A dark spirit lives on your porch,” the medium told me. Excuse me? Prickles of dread and fear blossomed in my chest. What the hell am I supposed to do about that? I was only beginning my journey in ancestor veneration—working through my fears of the dead in general and dark spirits in particular with the help of a powerful medium whom I trust implicitly. I am the world’s scariest horror scholar—I watch scary movies with my fingers in my ears, for gosh sakes! And now something fearsome was just outside my front door.

“Oh, don’t worry,” the medium laughed. “Every time it tries to come in, your grandmother comes out the hallway and stares it down, daring it to come into my grandmother’s baby’s domain.”

I smiled, fear and dread now replaced with pride and confidence in her protection of my home. Sixteen years after her death, my grandmother was still my defender.

The South is haunted. I often refer to my hometown of New Orleans as the “Land of the Dead,” for so much blood has been spilled in and over my city that death seems to permeate the air. It can be both suffocating and invigorating. Mistakenly thought of as a place time forgot, New Orleans is a town that accepts the presence of the dead and their influence on quotidian life. Echoing this feeling, author Phyllis Alesia Perry speaks of her love for “a certain place in Alabama . . . where stories seem to bubble up from the ground.”1

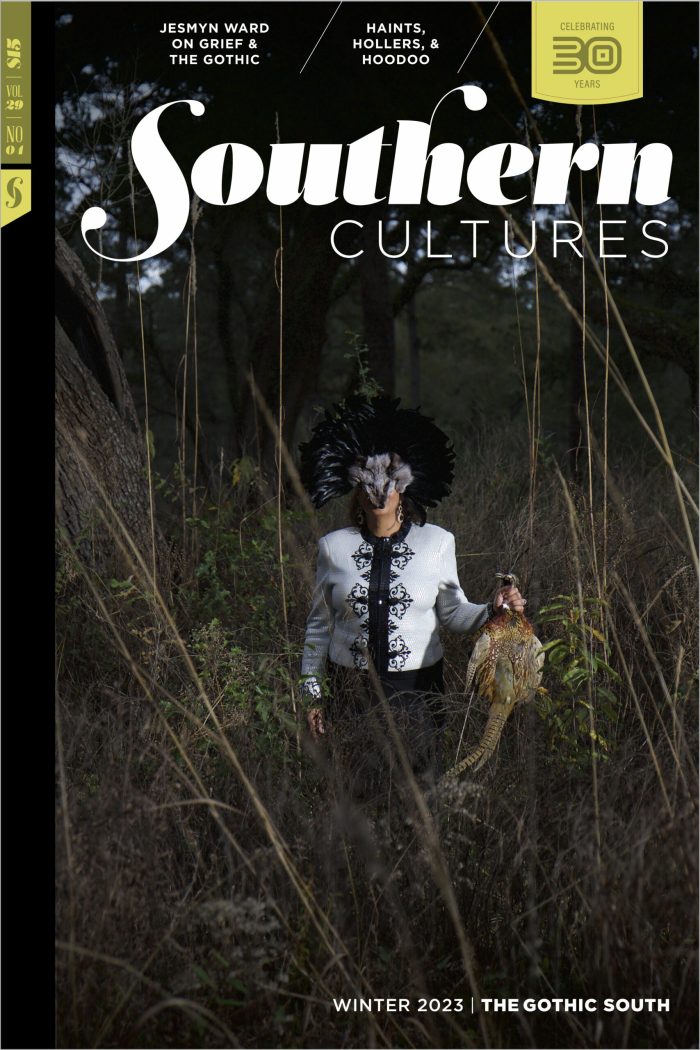

This issue is dedicated to unpacking the storied Gothic South. Its key concepts center haunting: the presence of ghosts that bring discomfort to the living; the waves of terror and trauma manifesting as deep melancholia, seen, for example, in the classic works of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor; the emphasis on the old, the decrepit, and the remnants of a past that often never was—such as the still-living lie that enslavers and the enslaved lived in harmony. This melancholia emerged after a devastating loss in a war against fellow Americans that left both the land and the (white) southern sense of self in ruins.

The subject of southern ghosts offers many more ways to consider the haunted nature of the South, however. Two of the most prominent approaches within this issue deal with haunting and the overlapping sense of time. We see explicit haunting in K. Ibura’s “A Girl, a Man, a Storm, a City,” as we revel with ghosts in the aftermath of Katrina. We also encounter implicit haunting in the photography of Jared Ragland (introduced by Catherine Wilkins) and Kristine Potter (alongside a story by Rebecca Bengal), and in the poem by Golden. As Jesmyn Ward observes in her interview with Regina N. Bradley, “there is more to the world than what we see on the surface.” The authors and artists featured in this issue wrestle with how we live with our ghosts, be they directly in front of us or a steady, pulsing presence in the background.

