bostian’s Bridge Wreck. As lawsuits for damage claims wound their way through North Carolina’s courts, the company tried another common strategy to contest the claims: move them from the local courts so they would not have to deal with a jury whose community had been traumatized by the wreck. For the Richmond & Danville, this meant a shift from the Iredell County courts to the Circuit Court in Charlotte. Schenck wrote in his diary that he would not swear to the petitions for the removal of the cases “because they contained falsehoods.” Unfortunately, he didn’t elaborate on the character or source of such fabrications. Still, the entry shows that even an experienced railroad lawyer harbored doubts about the company’s tactics.16

Despite the fact that the cause of the disaster was unsettled, the wrecking and robbery theory gained the widest purchase. S. P. Read, a Memphis man whose daughter died in the wreck, wrote Bennehan Cameron asking for details about his daughter’s death “down to the minutest details.” From what Read had heard, his daughter had survived the initial collision and was freed from the wreckage by Cameron, who later returned to the scene to find her dead. Read suggested in his letter to Cameron, “during your chance when you left to ring the alarm at Statesville, some villain may have murdered her to take from her person the insignificant valuables she possibly had.” Read’s assumption that robbers killed his daughter may sound sensational, but the fact that Read could even consider such a crime speaks to how compelling the railroad’s narrative of wrecking and robbery was for those in search of cause and meaning.17

Backed by the weight of a powerful corporation with allies in the highest levels of state government, it is no surprise that southerners largely accepted the railroad’s narrative of wrecking and robbery. White southerners were on edge in 1891. Increased mobility introduced by the interconnected rail network meant more frequent encounters with strangers, such as the white man in the black slouch hat seen lurking around Statesville, and unfamiliar black faces, like the four rescuers. This dynamic helped fuel an outburst of lynching in the 1890s, which historian Amy Wood has argued “erupted and thrived along the fault line where modernity and tradition collided.” Just as white men mobilized to confront the threat of supposed black rapists, white rail passengers began to fear conspiracies behind wrecked trains, and worry that gangs lay in wait at trestles like Bostian’s Bridge.18

Editorial pages initially focused on the broader systemic flaws behind the wreck. However, a number of papers clearly changed positions in light of the intimation that wreckers caused the accident. In the first issue published after the wreck, Leonidas Polk’s Progressive Farmer, a Populist publication that was typically hostile towards rail corporations like the Richmond & Danville, noted that whatever the cause, “it does not do away with the idea that every high bridge ought to be inspected before crossed by a train, and that trains ought to be run over bridges at a very slow rate of speed.” The paper went on to say that the practice of trains trying to make up time by running fast should be “stopped at once.” But after the coroner’s jury report, the paper switched tack and defended the railroad, arguing, “it is absurd to say that they carelessly allow anything to occur that entails such a great loss.” The paper suggested that the “well-dressed stranger” was the culprit—a “Jack the Ripper kind of fellow who thinks his mission here is to wreck trains.” A mere day after the paper printed an editorial suggesting safety improvements, the Richmond Dispatch noted that train wrecking had become too common, a “menace to all who ride upon railroads” and that to “flay them alive would be all incommensurate with the condemnation due their dastardly deed.” The rhetorical fire of editorial pages, once trained squarely at the Richmond & Danville or at the broader railroad system, was clearly redirected towards the unidentified wreckers.19

Beyond Bostian’s Bridge

Though an accidental derailment, not a gang of robbers, seems the most likely culprit, we will likely never know the real cause of the wreck at Bostian’s Bridge. Sadly, the tragedy was not an isolated incident, and the rapid growth of the southern railroad network was accompanied by increasing carnage on the South’s rails. Data from the Railway Gazette shows a steady climb in southern train wrecks from 1878 through the end of the century. Nationwide, the years between 1890 and 1893 were particularly fraught with accidents. While some of this increase correlates to the growth in railroad lines, Mark Aldrich, a historian who tabulated railroad accident statistics, blames the rise specifically on “the construction of flimsy railroads in the South and West.” When broken down by region, the South’s “flimsy” railroads consistently ranked as the deadliest in the nation for both passengers and employees. The Interstate Commerce Commission concluded in an 1891 report that travel in the South was more dangerous than in any other area of the country. The Commission began tabulating more comprehensive data in 1892, and it found that compared to travelers in the rest of the country between 1892 and 1900, a passenger on a Deep South railroad was about 2.48 times more likely to be killed and 2.76 times more likely to be wounded. A passenger on one of the Upper South’s railroads was 1.84 times more likely to die and 2.3 times more likely to be injured. Train wrecks and other transportation disasters had long horrified the public, but a series of new factors in the 1890s—a sensationalist press, a more interconnected rail and telegraph network, and increasing frequency of disasters—combined to heighten their impact, especially in the South.20

This dark side of southern railroading posed a serious dilemma to advocates of the New South gospel, as it was tough to reconcile a bloody reality with a message of economic progress. On a basic level, the strategy of blaming train wrecks on anonymous wreckers was a way to escape the financial liability of damage suits and to avoid the political and regulatory consequences of a serious investigation by bodies like the North Carolina Railroad Commission. But imaginary train wreckers also helped the railroad retain its symbolic power as the savior of the New South. By holding tramps or unrecognized black men responsible for horrific train wrecks like that at Bostian’s Bridge, the railroad was spared some outrage and sometimes even held in heroic regard. In the end, the notion of train wreckers served as a red herring, distracting from more significant structural problems with the operation of southern railroads, and forestalling more serious attempts at regulation.

