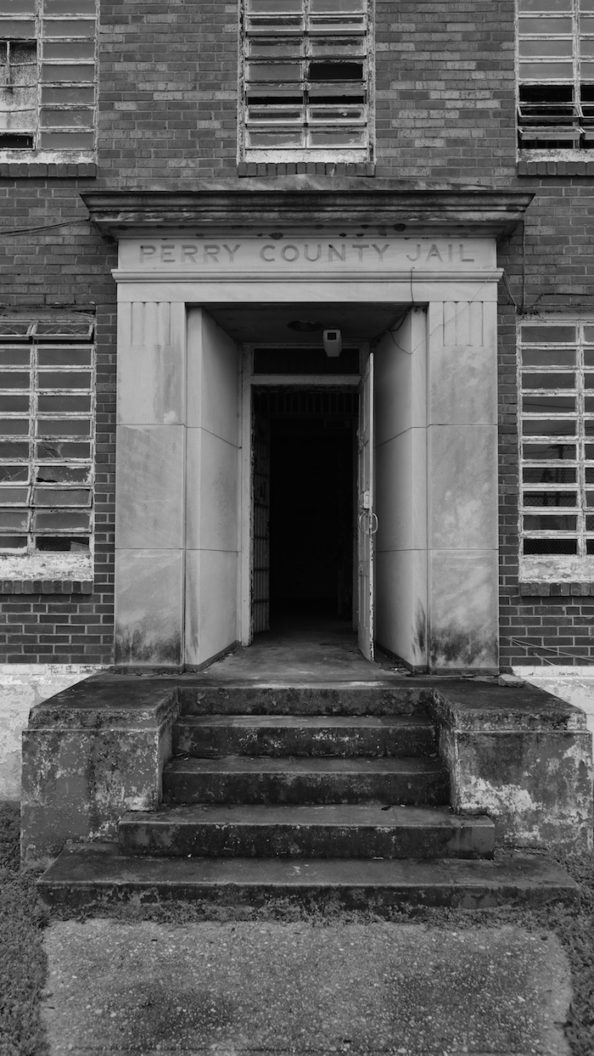

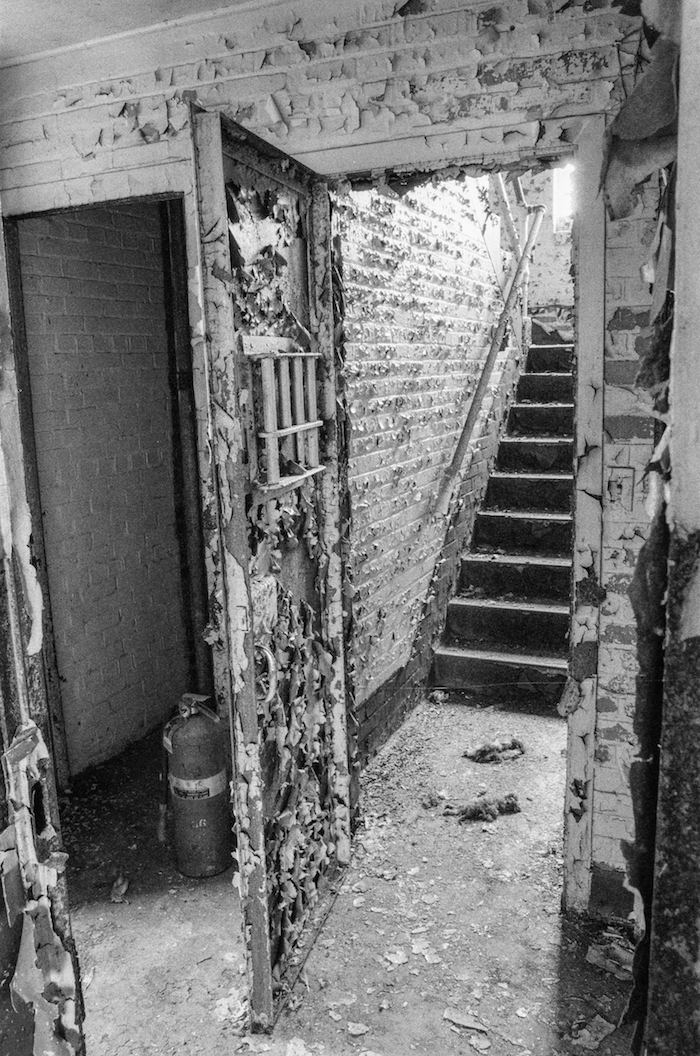

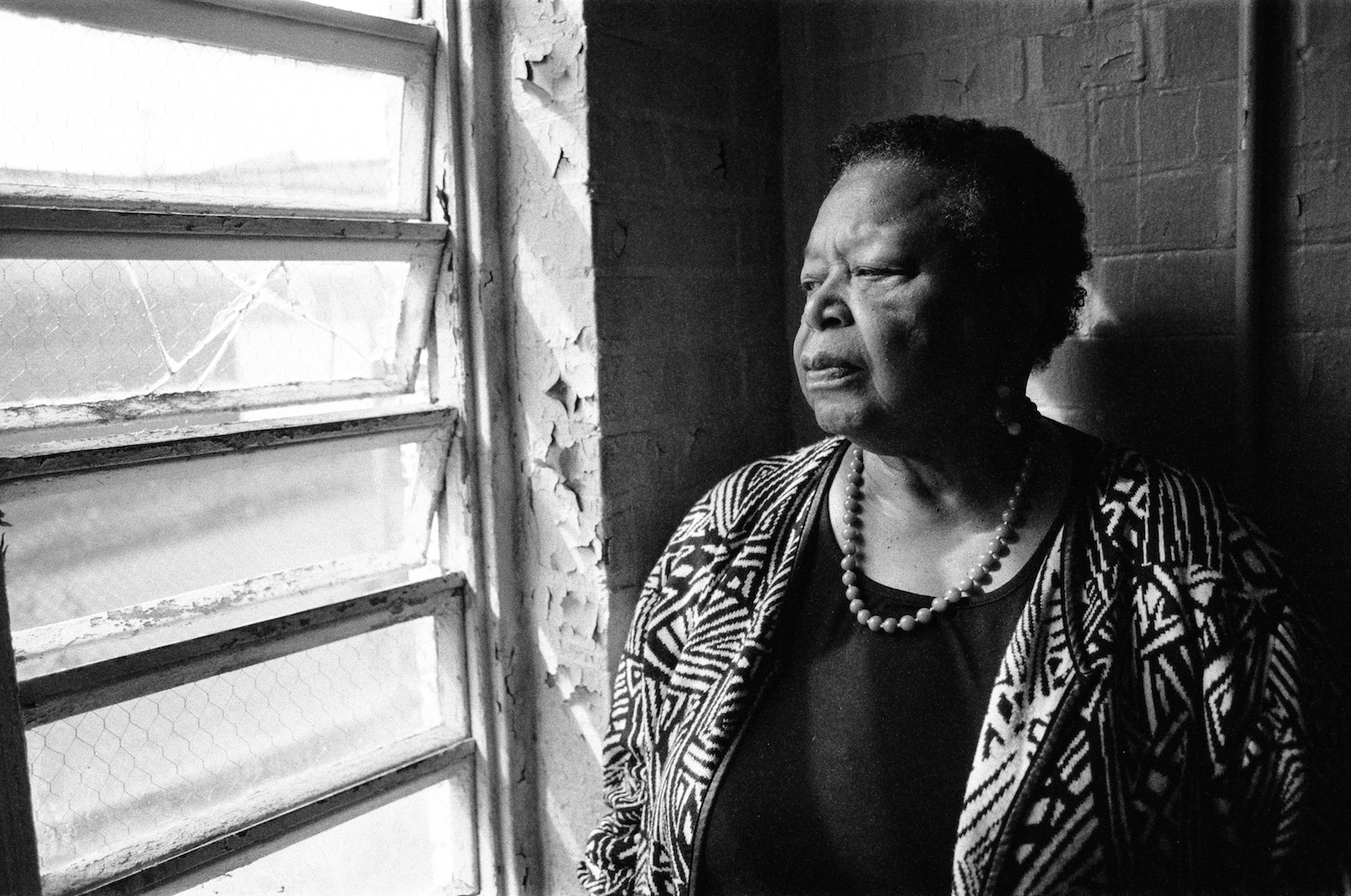

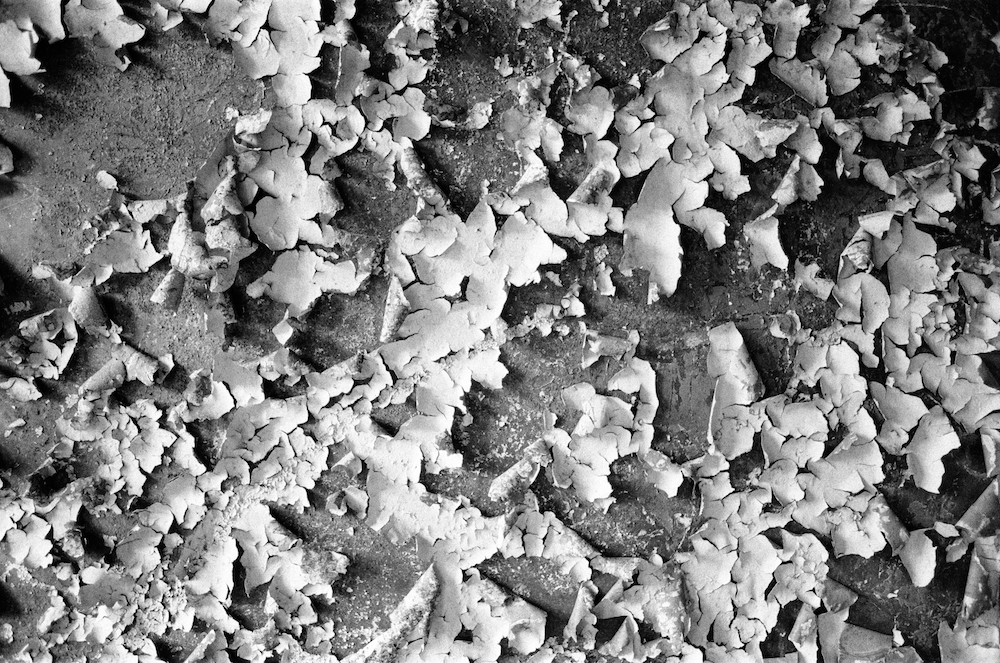

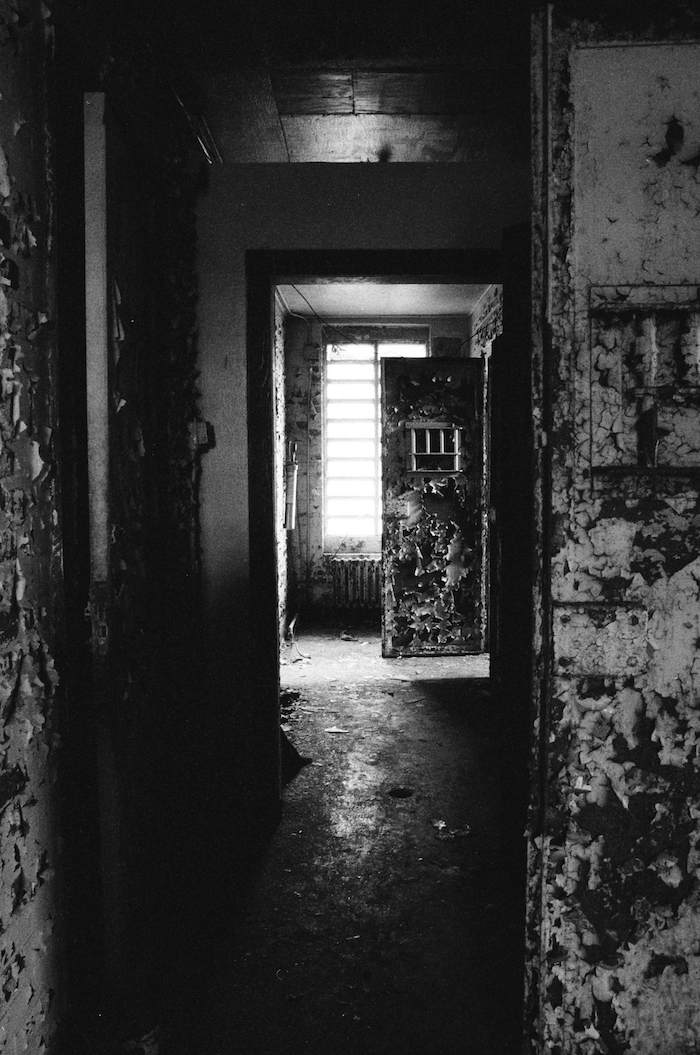

Peeling paint curls up from the walls in the corner of the Perry County Jail where Billie Jean Young stands, her hands hanging through the slim panes of a jalousie window. Prisoners used to hang their hands out like this, she tells me. “From outside, all you could see were hands.”

The jail has long been abandoned, and is showing it. The building has a story to tell, and Dr. Young wants to make sure it is passed on. While Selma is known for the famous marches that began there in 1965, those marches actually began in Marion one night in February, 1965, in the jail cell next to where Young tells me the story.

“Dr King sent people like James Orange and others here to the Black Belt to work with the youth, and that was the game changer,” Young says. Marion had long been a center of education