“‘A mother and a little boy were walking along, and I could tell the minute the recognition hit the little boy,’ Nabors told the LA Times. ‘As he walked by holding his mother’s hand, he said in a real loud voice, ‘Look, Mother. There goes an old Gomer Pyle!'”

Walking through Chicago’s O’Hare airport, Jim Nabors, star of the enormously popular 1960s sitcom Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C, encountered a look that summed up his life. “A mother and a little boy were walking along, and I could tell the minute the recognition hit the little boy,” Nabors told the LA Times. “As he walked by holding his mother’s hand, he said in a real loud voice, ‘Look, Mother. There goes an old Gomer Pyle!’”1

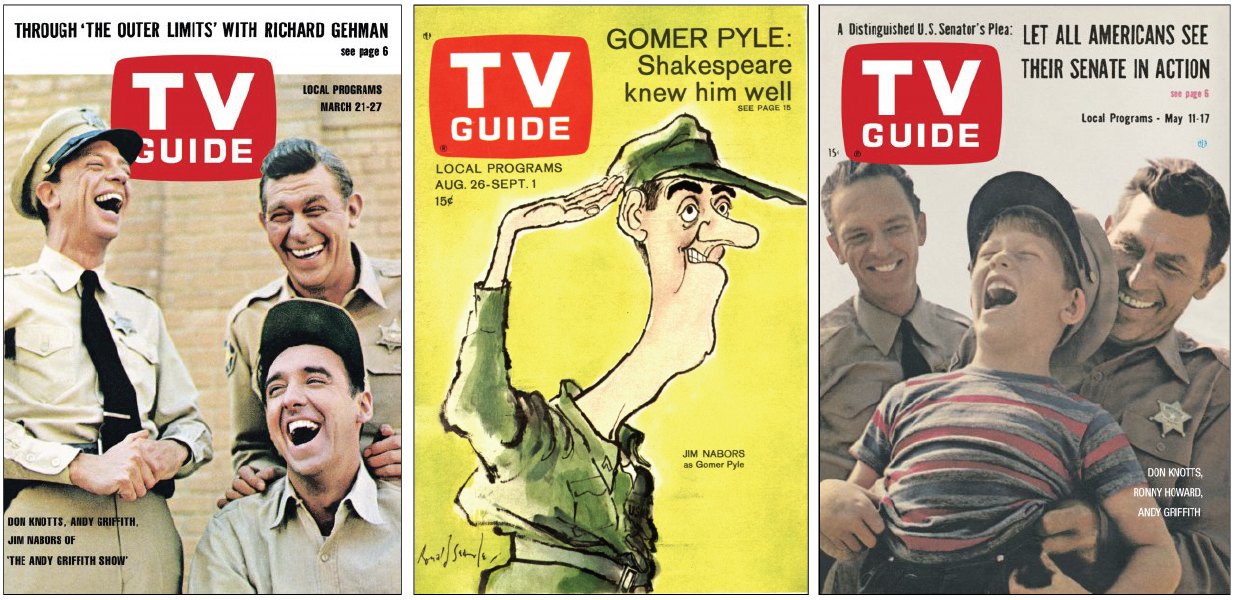

It’s common that actors are known not by their real names, but by the characters they play. This was particularly true during the 1950s and 1960s, when stars of rural sitcoms purposely blurred the line between their characters and real selves. Producers, and occasionally actors, believed that one of the key reasons people enjoyed rural sitcoms was because they seemed realistic. As a result, performers on programs such as The Real McCoys, The Andy Griffith Show, and The Beverly Hillbillies often adopted aspects of their roles—usually naïve southern hicks—as part of their public personas, careful not to act like movie stars and destroy the illusion.

An examination of contemporary periodicals from the era indicates that journalists were partially responsible for promoting false realities, as they frequently drew comparisons between actors and the characters they portrayed— especially southern actors playing southern parts. Usually appearing in national publications, such articles led the public to believe that rural sitcom actors were just ordinary people who exaggerated their quirks for the camera. This aided in perpetuating derogatory stereotypes about the white South, since many readers and audience members had no other frame of reference.

