What is the future of textiles? Read news headlines, from business to environment to fashion, and you would be justified in pointing to the movement of nearly all textile production overseas, where supply chains are opaque and workers are often exploited; the prevalence of synthetic and toxic materials; and the massive and devastating volume of waste produced by the fashion industry. You might note the triumph of artificial intelligence over individual creativity, or 3D printing over skilled craftsmanship. Where quilts were once treasured and passed down, and jackets were mended or repurposed, today’s consumers purchase and discard fiber goods impulsively. Simultaneously, many of the pieces we acquire are completely alien to us; we know nothing of their provenance, the processes by which they were created, or the people who oversaw their construction. Waste, labor abuse, environmental destruction, knowledge loss—these are all realities facing the present-day textile industry, but they are not the only stories.

We have long believed that a different way forward is possible—one that mends the ruptures between seed and shelf, maker and wearer. This issue aims to highlight some of the scholars, artisans, entrepreneurs, and creatives who dare to imagine and reimagine it.

The question of textile futures has circulated in our minds over the past year, as we have considered the future not only of our organization, Project Threadways, but of the industry, artisan craft, supply chains, and local manufacturing. Project Threadways is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that records, studies, and interprets history, community, and power through the lens of fashion and textiles. From raw materials to finished goods, we seek to understand the impact of textiles on our community, nation, and world. After all, every textile story is necessarily a global one. As historian Sven Beckert writes, “The empire of cotton, and with it the modern world, is only understood by connecting, rather than separating, the many places and people who shaped and were in turn shaped by that empire.”1

The history of textiles is nearly as long and complicated as that of human civilization. Project Threadways operates out of The Shoals, our community in northwest Alabama that includes the small cities of Florence, Muscle Shoals, Tuscumbia, and Sheffield. As in many communities around our nation and globe, people have been growing cotton and making textiles here for centuries, starting in the eighteenth century with the Chickasaw and Cherokee nations, until the federal government forcibly removed them from their land between 1837 and 1838. Native lands were then sold and cultivated by white settlers, who put more land into cotton production, growing mass enslavement. Even before the Civil War, three textile factories operated in Lauderdale County, where our headquarters sits and where Natalie was born, processing cotton grown by enslaved peoples. British industrialists bought cotton from the American South and shipped it to their new factories to spin, weave, and sell to markets around the world, triggering a cotton boom. In 1860, the Globe Factory on Cypress Creek, just outside of Florence, employed more than three hundred people, including women and children; the mills were burned by the Union Army in May of 1863.2

The Civil War devastated the local land and economy, but the latter slowly recovered, with textiles remaining central. In 1950, about fifty-four thousand employees worked in seventy-two mills in Florence. East Florence mills fostered a thriving industrial community; Natalie’s great-grandmother, grandmother, aunt, and their friends all worked and lived in the mill village after moving from the rural county to “town.” Around the same time, the underwear and T-shirts being produced by these mills became outerwear. In the 1970s, Lexington Fabrics and Tee Jays Manufacturing opened in Florence, and the city became known as the “T-shirt capital of the world.” Following the signing of NAFTA in 1994, factories that had once employed thousands shuttered as manufacturing was outsourced overseas. Since then, the United States has lost more than five million manufacturing jobs, and over seventy thousand factories have closed due to the growing trade deficit in manufactured goods with China, Japan, Mexico, and other countries.3

It was a curious time to begin making clothing locally and by hand, given rampant offshoring, but an auspicious one.

In 2000—just six short years after NAFTA was adopted—Natalie returned to her home in The Shoals to conduct oral history interviews for a documentary film, Stitch, and to create a collection of two hundred unique T-shirts, handcrafted and embroidered by local quilters and artisans. It was a curious time to begin making clothing locally and by hand, given rampant offshoring, but an auspicious one. The work, originally called simply “Alabama,” is today the foundation for three connected branches of our organization: Alabama Chanin, a brand that designs and produces textiles and fashion through commitments to sustainability, organic and domestic supply chains, and local manufacturing; The School of Making, which offers workshops and educational experiences; and Project Threadways, the scholarly and interpretive humanities arm. Even from its earliest days, this work incorporated a clear social and ecological mission into its business model. Local history and heritage is never too distant; today, the organization operates out of a factory previously owned and operated by Tee Jays. For years, the production team has purchased organic cotton from Texas and spun it into fabric at mills in North Carolina. The organization created local jobs, paying artisans upwards of $20 an hour for work that might pay a sewist 20 cents overseas. Artisans and educators highlighted and taught techniques such as appliqué and embroidery, which were historically passed down over generations of families but have been abandoned over time. They conducted research, pieced together supply chains, and dreamed of a cleaner, safer, more equitable industry.

