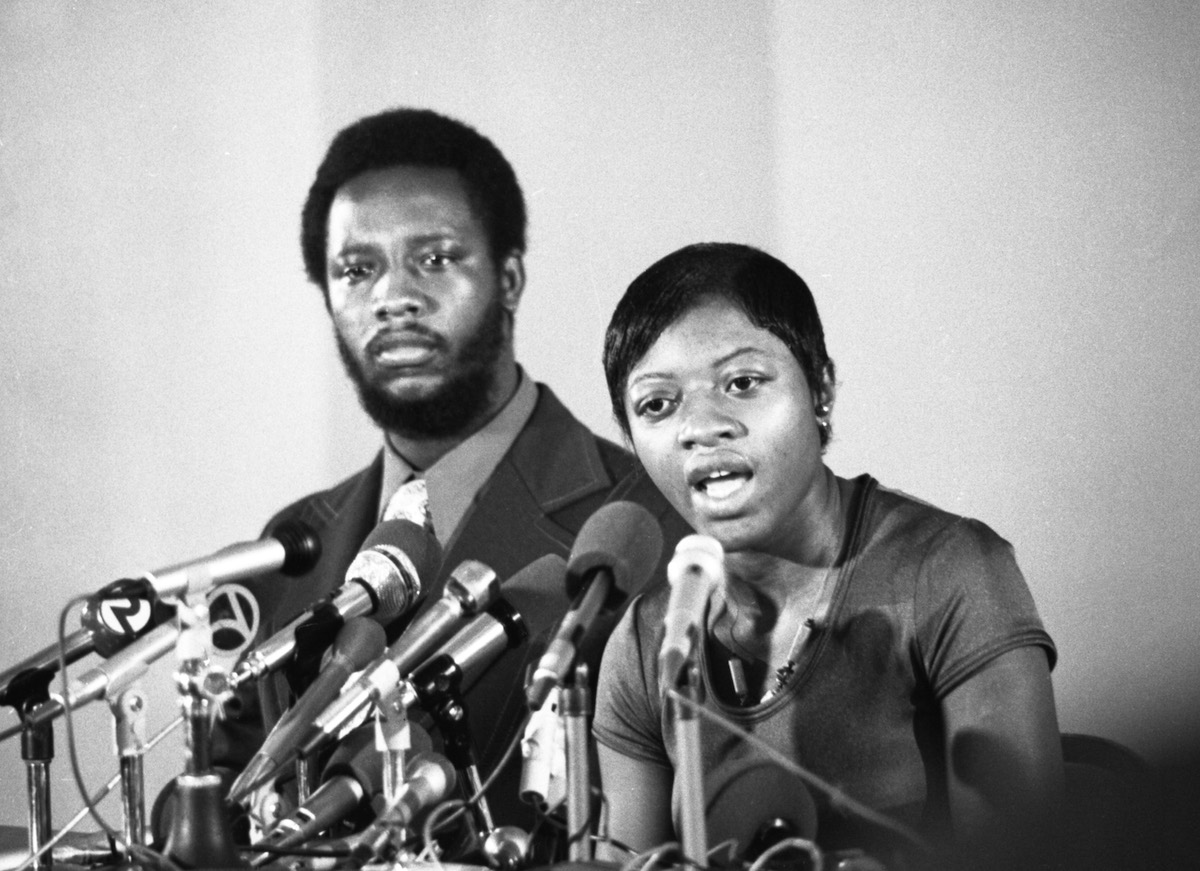

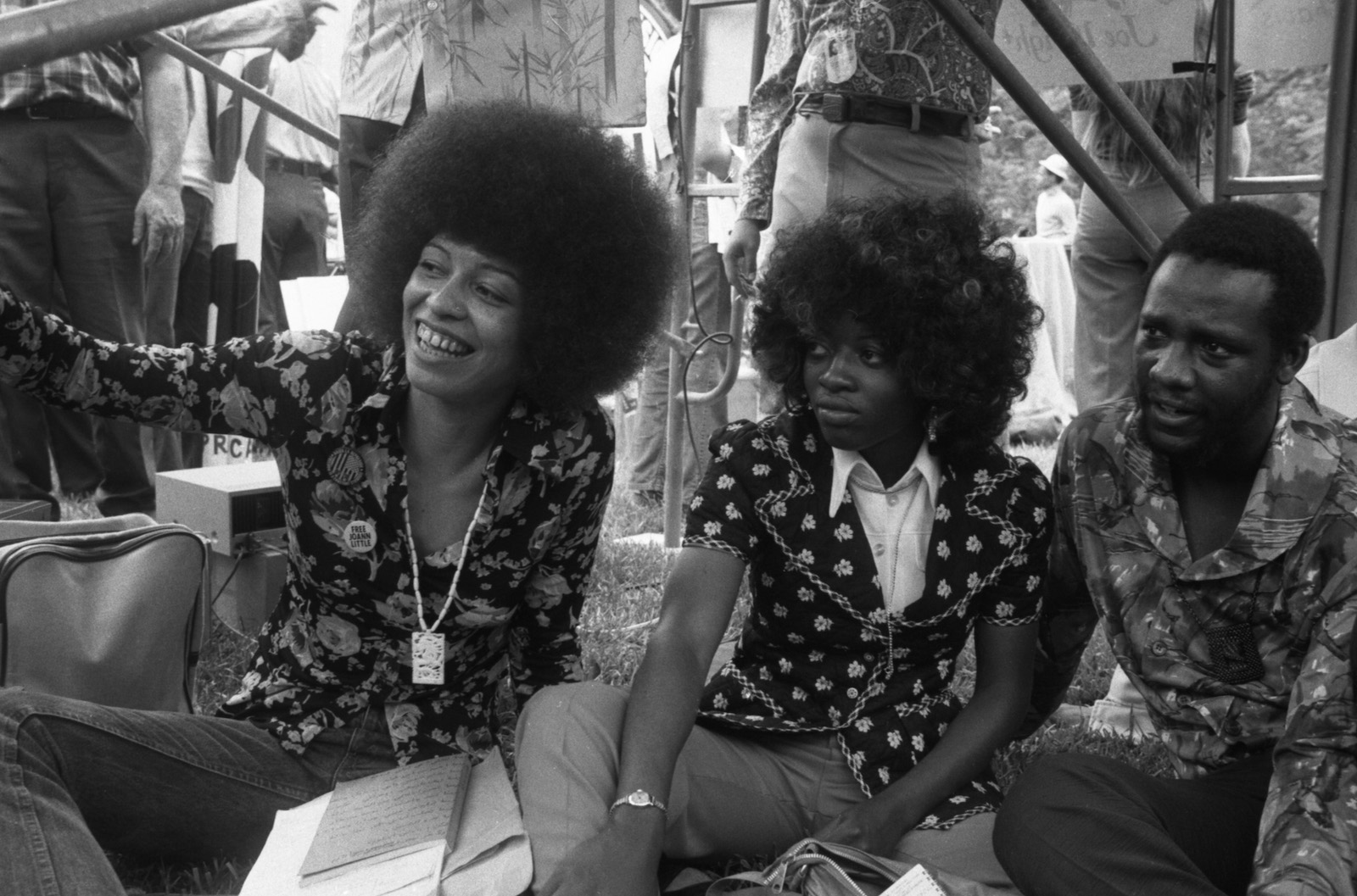

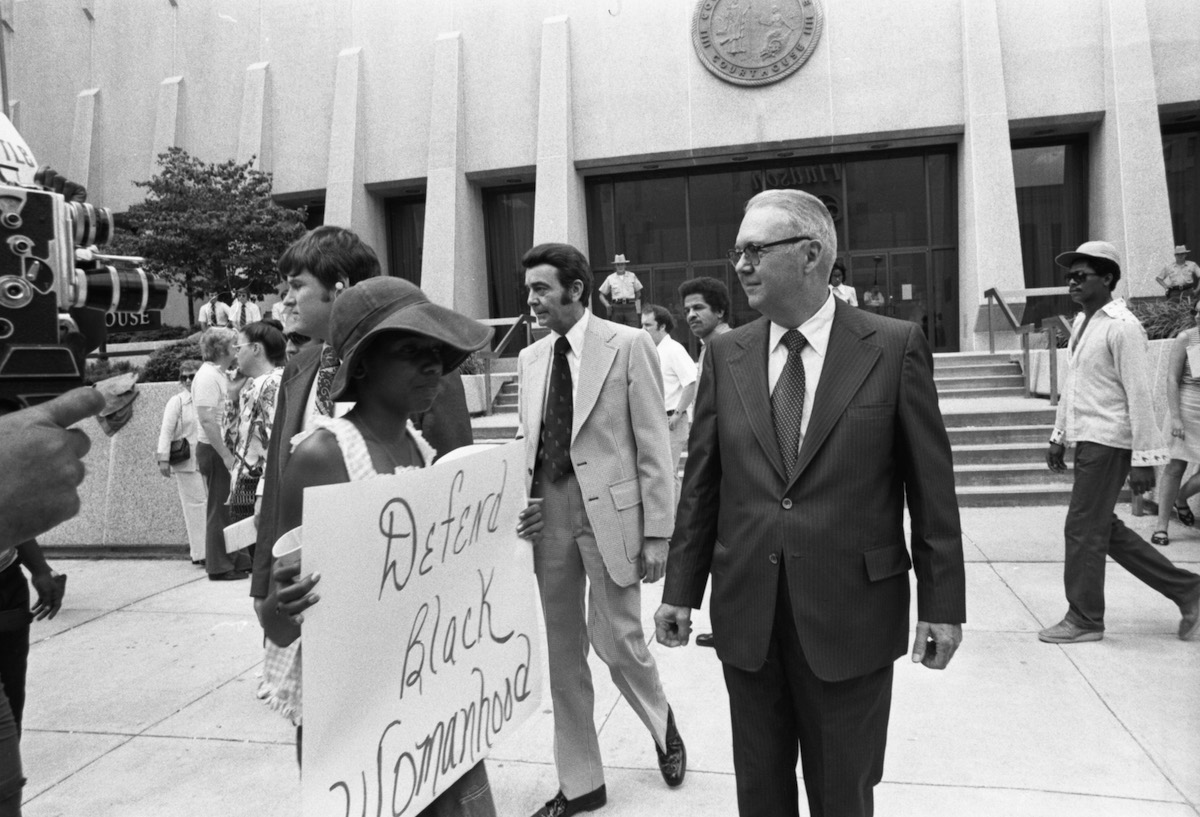

In 1975, Joan Little was on tour. Media covering the story of her legal case—a first-degree murder charge, her ultimate acquittal, and her subsequent retreat from public life—tended to frame her life as a political and social cause. Many groups took up her case as a landmark gesture toward prison abolition, antirape activism, and civil rights more broadly. She was—and remains—a cause célèbre for a generation of Black revolutionaries, making history as the first woman in the history of the United States to be acquitted of a murder charge with a defense predicated on using deadly force to resist sexual assault.

Little spoke at UNC-Chapel Hill in midsummer, a few months after making bond on February 26. She’d wanted to say just a few words—thanking her supporters, undoubtedly, as her trial loomed. But she also realized the importance of an audience for amplifying