Since the creation of movies and radio, producers have hired actors in the South and beyond to play certain parts, creating and maintaining a public image for them based on that typecasting. For instance, studios helped one of Hollywood’s first movie stars, Mary Pickford, protect her image as “America’s Sweetheart” well into her forties, in spite of a nasty divorce, a hasty subsequent re-marriage, and her role as an entrepreneur who aided in the creation of a powerful film production company. Similarly, studios portrayed John Wayne as a patriotic figure beyond his role in several heroic war movies in the 1940s, even though he actively avoided military service during World War II. In the age of television, actors often made public appearances dressed in costume or maintained aspects of their stage persona while in the public eye. After all, the studios and networks had a stake in making sure their stars connected with the public on a personal level. The stronger the emotional attachment a viewer developed for an actor, the more likely the viewer would spend money at the theater to see the actor’s movies. Television producers had no reason to believe the same rule did not apply to their audiences.2

Blurring the line between the actor and character helped create a sense of realism in the absurdist world of rural comedy—a world that many viewers were happy to accept as true.

When rural comedy came along, the characters remained white— there were virtually no black faces on network television until the mid-1960s— but were different in voice, language, dress, and custom, requiring many viewers to suspend the reality they knew. For example, it took more to make viewers think that Granny Clampett was building a fire in the stove or chasing a kangaroo through the yard on The Beverly Hillbillies than it took to make them believe that Dennis Mitchell had annoyed his neighbor on Dennis the Menace, or that Laura Petrie was vacuuming the rug on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Blurring the line between the actor and character helped create a sense of realism in the absurdist world of rural comedy—a world that many viewers were happy to accept as true.

According to historian Karen Cox, industrialization near the turn of the twentieth century left Americans nostalgic for simpler times. And to many people, the South seemed to best represent what America was like before widespread urbanization. It was an exotic, yet uniquely American location that demonstrated the nation had not completely forsaken its pastoral heritage. This in part explains why continuity and realism were considered integral to the success of rural comedies. An actor behaving like a wealthy celebrity while promoting his show was tantamount to admitting that the program was fake, and by extension, that the comforting and familiar version of the white South it portrayed no longer existed.3

Promoting “the cotton pickin’ song and dance man”

In their reviews of rural comedies, entertainment writers for national publications like TV Guide, Newsweek, and The Saturday Evening Post drew from a large collection of negative white southern stereotypes. These ideas also existed in American media during the nineteenth century. But as historian Jack Temple Kirby argues, they gained prominence during the first half of the twentieth century, when southern artists began to capitalize on characteristics from the region. For instance, Margaret Bourke-White’s Depression-era photographs emphasized southern poverty, as did Erskine Caldwell’s novels, particularly Tobacco Road, though his work was more depraved and somewhat exploitative. Tennessee Williams’s plays brought southern eccentricity to a new audience through vulnerable and neurotic characters like Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire and Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie. And many works introduced the notion of the southern hillbilly, a character historian J. W. Williamson argues began as a means of self-affirmation for hill people, but eventually became an instrument to mock and diminish poor, rural whites. Though portrayals of hillbillies ranged from evil and depraved to clownish, audiences found humorous characterizations most engaging, making the affable southern fool an established fixture in popular culture—from the Lil Abner and Snuffy Smith serial cartoons to Red Skelton’s clownish radio and television character Clem Kadiddlehopper to the silly Ma and Pa Kettle movies of the 1940s and 1950s.4

When the rural television craze developed in the late 1950s, reporters used existing white stereotypes to draw connections between characters and actors, helping make the stories about the performer’s accent, funny aphorisms, impoverished relatives, and rural hometown instead of about their career and accomplishments. Country singer Tennessee Ernie Ford was among the first southern performers to experience such treatment. In 1957, after several successful appearances as Lucy Ricardo’s mountain-dwelling cousin on I Love Lucy, Ford got his own musical variety show on NBC. Though he was a classically trained musician who studied voice at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, Ford’s penchant for country music, southern accent, and rural upbringing seemingly made those facts irrelevant. Reporters noted how similar he was to the naïve hillbilly characters that he often played, advertising him as a “cotton pickin’ song and dance man” and a “natural” yokel doing the only thing he knew how.5

I’m nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs!

