The air inside my red and white cooler was still warm from the car and the sun when I opened it on the kitchen counter. I stuck my face inside and inhaled fresh-picked figs from Virginia’s Eastern Shore. They smelled grassy and sweet, of caramel with just a touch of sour. The fruit—grape-sized to large as lemons—was mostly intact, but a few were crushed, their finely speckled skins bruised and oozing milky white sap.

I picked this bounty hours earlier in Bernard L. Herman’s living library of fig trees at his home in Machipongo. I sliced a few open, pausing to admire their complex interiors. And because I had way too many of this tender and fleeting flower we know as fruit, I prepped the rest to make jam another day.1

Herman is a scholar-farmer (of vegetables, fruits, and oysters) deeply committed to regional specificity, who has written extensively about Eastern Shore foodways. He cultivates his own land and water and works to connect local producers with chefs on the mainland. In 2017, he helped establish the Eastern Shore of Virginia Foodways group “devoted to sustainable and culturally meaningful economic development on the Eastern Shore,” with the mission of “one job for one person so one family doesn’t have to leave.” At the group’s most recent fundraising meal in October, A South You Never Ate (named for his 2019 book), Herman put it simply: “This place is who I am.”

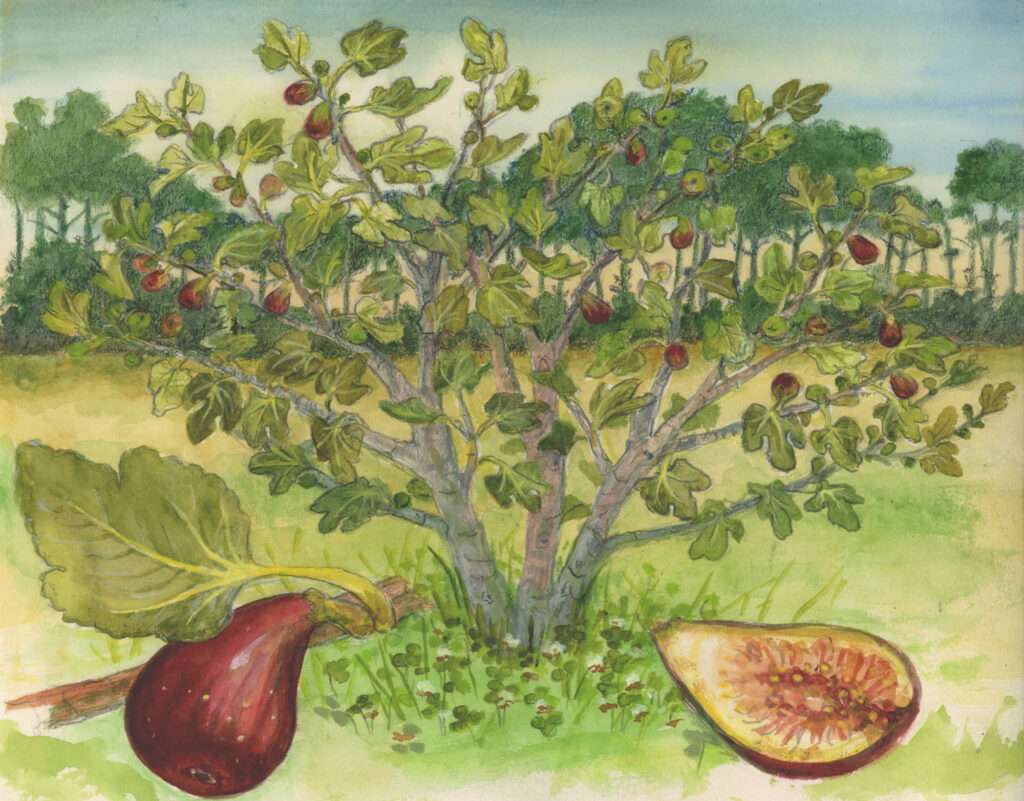

In 2003, a year after Herman and his wife Becky returned to the Shore after decades away, he began to collect local varieties of fig trees. This living library now includes roughly thirty trees, protected by a wind-breaking line of pines. The trees are planted in pairs, enjoy eastern and southern exposure, and thrive with no maintenance. Regional specificity in this collection is at the micro level—Herman’s fig trees are named for the people and places from which they were foraged (always with permission). As Herman believes, figs “sing the song” of the Eastern Shore, of regional food, identity, and belonging.