the needs of those she’d been incarcerated with just a few months prior. Little went on to outline the appalling conditions at Women’s Prison (formally the North Carolina Correctional Center for Women) in Raleigh: the grinding, everyday dehumanization of inmates, as well as specific abuses and instances of neglect. “The only way that they are going to put any kind of laws in there or change the kind of things they have in there now,” Little observed, “is that the people come together and demand that there be changes within those prisons, because those sisters are not living in there like they’re human beings.”

It is entirely likely that the talk at UNC was one of several invitations she accepted to speak on campuses. A New York Times article covering her August 1975 trial notes that a group of UNC professors raised the necessary $115,000 for her bond, securing her release and allowing her to attend several “Meet Joan Little” fetes where she “appear[ed] frightened and intimidated.” But we know this description to be false. That’s because we have the audio of her UNC-Chapel Hill appearance, accessible to the public for the first time here, thanks to UNC’s Southern Oral History Program. “Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights, and Black Power in the American South” is an oral history project, launched in 2011, that aims to understand the media and activism ecosystem of the American South during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. The project documents North Carolina’s many Black civil rights activists who thrived as journalists and broadcasters in independent and noncommercial media, featuring oral histories and rare and endangered sound recordings (now digitized) from stations like WAFR in Durham, the nation’s first public, community-run Black radio station. Little’s appearance at UNC was broadcast on WAFR, and we know of at least one other appearance on that station in 1975, when radio host Deborah Long interviewed her.1

