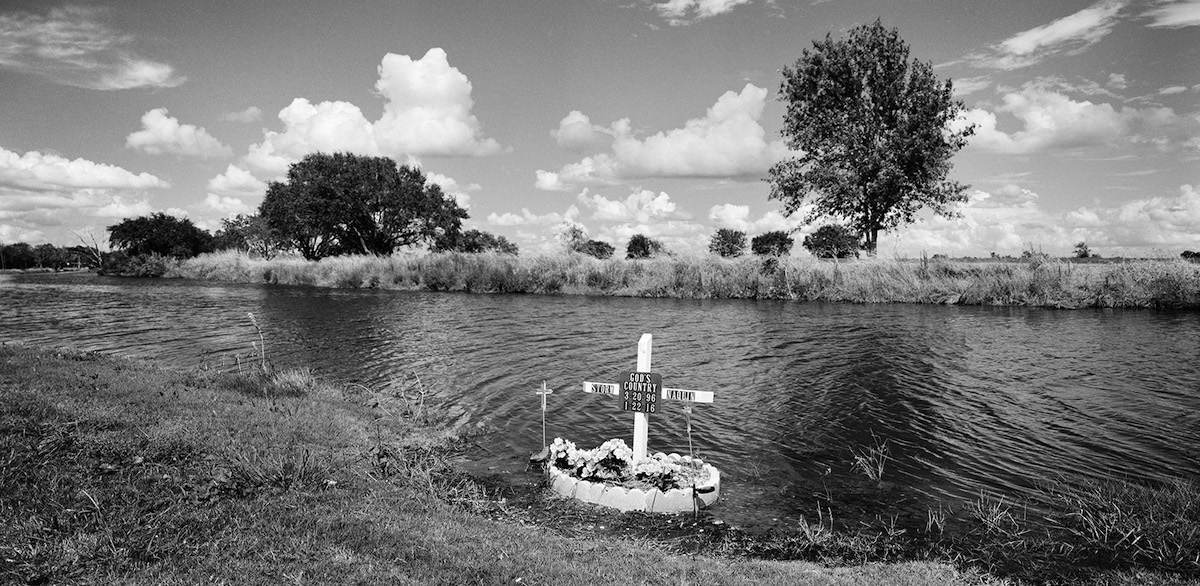

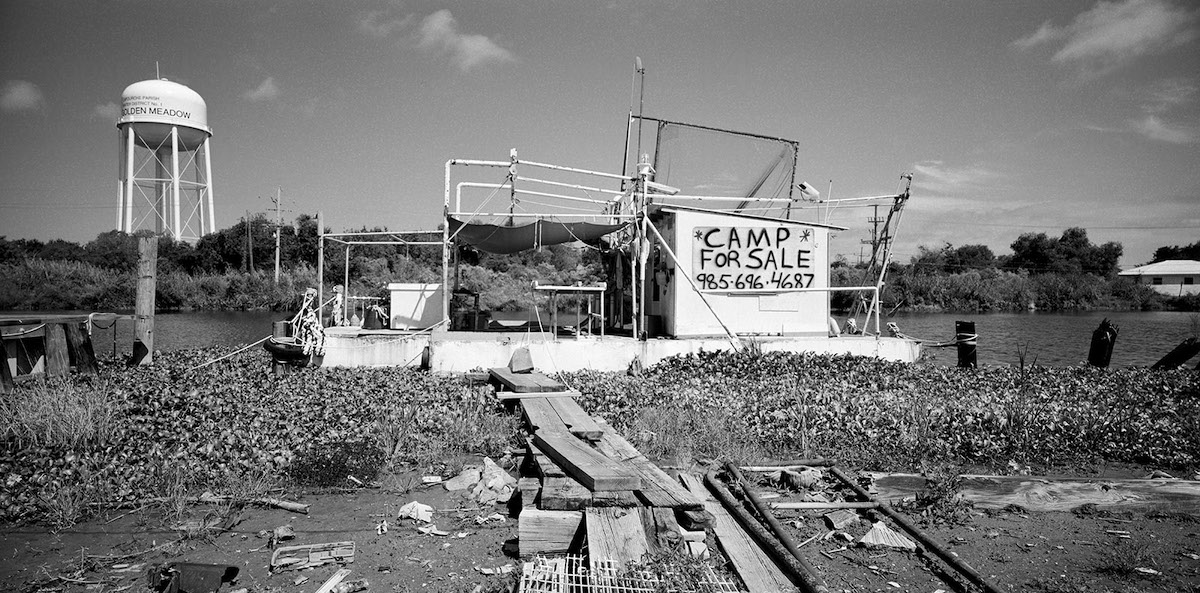

For the last few years, northward breezes have pushed more water from the Gulf onto the land—breaching marshes, overtopping the banks of bayous, and flooding roadways and people’s yards. Some of the submerged roads are the only ways in and out of narrow bayou-side communities strung along South Louisiana.

Louisiana is at the forefront of global sea-level change, experiencing the highest rate of coastal erosion in America, losing about one hundred yards of land every thirty minutes—land loss the size of a football field every half-hour. In addition to global sea level rise, in this century alone, a dozen major storms, including Katrina and Rita in 2005, and Ida in 2021, drastically changed the geography of Louisiana’s coast. This year has been the warmest year on record. And global temperature changes are only one of the factors contributing to the subsidence of Louisiana’s coast. Others include oil exploration, artificial channeling of wetlands, and even invasive species’ consumption of marshlands.

