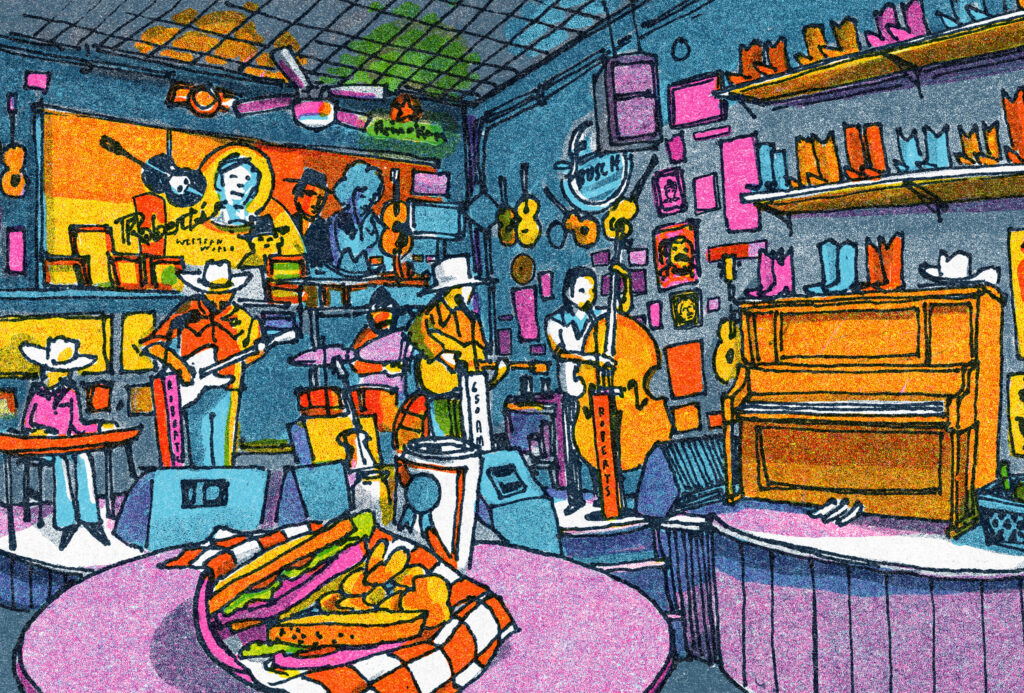

“‘It’s Grand Ole Opry Time—Another big Prince Albert show with Ernest Tubb.’”

Historians rely on documents from the past that have been preserved in archives, museums, libraries, sometimes basements and attics. What gets saved and what gets tossed out is often a matter of luck or circumstance. One of the more interesting cases is the fate of the tobacco industry’s internal documents. Long considered the most secretive of American industries, cigarette manufacturers zealously guarded access to their company files. Cigarette manufacturers would go so far as to ship overseas the results of their own internal research linking cigarettes with disease or transfer material to their legal counsel so that incriminating documents could be shielded from the prying eyes of government investigators and plaintiff’s attorneys by attorney-client privilege. That has all changed. Millions of pages of industry documents are but a few clicks of a computer mouse away. Contained within the 1998 Tobacco Industry Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the major cigarette manufacturers and forty-six states, five territories, and the District of Columbia is a provision requiring each company to maintain an online archive of the documents released during litigation. Available through the web (see here, here, or here) and containing millions of pages, these archives have been a rich source for scholars studying the cigarette industry’s internal research, marketing practices, and massive public relations and lobbying efforts over the years. Public health scholars have made the most use of the industry archives, digging deep into the records to uncover the industry’s scientific research on smoking and health, cigarette design, and extensive youth marketing activities.1