An article titled “Tall Hawg at the Trough!” focused on Ford’s speech, including sayings like, “I’m nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs!” Bob Thomas created “The Sayings of a Pea Picker,” an entire column in the Saturday Evening Post that was essentially a list of Ford’s most popular aphorisms. In one entry, Thomas published an imagined interview between Tennessee Ernie and Tennessee Williams, pitting an ignorant bumpkin against an urbane wit. When, for instance, Tennessee Ernie asks of Tennessee Williams’s writing career, he replies, “Oh, one of them writin’ fellars! What do you write, the farm news or the sportin’ news?” Like Thomas, many writers in the 1950s and 1960s used phonetics to capture the dialect of rural actors—a method that was considered racist, and thus was rarely used, when quoting other ethnic minorities. Though intended to add “color” to articles, the use of phonetics led to a diminished view of southern intelligence and propagated the notion that white southerners were, in the words of John Shelton Reed, “the last acceptable ethnic fools.”6

When non-southern actors played southern or rural characters, news features typically highlighted how the two were not alike. For example, in the late 1950s, a series of westerns—The Gray Ghost, The Rebel, and Sugarfoot— all featured a non-southern actor as a former Confederate soldier. In a TV Guide profile of the leads, the reporter took pains to differentiate the men from their characters, going as far to mention two of three actors’ home state or town in the title. Quite different from southern focused features, none of the articles phoneticized speech in an attempt to capture their dialect.7

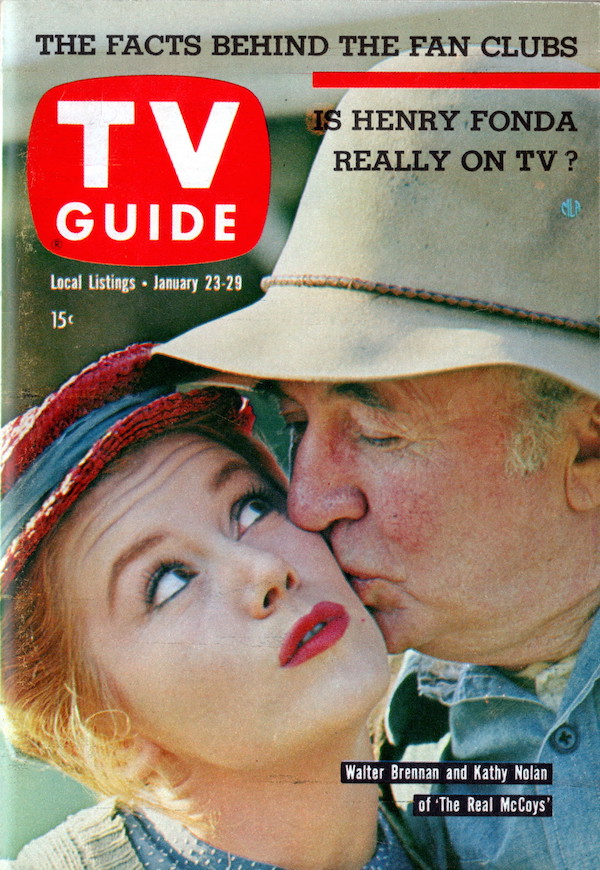

Actors in The Real McCoys, generally considered the first rural situation comedy, were treated differently in print depending on where they were from. An ABC series that aired from 1957 to 1963, The Real McCoys followed a grandfather and his grandchildren as they moved from their mountain home in West Virginia to a farm in California that a relative had left them. In a TV Guide profile of Kathy Nolan, who played the wife of the eldest McCoy grandson on the show, the reporter emphasized that she had spent her childhood on a showboat travelling all over the South. In contrast, articles about Walter Brennan, who starred as the crotchety hillbilly grandfather Amos McCoy, often mentioned his Boston heritage, insisting that he was nothing like his character. Some magazines even reported that in real life, Brennan more closely resembled a Boston banker than a West Virginia farmer. But Brennan worked to stay in character for the public. He often gave interviews as Amos and had an advice column in which he frequently drew comparisons between himself and the fictional McCoy. He posed for photographs in costume— a pair of overalls, an open-necked denim shirt, and a floppy brimmed hat— and claimed that he closely resembled his character in real life, even noting that he had won three Oscars just for playing himself. ABC, for its part, did nothing to discourage the deceit.8