As his former student and now Virginia’s state folklorist, I’m fortunate to call Herman one of my mentors. He helped me see and write about the world with care and intention that grows from a deep respect for the subject—an abstract sort of skill which, for better or worse, has become part of my life’s work.

In graduate school, on a bus ride together, he convinced me to write about Laotian foodways while I was still nervously holding onto other, safer-seeming ideas. His crucial encouragement was balanced by the challenge to improve. I endured a mind-stretching writing seminar, facing Herman across his desk alongside only one other student. By the end of the semester, we were closer friends and better writers.

That was a decade ago, and in the last two years, I have had the pleasure of visiting Herman at home in Machipongo three times. I’ve seen a different side of him there. He is as generous with vittles as he is with his teaching. He will put on his waders to harvest and cut open an oyster for you, invite you to chase it with a beer from the fridge in his shed, and send you home with a handful of local heritage seeds and a few jars of preserves (smoked eels, whole figs, mincemeat). If Becky is home, you will probably leave with sweets, too.

This spring, Herman kindly allowed me to interview him about his work and about his figs. I went back again in August to visit the fig trees at their ripest, and entered an orchard transformed, this time loud with birds and insects. As I introduce four fig varieties in Herman’s library, I am reminded of the lessons I’ve learned from their cultivator-librarian-chef. If we can attune our attention to subtle differences and develop skills, including listening with respect, a world of living libraries opens around us.

I. Westerhouse Fig

Two of the largest trees in Herman’s library are Westerhouse figs. Westerhouse leaves are broad and dark green, with figs that are yellow-ish and crazed when ripe. Inside, they are glistening pink, with countless interior petals each ending in a tiny seed.

“It has a real complex flavor profile,” says Herman. “I’ll take the new leaves and a bonefish, with herbs, lemon, and ginger, and wrap it and steam them.” Herman also smokes Westerhouse fig leaves, then grinds them up and puts them in spice jars. “They are excellent in holiday cookies.”

This fig is named so because Herman discovered it along an old fence line on his property on Westerhouse Creek, just two inlets (or creeks) south from where he was raised. Nearby is the Pear Cottage fig and the lucky Home Depot fig, which he rescued from a dumpster.

Naming is a way to respect and remember. The Hooksie Walker fig is for Herman’s friend, former owner of the Bayford Oyster House, one of the only remaining shucking operations on the Shore. After Walker died, Herman says, “I asked Phyllis Walker if I could take some cuttings and get them started to give them to some of Hooksie’s old friends.” The cuttings Herman planted are now thriving. “When Hooksie passed away, he was in his 90s,” Herman says. “He died in the same house where he was born, overlooking Nassawadox Creek. He remembered playing under those figs as a little kid. And now I’ve got two of them.”

Reflecting on why he wrote his book A South You Never Ate, Herman said, “I thought, what could I do that might be of use to this place? What I do is write in respect, and that’s what I wanted to do here.”

Writing with respect takes great care and attention to detail, to the differences that define particular people, places—and figs.

II. Princess Anne Fig

Lime green and nicely round when ripe, the Princess Anne fig is ruby red on the inside. Herman collected this stunner from Terry Thomas, owner of a nursery in Princess Anne, Maryland, the northern part of the peninsula.

“Figs have a shelf-life of about a nanosecond,” says Herman. This means the figs abundant across the Southeast have never been a product of the market—they are too fleeting and fragile and stand outside of mass production. Near the Princess Anne grows the Farmer’s Delight, or Goffigon Fig, a fool’s errand. It was cultivated during the Great Depression in hopes it would sell for a fortune in New York, but the fruit could not survive the train ride.

An abundance of delicate ripe figs challenges one to call on one’s communities. Herman’s figs represent networks of branching relationships, tended to with care. His library yields a stunning harvest, so much so he is in discussion with Richmond’s Virago Spirits about delivering 2,400 pounds for a special seasonal fig brandy. When he can’t keep up with the harvest, he shares with friends, among them William Baines, who will pick and sell figs in his roadside store, Baines Farm and Market.

What you can’t eat fresh, you must preserve. “Princess Anne figs are really good for preserves,” says Herman. The most common way to put up figs on the Shore is to can them whole in spiced sweet syrup. Herman also makes pickles with still-hard, unripe figs, vinegar, and spices “gentle” enough to not overwhelm delicate figgy flavor.