in the Black Belt. In 1867, the American Missionary Association, along with the Freedmen’s Bureau, chartered the Lincoln Normal School in Marion for formerly enslaved African American students. Lincoln educated generations of Black Alabamians, including Coretta Scott King and Jean Childs Young, for over a century until its last class graduated in 1969. In the 1960s, it was fertile ground for recruiting Black students to the movement. Young explains:

James would come here from Greene County and Hale County, and he would go to those schools earlier, and get to Lincoln before noon, and those kids would be waiting for him. Sometimes they’d have demonstrations, march to some of the eateries that didn’t allow Black people to eat there, march downtown, or just march for the heck of it because they were mad that day, you know, about the conditions under which they lived.

Agents from the FBI and local law enforcement had been monitoring the movements in Marion and had targeted Orange for his civil rights work. On February 18, 1965, Orange led a march from Mount Zion United Methodist Church across the street to the county courthouse. Among the protestors were students from Lincoln. Orange was arrested for “disorderly conduct” and “contributing to the delinquency of minors,” and held in the Perry County Jail.

Later that night, marchers gathered at Zion to protest Orange’s detainment. Led by Albert Turner Sr., Rev. James Dobynes, and C. T. Vivian, the marchers processed down the block to the jail, singing and praying peacefully. Suddenly, the streetlights were turned off. In the darkness, Alabama state troopers, Marion police, and Perry County deputies began to billy club and pistol-whip protestors. They arrested some marchers and pressed others to return to the church, where police had blocked the front entrance. Forced to go around back, the protesters were met with more violence. During the chaos, local Baptist deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot in the stomach by trooper James Bonard Fowler. Jackson died in Selma eight days later. Fowler was finally indicted for second-degree murder forty-two years later. After years of delays, he pled guilty to second-degree manslaughter in 2010 and served five months of a six-month sentence.

Outrage over Jackson’s murder propelled the Selma-to-Montgomery Marches the month after Jackson’s death. An elderly local activist named Lucy Foster first proposed the idea of carrying Jackson’s body all the way to Montgomery and laying it at the doorstep of governor George Wallace. Eleven days after Jackson’s death, marchers, led by John Lewis, Hosea Williams, and Albert Turner, were met with a reprise of the state-sponsored violence at the Marion march, but on a much larger scale. A second march took place two days later, on “Turnaround Tuesday,” but did not proceed past the Edmund Pettus Bridge. On March 21, 1965, two weeks after Bloody Sunday, approximately 4,000 marchers crossed the Pettus Bridge under federal protection.