Producer Paul Henning encouraged a similar approach with the cast of his show, The Beverly Hillbillies, which aired on CBS from 1962 to 1971. With the exception of Donna Douglas, who played Ellie May Clampett, none of his four leads was natively rural or southern. Henning worried that his cast’s lack of southern roots would hurt the show’s popularity. He also thought that magazine layouts of Buddy Ebsen (who played patriarch Jed Clampett) on his yacht or Max Baer Jr. (who played Jethro) going to a nightclub would break character continuity, so he created a news blackout of the actors’ private lives. In a June 1962 memo to his production staff, Henning wrote:

I would prefer that Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer cease to exist as themselves. The dissemination of personal biographies and so-called squibs, blurbs, plants in columns and photo layouts of them at home are to be discouraged by every means at our disposal! A wrong story is one that damages the tv [sic] image of our hillbilly characters.

None of the actors could appear on a talk show except in character, and they were only allowed to discuss previous roles that contributed to the illusion that each person was playing himself or herself on the show.9

I would prefer that Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer cease to exist as themselves. The dissemination of personal biographies and so-called squibs, blurbs, plants in columns and photo layouts of them at home are to be discouraged by every means at our disposal!

Donna Douglas received the most press because she was the only one actually from the South. TV Guide reporters jumped on her Louisiana upbringing, claiming, “although not a true hillbilly, she is a native of the backwoods bayous of Louisiana, which except for the elevation, amounts to the same thing.” Such statements ignored the fact that Douglas grew up in the state’s capitol, Baton Rouge, and instead promoted a general southern stereotype. In a photo spread that appeared in TV Guide and documented a trip Douglas took to Japan, the reporter mentioned that she could not pronounce some of her handlers’ Japanese names, and thus she resorted to calling them “Mr. Click-Click,” “Mr. Whistle,” and so forth. These stories may have endeared Douglas to readers and viewers, but they also promoted the idea that she was merely playing a version of herself on television: a sweet, pretty, southern girl who wasn’t big on brains. Douglas at least was able to use this notion to her advantage. Along with Irene Ryan and Max Baer, she created a summer road show following the first season of The Beverly Hillbillies. Essentially a live version of the show, it featured Granny spouting of one-liners in costume to Ellie May and Jethro and became the highest grossing state fair act of 1963.10

Tightly controlled publicity was great for the show and the degree to which viewers engaged with it. In fact, viewers believed the show’s premise so much that when a magazine published the address of the mansion used in the series’ opening credits, tourists promptly besieged the family who lived there, hoping to get a glimpse of the Clampetts. According to occupants of the home, tourists believed the Clampetts were actual people, not just television characters. The incident forced producers to photograph a different mansion for subsequent episodes in an effort to restore the family’s privacy. Though the event created an enormous hassle for both the production team and the family who lived in the house, it spoke favorably about viewers’ emotional connection with The Beverly Hillbillies. Henning only increased the show’s believability when he created two other shows, Petticoat Junction and Green Acres. Both took place in and around Hooterville, the same fictional area of rural Missouri that the Clampetts allegedly left for Beverly Hills. Stars from all three shows took turns making guest appearances on the other programs during the five years that they ran concurrently, and the overlap created a plausible universe in which the characters lived side by side and popped in on old friends.11

For this kind of money, and this kind of fun, hell no!

The actors’ agreement to stay in character was also good for show business. When a Newsweek reporter asked Ryan, who played Granny on The Beverly Hillbillies, if she minded being typecast following The Beverly Hillbillies, she quickly replied, “for this kind of money, and this kind of fun, hell no!” But not all of the show’s actors were so flippant. Tensions rose as the actors became synonymous with the Clampetts, and the industry began to believe they were merely playing versions of themselves. Ebsen was an established character actor who could point to decades of previous work when looking for other roles, and Ryan was near the end of her career, but younger cast members faced limited opportunities in the face of typecasting and diminished perceptions of their acting abilities. Baer expressed frustration with the situation in one interview, saying that he hated being referred to in his real life as “Jethro,” and asserting that he was “no more like Jethro than the man in the moon.” Before The Beverly Hillbillies, neither he nor Douglas had substantial acting experience, and after the show ended in 1971, the degree of association with the show was so strong that neither of them was able to find much work and their careers foundered. Forty years later, Douglas continues to make occasional celebrity appearances based on her role as Ellie May Clampett.12