Fig History

Native to Asia, the fig (Ficus carica) came to the Americas in 1520, imported by the Spaniards to Hispaniola, five years before the plant made its way to England from Italy. Captain John Smith noted its existence in Virginia by 1621, the cultivar having been transplanted from Bermuda. Jane Pierce of Jamestown was the fig’s first Anglo-American devotee, harvesting one hundred bushels in 1629, an amount that suggests the presence of a sizable orchard and preservation endeavor. By the early eighteenth century the cultivar had run feral.

—Bernard L. Herman,

A South You Never Ate

III. Hog Island Fig

Figs are native to the Mediterranean and arrived in the United States in Spanish hands in the sixteenth century. Cultivated for millennia for their fruit, figs are in fact inverted flowers, containers for tiny interior seeds. Hundreds of varieties of Smyrna figs evolved side-by-side wasps perfectly suited to crawl inside to pollinate (and perish in the process). Common figs (ficus carica) do not require pollination and instead are best propagated by rooting clippings. In the South, it is people like Herman—swapping, sharing, and planting rooted branches—who introduce figs to new places.2

There is no fig more time-consuming to harvest than the small Hog Island fig, or as locals call them, sugar figs. “To pick any meaningful amount is a lot of work,” says Herman. “They are no bigger than the top joint of your thumb,” but they are ideal for preserves. Herman also sautés them with garden jalapeños. “The balance of flavors is just terrific.”

Herman collected his first Hog Island fig clippings from outside the life-saving station on the now-uninhabited barrier island. The small, super sweet variety was in vogue at the turn of the last century, when hunting clubs on the Shore hosted well-heeled dignitaries. So in demand were they that Hog Island figs were served to President Grover Cleveland in 1892, as part of a Thanksgiving feast before his second inauguration.

Perhaps more than any other in Herman’s collection, these distinct little figs belie the human hands that cultivated them on the island and then ensured their survival on the Shore. “I’ve come to really appreciate that we are present in our work and we should make ourselves visible,” says Herman. “Not in excess, but to ensure our presence is there and acknowledge it.”

IV. Brunswick Fig

The Brunswick fig is large and tear-shaped, with a deep caramel-burgundy bottom that lightens as it reaches its green tip. Inside it is pale pink, and it is so large, there is a cavity, a secret interior. This fig is a favored variety in the Southeast and it has an intense flavor that makes it good for drying.

“This would be the fig I would make a Fig Newton with,” says Herman. “It is really quite spectacular.” Herman also cuts massive figs like the Brunswick in half, puts gorgonzola in the middle, and grills them, topping them off with a small bay leaf and a dash of black pepper. “People seem to like that,” he says.

To Herman, a fig is an object that invites us to interpret its significance through conversation, and then attempt to communicate that significance to others. It is a way of seeing the world. This is the folklore method, and as Herman teaches, it is best used in service to the “well-being and the good of the community.”

“If your purpose is serious enough,” says Herman—if you consider the fig for the songs it sings—you may check out a clipping from his library and begin your own living collection. Of the four clippings I took home in June, one Hog Island fig has taken root. I hope I can keep it going long enough to plant. I’ve come to believe that a fig library is a sort of a mandate for a good life. For attention to subtle differences and the seasons, to the resilience of a single plant over time, to how to use what is around you for pleasure and for sharing, to be generous, to save things for later, to take care of your community. To pass it on.

Figgy Newmans

Albemarle Baking Company | Charlottesville, Virginia

Reprinted with permission from Jennifer Lapidus, Southern Ground: Reclaiming Flavor Through Stone-Milled Flour (Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed, 2021). Gerry Newman, who co-owns Albemarle Baking Company, developed this recipe using dried Hog Island figs from Bernie Herman.

YIELD: 10 COOKIES (OR 20 IF CUT SMALLER)

DOUGH

302g (2¾ cups) Trinity Blend flour (or your own blend)

5g (1 tablespoon) baking powder

½ teaspoon fine sea salt

150g (⅔ cup) unsalted butter, at room temperature

120g (⅔ cup) granulated sugar

3 eggs, separated, at room temperature

50g (¼ cup) heavy cream, at room temperature

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

FIG FILLING

90g (⅓ cup + 1 tablespoon) water

150g (1 cup) dried figs, quartered

35g (3 tablespoons) granulated sugar

1½ teaspoons lemon zest

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

- In a medium bowl, combine the flour, baking powder, and salt.