The WAFR broadcast covers the shared inhumanity of incarceration and the urgency of liberation. Little’s case and cause resounded across the country and across the globe, but this recording highlights experiences grounded firmly in North Carolina. Little is out on bond, but she is mentally still in Women’s Prison. “I was an inmate,” she tells the crowd. “Now, I’m out here in society with all of you, and you look on me just like—like I’m a citizen. You don’t look at me as a person behind bars, with numbers, you know, across the chest. That’s why you can understand what I’m trying to say. I saw what these sisters were going through. I was there.”

Though we lack a precise date for this recording, context clues place Little’s talk within the immediate aftermath of the 1975 Women’s Prison strike. On June 15, 150 women prisoners refused to return to their dormitories when guards announced lockup at 8:00 p.m., gathering together to stage a peaceful sit-in on the grass of the prison yard. Supporters prepared to stay overnight on the outside of the fence. Their demands were wide ranging, though the most immediate catalyst for the demonstration seemed to be the appalling conditions in the laundry. In Dixie Be Damned: 300 Years of Insurrection in the American South, Saralee Stafford and Shirley Neal write:

The women were not just required to do NCCCW’s laundry but that of the entire State prison system . . . Balancing the budget apparently included forcing women to work in a 120-degree environment while handling tuberculosis-infected clothing with no safety equipment. The forced, unpaid, and dangerous work at the laundry compounded the larger institutionalized medical neglect at the prison. Reports from prisoners of this abuse were well documented, though typically ignored. Racial discrimination as well.2

Little described the significance of advocacy beyond prison walls: “I really feel that most of those sisters would have been, not only beaten, there would be a lot of them dead right now, because of the support that was outside of those gates the entire time the protest was going on, that was the reason why there were only as few injured as there were.”

This tracks with Safford and Neal’s documentation of the night of the sit-in, in which inmates were assaulted by prison guards and given group punishment:

According to one witness, “Others tried to help and were beaten. Once inside the gym, sounds of breaking glass, screams, and pounding noises could be heard.’ A prisoner later wrote, ‘The first blow was struck by the guard to a prisoner while on the front lawn. Others were carried by guards into the auditorium and thrown on top of one another.”3

Despite the guard’s retaliation, the inmates continued their protest, holding their ground until June 19. Dozens identified as ‘ringleaders’ were shipped to a men’s correctional facility, while more than fifty others were given additional time on their sentences combined with intimidation, solitary confinement, and denied parole. “You know that the sisters are going to be convicted,” Little tells the crowd gathered at UNC. “It’s going to be an undercover thing. And ain’t nobody gonna know about it but just the prison officials. That’s one reason why they cut off the communication. Because they don’t want the sisters to write out here and tell you what’s going on.”

In a zine published by inmates a year after the strike, Break de Chains of Legalized U.$. Slavery, produced in collaboration with the North Carolina Women’s Prison Book Project and the Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists Prison Book Project, the collected authors urged a consistent message of solidarity. “Unless a person has been confined and subjected to the cruel environment in which we live, it would be difficult for them to comprehend our reasons for wanting to be recognized as human beings and not animals in a cage,” wrote Anne C. Willett in a detailed examination of the events of the strike as she remembers them. “Keep us locked in, 24 hours a day, keep threatening us with sticks and tear gas, and keep thinking we will crawl to them, albeit, they will be the losers because from now on the toys will not move as they want them to. We have strong minds, deep determination and we will remain united in our struggle for justice.”4

Little is explicit with her gathered audience about the importance of genuine acts of solidarity from those outside of the prison system: “It’s not something that you can go home and forget. Because we’re out here . . . So I’m asking all of you, you know—this may be the last time that you even ever see me again. But one thing that I can say, is that regardless of how my trial comes out, regardless of however it comes out—I can say this: that I am going to leave behind those sisters, and it means that I have to lose my life, to prove to the people that everything the police says is not true, and everything that they do is not justifiable, then I feel that that is my right.” It is striking that this is the first time she mentions her own upcoming trial throughout her talk, at about eighteen minutes into the recording. Her appearance at UNC was an opportunity for her to raise consciousness about the pain and suffering happening just a few miles down the road at the North Carolina Correctional Center for Women—to underscore that every person incarcerated has a story, a voice, and a personhood worth defending.

