It can be an odd undertaking to explore the meaning and mission of an American public university through the lens of history. The concept of a “university of the people”—especially for a southern state university—must begin with a great and unyielding asterisk.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was all male until 1897, when a tiny handful of women were admitted. Female enrollment had increased to only four hundred by 1940. By 1962, women constituted 22 percent of the student body. They moved from the periphery only in 1972, with the passage of Title IX of the Higher Education Act.1

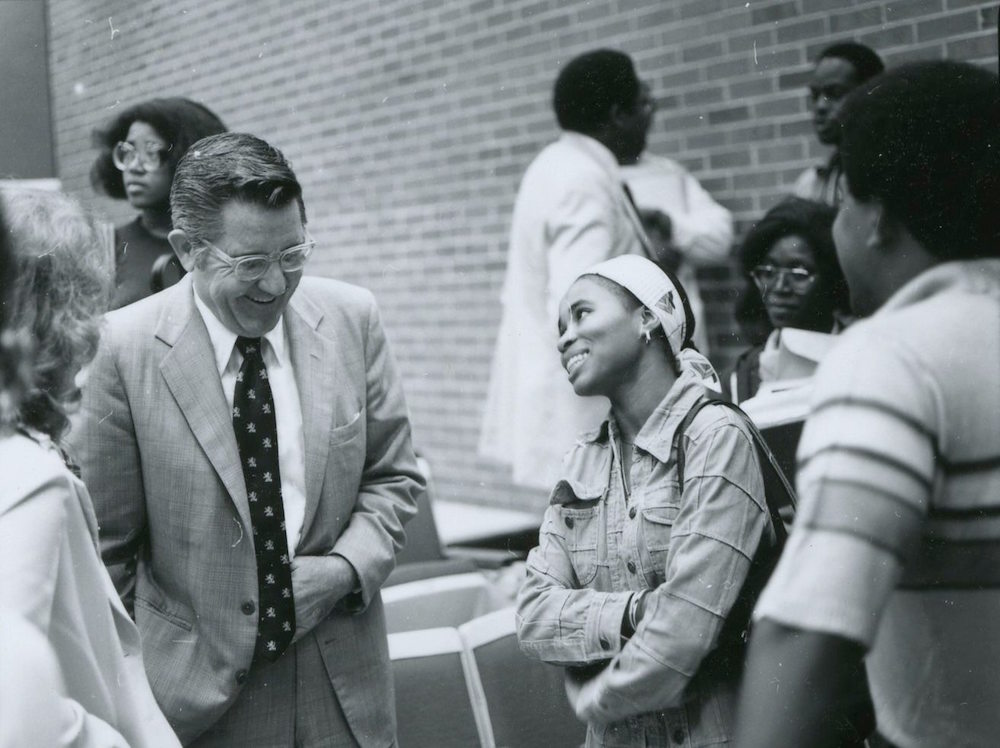

The federal courts ordered the admission of African Americans to UNC’s School of Law with McKissick v. Carmichael in 1951. The first three black undergraduates were admitted in 1955, after Brown v. Board of Education was handed down a year earlier. Enrollment of black students remained exceedingly low for many years. In 1960, four black students entered Chapel Hill. Only eighteen were enrolled in 1963.2

Like many institutions, in other words, the University of North Carolina’s embrace of equal protection was almost nonexistent for the bulk of its history and that breach dramatically wounded the prospects of the state, the school, and Carolina’s most vulnerable people. Nor, accordingly, could it accurately raise the banner of a people’s institution. Silent Sam is not our only transgression.

Still, Carolina has much to teach about the mission of public universities. It was, of course, the nation’s first state university. It carries the mark of William Davie, Edward Kidder Graham, Howard Odum, Frank Porter Graham, William Friday, William Aycock, and a cadre of other remarkable leaders. The New Republic would write, by 1936, that “North Carolina [had] become the leading institution of higher learning in the south.” John Egerton, in his masterwork Speak Now Against the Day, writing of the 1940s and ’50s, concluded that “the single most glaring exception to the broad-based mediocrity of the southern academic world was the University of North Carolina.” For more than two centuries, North Carolinians have spent energy, talent, and character to build a flagship university as a public good. Progress has hardly proven linear, but it’s been more than significant.3

This essay has two broad goals. The first is congenial. It uses the history of the University of North Carolina to suggest what the central purposes and challenges of a great state university should be. Issues of access to the empowerment of extraordinary learning and research, service to the most challenging needs of the commonwealth, assistance in the meaningful implementation of democratic norms, and the effective safeguarding of academic freedom and independent governance constitute the main focus. Carolina’s story, even briefly phrased, speaks to them all.