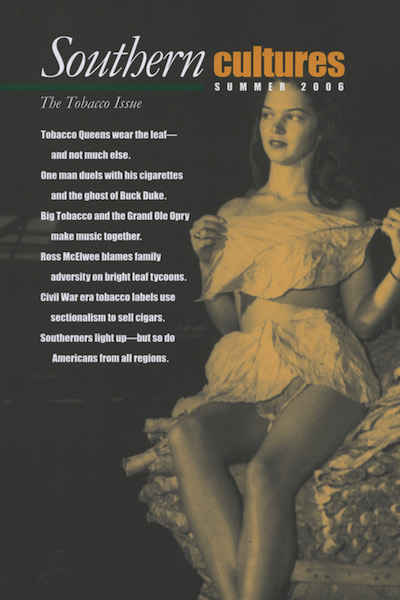

Historians, however, have been slow to take advantage of these records, overlooking this important new source for the study of modern American popular culture and business history. Big tobacco embraced advertising like no other industry in American life, incorporating every new innovation in marketing, advertising, and hucksterism to persuade the nation that smoking was fun, relaxing, pleasurable, and, of course, harmless. While we tend to associate the American public’s initial infatuation with the cigarette with Buck Duke and the development of the Bonsack cigarette rolling machine in the 1880s and 1890s, cigarettes actually occupied a distinctly minor and disreputable segment of the tobacco market until World War I. It wasn’t until the 1920s that cigarettes emerged as the predominant form of tobacco use, surpassing chewing tobacco, pipes, and cigars. The jazz decade, with its patina of prosperity, saw Americans take to the cigarette in ever increasing numbers as tobacco manufacturers blanketed the nation with slogans such as “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” and “Old Gold, Not a cough in a carload.” Emily Post told women that to be up-to-date they had to have cigarettes handy in the home: “There is not a modern New York hostess, scarcely even an old-fashioned one, who does not have cigarettes passed after dinner,” she explained to her readers, even as she appeared in advertisements for Old Gold cigarettes. Cigarette sales rose astronomically, pausing only briefly in the early years of the Depression. By the mid-1950s, 57 percent of men and 28 percent of women over the age of fifteen smoked regularly. Per capita consumption that year stood at 3,293 cigarettes for every man and woman over the age of fifteen.2

Moving all those cigarettes out of the factory and into the lips of the American public took a sustained and heroic advertising effort. No marketing innovation was too novel for the industry. The American Tobacco Company pioneered the practice of skywriting, emblazoning “Lucky Strike” in the heavens above New York, Atlanta, and other major American cities. The tobacco companies were pioneers in radio sponsorships, including “Your Lucky Strike Hit Parade,” “Kay Kysers Kollege of Musical Knowledge,” and the “Grand Ole Opry,” and in television sponsorships. Philip Morris advertised cigarettes on “I Love Lucy,” and Winston sponsored both the “Flintstones” and “The Beverly Hillbillies.” Cigarette manufacturers avidly sought to reach the audiences for sports events through Winston Cup NASCAR racing, Marlboro formula one racing, and Virginia Slims women’s tennis. Philip Morris innovated in the use of massproduced, preprinted billboards to blanket cheaply the nation’s highways with the image of the Marlboro cowboy after the industry withdrew from television advertising in 1971. It is no exaggeration to say that America’s contemporary consumer culture, with its emphasis on pleasure and delight, rode into town on the back of a carton of cigarettes and was carried into the home on the back page of Life Magazine, invariably a full-color cigarette advertisement. The radio and, later, television inundated American consumers with cigarette promotions. If it involved modern advertising media, the cigarette was there. Indeed, it was everywhere.3

Smokin’ on Stage

The Grand Ole Opry is just such a case. Using country music to sell something wasn’t new; it reached back to the use of string bands in nineteenth-century patent medicine shows and continued with the advent of radio. The Opry itself came into being to promote Nashville’s National Accident and Life Insurance Company. In 1938 R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. (RJR) began sponsoring a thirty-minute national broadcast of the Grand Ole Opry, using the program as a vehicle to promote Prince Albert Smoking Tobacco and the Cavalier and Camel cigarette brands. W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, general manager of the Burrus Mills and Elevator Co., employed Bob Wills to promote his firm’s Light Crust Flour, launching the musical careers of both Wills and O’Daniel, who sang himself into terms in the Texas governor’s mansion and the U.S. Senate. RJR wasn’t even the first tobacco company to use a radio music-and-variety program to advertise its product; that distinction belongs to the Winston-Salem firm’s New York-based archrival, American Tobacco, whose sponsorship of the “Lucky Strike Hit Parade” began in 1928.4