A newspaper correspondent riding in the cab of a fast mail train leaving Meridian, Mississippi in 1892 was overcome with fear and described “visions of train wreckers galore” as his train rumbled through the night. Similar descriptions of “wreckers galore” filled the pages of southern newspapers. Between 1878 and 1900, over 200 articles in the Atlanta Constitution blamed train wrecks on wreckers with malicious intent. Wreckers even appeared in advertisements, as seen in an ad from 1898 for consumption medicine printed in Raleigh’s News & Observer. Some, like the skeptical locals in Statesville, realized the illusory nature of the threat. After an Alabama wreck in 1896, a man writing to the local paper claimed that wrecks were simply bound to happen as a matter of course. But afterwards, he noted, “the railroad men, to keep their road from being liable for damages, tell the newspaper correspondents that train wreckers did it. The correspondents, always on the lookout for a sensation, telegraph the papers in other cities” and readers assume that “fiends in human form” caused the wreck. Today, a notion of spirits continues to spur interest in Bostian’s Bridge—particularly after the 2010 tragedy that occurred there. But the trestle’s current status as a haunted scene and a tourist attraction for ghost hunters obscures traumas associated with the arrival of a systematized railroad network in the 1890s, including fears of wreckers who menaced southern rail lines to the “Land of Sky” and beyond.21

This article first appeared in our Summer 2014 Issue (vol. 20, no. 2).

Scott Huffard is Associate Professor of History at Lees-McRae College in Banner Elk, North Carolina. He earned his PhD in History from the University of Florida in 2013. His work has also appeared in the Journal of Southern History, and he is currently working on a book manuscript on railroads, capitalism, and the mythology of the New South.NOTES

- Phil Ghast, “‘Ghost train’ hunter killed by train in North Carolina,” CNN, August 28, 2010, accessed August 23, 2011, http://edition.cnn.com/2010/US/08/27/north.carolina.ghost.train/index.html; Jim Mcnally, “Bostian Bridge legend drew ghost hunters,” Statesville Record & Landmark, August 30, 2010.

- “The Story of the Wreck” Statesville Landmark, September 3, 1891.

- John E. Stover, Railroads of the South, 1865–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), 193; Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992) 9–13; M. B. Hillyard, The New South: A Description of the Southern States, Noting Each State Separately, and Giving their Distinctive Features and Most Salient Characteristics (Baltimore: Manufacturers’ Record Co, 1887), 37–8.

- James A. Beeby, Revolt of the Tar Heels: The North Carolina Populist Movement, 1890–1901 (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 15, 20–21.

- Illustrated Guide Book of The Western North Carolina Railroad (Salisbury, NC: Passenger Department of the Western North Carolina Railroad, 1882); Gordon B. McKinney, “Zeb Vance and the Construction of the Western North Carolina Railroad,” Appalachian Journal 29 (2001): 58–67; Stover, 145.

- Greensboro Patriot, September 3, 1891; “The Fatal Disaster on the Western N.C.,” Charlotte Chronicle, August 28, 1891; “They Are Censured,” Concord Weekly Standard, September 3, 1891.

- This testimony appears in full in “The Story of the Wreck.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- T. J. Stiles, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2002); “Is He The Wrecker?” Atlanta Constitution, March 23, 1895; William G. Thomas, Lawyering for the Railroad: Business, Law and Power in the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999), 120–124.

- “The Story of the Wreck.”

- A copy of this letter was reprinted in “The Narrative of the Wreck,” Statesville Landmark, September 10, 1891.

- “The Great Disaster,” Statesville Landmark, September 10, 1891; “One Man Dissented,” Asheville Citizen, September 12, 1891.

- “The Story of the Wreck”; “A Rail Was Removed,” Asheville Democrat, September 10, 1891.

- “The Great Disaster”; The reward ad ran multiple times in many papers. For an example see the Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1891; Letter from Pinion Detective Agency to Bennehan Cameron, September 13, 1891, Bennehan Cameron Papers, #3623, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Statesville Landmark, August 11, 1892; Homer Keever, “Bostian Bridge Train Wreck In 1891 Is Considered Controversial,” Statesville Landmark, August 25, 1966.

- William G. Thomas, Lawyering For the Railroad: Business, Law and Power in the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999), 80; Diary, December 17, 1894, David Schenck Papers, #652, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Letter from S. P. Read to Bennehan Cameron, August 31, 1891, Bennehan Cameron Papers, #3623, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 14; Edward L. Ayers, Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the 19th-Century South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 238–245.

- “That Terrible Wreck,” Progressive Farmer, September 1, 1891; “The Bostian Bridge Disaster,” Progressive Farmer, September 9, 1891; “A Diabolical Deed” Richmond Dispatch, August 29, 1891.

- Mark Aldrich, Death Rode the Rails: American Railroad Accidents and Safety, 1828–1965 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 43; Interstate Commerce Commission: Statistics of Railways in the United States (Washington, D.C., 1890), 80 (1891), 96 (1893), 74–75 (1894), 84–85 (1895), 93–94 (1896), 96–97 (1897), 94–95 (1898), 106–107 (1899), 107. The ICC defined “Deep South” as Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi and “Upper South” as South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.

- Hunt McCaleb, “A Ride on an Engine,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, April 24, 1892; This data is from a search of the online Atlanta Constitution for “train” and “wreck” in the 20-year period between January 1, 1878 and January 1, 1898. A train wrecking attempt could be something as innocent as a crosstie on a track or a misplaced rail, but as long as the paper suggested malicious intent or a deliberate effort to wreck a train, a case was tallied. The data set includes cases from 10 states (VA, NC, SC, GA, FL, AL, MS, TN, AR, LA); “Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery,” Raleigh News-Observer, July 7, 1898; “To Editor State Herald,” Birmingham State-Herald, December 30, 1896.