At the time, Young was two counties away in Choctaw County. Despite its proximity to Marion and Selma, Choctaw felt like a world away. “We had one TV station, and it was coming out of Mississippi. They would ‘snow’ the TV when news of the movement came on. Somehow, it just miraculously got snowed, so we didn’t hear too much about that was happening up right here, and I lived sixty-seven miles from Selma. There was no cable, there were few telephones, there was no Internet.” Young continues:

In ’65, I had just graduated high school and they would ask me, “What do y’all want? What is it you want?” I didn’t have any great answers because I wasn’t part of the Selma movement, but I knew that things weren’t that great for Black people in Choctaw County. I had spent most of my life in unaccredited schools. I went to a one-room school in Pennington—one teacher—until the sixth grade, and then I went to a school—Indian Springs High School—that had a set of encyclopedias for a library. So we were kind of cut off.

We didn’t have a lot, except that we had people who were much more together in a small town, that needed each other. So my daddy and other daddies provided the wood for the wood stove in our one-room school. Didn’t nobody have to ask them to do it, they knew when it was due, so they got the mules and the wagon and went and got the wood and brought it to the school. About once a year, the county gave us some coal and that was soon gone; after that, our parents had to provide. We walked three miles through the woods, home in the evenings. We’d catch a ride in the mornings with the high school truck. The county didn’t provide buses for us; it contracted with a local man, Mr. Tommy Bryant, and he would bring his pickup to pick up the school children. We walked home in the evenings through the woods, catching all kind of turtles and snakes, rabbits, all kind of things. It was an adventuresome time. And, of course, not having known any other, it was pleasant life. We had a good teacher, and she wanted us to learn. When she went away to Detroit in the summer to visit her son or to Tuskegee for a workshop, she would come back and tell us those things that she learned. Like telephone manners. Before we ever got a telephone or even had them in our community, she taught us telephone manners: how to answer [the] phone at home and take a message. She created fake phones for us out of cans and string. I don’t regret my childhood in the Black Belt. I was a happy child, learning.

From Choctaw County, Young landed in Selma shortly after the height of the marches. “I was working for one of the anti-poverty programs of President Johnson, working for a farmers’ co-op.” In 1965, leaders for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma—including Marion’s Albert Turner—proposed the idea of a farmers’ cooperative, which led in 1967 to the establishment of Southwest Alabama Farmers Cooperative Association (SWAFCA). Facing displacement and migration to northern cities, Black farmers found in SWAFCA a way to combine resources to keep their farms and assert their economic power. But it was not without resistance: when the Federal Office of Economic Opportunity awarded SWAFCA a substantial federal grant, the funding was blocked by Selma mayor Joe Smitherman and Alabama governor Lurleen Wallace, who tried to argue that the co-op was linked with Stokely Carmichael and “Black Power” movements in Alabama. Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) director R. Sargent Shriver overruled the governor, and SWAFCA became a model for Black economic development. It was also a turning point for Young. “It was the economic development aspect following the civil rights and voting rights protests of 1965, so I was working with many of the people at SWAFCA in Selma who had been directly involved in the movement. I caught the fire.”

Footsoldiers in Selma weren’t Young’s only encounter with the movement’s leadership. She says, “I met Dr. King when he came to Selma on the way to the Poor People’s Campaign. He came back to Selma just before he was killed.” King visited Young’s church, Tabernacle Baptist, in Selma in February 1968. “I didn’t wash my hand for the next day. We knew that we were in the presence of greatness. He didn’t have to die for us to know that. Dr. King walked in, it was like Christ.” Two months later, Young was in Atlanta for King’s funeral. “And that’s what hecklers were actually saying to us on the sidewalk: ‘Your black Jesus gone.’ In Atlanta, there were people there selling us Dr. King—selling us books and magazines, glossies had been created. And I learned that if you don’t chronicle your history, somebody else would do it for you, and do it quickly.”