The second aim is less pleasant. Over the last decade, I’ll claim, the University of North Carolina has done much to abandon the cornerstones of its long-shouldered sense of public obligation. Commitments to economic access, uplift of the marginalized, the skeptical exploration of public policy, and the rigors of free exploration and independent accountability have been notably eroded. It is always disheartening to see a vital institution lose its way. But, as Carolina plunges, it also betrays a set of commitments that has long served as a lodestar for state universities across the country. Losing Carolina debases a set of noted values—central to the defining mission and meaning of great publics—that have marked both the institution itself and its leadership position in American higher education. Losing Carolina matters.

On Public Obligation

North Carolina’s first constitution called for the creation of a state university. It spoke of subsidized teacher salaries “allowing professors to instruct at low prices” (Article 41). A statute chartering the university itself was enacted in December 1789—fittingly, only a few days after the state ratified the U.S. Constitution. UNC’s principal founder, William Davie, believed that “only through the establishment of first class academies and a state university could the self-government and liberty attained through the revolution be preserved.” Davie, historians report, saw the new school, erected in the woods of Chapel Hill, “primarily as a vehicle for training public leaders, politicians and servants of the state.” It would open doors purposefully for those who could not overcome the economic barriers inherent in private education.4

A post–Civil War constitutional provision codified the sentiment: “The General Assembly shall provide that the benefits of the University of North Carolina, as far as practicable, be extended to the people free of expense” (Article IX, Section 9). Frank Porter Graham, UNC’s most famous and consequential president (1930–1949), offered a charge in his inaugural address “to build in this region one of the great intellectual and spiritual centers of the world for even the poorest youth.” Former UNC president C. D. Spangler (1986–1997), who passed away in 2018, saw low tuition as so vital that he had the phrase “Article IX, Section 9” etched into his official portrait.5

A democracy of the student body, though, has not been seen as the only component of an engaged public university. Edward Kidder Graham (1914–1918) thought it essential that a public university embrace the Progressive Era notion of the mind in service to society. He described UNC’s campus boundaries as extending to the borders of the state—and implored Tar Heels to “send us your problems.” Graham urged his academic colleagues to escape the “cloister” and “release the educational principles and scholarly ideals of the university into channels of service” so that it would become an “instrument of democracy for realizing the high and healthful aspirations of the state.” Journalist Jonathan Daniels would write, in the mid-twentieth century: “The university grew in stature by getting down closer to the earth and . . . examining the human qualities of the state and the south.”6

That required a particular focus, in Frank Graham’s words, “on the plight of the unorganized and inarticulate, unvoiced millions.” Howard Odum, perhaps the university’s most defining scholar, controversially explored appalling conditions of poverty, farm tenancy, cotton culture, and rural illiteracy “to expose the facts, encourage reform, smooth social change, [and] make democracy effective in the unequal places.” President William Friday (1956–1986) would be even more direct in his focus, calling it crucial “to turn the university’s mighty engines loose on the lacerating issue of poverty in North Carolina.” Friday regularly reminded students that “a million Tar Heels living in poverty pay taxes to subsidize your tuition; you need to think about what you’re going to do to pay them back.”7

Carolina’s leaders have also attested that, if a vibrant democracy cannot exist without powerful and effective public universities, vibrant state universities cannot exist without an equal commitment to the values and processes of democratic liberty. So long as public universities are funded and controlled by legislatures, they’ll be uniquely subject to political tampering. A robust and renewed commitment to academic independence is thus essential. Frank Graham, again, claimed, “[W]ithout freedom there can be neither culture, nor democracy; without freedom there can be no university.” Academic liberty, he wrote, “means the freedom of the scholar to report the truth honestly without interference by the university, the state, or any interest whatsoever.”8

To Graham, “the freedom to think, freedom to speak, and freedom to print are the cornerstone and motto of the first American university to open its doors in the name of the people.” When, in 1936, trustees moved to fire English professor E. E. Erickson for dining at a Durham hotel with a black NAACP leader, Graham responded, “[I]f Professor Erickson has to go on the charge of eating with another human being, then I’ll have to go first.”9

When Graham was blasted for allowing controversial speakers in Chapel Hill—and particularly when he defended the pathbreaking but heavily criticized work of scholars and institutions like Odum and UNC Press—he responded, “I owe it to the great traditions of this university to take the blows as they come and [I will] as long as it is my responsibility to hold fast to principles [of liberty].” Graham echoed earlier sentiments voiced by President Harry Chase when, in 1925, the General Assembly threatened academic freedom by proffering an anti-evolution bill. Chase told a legislative hearing, “If it be treason to oppose the bill offered in the name of tyranny over the mind, I stand here in the name of progress and make my protest.” When he was reminded that UNC’s appropriation stood in the balance, Chase responded, “[I]f the university doesn’t stand for anything but appropriations, I don’t care to be connected with it.”10