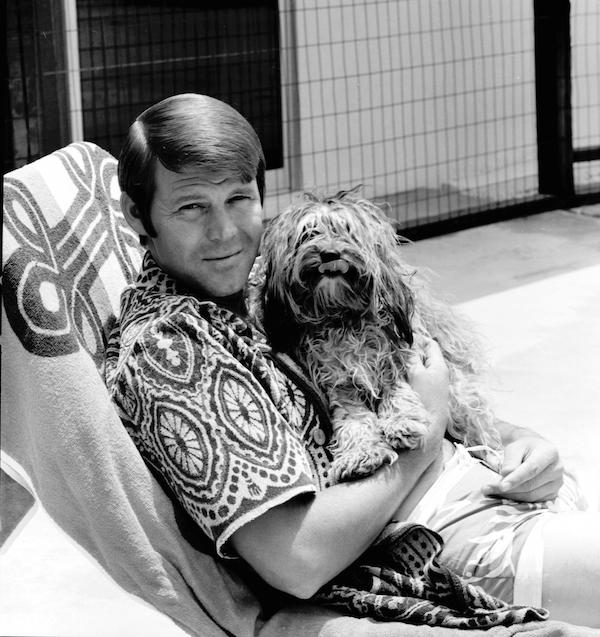

A strong association between performer and character did not always result in negative consequences for the actor. Glen Campbell, for instance, parlayed his regional affiliation into a successful career. Raised in a small town in rural Arkansas, Campbell was a sought-after session musician who toured with The Beach Boys before taking a job as a musician on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. On set, the Smothers often made fun of his rural background and accent. For instance, in the original script from November 3, 1968, Tom Smothers playfully cuffed Campbell and took credit for teaching him how to “talk good” (the joke was removed from the final broadcast). But later in 1968, the brothers and CBS chose him to host their summer counterpart, The Summer Brothers Smothers Show, knowing his southern roots and “aw, shucks” personality appealed to rural and southern audiences, as well as the elderly— demographics that were often turned of by the envelope-pushing humor of the Brothers. Campbell followed his hosting stint on The Summer Brothers Smothers Show with his own country-pop variety show, The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, and a part in the John Wayne feature film True Grit.13

A strong association between performer and character did not always result in negative consequences for the actor. Glen Campbell, for instance, parlayed his regional affiliation into a successful career.

But trading on his southern image came at a personal price for Campbell. His background was rarely mentioned in the few national articles written about him when he was a little known musician, but after he achieved some measure of fame in the summer of 1968, industry profiles tended to focus on his rural upbringing and southern accent. An article published right after Campbell started hosting The Summer Brothers Smothers Show included stories about impoverished relatives like Auntie Boe and his childhood spent bathing in creeks and slopping hogs. To highlight Campbell’s accents, reporters often used “Ah” for “I” and “mah” in place of “my.”14

He didn’t have a single hayseed on his cowboy boots.

Even when reporters did not use phonetics and allowed that Campbell was a competent and assured businessman, allusions to his rural southern roots still prevailed. In one profile from the late 1960s, entertainment writer Digby Diehl remarked that when he met Campbell, he “didn’t have a single hayseed on his cowboy boots”—a comment that made known he thought Campbell was outside of his “natural” environment. According to Diehl, Campbell looked every inch the confident Hollywood hotshot— that is, until he opened his mouth to speak. In that way, Diehl said he had trouble reconciling Campbell’s professional authority with his accent. Constant reminders of his southern roots may have charmed readers, but they also undermined Campbell, making him seem out of place in the entertainment industry. The image Campbell fostered, as well as the image that was created for him, was at striking odds with his true American rags-to-riches story. After spending some time with Campbell for a Family Weekly article, writer Gloria Paternostio acknowledged that most stories about him were condescending and did not acknowledge his versatility and talent as a performer.15

Mayberry Men

One of the better known actors to blur the line between fiction and reality was Andy Griffith, who made an entire career out of playing versions of the same character: a happy-go-lucky, naïve hick. The North Carolina native became famous in 1954 after his stand-up routine, “What it Was, Was Football,” became a national sensation. In the skit, Griffith played an ignorant bystander attempting to explain the strange goings on at what turned out to be a football game, all the while exaggerating his southern accent, using colloquial speech and local aphorisms, and relying heavily on a wide, toothy open-mouthed smile that more than one reviewer deemed his “hominy grits grin.”16

