I was a tween when I first heard Lupe Fiasco’s “Kick, Push,” a song that describes the liberatory feeling soaring on skates provides. That song introduced me to the culture of Black street skating. During the summer of 2006, I took my hand-me-down pink-and-purple Barbie rollerblades and journeyed from my backyard to the neighboring cul-de-sac to try out my wings. After I outgrew those skates, nearly fifteen years passed until I got myself another pair. I started skating again while living in Texas with a crew of other neurodivergent and Black skaters.

Skating as an adult has brought me community in ways I hoped for and in ways unexpected. I have found kinship with other Black skaters and crip skaters, and intimacy with the urban landscape. I am a quad roller skater; I ride the same style of skates rocked by roller derby athletes and those rented out at roller rinks. I am also a disabled skater. The first year I skated as an adult was also the onset of my chronic illness and my autism diagnosis. But I found joy in rediscovering play in adulthood, with the state of Texas as my jungle gym.

Black skaters, and street skaters in particular, engage in the creative practice of reimagining cities. We see a staircase in a business park as the perfect place to practice 180-degree jumps. And we know we can add wax to a bicycle rack to make it slick enough to train grinds. As Black skaters, we uniquely reclaim our rights to public space through our skating and insist on our right to public joy. Our participation in this sport is a practice of critical geography, transforming our environments to experience the streets on our terms.

When I first started skating, I often caught myself looking for new ways to experience the city. On the bus to campus as a graduate student, I daydreamed. I would look out of the window and imagine I was skating along the sidewalks. I would visualize where I could jump, spin, and stall on the street obstacles. My routine commute to classes became a daily practice of creation, perceiving the urban landscape as a place of possibility.

I did not identify as disabled before I started skating. After the onset of my illness, skating was one of the few exercises I could do, and it quickly became the only exercise I wanted to do. Being autistic has given me a unique skating perspective and sensorial relationship to the city. I pay attention to the nuances in the pavement, learning to appreciate the even texture of asphalt roads and how to navigate cracked concrete. I roll with the gentle decline of streets that I am unable to notice when I walk. Autistic people have hyper- or hyposensitive nervous systems, and in my case, I feel everything under my feet. As I mentally map my neighborhood skate spots, I keep track of which pavement is the smoothest and what roads have potholes. While my hypersensitive body loathes bumpy roads, it deeply appreciates buttery smooth streets.

Street skating has also helped me embody a sense of economic geography. As I feel the contours of the street, I feel the inequality. The wealthier and gentrified neighborhoods in Austin have protected bike lanes, evenly leveled asphalt, and even the luxury of sidewalks. In predominantly Black neighborhoods, the roads are more often pothole-ridden, uneven, or neglected.

The summer I purchased my adult skates, I was desperate for other skate companions. Overcome with excitement, I spent my vacation days watching skate tutorials online and reading skate blogs from around the world. I successfully convinced my sister and brother-in-law to get skates as well, and we enjoyed rolling together. But my hyperfixation was insatiable. I yearned to be immersed in my new passion, and my desire far exceeded that of my neurotypical family members. I took my skates on a trip to visit my family for a few weeks before heading to complete my master’s fieldwork in Santo Domingo (where I also had my wheels). While my siblings worked their office jobs, I felt alone and bored in my childhood neighborhood, so I searched for skating companionship online.

Skating-related hashtags on Instagram led me to the collective African Rollerblading Diary. Its founder, Daniel Ogbogu, is a Lagos-based Nigerian skater dedicated to connecting Black skaters around the world, regardless of skill level. His mission is to invest in skating communities in Africa. And through the African Rollerblading Diary, he highlights skaters and their ability to manipulate and create within a built environment. Roller skaters soar over stacked tires and discarded wooden pallets, creating obstacles for themselves to demonstrate their skill. One video features a skater jumping over a set of stairs and riding perpendicularly to the wall, their legs floating in the air above a potted plant before arriving firmly back on land. Another clip shows Nigerian skaters balancing their blades on bike racks, then doing 360-degree spins over traffic barricades. Until happening upon the African Rollerblading Diary, I had never seen so many Black skaters. But now I have a virtual crew to share my progress with and get tips and ideas from.