Preserved in the RJR files are some 241 original broadcast transcripts and fragments of performances, covering the years 1948 to 1959. (I’ve not been able to locate scripts for 1951 and 1955.) To many, these are the golden years of country music: the years of Minnie Pearl, who appears in at least 181 of the extant scripts; Hank Williams Sr., who appears in 10; Roy Acuff (15 scripts), Ernest Tubb (36), Rod Brasfield (164), Faron Young (26), and many others. These scripts are not archived in university or music libraries, however; instead, they have sat safely tucked away in the files of RJR, only pried loose in the last decade by the litigation discovery process and now available to us on the internet.

In an earlier day, temperance advocates had denounced cigarettes as a pestilential evil on par with demon rum. Henry Ford dubbed the cigarette a “little white slaver.” Between 1893 and 1921, fifteen states, largely in the South and West, passed some form of prohibition against the sale, manufacture, or distribution of cigarettes. Even in the Opry’s home state of Tennessee, cigarette sales had been banned from 1897 to 1919. The animus against cigarettes faded after World War I. U.S. troops stationed in France had smoked cigarettes at the encouragement of the military. The Salvation Army and YMCA had distributed cigarettes to the troops in France, even as they worked to limit alcohol. After the war, temperance advocates, satisfied that the evil of drink had been vanquished by national prohibition, dropped their objection to the cigarette. In the 1910s, tobacco manufacturers introduced milder cigarette blends, with a lighter, easier-to-inhale smoke that facilitated the absorption of high levels of addictive nicotine. Pioneered by RJR’s Camel and American Tobacco’s Lucky Strike brands, the nation was flooded with a more palatable form of nicotine addiction and blanketed by an avalanche of cigarette advertising. By the 1920s, walking a mile for a Camel or reaching for a Lucky “instead of a sweet” had become part of the nation’s culture.5

Typically, each half-hour national broadcast of the Opry opened with a prerecorded advertisement for Cavalier cigarettes. “Have a Cavalier,” exhorted the radio on August 20, 1949, as Opry announcer Grant Turner declared, “Its Grand Ole Opry Time—Another big Prince Albert show starring Ernest Tubb.” Tubb offered “a great big howdy to all our good friends and neighbors of Prince Albert Smokin’ Tobacco’s Grand Ole Opry!” Turner replied that “whether you roll your own or smoke a pipe, you get more real smoking enjoyment from Prince Albert Smoking Tobacco!” The following week, Hank Williams made an appearance, performing “Lovesick Blues.” Before introducing him, Ray Foley pitched Prince Albert by telling the audience that the tobacco was “kind to your tongue” because it was “specially treated to insure against tongue bite . . . and smoke cool.” Foley, Turner, and the other performers mentioned the sponsor’s products about every three minutes on that particular broadcast.6

Sponsoring the Opry allowed RJR to connect their products with the family and the home and consequently to project a wholesome, domestic image for their products, as this exchange between Grant Turner and Ray Price reveals,

Grant: Ever notice that when parents get together, you can expect them to take out pictures of the youngsters?

Price: Yep, just like when pipe smokers get together, you see them take out those tins of Prince Albert!

Or this exchange connecting smoking and marriage:

Grant: Ray, can you think of things that go together like love and marriage?