Little’s appearance has modern-day comparisons: in 2016, UNC students hosted Cece McDonald, a Black trans activist who fought back against a racist mob that attacked her in 2011 outside of a nightclub. She was charged with murder and faced up to eighty years. “While in prison,” the event description read, “she discovered that her story was far from unique and that she was among many Black people, especially Black trans womyn, who had been railroaded into the prison system.” Similarly, in June 2021, Scalawag magazine republished excerpts of Anne C. Willett’s essay in Break De Chains alongside a letter from A. L. Harris, currently incarcerated at Pasquotank Correctional Institution in Pasquotank, North Carolina. “Scalawag publishes the account of A. L. Harris in honor of survivors of state violence and in memory of the lives of those harmed and killed by police,” the preface notes. “Bearing witness to the realities of those who were and still are incarcerated is the first step on the abolitionist journey this week. It cannot be the last.”

Joan Little retreated from public life in 1989, following a minor charge involving stolen vehicle plates. Her story is frequently flattened to some kind of flash in the pan, more important for legal history than for the administration of justice. This has lent itself to people attempting to “fill in the gaps.” A 1997 thesis out of the history department at UNC, titled “Remembering Joan Little: The Rise and Fall of a Mythical Black Woman,” underscores the degree to which scholars, writers, critics, and supporters alike projected their own beliefs about her guilt or innocence onto her life. Who gets to say that Little had a fall—or that she consented to being mythologized in the first place?

Little’s speech at UNC makes clear that she was not a lone figurehead. She was concerned with the lives of those who had walked similar paths—those who feared being forgotten behind prison walls, lost within a system designed not to rehabilitate, but to punish without oversight. Little knew that making the demands of those incarcerated known is one of the most powerful ways to exercise solidarity with those on the inside, to begin to chip away at our carceral system more broadly.

Little’s speech at UNC makes clear that she was not a lone figurehead. She was concerned with the lives of those who had walked similar paths.

Throughout its relatively brief existence, WAFR in Durham was something remarkable. A listener might have tuned in one night to hear Joan Little’s UNC broadcast, and an interview with a Black Panther the next. The Media and Movement archives offer a glimpse into North Carolina as a beating pulse of the Civil Rights Movement, utilizing a variety of mediums to elevate the voices of those on the front lines. As we approach the fiftieth anniversary of WAFR’s folding, with an expansive book on Joan Little forthcoming from historian Genna Rae McNeil, we can relish these recordings for what they are: not only primary sources of this history but ways of feeling the revolutionary presence of a woman committed to justice for herself and for so many others.

Transcript

This program was prerecorded for broadcast at this time.

I’m happy to be here. I hadn’t planned to talk very long, but since Celine told you everything that was going on . . . [and] sorta gave you insight into what was happening at Women’s Prison, I felt that it was very important that I, you know, spoke—rather than just saying a few words and then leaving. Because the thing, that Celine said, that’s happening in Women’s Prison is very important and it’s a serious matter. And I feel myself that if Celine, and other people, hadn’t been at the prison at the time those sisters were there protesting peacefully, as she said, trying only to get the changes that were necessary for them to feel that they were human beings and not as animals and as criminals, you know, that were locked behind bars—that the prison system felt that they were less than human. I felt—I really feel that most of those sisters would have been, not only beaten, there would be a lot of them dead right now, because of the support that was outside of those gates the entire time the protest was going on, that was the reason why there were only as few injured as there were.

