I am hopelessly bad at geography. I can hardly tell north from south and latitude from longitude, let alone try to name cities, states, and countries on a map. Nevertheless, the course I love teaching is “Treasure(d) Maps: Writing the American South,” designed in 2018 when the English Department at Duke University invited me to create a southern literature course. I recalled how my first introduction to southern literature in college was William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! (1936). What is most peculiar about the novel is how it curiously ends with a map in which Faulkner proclaims himself a “proprietor,” not an “author,” and reveals plot points to other unpublished novels by him. What does it mean to dub yourself a “proprietor”? Why inscribe a map with sentences and stories as opposed to location and place? Can a novel actually conclude if the final page is a map?

As these questions brewed and I designed a new course, I also prepared for my comprehensive exams in English. After reading hundreds of African American and Caribbean novels from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, I soon realized that Faulkner was hardly the first writer to manipulate maps. Moreover, many Black feminist writers today also devote significant attention to space, place, and race especially as it concerns the Black South. In 2020, I redesigned a version of “Treasure(d) Maps” at Fordham University—now titled “Treasure(d) Maps: Black Women, Southern Literature, and Cartography”—to pay homage to Black women literary geographers who are overlooked as such and who understand how maps can mark the difference between living and unliving in a deeply anti-Black world. In a moment beset by increasing migrations as a result of climate change, unequal voting due to gerrymandering, and threats against reproductive health, we need as many Black literary geographers as we can find to help us make a way out of these impossibly difficult times. Novelists and poets use their aesthetic creations to help stretch our imaginations and equip us with tools to best combat life-threatening circumstances.1

The anchor text for “Treasure(d) Maps” is Gloria Naylor’s third novel, Mama Day (1988), which follows the burgeoning relationship between George Andrews and Ophelia “Cocoa” Day, whose family hails from Willow Springs, a fictional barrier island off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina that belongs to neither state. Naylor was a novelist, essayist, and filmmaker, but she was also a Black literary geographer. Consider the titles of Naylor’s novels, which reveal a deep investment in place: Bailey’s Café (1992), Linden Hills (1985), The Women of Brewster Place (1982), and The Men of Brewster Place (1998). Her novel Mama Day pushes that interest in place further, beginning with a map that depicts Willow Springs, which is modeled off the Sea Islands and contains a story unto itself that stands apart and in relation to the narrative that unfolds upon it, a story that contests settler-colonial violence and demonstrates how to protect one’s home and values.

Naylor’s literary map, which is deeply informed by her travels to Mississippi, South Carolina, St. Helena Island, and Mexico, as well as interviews with Black women, centers what Black and anticolonial studies scholar Katherine McKittrick calls “black women’s geographies” or “their knowledges, negotiations, and experiences.” As literary scholar Randi Gill-Sadler argues, Naylor’s writing “contests Cold War approaches to knowledge production and geographies that seek to dispossess, collect, and contain bodies of land and bodies of knowledge.” Her writing belongs to a tradition of Black feminist literature that, as Erica R. Edwards describes, “call[s] forth new languages, new practices, and new imaginaries of survival and safety.” In so doing, Naylor’s map teaches students to loosen their grip on nationalism, consider how people and places exert influences on each other, and look for home in unexpected places. By meditating on Naylor’s anti-imperialistic cartographic practices in Mama Day, students explore what those cartographic practices make possible within the classroom when they make their own maps to account for their lives. I also want students to know that they do not have to resign to the world as it is given to them but can follow this bold and brilliant author’s example to recast the perimeters and parameters of where and what matters.2

A Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Willow Springs, or The Map and Its Maker