On the heels of his comedy success, Griffith took a role as country bumpkin Private Will Stockdale in the teleplay No Time for Sergeants, which aired on The US Steel Hour in 1954. He later reprised the role on Broadway and in a motion picture released in 1958. Those performances, as well as his part in A Face in the Crowd, received positive reviews, but the public believed Griffith was just being himself, not acting. While promoting the film, Griffith made clear that he did not want to pursue serious dramatic acting following his emotionally wrenching experience playing a southern demagogue in A Face in the Crowd, a decision that only added to that perception. The film’s publicity department attributed Griffith’s decision to the fact that working with artistic masters such as director Elia Kazan had overwhelmed “the barefoot boy from out yonder.” Kazan was credited for “wrenching” the performance from Griffith by relentlessly mocking his southern roots on set and calling him white trash. Because Griffith was so closely identified with his yokel persona, executives in the movie business assumed that making “real” movies was too difficult for him and that he could not aspire to method acting or artistry.17

Griffith continued to propel his hick persona, particularly after October 1960, when he became the star of Sheldon Leonard’s The Andy Griffith Show on CBS. The network did not force Griffith to stay in character, but he believed that his success and that of the show depended on a genuine appearance. Thus, he never broke character in public and took on television and film roles that embellished his country boy persona. During interviews, Griffith thickened his accent when it suited his purposes, something Sheldon Leonard confirmed when recalling their first meeting.18

Magazine articles often referred to Griffith as “the real L’il Abner” and consistently pointed out his lack of sophistication, though he held a degree in music from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and was an adept actor and comic. One particularly condescending article in The Saturday Evening Post quoted producer and actor Danny Thomas, who deemed Griffith a hillbilly, albeit one slightly re-shaped by show business. Donald Freeman, the article’s author, marveled that Griffith knew about room service, foreign foods, wine, and manners, though he retained “the strong residue of backwoods Tarheel,” including his “rumpled look,” “mountain nature,” and “rural artlessness.” The article made it seem miraculous that, given Griffith’s humble southern upbringing, he was able to act in a fashion suitable for the company of other civilized human beings, let alone become a successful Hollywood actor.19

Magazine articles often referred to Griffith as ‘the real L’il Abner’ and consistently pointed out his lack of sophistication, though he held a degree in music from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and was an adept actor and comic.

Jim Nabors, Griffith’s costar on The Andy Griffith Show and the star of his own CBS sitcom, Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., also allowed his character, Gomer Pyle, to become his public persona—even well after his show went of the air in 1969. By then a millionaire with diverse business interests, the rural Alabama native put forth a great deal of effort to play the part of a humble rube. In a Newsweek article, Nabors and Griffith discussed their shared business manager, but aimed to distract readers from thinking too much about their financial affairs by claiming that they initially did not like him because “his teeth were too close together.” The sound-bite made the men, both university graduates, come of as rustic and uneducated as they employed a backwoods way of judging a man’s character and ability to oversee their financial solvency.

Syndication

It would be easy to dismiss the lines that were blurred between actors and their characters as being troubling for the actors only, but doing so ignores the impact that television has on its audience. Viewers unwittingly draw their perceptions of the world from television, whether the program is educational, or entertaining. In fictitious programs, television becomes more believable and informative when the character or action on the screen coincides with real life. Because the actors from The Andy Griffith Show, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. often adopted aspects of their characters for the benefit of the public, it is not a stretch to say that television viewers may have perceived other parts of the shows as carrying over into real life as well.20

Researchers have demonstrated in numerous studies that people inadvertently gain knowledge from watching television, as it provides images both familiar and unfamiliar. For viewers in rural areas and the South, rural-themed shows illustrated relatively familiar, albeit idealized images of their lives. Southern people routinely displayed kindness, honesty, community spirit, and a willingness to help others. They were also overtly religious. Tennessee Ernie Ford, Andy Griffith, and Glen Campbell were often shown singing Christian hymns on their respective programs. Hal Himmelstein argues in Television Myth and the American Mind that rural programs tended to focus on the “transcendence of material wealth through traditional values.” This stood in stark contrast to portrayals of southerners in the news, which alternately showed them as racist and/or poverty-stricken to the point of depravity. By embracing the harmless, humorous hick, rural comedy privileged, for southern viewers, the more innocuous and charming traits of their region over very real issues of racism and poverty.21

Rural shows and characters were instructive, illustrating a way of life and a group of people that were likely unfamiliar.