Through the 1960s, roller rinks were segregated spaces and Black skaters were permitted only on certain nights. While this allowed Black skaters to develop their distinct style of skating, it prohibited Black access to the wider skate culture. White rinks and skaters discriminated against Black skate styles and aesthetics. During the 1960s, many Black skaters used small, low-to-the-ground wheels, which rink managers often prohibited due to fear they would scratch the floors. These wheels rolled easily, giving Black skaters the mobility and control they needed for their skating styles, which emphasized complex footwork and choreography. Because of segregation and discrimination, many Black skate communities were forced to transition to skate outdoors. Decades later, the culture and style Black skaters developed in rinks has been retained and expanded, with Black skaters participating in dance skating and aggressive street skating.1

Police violence and anti-Black racism make street skating a precarious activity for Black people. I fear being stopped by the police or racist civilians when I skate around my neighborhood. I know I might be targeted for skating too fast and being seen as a threat, or for simply being happy outside. Street skating is a radical act for Black skaters in reclaiming our rights to public space and public joy. Through play, we choose to boost our hypervisibility and subvert anti-Black geographies.

While skating in my neighborhoods over the years, I have met many young girls who compliment my skates. It fills me with joy to show children, especially Black children, that they have access to public spaces for the sake of pleasure and happiness. As part of a Black skating community, I assert my rights through sick grinds and gnarly airs. In the US South and the Global South, we are here shredding and making space for ourselves.

This essay was published in the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 2: Summer 2023).

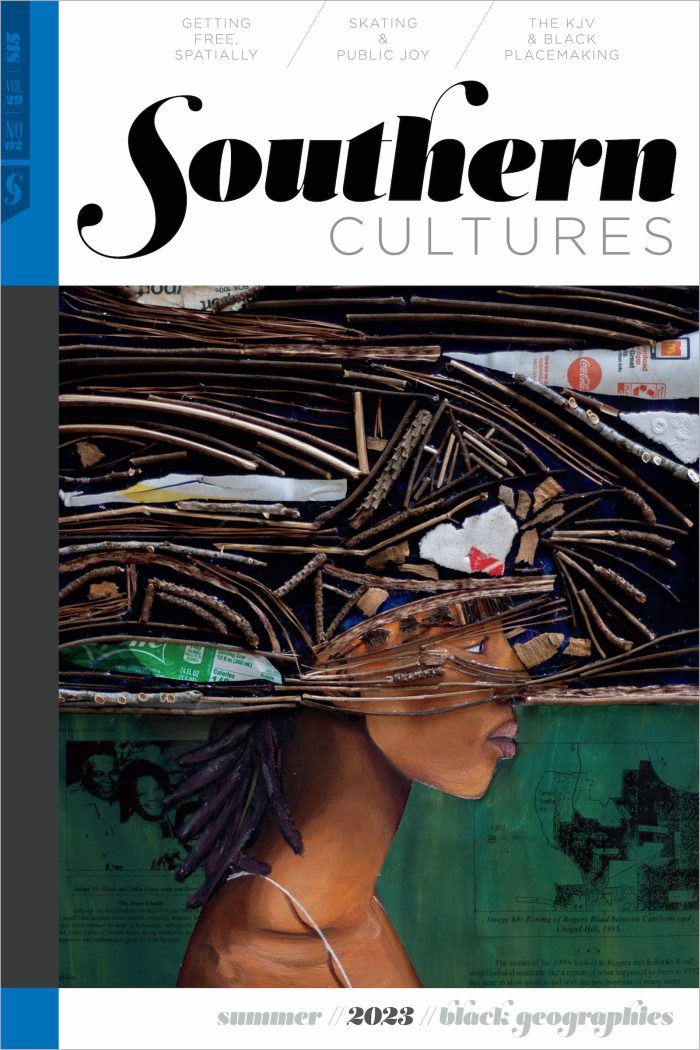

Suzanne Nimoh is a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas at Austin.Header image: The author wears blue roller skates, black knee pads, and rainbow socks with the word “TEXAS” repeated on them. She has dark skin and she is in a school parking lot skating toward a dumpster and jumping over an orange traffic cone. Photo by Joshua Reason, Austin, Texas, 2020.

NOTES

- Makeda Easter, October 6, 2020, “How learning to roller skate helped me connect with a piece of L.A. Black culture,” Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-10-26/how-learning-to-roller-skate-helped-me-connect-with-l-a-black-culture. African-American Roller-Skate Museum, n.d., “Black Culture and Roller Skating: A Historical Timeline,” accessed July 9, 2022, https://www.afamrollerskatemuseum.org. Many rinks continue the practice of prohibiting small wheels. Moonlight Rollerway in California, for example, lists “no mini, micro, or fiberglass wheels” under the rules section on its website. Moonlight Rollerway, n.d., “Dress Code, Code of Conduct and Safety Rules,” accessed July 9, 2022, https://moonlightrollerway.com/dress-code-code-of-conduct-and-safety-rules/.