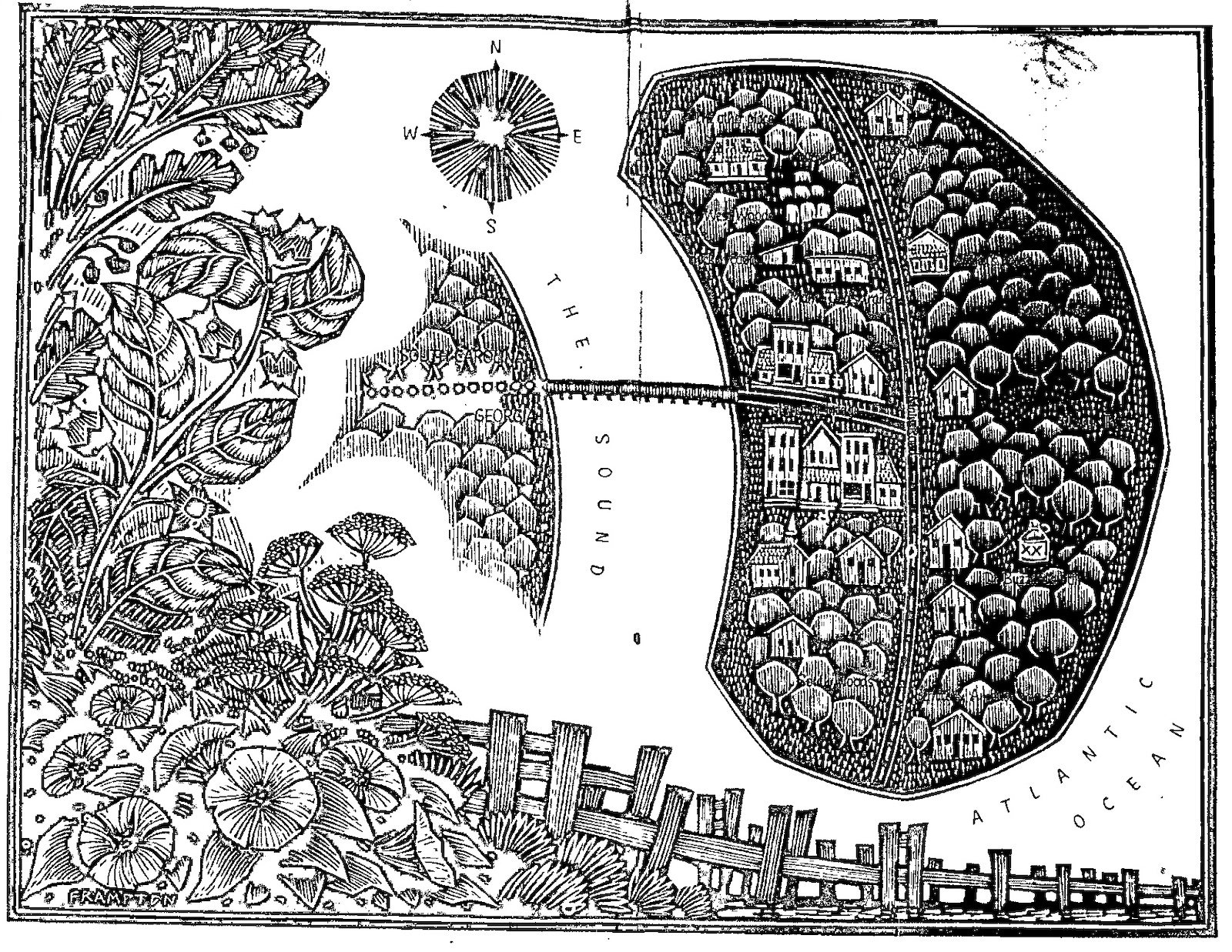

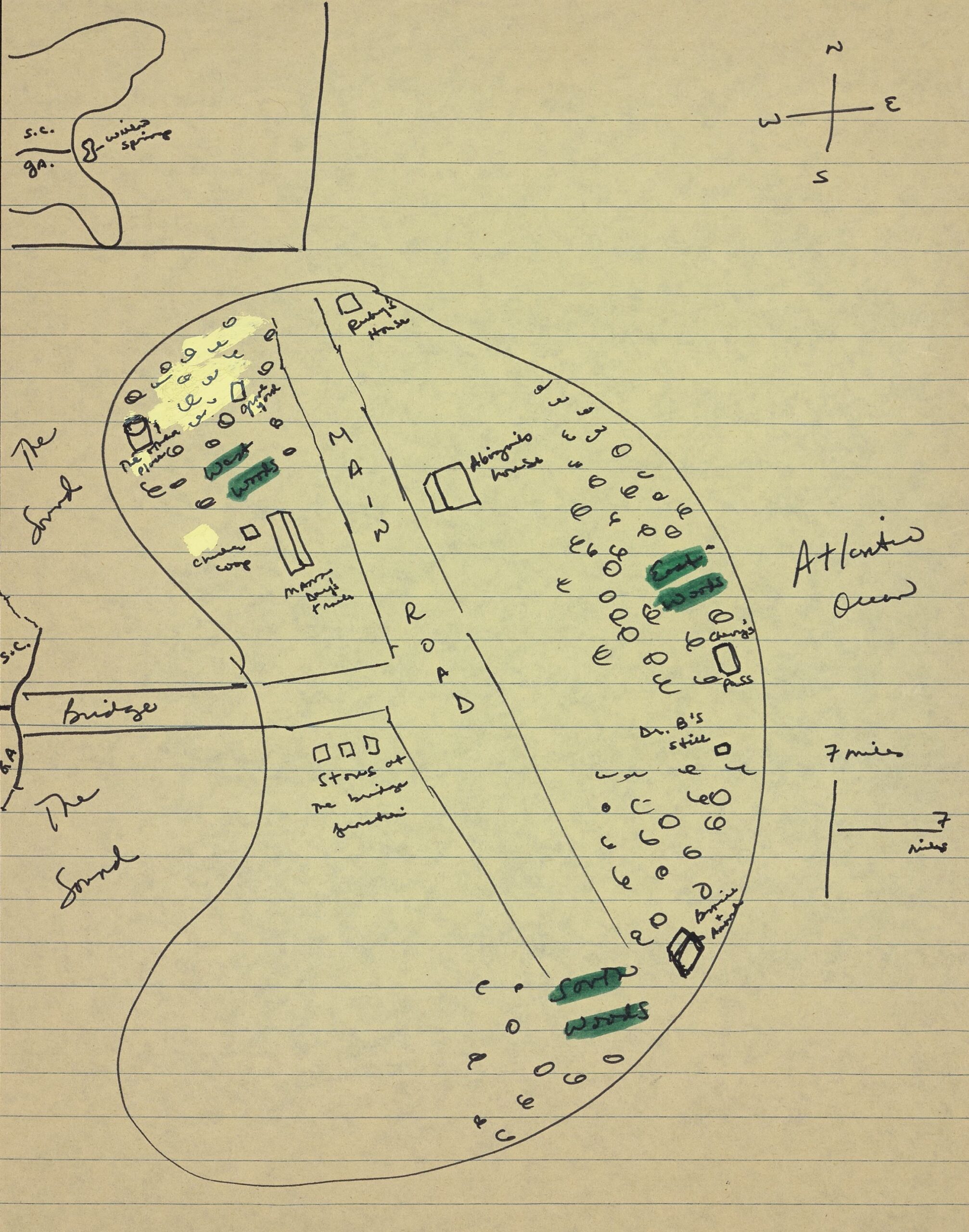

Mama Day begins with three different artifacts: a map that depicts Willow Springs in relation to the United States, a genealogy, and a condition of sale for an enslaved woman named Sapphira who was sold to Norwegian slave owner Bascombe Wade on August 3, 1819. Whereas readers might expect a narrative soon after the title page or a preface, we are presented with images. Naylor forces us to slow down. The images with which she opens her novel invite close looking, a thorough engagement with figures and artifacts that surround a novel in an effort to discover what stories they hide and reveal. Taken individually, each image at the start of Mama Day provides context for the story that follows: a map that covers the areas that the characters traverse, a genealogy of many of the important characters that will appear in the story, and a condition of sale that points to a known and unknown presence that haunts the story. Taken together, however, the artifacts raise larger questions about the nature of objective truth and who can lay claim to it. For instance, the created map prompts a question about who its maker might be and what they are trying to convey. The genealogy raises issues about practices of naming and knowing. And the condition of sale demonizes Sapphira—who, we know from the genealogy that precedes it, is the matriarch of the family that lives on Willow Springs—by attributing her cunningness to “extreme mischief and suspicions of delving in witchcraft.” Immediately, these three artifacts initiate a conversation not only about what constitutes truth but, importantly, how we even know that something is true.3