But for the millions of rural comedy watchers living outside of the South, these programs told a different, potentially less flattering story. Rural shows and characters were instructive, illustrating a way of life and a group of people that were likely unfamiliar. There were a significant number of southerners living outside of the South in the 1950s and 1960s, but they were often despised and treated poorly in their newly adopted communities. Also, many northern men had spent time in the South for training during World War II, but most of the training locations were in remote areas, where living conditions were at their worst. In addition to the myriad preconceived notions that non-southerners may have held about the South based on both personal experiences and nightly newscasts, rural comedy served as another signifier of southern backwardness. Traits that were seen positively among many southerners carried potentially negative connotations among outsiders. For example, a focus on traditional values made characters look moral, but also quaint and estranged from mainstream culture.22

The fact that many of the recurring characters in rural shows, particularly the humorous ones, were portrayed as dimwitted bumpkins served as potential evidence for the assertion that southerners were backward. On The Andy Griffith Show, moonshine distiller Rafe Hollister, the mountain-dwelling Darling family, Ernest T. Bass, and simpletons Gomer and Goober Pyle all appear in ill-fitting, dirty, and shabby clothing, which suggests a lack of financial resources and hygiene. In addition to these visual cues, their characters also have exaggerated southern accents, and frequently misuse or mispronounce words, suggesting a lack of education and intelligence. The same traits apply to all of the characters on The Beverly Hillbillies, depicting the rural South as a place inhabited by people who do not live by the same intellectual standards as other Americans.23

For Nabors and other stars of rural sitcoms, personas they created and cultivated during the 1950s and ’60s are continually propelled— stuck in syndication.

Television’s effects only escalate when the line between the character and the actor is purposely blurred or removed. Given the consistency between the behavior of the characters and the behavior of the actors in settings outside of their shows, one cannot fault the viewer for thinking that outlandish characters like the Clampetts and Gomer Pyle have a basis in real life. Obviously, that credibility helped some actors on rural shows find new parts, but such roles were often typecast. Out of the four lead actors on The Beverly Hillbillies, only Buddy Ebsen landed consistent work after the show, becoming a cast member on Barnaby Jones. None of the actors from either Petticoat Junction or Green Acres went on to do anything of note, and the same applied to much of the cast of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. George Lindsay, who played Goober Pyle on The Andy Griffith Show and its successor, May-berry RFD, found himself in sporadic movie and television roles that spoofed his earlier character. He later played a similar role on the CBS rural variety show Hee Haw, but afterward, his career options dwindled. Ultimately, he developed a terrible drinking problem, an issue he attributes to his inability to escape the long shadow of Goober Pyle.24

As for Gomer Pyle, Jim Nabors never matched the level of fame he found in rural comedy, going on to host a number of short-lived sketch comedy shows and taking on a few movie and television roles that spoofed his most famous character. More than forty years later, he still can’t escape the work of fiction he left behind. When announcing that Nabors had married his longtime male partner in 2013, the Daily Mail joined media outlets all over the world in proclaiming, “Gomer’s Gay!” For Nabors and other stars of rural sitcoms, personas they created and cultivated during the 1950s and ’60s are continually propelled—stuck in syndication.25

Sara K. Eskridge is a native of Virginia and holds a PhD from Louisiana State University. She currently lives in Richmond, Virginia, where she teaches at John Tyler Community College. She has previously published with the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography.NOTES

- Susan King, “Just Like Gomer, Jim Nabors Remains the Optimist,” Los Angeles Times, June 2, 2000, accessed June 16, 2014, http://articles.latimes.com/2000/jun/02/entertainment/ca-36464.

- Paula Marantz Cohen, Silent Film and the Triumph of the American Myth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 154; Randy Roberts and James S. Olson, John Wayne: American (New York: Free Press, 1995), 211–213.

- Karen Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 83.

- Jack Temple Kirby, Media-Made Dixie: The South in the American Imagination (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986), 230; J. W. Williamson, Hillbillyland: What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 12– 14; Jim Goad, The Redneck Manifesto: How Hillbillies, Hicks, and White Trash Became America’s Scapegoats (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998), 16.