In a way I understand a lot of things Celine is saying. Celine is an outsider, just like a lot of you. And, I don’t know whether any of you have ever been to prison before. I know a lot of you have been to jail. But being in jail is no way like being in prison. One reason I know is I spent six months in prison, over at Women’s Prison, same prison that those women are at now. And I spent six months in Dorm C, the same dorm that Marie Hill is in now. And Dorm C, let me tell you, is nothing to play with, because anybody who goes to Dorm C, whether they’re going there because they’re waiting for trial, or going there because they caused problems on the grounds, or whatever—the only time they get to come out of those cells are when they’re going to take a shower, or when they’re going to visit their relatives, or when they’re going to meet their attorneys or something like that. And they can always stop that whenever they get ready and there’s no investigation of why they keep you from seeing your parents or seeing anyone, for that matter. The only ones they have to let you see is your attorney. And when—from on the ground, and you’ve already been tried, and you’re doing fifteen, twenty years and life like Marie Hill, you don’t have an attorney. So therefore, you have to rely on the other inmates that are willing to stand with you for your rights or either you have to write outside, to let people on the outside know what’s going on. And that’s one reason why it was very important that Ralph Edwards [State Corrections Superintendent] cut out the communication within the prison. Because for a long time, while I was in there, I wrote to Celine myself, and as long as there are not any mail coming out of that prison, there’s not any phone calls coming out of that prison, it’s just like a wall set up so that they can just kill off those sisters anytime they get ready without anybody on the outside knowing it. And they know it. And the only way that they are going to put any kind of laws in there or change the kind of things they have in there now is that the people come together and demand that there be changes within those prisons, because those sisters are not living in there like they’re human beings.

The only way that they are going to put any kind of laws in there or change the kind of things they have in there now is that the people come together and demand that there be changes within those prisons, because those sisters are not living in there like they’re human beings.

I had God tell me—this wasn’t the first demonstration that was held in front of the prison, because I think it was in January that Celine and some other women supported the sisters about the same incident, the laundry, and Juanita Baker was there then. She gave them a permit to demonstrate in front of the laundry, you know, outside of the gates, protesting the condition of the laundry. Juanita Baker knew that the laundry was no place for women to be working in there, and they’re working eight hours a day with no kind of wages whatsoever. And so she knew what sisters were going through, and so she said, “Sure, you can come in, you can demonstrate.” Two weeks later, Juanita Baker was fired. And then they put it in the paper that she was neglecting her duties. It wasn’t because she was neglecting her duties, it was because she was superintendent of the prison, and she was standing with the inmates, and they couldn’t tolerate that kind of thing. So, they had to give rid of her. You see, this is coming from me, this is not coming from Celine, somebody that’s out here, that wrote her and told her about it. This is coming from an inmate. I was an inmate. Now, I’m out here in society with all of you, and you look on me just like—like I’m a citizen. You don’t look at me as a person behind bars, with numbers, you know, across the chest. That’s why you can understand what I’m trying to say. I saw what these sisters were going through. I was there. So, I don’t have to have anyone come to me and tell me, because I understand it.

You know, like, one instance—my attorneys came to see me one day and I was in the office, and when I came back, my mattress had been pulled out of the cell and was outside. And it had been ripped apart—all the cotton inside had been ripped out of my mattress. All my personal belongings was in the center of the floor. But yet that same night, they came to me, they wouldn’t give me a mattress or anything until I signed a sheet, I didn’t even know what the piece of paper was. But the lady told me, her name was Miss Violet, she said, “You sign this sheet or else.” I said, “I’m not gonna sign it. The only way I sign this piece of paper is if my attorneys see it.” She called in one of the lady sergeants on me, and tried to demand that I sign that sheet of paper. And I told her I still wasn’t going to sign it. So, I didn’t sign it, I took it and tore it up and threw it in the commode. She came back with another one, asked me what did I do with it, I told her I threw it in the commode because I wasn’t gonna sign it. The next week I found out that if I’d have signed that piece of paper, they could’ve brought charges against me. For what? Any kind of charges that they wanted to bring against me. And then, this same sheet that I could’ve, I had signed, could have kept me from gaining my bond for the first-degree murder charges, and I’d still be sitting in prison right now. But see I didn’t know this until later on, and see, these sheets, that they sign and they bring charges against you, they don’t take you to court. They don’t bring you outside so that people can see what’s going on, what they’re charging you with. They keep you inside the prisons, and like Celine said, they’re trying to bring charges against these sisters now, for inciting a riot—they’re not going to try them in a court outside here. They’re going to try them with the guards, with the superintendent, and with other people like Ralph and a few guards from Central Prison. And if they said these sisters are guilty, which you know they’re going to say they’re guilty, they can add two years onto their sentence, whether it be twenty years they already have, they can add ten years onto it, and they can add fifteen years onto it, and it’s perfectly legal, as they see it. Because of the fact the people out here, the public, doesn’t know anything about it. And see this is the type of thing that I’m saying, like Celine said that, Maria’s gonna be there until September, right? Okay, when they bring her in, they’re gonna have about ten people right up there at the administrative office, that are going to a room, and she has a right to a lawyer. You know who her lawyer is? She has a right to pick any guard, or any matron, from off their grounds, to be her lawyer.