When asked in 1988 about why she created Willow Springs, Naylor responded, “I needed a landscape to demonstrate a state of mind or a metaphysical situation. So, I need a place that was a part of the United States but not quite part of it. I needed that, and the island was just perfect.” As Gill-Sadler explains, it was not uncommon for Black women writers in the 1970s and 1980s to set their fiction in the Caribbean or even travel there themselves: Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby (1981) takes place on the fictional island of Dominque; Paule Marshall often used her grant money to travel to Barbados and write her novels; Audre Lorde spent time in Grenada after the US military invasion in 1983 and lived out her final days in St. Croix; and June Jordan detailed her vacation to the Bahamas in an essay. To better understand Naylor’s impulse to flee from the United States and create an island modeled on the Sea Islands, one need only consider the conditions she lived through in the United States during the mid- to late twentieth century. Naylor grew up reading newspapers that documented the Cold War. During this period, she said: “See, we felt like the Russians were coming. What people don’t realize is that about every thirty years we get a red scare and the Russians start coming again.” Naylor came of age in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and became politically conscious during the Black Power Movement. While some of her contemporaries enlisted in the Black Panther Party or became antiwar hippies, she joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses. For seven years, Naylor was a missionary in North Carolina and Florida proclaiming the arrival of a theocratic government. But in 1975, when the theocratic government she proclaimed failed to arrive, a disenchanted Naylor left the organization and returned to New York. She later enrolled in school and committed herself to writing. Language became her refuge, words her sanctuary.4