- Sidney Skolsky, undated column, Folder 23 “Tennessee Ernie Ford,” Box 10, Collection 299 “Bob Thomas Papers,” Performing Arts Special Collection, UCLA; Allison Graham, Framing the South: Hollywood, Television, and Race During the Civil Rights Struggle (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 112.

- Pete Martin, “I Call on Tennessee Ernie,” Saturday Evening Post, September 28, 1957, 35; Thomas, undated and unattributed columns; Goad, 89; John Shelton Reed, Southern Folk, Plain and Fancy: Native White Social Types (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988), 43.

- “More Than Meets the Eye,” TV Guide, March 1, 1958, 17– 19; “This Rebel’s From New York,” TV Guide, September 5, 1958, 28– 30; “Nick From Nanticoke,” TV Guide, March 1, 1958, 12–15.

- “The Unreal McCoy,” TV Guide, April 7, 1962, 8– 10; TV Guide, February 15, 1958, 28– 29; Graham, 113; Ibid., 113– 114.

- Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 189; Ibid.; Graham, 113–114.

- “Haute Couture, Hillbilly Style,” TV Guide, March 9, 1963, 6–8; “She’ll Have to Settle for Tempura,” TV Guide, August 24, 1963, 9; “The Rich Rubes,” Newsweek, September 9, 1963, 56.

- Paul Henning, Interview with Bob Claster, Archive of American Television, Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Foundation, September 3, 1997. Accessed June 16, 2014. http://www.emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/paul-henning.

- “The Rich Rubes,” 56; Graham, 114; “A Lot of Hostility,” TV Guide, May 22, 1965, 12–13.

- “November 3, 1968 script,” Box 20, Collection 36, “Smothers Brothers Television Scripts and Production Material,” Performing Arts Special Collection, UCLA.

- Eliot Tiegel, “Campbell Quits as Sideman to be Frontman on Summer TV’er,” Billboard, February 17, 1968, 16; “Living Proof of What a Diet of Hog Jowls Can Do,” TV Guide, June 15, 1968, 16.

- Digby Diehl, “Wooowheee! Ah Been Busier Than a Three-Headed Woodpecker!,” Folder 4 “Glen Campbell,” Box 10, Collection 299, “Bob Thomas Papers,” Performing Arts Special Collection, UCLA; Gloria Paternostio, “Glen Campbell: The Man Behind the Easy Manner,” Family Weekly, June 27, 1971, 14–15.

- TV Guide, August 23, 1957, 26.

- Graham, 101; Lawrence Eliot, “Yokel Boy Makes Good,” Coronet, October 1957, 107; Gilbert Millstein, “Strange Chronicle of Andy Griffith,” New York Times Magazine, June 2, 1957, 17; Graham, 104.

- “The Cornball with the Steel Trap Mind: He’s Every Inch the Hick Until He Settles Down to Business,” TV Guide, January 28, 1961, 17–19.

- Graham, 100–101; Donald Freeman, “I Think I’m Gaining on Myself,” Saturday Evening Post, June 25, 1964, 68–70.

- J. Fred McDonald, One Nation Under Television: The Rise and Decline of Network TV (Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing, 1993), 154; Comstock, 93–95.

- Ibid., 71; Hal Himmelstein, Television Myth and the American Mind (New York: Praeger, 1994), 98; Edward Campbell, The Celluloid South: Hollywood and the Southern Myth (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008), 194; Graham, 5.

- American Research Bureau, US Television Audience, January 1964; Harkins, 176–177; Graham, 97–98.

- Mary Ann Watson, Defining Visions: TV and the American Experience since 1945 (Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers), 1998, 24; Don Rodney Vaughn, “Why the Andy Griffith Show Is Important to Popular Cultural Studies,” Journal of Popular Culture 38, no. 2 (1994), 408.

- “Accepting Goober,” People, November 11, 1996, 86.

- “Gomer’s gay! Jim Nabors, actor best known for playing TV character Gomer Pyle in 1960s marries male partner of 38 years,” Daily Mail, January 30, 2013, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2270681/Gomers-gay-Jim-Nabors-actor-best-known-playing-TV-character-Gomer-Pyle-1960s-marries-male-partner-38-years.html, accessed July 14, 2014.