A guiding question seems to be “How do you stop a haint?” My response is, are you sure you want to? Two perspectives must be examined. First, we cannot and should not exorcise all of our ghosts. I benefit, for example, from the influence of my grandmother’s ancestral protection as I move through my life. She guards against entities of which I am barely aware. The horror genre has long grappled with the violence of Catholic exorcism, including its catalog of demons, tools of assessment, and criteria for banishment. Meanwhile, Protestantism somehow ignores the presence of ghosts—of course, the Holy Spirit doesn’t count, nor does Jesus, a big exception—while simultaneously advocating for the wholehearted expulsion of every supernatural entity outside of the Holy Trinity. In “The Appalachian Murder Ballad,” Julyan Davis speaks of “nescient fatalism” expressed as a “stoic acceptance existing without specific foreknowledge.” This melancholic fatalism manifests when someone encounters a ghost they do not want to exorcize, yet they remain ignorant of how to live with the spirit and even anticipate and embrace its presence in their life.

Second, living with spirits is often unsettling. Too many times this lack of peace is understood as animosity from the spirits—a misreading that brings discomfort. Hoodoo and holler magic teach us that “not all haints mean for evil,” although spirits often reveal things we do not want to see or are not ready to know. Stephen Simmons’s essay, “Mystery of the Talking Skull,” speaks to how specters, especially those born of ambiguous circumstances, power folk beliefs and strain family understandings. Hoodoo and holler magic are, like many poor Black and white folks of the South, distant relations of each other. Hoodoo, often joined with conjure, is a set of religious beliefs and practices that center on ancestor veneration, justice, and a botanical practice of healing and harm known as rootwork. It is heavily rooted in religions of the African diaspora, with both Indigenous and European influences. Holler magic, often coupled with mountain magic, is a set of religious practices and beliefs grounded in European folk magic, with botanical traditions of healing and harm containing both Indigenous and, to a lesser extent, African influences. Holler magic is regionally attached to the peoples of Appalachia, while Hoodoo is specifically attached to the Black South. Both are often supplemental practices for folks excluded from the austere religions of middle- and upper-class white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Holler and Hoodoo are practices that require blood, sweat, and a lot of dirt, from goofer dust (graveyard dirt) to mountain soil. These faiths are embodied because they require hard work.2

Spirits tell their stories and reveal their truths to us without regard for how we feel about them—and that is where so much fear originates, with the harsh realization that we lack full control over them. The true solution to living with haints is to work with them toward a mutual respect, as we see in Kimberly Anderson’s “Night Walker,” where the main character, Tea, encounters a mysterious church service and must later determine if a fellow walker is friend or foe. Our mothers, grandmothers, and aunts teach us the rules to living productively with the dead. The dead want, nay, deserve their due—be it a share of food, an offering (as seen in Kameelah Martin’s analysis of Kara Walker’s piece, “Night Conjure”), or a terrible sacrifice (as in John Jennings’s “Mama Possum”).

This issue also tackles the malleable nature of time. Here, it is necessary to shift our concept of time from Western linearity to the concept of Sankofa, in which the past, present, and future exist within the same space. Critic Bonnie Barthold terms this “Black Time,” in which “[metaphysically] being was equivalent to duration: each moment embodied a recurrence of a past moment, and implied was a potential future recurrence.” I have written before about how “the act of haunting conflates and confuses linear time, disrupting and opening a space for concurrent time existence with the ghosts acting as ‘agents of cultural memory and cultural renewal.’” Haunting collapses time and position, allowing southerners to be both the ghost and the haunted, existing in a unique space of simultaneity in which our ancestors haunt those of us who are alive.3

The overwhelming dread of the past—the twin southern legacies of the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of Africans—creates a fearful alienation. This disquiet is meaningfully raced in Black and white, and the creation of a false binary—as Alena Pirok describes the sharing of ghost stories as mythical proof of friendship between elite white southerners and their Black neighbors in “Specters of the Mythic South”—does not diminish its significance. There remains a difference between being trapped in the past and existing healthily with its weight and significance. Black southerners who acknowledge the trauma of the past while living with and learning from the ancestors in the present can build upon their legacies for the benefit of their descendants.

The reality of the South is that our haunting is continuous, sustained—it has never broken and, in this understanding, will never break. This is a statement of opportunity rather than doom: understanding your present as coexistent with an active past acknowledges and sanctions the good haints that we need to remain around us and influence not just the present but the future. In the traditions of Sankofa, we must weave together and recognize the interrelated nature of the past, present, and future, for none exists alone. The goal of this special issue is to acknowledge, listen to, and honor past traumas while holding space for the ancestors to both heal and bring justice in all the unique ways that each contributor has dared to document.

This essay introduces the Gothic South issue, guest edited by the author.

KINITRA D. BROOKS is the Audrey and John Leslie Endowed Chair in Literary Studies in the Department of English at Michigan State University. Dr. Brooks specializes in the study of Black women, genre fiction, and popular culture. She has coedited The Lemonade Reader, and her two other books are Searching for Sycorax: Black Women’s Hauntings of Contemporary Horror and Sycorax’s Daughters.