However, as Naylor’s fiction indicates, she not only relied on words but also on elaborate images. Sprawled across two pages, a tenuous bridge—referred to in the novel as “strong enough to last till the next big wind”—connects South Carolina and Georgia with Willow Springs. That Naylor includes only South Carolina and Georgia from the United States and places them in the center of the map, even though New York City is a prominent location in the story, suggests a major reorientation that emphasizes the centrality of the Black South in the story. It also prompts a reconsideration of Black southern remigration and challenges narratives that presume Black people could only archive freedom in the north. The bridge that connects South Carolina and Georgia to Willow Springs establishes not only a geographical connection but also a relation that suggests one of influence. Rather than depicting street names or avenues, the map presents us with specific homes, such as Ruby’s House, Abigail’s House, Mama Day’s Trailer, and Bernice and Ambush’s House, as well as important locales, including The Other Place, the Graveyard, and East Woods and West Woods. The meticulous attention to people and communities and how they exist in relation to one another implicitly suggests that, in Willow Springs, people know one another and matter to each other. Finally, the untamed natural world that frames the left side of the map is suddenly transformed into a fence along the bottom of the map. Together, the flora and fence act as borders for the map, inviting readers to ask: How do mapmakers accurately represent a place if they have to draw limits and leave things out? Is it ever possible to fully represent a place? These sorts of questions recall Black feminist theorist Imani Perry’s meditations on cartography. She writes about “Bonini’s Paradox,” which refers to the idea that “a map that includes everything is unusable, and yet a map that doesn’t include everything is to some extent inaccurate.” Perry’s reflections coupled with the different borders on the map emphasize the artifact’s constructed nature and warn against accepting it as a complete representation.5