That future has not arrived, and today, the mission transcends business. In 2023, Natalie decided to bring Alabama Chanin, The School of Making, and Project Threadways together as a single 501(c)(3) not-for-profit to ensure a future for this work. While quietly sourcing domestically, creating local jobs, paying fair wages, and celebrating craft may have sufficed twenty years ago, today’s broken industry requires a more radical approach. It requires teaching craft skills to broad audiences so that they do not disappear from our global lexicon. It requires preserving the cultural heritage of an industry that shaped the place where we live, and so many other places around the world. It requires examining and atoning for the ways that peoples and the land have historically been exploited. It requires the urgent shift from a global fast-fashion industry to mission-driven businesses, collectives, and nonprofits like ours that seek to create a new path forward. It requires a new model. At stake are the past, present, and future of how we make—and the consequences for people and planet.

As part of this transition to a not-for-profit, Project Threadways held a constituent study, interviewing staff members, collaborators, and our larger community about what they want to see from this work going forward. They expressed a desire to preserve the stories of people who have shaped the textile industry and, in response, Project Threadways is expanding our oral history collection through a collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Study participants want to engage a broader audience with this work, so we are beginning to offer scholarship opportunities for workshops and taking educational programming on the road. They want more involvement in the local community; we are raising funds to renovate a historic building in downtown Florence that will serve as a maker lab and interpretive third place. The future that we want to live in is attentive to history, culture, place, creativity, and humanity.

We are not alone—far from it. The past year of transitioning the organization has led us into the paths of brilliant scholars, activists, artists, and thinkers who envision and demand a different way of making and consuming. They include Rebecca Burgess, who founded the nonprofit organization Fibershed to develop and nurture regional fiber systems. And Dr. Diana Baird N’Diaye, an artist, scholar, and curator whose work considers the relationships between making, identity, and social justice. And Lidewij Edelkoort and Philip Fimmano of the World Hope Forum, whose critiques of the fashion industry and insistence on people over profits offer a platform for nuanced dialogues. And the scholars and editors at the Center for the Study of the American South, who acknowledge not only the impact of textiles in the story of our region but also the urgency of this conversation. By making space for research and perspectives that connect craft and community, heritage and healing—that look backward to chart a more sustainable and equitable path forward—that path comes into clearer view.

In these pages, you will find stories that thread together the past, present, and future of textile production, asking questions about where we go from here. Historian Elijah Gaddis takes us to the Loray, in Gastonia, North Carolina, which was once one of the largest textile mills in the country and has since converted into trendy loft apartments. He considers how contemporary adaptive-reuse projects negotiate economic and narrative uses, selling industrial character without accounting for the people and events that once animated the building. Joseph “Chip” Hughes recollects his time fighting for workplace reform with a group of labor, civil rights, and public health activists, whose campaigns have had a lasting impact on social advocacy and worker justice. With documentary photographer Rinne Allen, writer Maurice Bailey and geographer Nik Heynen detail their project to reintroduce indigo, a heritage crop, to Sapelo Island to generate economic development and provide a new future for Gullah Geechee descendants. Folklorist Emily Hilliard interviews weavers at Berea College about the history and evolution of the Student Craft Weaving Department, where new initiatives include gender-neutral baby blankets and a natural dye garden. Ecologist and researcher Makalé Cullen explores the marine present and future of cellulose fibers as the textiles of fast fashion, connecting the South’s offshored manufacturing with waste around the world, from Gulf Coast to Gold Coast. Conceptual artist Libby O’Bryan writes of Sew Co., the working sewing factory she founded with the mission to preserve sewing skills using a new model for worker agency. She describes the project as an experiment in cultural ideals, values, and worth, opening an exchange about labor, craft, and consumption. Fashion designer Marwan Pleasant tells of making beautiful, intricately beaded suits as part of the Black masking Indian tradition in New Orleans, and the role of craft in honoring and evolving culture. Along the way, you will meet Fibershed affiliate organizations in the South who support and champion local farming, spinning, dyeing, weaving, and making, all to design a better fiber economy.

Textile metaphors remain ubiquitous in our vernacular, despite our dislocation from our own fibers’ origins and processes.

Appropriately and deliberately, subjects range widely, though we are interested in the places in which they intersect: labor, community, identity, and power. Each author is mindful of context. They position their art and research within a network of producers, makers, and consumers—global and local. Meanwhile, they interrogate the relationship of their own work to past and future, examining what it might reveal about each.