Price: Well, there’s horse and carriage. And then, there’s Prince Albert Smoking Tobacco and O.C.B. papers! THAT combination adds up to perfect makin’s cigarettes.7

Sponsoring the Opry broadcasts allowed RJR to identify its smoking tobacco and cigarettes with the authenticity of country music. Johnny Cash, appearing in August 1957, performed “Next in Line” before telling the audience: “The OPRY attracts folks about the same way Prince Albert smoking tobacco attracts pipe smokers.” Rolling your own cigarettes with Prince Albert was easy, Marty Robbins announced right after performing “Who at my door is Standing?”: “ANYBODY can roll up a makin’s smoke expertly with Prince Albert Smoking Tobacco and O.C.B. papers—there’s no trick to it!” Ray Foley followed Hank Williams’s performance of “I Just Don’t Like this Kind of Living” by announcing, “That’s one of my favorite songs—one I like ‘most as much as I like to smoke Prince Albert!”8

RJR was quick to let the public know that smoking felt good; that the smoke was mild; that it would not irritate your tongue, your mouth, and by extension, any other part of the respiratory anatomy: “The smoke FEELS as good as IT TASTES!” It’s a “smooth smoke.” Prince Albert is “so easy on the tongue!” said Grant Turner. Ray Foley added, “That’s not the half of it, Grant! Prince Albert’s choice tobacco is specially treated to insure against tongue bite . . . and smoke cool.” That broadcast ended with the announcer making the pitch for the healthful mildness of Camels: “No other cigarette gives you the same smoking comfort you get out of Camels.”9

Packed with stories and jokes, the half-hour scripts recall the importance of humor to the Opry’s appeal. Rod Brasfield told of his Uncle Cype watching a tug of war at a picnic: “Well sire, Uncle Cype stood there watching them . . . and says, ‘Rodney, wouldn’t it be a whole heap simpler if them fellers just got a knife and cut that rope?’” Minnie Pearl commented on an overweight friend trying on a bathing suit: “Uncle Nabob says he couldn’t figger if June was in the bathin suit tryin’ to get out or outside trying to get in!” Tex Williams bantered, “I was told that if I wanted to find the prettiest, most wonderful gal in Tennessee, to look up Minnie Pearl.” After Minnie swooned from the compliment, Tex chimed in: “Now tell me. Where’ll I find ’er??” The talk quickly returned to the subject that was paying the bills, as Tex continued, “Why Minnie’s as easy on the ears as Prince Albert Smokin’ tobacco is easy on the tongue.”10

In a way, the Grand Ole Opry’s relationship to R. J. Reynolds is much like the South’s relationship to the rich, wonderful culture of tobacco farming, which enabled the small farmer to stay on the land and earn a living. The rituals of raising a crop whose preparation, cultivation, and curing is so time consuming and labor intensive that it takes thirteen months from seed to market is woven into the folk culture of the region. We forget that sharecropping and grinding poverty also came with that cultivation. The culture of cigarettes likewise has an ugly side. We’ve forgotten how pervasive smoking once was as a social ritual. The cigarette was there, the tobacco companies told us, to offer us sheer pleasure, relaxation, and reassurance when we needed it. It seemed that everyone smoked. What could be the problem? Indeed. Today, lung cancer deaths alone currently run about 124,000 per year; add all the other tobacco-related causes of premature death—other cancers and cardiovascular and respiratory ailments—and the figure rises to just over 438,000 annual deaths. Cigarette-related disease has taken many country performers. Rabon Delmore, Eddie Rabbit, Merle Travis, and Tex Williams all died of lung cancer; Ernest Tubb and Johnny Paycheck were stricken with emphysema. The Opry evoked the authenticity, simplicity, and community of an earlier musical culture. In marketing a similar world of delight, well-being, and community built around the rituals of smoking, Big Tobacco obscured the cigarette’s deadly consequences.11

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Louis Kyriakoudes is director of the Albert Gore Research Center and specializes in the social and economic history of the 19th and 20th century United States in global context. His research has explored the economic, demographic, and cultural history of American South and the history of the global cigarette industry. He serves on the editorial board for Southern Cultures.

Header image: Opry Performers, including Eddy Arnold, Pee Wee King, Harry Stone, and Minnie Pearl, appear alongside sponsor Camel and the brand’s Camel Caravan. Shot at the Parthenon in Nashville, TN. Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry Archives.