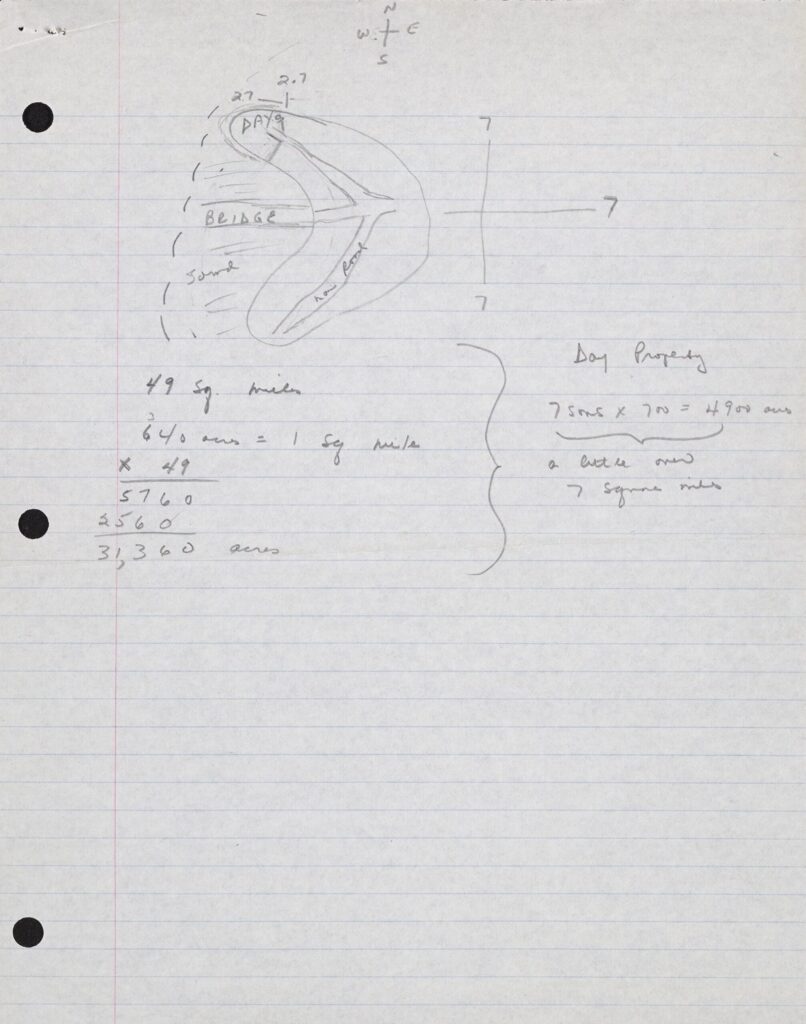

Naylor consulted many different kinds of maps as she constructed the one in Mama Day. The Gloria Naylor Archive is currently housed at Lehigh University, where faculty, staff, and researchers have digitized some of her work. The archival materials for Mama Day are extensive. Apart from articles Naylor read about different medicinal herbs and research conducted on hoodoo and voudou, the archive contains a plethora of maps. Some of the maps, including one of the New York City subway and Staten Island, reflect the area George hails from in the novel. Other maps point to states and cities in the South. Naylor collected and studied maps, travel pamphlets, and guidebooks from the South and visited some of the places represented in these documents. She conducted in-depth research on South Carolina, and her papers include a guidebook for Low County Charleston, maps and pamphlets for Anson-borough and East Cooper, various maps of North and South Carolina, and information about Boone Hall Plantation and Garden. There is even a form from the United States Department of Interior, from which Naylor could order geological and topographical maps of South Carolina.6