Now this is what I’m talking about. And you know what they’re going to say. You know that the sisters are going to be convicted. You know that they’re gonna get those two years, they’re going to get those ten years, or fifteen years, they’re going to get that ain’t no doubt about it. Because of the fact that it’s going to be just like Watergate. It’s going to be an undercover thing. And ain’t nobody gonna know about it but just the prison officials. That’s one reason why they cut off the communication. Because they don’t want the sisters to write out here and tell you what’s going on. That’s the reason why they shipped them out. You know the ones that they shipped out? They shipped out the ones that they thought were influencing the other inmates. The ones that were the strongest. They shipped they out. But the ones that they knew they could control, that they could pacify by telling them that “we’re gonna keep you here, you know, but you gotta be real cool, because you know your parole is coming up, you know your honor grade is coming up, and if you promise us that you’re gonna stay in here and you’re not gonna defy us in any way, you can stay here.” Those are the sisters that they got there now. The ones they got in Wake County, the ones they got in Morganton, all of those sisters are the ones, like Coco. Coco, they’re doing fifty years for armed robbery. Marie here, I don’t know why they got her there now, you know, maybe it’s because she has a lot of influence on the inmates also, on the inside. And they know if they ship out everybody that is really strong, and they leave all those sisters in there, and just leave the ones that can be pacified, they know that sooner or later they gonna rebel against them.

They got sisters in there like Edna Bond. Edna Bond is doing like forty years, and they got people there, women there that are doing twenty, thirty, and forty years, and only seventeen years old. And then, they say, “Oh we’re just gonna send them to the Women’s Correctional Center, for rehabilitation, and for reform.” And then they put them—they either stash them in the laundry, in the dining room, and in the hospital. What do they have for them, you know, to make them want to reform and come back out here to live a life as a respectable person and not commit another crime and go back? They don’t have any schools that reform them—the girls—the only ones that can go to school are the ones that are about seventeen years old, eighteen years old, that are really young. They send them to school, and they only go for like one hour a day. And then, they have to work the rest of the eight hours. Now, that is not anything saying that is preparing them to come out here and get a decent job. Because 80 percent of the people out here now, are unemployed. And they don’t put something in there as a trade, to really give those girls some kind of basic thing to stand on when they come back out here in society. Then they don’t have anything to do but go back to the same thing that they were doing—right back to the same community and to the same friends that they were hanging around with. And nine times out of ten, like Ralph Edwards said, most of the inmates that come into the prison, they return again. But the question is—why do they return? Are they putting in anything in there for them not to return? And see this is what I’m trying to say. And then people—taxpayers are donating money, they’re donating clothing, books, and all this type of thing—but the inmates never see them. They got books there like Reader’s Digest that date as far back as 1939. I saw ’em myself [laughter, from Little and the crowd]. I saw ’em myself. And you know what I did with them? Nine times out of ten—it was a lady there, she’s on death row, her name is Rozell Hunt, she learned to read from those books. You know, because I cut out pictures, and made words, and put them there so that she could read them. She’s forty-five years old. And hasn’t even read a line in her whole life. She didn’t even know how to write her name, she didn’t know to spell her children’s names, or anything like that. And when I left, she knew how to read and she knew how to write. And she has blood clots on her brain, and they won’t give her any kind of medication, because of the fact that she’s on death row.

