“Photographs in the South have reflected the patterns and vicissitudes of the weather, both climatic and social-political, throughout our history. And no region’s photographic tradition has been more engaged in, maybe even obsessed with, exploring and reflecting the injuries and scars of time—brought on more specifically by war, bondage, discrimination, class conflicts, and the ravages of nature, to name a few forces—than photography in the American South.”

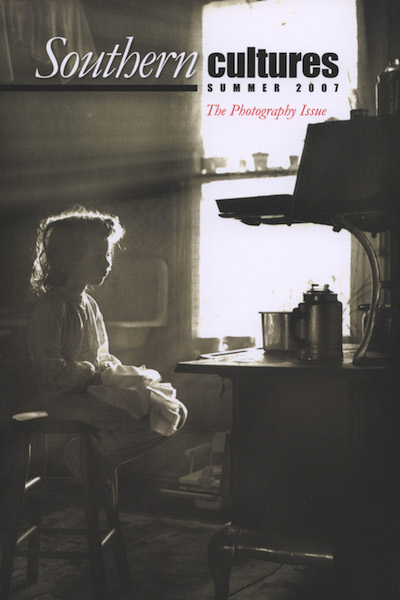

When I was a child I would take “forced” naps at my grandmother’s house on a daybed in a room on her second floor. Photographs covered the entire wall above me while I slept, and I well remember waking to first sight of unknown relatives, some in casual attire and others in more formal studio poses, parading across the wall in assorted sizes and frames. Most of the faces were unknown to me, appearing as wayfaring strangers in a family collection, unfamiliar in any way except that I’d seen the wall many times before. I knew the photographs but nothing of what they meant. My grandparents could point at the wall and talk endlessly about this person and that, the day the picture of my mother was taken, what happened to that tree my uncle was standing next to, which Sunday on which farm that picture comes from, the day the lightning struck that house, who this is and when that person lived. That wall was my first regular exposure to photographs, to what they mean to the people who made and have them, and to how the meanings shift over time and place and through the stories of different people.