Naylor also devoted substantial research to the Sea Islands. Her archives include several brochures on Beaufort, South Carolina, and the Gullah Fresh Air Market; pamphlets about Hilton Head and Fripp Island; and an advertisement for Daufuskie Island. Many of the materials on the Sea Islands address how to preserve the culture of particular communities as outside development seeks to intervene, which informs the preamble that introduces Willow Springs in Mama Day. In this eight-page overture, the narrator describes some of the challenges Willow Springs faces: “Malaria. Union soldiers. Sandy soil. Two big depressions. Hurricanes” and what ultimately threatens to upend it all: “ . . . new real estate developments who think we gonna sell our shore land just because we ain’t fool enough to live there.” These developers, the narrator explains, “started coming over here in the early ’90s talking ‘vacation paradise,’ talking ‘picturesque.’” However, the people who belong to Willow Springs have no intention of selling or leaving. They know very well what happens when developers intrude: “Hadn’t we seen it happen back in the ’80s on St. Helena, Daufuskie, and St. Johns? And before that in the ’60s on Hilton Head? Got them folks’ land, built fences around it first thing, and then brought in all the builders and high-paid managers from mainside—ain’t nobody on them islands benefited.” Fully aware of ecological, financial, and manmade dangers that hover over the Sea Islands, Naylor created Willow Springs intent on preserving culture rather than selling out, embracing its southern heritage rather than apologizing for it. Indeed, when Naylor’s archival sources are considered alongside the opening paragraphs of Mama Day, it reads as a warning against capitalist impulses that are prone to invade and destroy southern geographies.7

One document buried among the research files for Mama Day is titled “Maps, genealogies, and notes.” In this file, Naylor sketches possible outlines of Willow Springs. In addition to her focus on people by using specific homes and landmarks, there is also a concern with spatial dimensions. Several images show intricate measurements and calculations indicating that she imagined the island as seven miles in length and width, and marginal comments describe how much land the ancestors of Willow Springs have. What these “Black mathematics” reveal is an interest in how Black people, especially those in the South, take up space and make their presence known. For a people invisible to the mainland, the map announces their presence and personhood, their practice and participation in the world.8

The Women Behind Willow Springs: Eva, Hester, and Ruth

Naylor not only collected and studied travel pamphlets, brochures, and maps; she also visited some of these places, as evidenced by travel receipts in her archives. When asked about research she conducted for Mama Day, she said, “I traveled back to Robinsonville, Mississippi, to talk to an old woman who was a midwife and healer for the town. I went to Charleston and the Sea Islands off the coast to talk to the people there about individuals who had worked with roots and herbs. I read several books on herbal healing, psychic healing, natural and supernatural phenomena.” Naylor’s papers include a seventy-nine-page interview with Eva McKinney, a Black woman in her eighties, who was her grandmother’s best friend (and the midwife and healer mentioned above). McKinney was born in Macon, Mississippi, and spent much of her life in Robinsonville, Mississippi. In their conversation, McKinney and Naylor cover a range of topics, from the uses of medicinal herbs and midwifery to hard work, family obligation, and kinship ties. As a companion to older people in Mississippi, McKinney learned to support herself and those in her community. “The master said that every weed that He created on the ground would cure any kind of complaint that the human have,” she told Naylor. “But now the thing about it is knowingwhat weed it is. And knowing what to do.” McKinney’s desire to truly understand how things work made her a healer for her community, like the women in Mama Day, such as Miranda, who provide more treatment than the doctor in Willow Springs, Dr. Buzzard. Like McKinney, who used her knowledge to help those around her, Miranda wields her magic to aid her neighbors, notably Bernice and Ambush, who try to get pregnant, and uses her powers in direct opposition to Dr. Buzzard, who uses his medical knowledge to harm those around him and practice Black magic.9