NOTES

- Stanton A. Glantz, et al., The Cigarette Papers (University of California Press, 1996), 241–47; Carrick Mollenkamp, Adam Levy, Joseph Menn, and Jeffrey Rothfeder, The People vs. Big Tobacco: How the States Took on the Cigarette Giants (Bloomberg Press, 1998) provides an interesting journalistic account of the tobacco litigation of the 1990s. Thomas R. Frieden and Drew E. Blakeman, “The Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths That Undermine Tobacco Control,” American Journal of Public Health 95 (Summer 2005): 1500–1505 offers a succinct summary of current tobacco-control research. Florida, Minnesota, Mississippi, and Texas had already reached settlements with the tobacco industry and, thus, were not party to the Master Settlement Agreement.

- Emily Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home (Funk & Wagnalls, 1922), 169; “Blindfolded . . . in scientific test of leading cigarettes, Mrs. Emily Post selects Old Gold,” New York Times, 30 April 1928, 6; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Research Data & Reports: Smoking Prevalence Among Adults, http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/research_data/adults_prev/prevali.htm; accessed 16 January 2006; U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service, Annual Report on Tobacco Statistics, 1956, Statistical Bulletin No. 200 (Government Printing Office, March 1957), 50.

- “Sky Writing, 1922–23,” American Tobacco Company, Bates No. 945194722/4869, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vae80a00, accessed 16 January 2006; William Esty Company, “Television Copy” [Broadcast Transcripts], August–December 1963, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No.: 500412526-500412605, http://tobaccodocuments.org/rjr/500412526-2605.html, accessed 16 January 2006; James J. Morgan, Trial Testimony in Minnesota v. Philip Morris, Inc., 22 April 1998, 13454–56, http://tobaccodocuments.org/datta/MORGANJ042298.html, accessed 25 January 2006.

- Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (University of Chicago Press, 1997), 121–22; American Tobacco Company, “Sold American!”—The First Fifty Years (The American Tobacco Co., 1954), 84. While American Tobacco maintained an extensive manufacturing operation in Durham, North Carolina, its headquarters were lodged at 111 Fifth Ave. in Manhattan.

- Cassandra Tate, Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of the “Little White Slaver” (Oxford University Press, 1999), 159–60; Nannie M. Tilley, The R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 203; Jack E. Henningfield et al., “Reducing Tobacco Addiction through Tobacco Product Regulation,” Tobacco Control 13 (June 2004): 132–35.

- “WSM’s Grand Ole Opry Prince Albert Show,” 20 August 1949, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514566056/6071, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aou03d00, accessed 25 January 2006; “WSM’S Grand Ole Opry Prince Albert Show,” 27 August 1949, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514566072/6083, accessed 25 January 2006. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bou03d00, accessed 25 January 2006.

- “Prince Albert Show,” 28 April 1956, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514621962/1969, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wgr03d00, accessed 25 January 2006.

- “Prince Albert Grand Ole Opry,” 3 August 1957, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514622535/2542, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kjr03d00, accessed 25 January 2006; “Prince Albert Show,” 19 May 1945, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514621987/1994, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zgr03d00, accessed 25 January 2006; “WSM’S Grand Ole Opry Prince Albert Show,” 18 February 1950, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514566441/6450, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bpu03d00, accessed 25 January 2006.

- “Prince Albert Show,” 28 April 1956; “W.S.M.’S Grand Ole Opry Prince Albert Show,”. 29 October 1949, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514566222/6238, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/oou03d00, accessed 25 January 2006; “Prince Albert Grand Ole Opry,” 3 August 1957.

- “Et: Open With Cavalier Spot Recording 563 – #2 [Grand Ole Opry Script],” 2 September 1950, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514566754/6767, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dqu03d00, accessed 25 January 2006; “It’s Grand Ole Opry Time! Another Big Prince Albert Show! Starring—Tex Williams!” 20 June 1953, R. J. Reynolds, Bates No. 514620293/0305, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gnr03d00, accessed 25 January 2006.

- Pete Daniel, Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures since 1880 (University of Illinois Press, 1985), 206; “Annual Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Productivity Losses—United States, 1997–2001,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 54:25 (1 July 2005): 625–28.