Young’s time in the northeast opened her eyes to other disparities she hadn’t known in the South: “I found after the movement that whites in the South were more willing to listen to my complaints about their racism than they were in the North. Because the northerners didn’t understand it. Matter of fact, most northerners think all southerners are dumb, not just Black folks. I found that out when I went north.” One white southern law student at Boston College told Young that his experience in the north was the first time he felt equal to Blacks. Northerners, he told her, “don’t think I’m smart, either.”

In 1972, Young ended up in Marion as a student at Judson, and spent thirty years as an attorney, community organizer, poet, and playwright. In 2006, she returned to Judson, where she serves as associate professor of fine and performing arts and artist–in–residence. She has written three books, and plays about Fannie Lou Hamer and Jimmie Lee Jackson. The sense that many visitors have—that there is something different about Marion—drew Young back and keeps her here:

What I see in Marion is something many other Black Belt towns don’t have. It’s that same education that Dr. Potts was talking about. Education, to me, has been a saving grace for Marion and Perry County. Because you can only pull the wool so high over the eyes of a person who has knowledge in his head and can analyze and think beyond the immediate. That’s what I see in Marion.

What I also see in Marion, however, is a failure to reconcile itself to history on the part of all its people. I wish that Marion’s people, both Black and white, which are the predominant races here, I wish that we could learn how to treat each other as we would love to be treated and to be kind to one another. When I think about all I didn’t know at the time—lack of exposure—but my community didn’t have racism as a part of its history. But if you’ve been told that you’re better than other people all your life . . . you’re likely to believe it. And if you have been taught, by the same token, that you are less than, you’re going to believe that. And so there’s a lot of unlearning to go on.

The restoration of the Perry County Jail can, Young believes, facilitate that unlearning. “One of the purposes of this museum is to chronicle history here, so that a thinking person, a person with some analytical powers, will be able to come in here and see what life was like, to make their own decisions about whether or not a movement was needed, and whether or not it has helped us. I think the movement has helped us all in the sense that it has brought [this history] to the fore. It is out.”

Professor Young has a big vision for the site. Her campaign on behalf of the jail led to a $500,000 grant from the National Park Service in March 2018, which will help to fund the rehabilitation of the jail into a voting rights museum and theater space:

We plan within these walls to have a little black box theater so we can be able to show movement plays, things about the movement, as tour groups come. Part of my goal is to encourage young playwrights through contests and that kind of thing, and not just young playwrights but whoever wants to write, and we can stage them and have anywhere from thirty-five to forty seats. A town this size, and you can run something for a week or so and you’ve pretty much done it. I think this can also be an economic development tool for Marion. We want it to be a destination.

While Selma continues to attract national attention and regular visitors, Marion remains little known in the public imagination. But the Jail project could help restore Marion to its rightful place in the story of the Civil Rights Movement. “It is the first leg on the trail. . . . They had thought it was Selma, and Selma let them think that. But we are the first leg.” She goes on:

This is our home. And we want our children to be here. You know, we’re losing in the Black Belt. We are losing population. And when we lose the population, we lose so many resources [and] they go on and make other cities great, make other states great. I mean, some other people are doing great things in other places from the Deep South. The outmigration that went on until the ’70s is only beginning to reverse itself a little bit now. And while it’s great some of those people are coming back with resources, by and large, they are elders who have lived out their lives in the North. So we want to be able not only to have a place for them to come back to, but a place for our children to stay and work, and not have to leave.

Marion’s children, Young hopes, will have not just a place to call home, but a story to inhabit for themselves. “[I]f we can leave the story here for future generations, maybe they won’t have to cross this path again. We need to chronicle all of our history. You don’t write it down . . . it gets lost.”

The Perry County Jail’s story is a somber one, “but it is a history worth telling. A history worth preserving. And it is a precious history and this jail is precious to me for that reason because it was a place of infamy, and we can make it into a place of knowledge and understanding and hopefully some reconciliation.”

Watch an interview with Billie Jean Young

Pete Candler is a writer, photographer, and filmmaker based in Asheville, North Carolina. His work on memory and forgetfulness in the Deep South can be seen at adeepersouth.com