Prior to the publication of Mama Day, Naylor wrote an article for Essence magazine titled “Until Death Do Us Part,” featuring two Black southern sharecroppers, Hester Hall and Ruth Scott, also from Robinsonville, Mississippi, who supported their community until the end of their lives. Their sixty-year-old friendship, Naylor reveals, began in Greenwood, Mississippi. Hester, who was married without children, ran a café in Greenwood, and Ruth returned to Green-wood to farm with her husband. When he died, Ruth moved to Robinsonville, but her friendship with Hester never waned during their years apart, and when Hester became ill, she moved in with Ruth. Naylor’s article explores the care they provided to their town and to each other. Whereas we often associate the phrase “until death do us part” with marriage, Naylor redeploys it in this context to show how these two Black women shared a deep commitment to one another outside the institution of marriage. They may not have had much, but they pooled their food stamps and pension funds, and they had each other. When Hester moved in, Ruth said: “She can stay here with me long as she wants to. If I eat, she gonna eat; if I sleep, she gonna sleep. If I ain’t got nothing but a cotton house, she got a corner.” Naylor concludes: “In their final years they have found something more than survival. Each can watch the sun set on a day that has provided a reason for living it.” In each other, they found a home.10

Not unlike how Eva McKinney influenced the creation of Miranda and her healing capacities in Mama Day, there are strong parallels between Ruth and Hester’s relationship and that of Miranda and her sister Abigail in the novel. Like Ruth and Hester, Miranda and Abigail care for each other and their community because they know the land. They’ve worked on it and worked it. Each knows what the other wants. Recall how Miranda once tells Ambush, “You know what an old collector I am,” as she walks into the woods to retrieve medicinal herbs, or how Abigail frequently greets Miranda by saying, “You there, Sister?” The question reinforces Miranda’s presence and indicates that Abigail, too, is always beside her. When each of their husbands die, they become one another’s keepers. Together, Eva, Ruth, and Hester introduce Naylor to a different kind of knowing, initiate her into a different process of learning. This kind of knowledge, as they each teach her, can guide one’s living and life. From them, Naylor learns that the Black South is not just a series of places, but a set of practices informed by Black southern women, placemakers who know the curvature of the earth and how it can help save those who walk on it. Their “Black women geographies” helped Naylor create Willow Springs. She not only listened to them; she honored their spirit and their lives in her work.11

Teaching Mama Day, Mapping with Naylor

As George and Cocoa fall in love in Mama Day, my students fall in love with them, but the novel is not without controversy in the classroom. We do not always have words for what happens in Willow Springs. Like Reema’s boy, who returns from college to “study” Willow Springs using his training as a cultural anthropologist, the analytical tools at our disposal cannot prepare us for the intricate information passed on and between Black women. Like George, who goes to the library to find books on love to prepare for his relationship with Cocoa, no number of books about the Sea Islands will prepare us for Willow Springs. At least once each semester, a student remarks that Willow Springs does not operate rationally, and I push back: What constitutes rationality? And how we can make such a claim when an entire island is said to have followed the rules created by them? This typically leads to a larger conversation about objectivity and truth, or how we know what we know. In the end, we always return to the first several images presented in the book—the map, the genealogy, and the condition of sale—which reminds us that knowledge, like the map, is constructed.

The final project for the course is inspired in part by the map in Mama Day. I invite students to make a map that represents one portion of their life that shapes who they are. For a brief period of time, they become cartographers equipped with powerful maps made by the Black feminist geographers studied in the course. Students can make a map in whatever form they deem appropriate. Perhaps it is a prose-poem like Dionne Brand’s “Ruttier for the Marooned of the Diaspora” or a short memoir narrative like Sarah M. Broom’s meditations on New Orleans East. They can design a map like Naylor or pay homage to a person of influence like Alice Walker did for Zora Neale Hurston in her articles. Students are not graded on creativity but for their artist statement, which explains the contents of the map, editorial decisions, and reflections on what was impossible to render. They also infuse the artist statement with words by Black feminist literary geographers. On the final day of class, students share their work with one another, and the results are spectacular.