The barrier islands in Barataria Bay are some of the youngest and most unstable landforms on earth.

The barrier islands in Barataria Bay are some of the youngest and most unstable landforms on earth, averaging five thousand years in age, and they are rapidly changing shape and disappearing due to the man-altered flow of the Mississippi Delta. As an example, over the last century, Timbalier Island averaged a loss of twenty meters a year toward the northwest.

Coastal catastrophes certainly are not exclusively a phenomenon of the twenty-first century. During the early 1800s, some of the barrier islands served as summer resorts for wealthy New Orleans families. The Last Island, or Isle Dernière, was a popular resort for Louisiana’s upper crust, providing a regular steamer line, resort cottages, a village, and even a place to stay, John Muggah’s Ocean House Hotel. In 1856, a sudden category 4 or 5 storm split Isle Dernière, killing around two hundred of the vacationers and destroying every structure on the island. These events were described in Lafcadio Hearn’s novella Chita: A Memory of Last Island (1889):

Cottages began to rock. Some slid away from solid props upon which they rested. A chimney tumbled. Shutters were wrenched off; verandas demolished. Light roofs lifted, dropped again, and flapped into ruin. Trees bent their heads to the earth. And still the storm grew louder and blacker with every passing hour.

A few decades later, on October 2, 1893, an estimated category 4 hurricane struck South Louisiana’s barrier islands at the mouth of Barataria Bay. The community of Chenière Caminada was hit directly by a sixteen-foot storm surge that killed more than two thousand residents across the region and wiped the fishing village off the map. The Chenière Caminada hurricane remains one of the deadliest hurricanes in the history of the United States. Celebrated southern author Kate Chopin describes the life at Grand Isle and Chenière Caminada in her early feminist fiction Awakening (1899) and At Chenière Caminada (1894).

The physical disappearance of Louisiana’s coastline became a personal metaphor for the dissolution of my native Yugoslavia.

Since 1999, I have documented the endangered wetlands and dramatic changes in the landscape in South Louisiana. I emigrated from the former Yugoslavia to Louisiana at age 17 and attended Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, Louisiana. This project grew out of an annual photography and coastal ecology workshop created by my two college professors, who were interested in exploring the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary and building a partnership between the arts and sciences. First as an attendee of the workshop, and later as one of the instructors, I returned year after year to photograph the ever-changing landscape. The workshop ran successfully for 15 years, with support from the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) facility in Chauvin, Louisiana. After the conclusion of the workshop series, I continued returning to Louisiana every year to make my images and visit old friends in the community. The project originally started as an examination of the threatened coastline, and over the years became a chronicle of a location that is extremely important to the nation’s infrastructure and a culture that is central to the people who inhabit the land. While I did not realize that time would play such an important role in the series, it organically became one of the unique aspects of the work. I also realized that the physical disappearance of Louisiana’s coastline became a personal metaphor for the dissolution of my native Yugoslavia.

The series of images went through several iterations. At first, I used a traditional 35mm film camera and black & white film, but I eventually switched to larger format film. In 2006, after Hurricane Katrina, I designed and built my own pinhole camera, which took long exposures of the landscape through its tiny aperture. This allowed me to record longer segments of time, exploring the poetics of time passage. Several years later, I opted for the wide, panoramic image, composing photographs of the broad landscape with a format that emphasized the horizon. I continue to make images of the same locations, year after year. Buildings, trees, and cemeteries are anchors. This project is the longest undertaking of my career so far, chronicling the past two decades of continuously shifting landscapes and our adaptation to a new warmer and wetter world.

The town of Isle de Jean Charles is a historic home of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw people. The group settled in the area in the 1880s when the state started selling land legally to Indigenous people. The original four families grew to a group of sixteen families (seventy-seven individuals) by the 1910 census.

In the past sixty years, the community has lost over 98 percent of its land due to rising sea levels, hurricanes, and land subsidence. Within a generation, the island went from being five miles wide, covered with cypress groves and pastures, to a quarter-mile wide. In 2001, the Morganza Spillway was realigned, leaving Isle de Jean Charles out of the levee system and exposing the town to frequent coastal flooding and further hurricane damage. In 2016, the people of Isle de Jean Charles were awarded $48 million from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to fund their resettlement process. After many negotiations and setbacks, the Tribal Council accepted the HUD plan and funding to relocate to Schriever, Louisiana, about forty miles north.

Many have decided to stay, citing their inherent sovereignty, rights to self-determination, and cultural survival. Tribal members and leaders do not consider the project of resettlement successful. This process continues to affect more and more of the coastal population.

Daniel Kariko‘s work has been shown nationally and internationally in galleries and museums, including Noorderlicht Photofestival, Groeningen, The Netherlands; Edinburgh International Science Festival, UK; Rijeka Foto Festival, Croatia; and Photon Gallery, Vienna, Austria. Kariko’s work was featured in a number of online and printed publications, including Nature, Art Papers, CNN Photos, National Geographic Proof, and Discover Magazine.

Header image: Dead Cheniere, Highway 1, Louisiana