I went in there as a marshmallow, I was soft. When I came out, I came out as a bandit. I’m ready to strike back at them at any time. Because I saw what they were doing to those sisters.

People that are on death row get all—worse treatment than the people that are there doing twenty, thirty years. And they have to sit in the cell twenty-four hours a day. Now Rozell Hunt has been there four years. Mamie Ward has been there five years. Mamie Ward is just like a zombie, she just sits there. She doesn’t talk, she doesn’t speak, she doesn’t sing, she doesn’t do anything. All they do, constantly, is just pour this medicine into her, all the time. And you look at her, she open her mouth, her mouth is white all on the inside, where they drugged her up. Now if I’m lying, you ask Celine—Celine knows what’s going on in there. And this behavior medication thing—when you go over there and ask for treatments, whether it’s a toothache, a bellyache, a whatever—I went over there myself, you know, for an infection, myself—and you know what they gave me? Tylenols. That’s what they gave me. And I saw a sister over there, I don’t know what you call it—it’s something that you catch from shooting up drugs from somebody else’s needle—[person in the crowd shouts, “Hepatitis”] hepatitis—she had that, and from my understanding, she wasn’t even supposed to be in the cell with nobody. And they kept her in the cell, they didn’t send—they didn’t take her out of that cell, or take her to the hospital, and quarantine her, and give her any medication for that. She was in the cell right next to me. I was using the same shower she was using. You know, and they would bring in food and stuff in there, and all this kind of thing, the person that was in the cell with her, when they sat on the commode after her, they could’ve caught the same thing she caught. And there was a sister there with a toothache, and she laid there the whole weekend, with one little toothache, because they wouldn’t take her to the hospital. So, I don’t see any reason why they say these inmates are trying to incite a riot. If anybody is trying to incite a riot, it’s the police, as Celine said. Because they are giving the sisters a reason to strike back at them. They have been giving a reason to strike back at them. And they said that prison is for rehabilitation and reform, right? I went in there as a marshmallow, I was soft. When I came out, I came out as a bandit. I’m ready to strike back at them at any time. Because I saw what they were doing to those sisters, and I know that anytime that those sisters get ready to strike back at them, whether that means beating ’em, or shooting ’em, they’re not even supposed to have guns on those guards—they weren’t even supposed to hit those sisters. If they hit them, if the women hit the guards, they’re not even supposed to hit them back. The women are supposed to be able to press charges against those guards, right now, this very minute, right now. But they’re not going to be able to do that. You know why? Because they got them all shook down, they cut off all communication. They got them all stashed in Dorm C. And all those that are not stashed in Dorm C, they’re facing threats, you know, of not ever coming out. So, this thing is not something that you can laugh at. It’s not something that you can go home and forget. Because we’re out here. We can go home, we can drink wine, we can drink liquor, we can look at our TV, listen to the radio, and whatnot. But these sisters in here—they don’t even have the right to listen to the radio, look at the TV, or even sleep if they say they don’t have the right. Because as a matron told me, when you come in those gates, you leave your rights on the outside. So, I’m asking all of you, you know—this may be the last time that you even ever see me again. But one thing that I can say, is that regardless of how my trial comes out, regardless of however it comes out—I can say this: that I am going to leave behind those sisters, and it means that I have to lose my life, to prove to the people that everything the police says is not true, and everything that they do is not justifiable, then I feel that that is my right. [applause]

Learn more about the Southern Oral History Program’s Media and the Movement interviews.

Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler was an editorial fellow with Southern Cultures (2020–2021) and is a politics writer at the Jewish Women’s Archive. She holds an MA in Folklore and works in reproductive justice.NOTES

- Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights, and Black Power in the American South, accessed November 5, 2021, https://mediaandthemovement.unc.edu.

- Shirley, Neal, and Saralee Stafford. Dixie Be Damned: 300 Years of Insurrection in the American South. AK Press, 2015, 234.

- Neal and Stafford, 237.

- Break de Chains of Legalized U.$. Slavery (North Carolina Women’s Prison Book

Project, 1976), http://freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC510_scans/Prisons_Women/510.PrisonWomen.BreakdeChains.pdf, 5.