The first year I assigned this project at Fordham, I taught online. Students tuned in from their homes or dorm rooms in their respective countries, which gave them greater access to family and personal memorabilia to consult or include in their final projects. One student, Mithraw, was so moved by how Naylor’s Mama Day honors family matriarchs that he created a family photograph album in tribute to the women in his life who traveled from Sri Lanka to the United States to make a life for him, then gifted the final project to his grandmother. Another student, Joseph, wrote a series of poems about his time in Louisiana and Oklahoma that inspired his decision to enter the Society of Jesus. And another student, Sophia, who traveled to the Bronx with the Q44 bus for high school and college, superimposed an MTA bus map with her own created map pointing out sites of importance that captured growing up on this particular route. Each of these projects and many not referenced here showed how both people and places contributed to the formation of each student. As they shared these projects with their classmates, they realized they were someone else’s students first and that the classroom is but one place where learning occurs.

When we expand the framework to consider Naylor as literary geographer and cultural producer, we open ourselves to the opportunity to learn how to reside in and with places differently. Like the residents of Willow Springs, we recognize that knowing one’s neighbor is as significant as knowing street names. Teaching Naylor’s novel with an eye toward how she situates the Black South decenters stories that privilege the North as the primary locale of importance. In placing the Black South center stage and honoring Black women and their foremothers, Naylor returns readers to their roots. Or, like my student Paul said the first time I taught Mama Day, “Naylor taught me that we don’t need a new map. We need a new world.”

This essay was published in the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 2: Summer 2023).

Sasha Ann Panaram is an assistant professor of English at Fordham University, where she specializes in African American and Caribbean literature. Her research has been published or is forthcoming in The Black Scholar and Small Axe. Her public-facing scholarship appears in Public Books, Black Perspectives, the Brooklyn Rail, and elsewhere.

NOTES

- See Sarah M. Broom, The Yellow House (New York: Grove Press, 2019); Ntozake Shange, A Daughter’s Geography (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983); Paule Marshall, Triangular Road (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2009); and Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001).

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), x; Randi Gill-Sadler, “Conjuring Cartography: Black PlaceMaking in the Cold War in Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day,” Electric Marronage, February 27, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/ElectricMarronage/videos/electric-marronage-randi-gill-sadler-public-talk/138094920787671/; Erica R. Edwards, The Other Side of Terror (New York University Press, 2021), 14.

- Gloria Naylor, Mama Day (New York: Random House, 1988), 3.

- “An Interview with Gloria Naylor,” in Conversations with Gloria Naylor, ed. Maxine Lavon Montgomery (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2004), 58–59. Gill-Sadler explains how Black women writers used fictional and literal islands to critique US imperial militarization. See “Conjuring Cartography.” Kay Bonetti, “An Interview with Gloria Naylor,” in Conversations with Gloria Naylor, 40.

- Imani Perry, Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 179.

- Mama Day—questionnaire, undated Box 20, Folder 7, Gloria Naylor Archive, Sacred Heart University.

- Mama Day, 4, 6.

- When I use the phrase “Black mathematics,” I am thinking of McKittrick’s article “Mathematics Black Life” and her phrase “the mathematics of unliving” that refers to how “breathless, archival numerical evidence puts pressure on our present system of knowledge by affirming the knowable (black objecthood) and disguising the untold (black human being).” Naylor’s “Black mathematics” works differently, not subjecting Black people to lists and numbers but rather pointing to how Black life proliferates and asserts itself against systems of domination. The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (2014): 16–28. Recall, in the discussion of the hurricane that visits Willow Springs, how those on the island say, “It’s like we don’t exist for them . . . ” Mama Day, 249.

- Her papers contain travel receipts for Boone Hall Plantation, an Amtrak ticket from Georgia to Penn Station, a plane ticket to Miami, and other museum and travel receipts. Mama Day—questionnaire, undated, Box 20, Folder 7, Gloria Naylor Archive, Sacred Heart University. Interviews with Eva McKinney, undated, Box 20, Folder 19, Gloria Naylor Archive, Sacred Heart University.

- Gloria Naylor, “Until Death Do Us Part,” Essence 16 (May 1985): 133.

- Mama Day, 78.