Textile metaphors remain ubiquitous in our vernacular, despite our dislocation from our own fibers’ origins and processes. We “hang on by a thread” and speak of “moral fiber” and “social fabric.” Staunch beliefs are “dyed in the wool.” The prevalence of these metaphors testifies to the ways in which, as Beckert writes, textiles shaped our world by ushering in an era of uncontrolled capitalism. Consider, however, as the journalist Virginia Postrel has, that we use aphorisms such as “on tenterhooks” or “frazzled,” unconscious of their relationship to textiles. “We speak of life spans and spinoffs and never wonder why drawing out fibers and twirling them into thread looms so large in our language,” she writes. “Surrounded by textiles, we’re largely oblivious to their existence and to the knowledge and efforts embodied in every scrap of fabric.”4

The essays in this issue suggest that the tears between textile histories and futures may be mended. When the people who make textiles, and the act of making itself, become visible, it is impossible to separate the material from the human. It is our deepest hope that, through these stories, we may inspire and facilitate conversation with makers, thinkers, and consumers who will shape a new future.

Natalie Chanin is a designer, artist, writer, and founder of Alabama Chanin, Project Threadways, and The School of Making. She has a Bauhaus-inspired degree in environmental design with an emphasis in industrial and craft-based textiles from North Carolina State University. In 2000, she left a career in Europe and New York City to return to her hometown in The Shoals community of northwest Alabama, to begin the work of sustainable design, craft preservation, organic supply chains, local manufacturing, and the social equity work which culminates in the three organizations today.

Olivia Ware Terenzio is a writer, editor, and arts and culture administrator who works in the American South. She is the associate director of programs and scholarship for Project Threadways, a nonprofit that records, studies, and interprets history, community, and power through the lens of fashion and textiles, and the editorial and marketing manager at the Southern Foodways Alliance, which explores the diverse food cultures of the changing region.

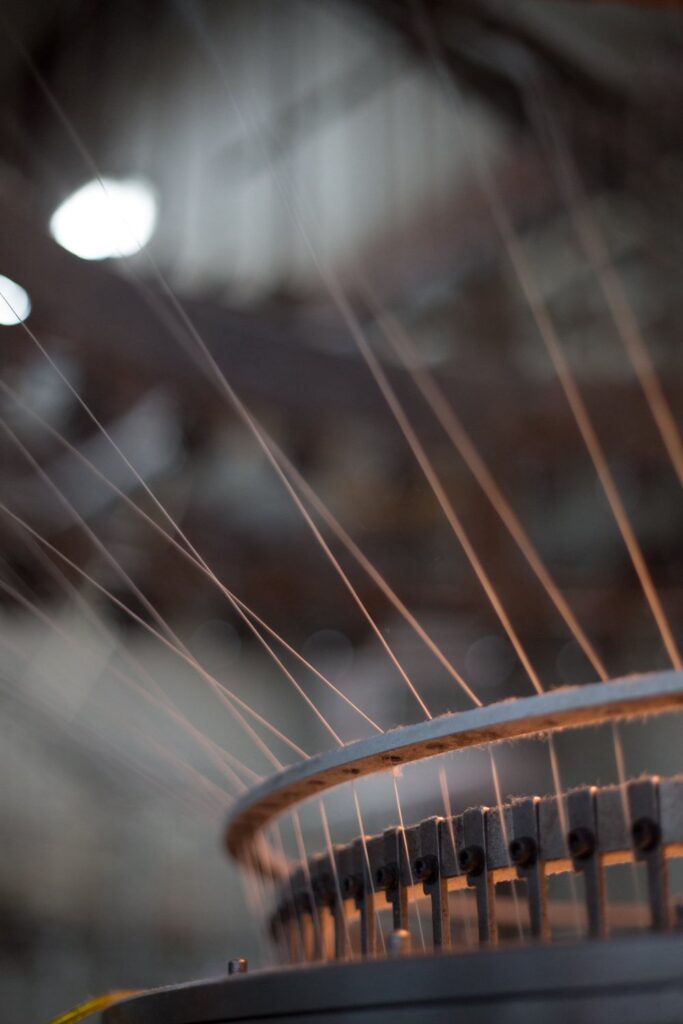

Header image: Bale of organic Alabama cotton awaits spinning, Hill Spinning Mill, Thomasville, North Carolina, 2013. Photo by Rinne Allen.

NOTES

- Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (Vintage Books, 2015), xix.

- “Ante-Bellum Cotton Mills 1840,” The Historical Marker Database, September 2, 2010, updated August 28, 2020, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=83938.

- Carrie Barske Crawford, “Textiles Vital in MSNHA History,” Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area website, May 25, 2020, https://msnha.una.edu/textiles-vital-in-msnha-history/; Robert E. Scott, Valerie Wilson, Jori Kandra, and Daniel Perez, “Botched Policy Responses to Globalization Have Decimated Manufacturing Employment with Often Overlooked Costs for Black, Brown, and Other Workers of Color,” Economic Policy Institute website, January 31, 2022, https://www.epi.org/publication/botched-policy-responses-to-globalization/.

- Virginia Postrel, The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World (Basic Books, 2020), 3.