- In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter and sugar on medium-high speed until light in color, 5 to 10 minutes. Adjust to low speed and add the egg yolks, cream, and vanilla, then increase speed and mix until creamy and fluffy, then stop and scrape down the bowl.

- With the mixer on low speed, add the flour mixture and mix until the ingredients are fully incorporated and a dough has formed. (This dough is very rich, so there is little danger of overtaxing.) Turn the dough out, wrap it in plastic wrap, and refrigerate until thoroughly chilled.

- Meanwhile, make the filling: In a medium saucepan, bring the water to a boil over medium-high heat. Add the figs and the sugar, cover, and reduce the heat to maintain a low simmer. Cook until most of the water has been absorbed, then remove from the heat. Allow to cool for 10 to 15 minutes and then transfer the mixture to a food processor, add the lemon zest and juice, and process to a smooth paste.

- Cut two pieces of parchment paper the size of a baking sheet. Place the dough on one piece and lay the second piece eon top. Roll out the dough between the two sheets of parchment to a 15 x 18-inch rectangle. Remove the top piece of parchment and cut the dough in half lengthwise to make two 4-inch-wide strips. Pipe (or spread) the filling lengthwise along the center of one strip of dough, then fold the long sides of the dough in so they meet in the center and enclose the filling, gently pinching the edges together to seal. Repeat to fill the second strip of dough. Refrigerate the logs of dough for 30 minutes.

- Preheat the oven to 325°F. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

- Turn the filled logs of dough seam-side down and cut them crosswise into 2-inch wide cookies. Transfer the cookies to the prepared baking sheet. Lightly whisk the egg whites to make an egg wash and brush it over the cookies.

- Bake for 25 to 30 minutes, or until nicely browned and then transfer to a cooling rack. Allow to cool for 20 to 30 minutes before serving. Once full cooked, store in an airtight container at room temperature.

Katy Clune is Virginia’s state folklorist and director of the Virginia Folklife Program of Virginia Humanities. She earned a BA in art history from UC Berkeley and an MA in folklore from UNC Chapel Hill. Raised in the Foreign Service, she has called six countries and both US coasts home and now lives in Charlottesville, Virginia. She has interviewed marine diesel engine mechanics, Buddhist monks, luthiers, chefs, and many other folks. See more of her work at katyclune.com.

Designer Miriam Riggs’s subject matter is largely derived from the native flora and fauna of the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Much of the work is functional, such as floorcloths, painted furniture, and jewelry. Over the past fifteen years, she has also researched and developed exhibits for the Barrier Islands Center in Machipongo, Virginia, and managed the extensive restoration of an Historic Landmark Eastern Shore house. She holds a degree in studio art from Old Dominion University and is a founding member of the Eastern Shore of Virginia Artisans Guild. She has been a self-supporting craftsperson for 50 years and works from her studio on a property near the edge of Onancock Creek.

NOTES

- The quotations included in this piece (unless otherwise noted) are from the following oral history interviews: Interview with Bernard Herman by Katy Clune for the Virginia Folklife Program of Virginia Humanities, Machipongo, Virginia, April 28, 2024; Interview with Bernard Herman by Katy Clune (other participants Ayşe Erginer, Irene Newman, Emily Wallace) for the Virginia Folklife Program of Virginia Humanities, Machipongo, Virginia, June 14, 2024.

- Britannica, s.v. “Fig wasp,” accessed November 20, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/animal/fig-wasp; In 1899, two species of fig wasps were introduced to California where they are still used for pollination in commercial agriculture. For more on fig propagation and figs in California, see the University of California at Davis Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center guide, https://ucanr.edu/sites/btfnp/fruitnutproduction/Fig; Contrary to popular belief, the fruits of common fig do not require internal pollination by a specialized wasp. The fruits of Ficus carica are parthenocarpic (fruit develops without fertilization) and therefore do not require multiple cultivars to set fruit. As fruits mature, look for three signs of ripeness: color change from green to brown or purple, softened fruit and hanging fruit. Celeste Scott, The State Botanical Garden of Tennessee, “Common Fig: Ficus carica,” accessed December 3, 2024, https://utgardens.tennessee.edu/common-fig-ficus-carica/#:~:text=The%20fruits%20of%20Ficus%20carica,softened%20fruit%20and%20hanging%20fruit.