The 1963 Speaker Ban Law, which prevented purported communists from speaking on campus, represented UNC’s greatest ever challenge to academic freedom. Chancellor William B. Aycock, in response, defiantly stumped the state by demanding repeal. He said bluntly, “It would be far better to close the doors of the university than to let a cancer eat away at the spirit of inquiry and learning.” He issued an urgent national call as well:

Generation after generation have gone forth from this campus to provide sound leadership throughout the length and breadth of the land. It is a pity so many have left us for other places. We need them now. The University of North Carolina has come a long way fathered by rebellion and mothered by freedom. We may be short on cash, but we’re long on freedom.11

Newspapers across the state carried Aycock’s bold speeches with banner headlines such as “Chancellor Looses Searing Blast at Speaker Gag Law.” Legislative leaders responded with anger. Senator Adam Whitley of Smithfield told reporters he’d had enough “big talk from the Chancellor.” Whitley said,

I am sick of hearing university leaders praise the Legislature out of one side of their mouth for giving them the money they asked for, and, out of the other side of their mouth, criticize us for passing a law approved by the great majority of people. The Legislature has the authority to direct how state institutions are run and we need no assistance from Mr. Aycock.

Chancellor Aycock, in response, raised the stakes. He said, in a speech to the state’s legal community:

Even more surprising is the constant admonition directed to those few of us who speak out that we should be quiet. This brings a new dimension to our representative form of government. There is nothing in the history of this State or Nation to support the notion that the merits of legislation cannot be discussed in full measure. Neither the decisions of presidents, governors, congress, the General Assembly, or the courts, both state and federal, have ever enjoyed the immunity suggested for this legislation.12

In 2002, the year following the 9/11 attacks, UNC-Chapel Hill selected Michael Sells’s book, Approaching the Qur’an, as its Summer Reading Program offering. The choice provoked protests, lawsuits, and threats of budget cuts from the General Assembly. Chancellor James Moeser refused to cancel the selection, citing a Chapel Hill history of academic freedom and inquiry rooted in the legacies of Graham, Friday, and Aycock. Such giants, Moeser claimed, teach that “we have a moral responsibility to our state and our nation as a public university to bring to the public square the great issues of the day without fear of censorship.” Carolina’s success, Moeser argued, was tied to a deep tradition of intellectual independence and accountability, a defining “moral compass.” Accordingly, he would not overturn the controversial assignment.13

Rejecting a Legacy

UNC Chancellor Robert House (1945–1957), speaking of Graham’s imprint, said that in Chapel Hill the great values of academic integrity and independence are “caught, not taught.” If House was right, the last decade has shown that administrators often no longer successfully complete the reception. Commitments to access, democratic exploration, social critique, service to the powerless, and academic independence and integrity are in frightened retreat. The reversals pose a growing threat to North Carolina’s greatest intellectual asset and one of the country’s strongest beacons of public higher education.14

From 2008–2017, the state cut higher education spending by over 25 percent. Tuition rose by over a third. In the meantime, the university’s Board of Governors made it more difficult to lighten the tuition burden on low-income students. In late 2016, the board capped the amount of tuition revenue schools can redirect to need-based financial aid. The university’s scholarship office indicated that the new limit would markedly increase average student debt.15

Last year, for the first time, UNC-Chapel Hill instituted a purported $2,000 annual “fee” for business majors and $1,000 payment for business minors. The “unusual step,” according to the dean of the business school, reflected a purported “higher value” for the business degree. It was also claimed necessary because of an allegedly “modest” business school endowment compared to peers. “Private universities have been raising money for their endowments for hundreds of years, public universities now need to build comparable resources,” administrators explained.16

In 2016, the General Assembly and the UNC system launched an experimental NC Promise Tuition program, reducing tuition to $500 per semester at three universities—Elizabeth City State, Western Carolina, and UNC-Pembroke. Affordability may well be markedly improved at these three regional universities if the program is sustained by increased legislative appropriations. It is not unreasonable to worry, though, that as troubling measures like the $2,000 business major fee are applauded by legislators and administrators, the UNC system will consider its affordability obligations fully met by the NC Promise venture—even as Chapel Hill continues to move beyond the reach of middle-class Tar Heels.17

I don’t want to overstate the case. The undergraduate program at Carolina is still regularly cited by national publications as the best, or one of the best, bargains in American higher education. But UNC’s tuition moves over the last decade are not based in its traditional low-cost model. Nor can they be squared with a constitutional mandate to provide that the university’s benefits are “as far as practicable . . . free of expense.”18

The University’s departures from a focused concern for the felt needs of the marginalized and from historic commitments to academic freedom and integrity have proven more stark and relentless. In 2015, the Board of Governors closed the Law School’s Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity; and, in 2017, it demolished the operation of the UNC Center for Civil Rights, founded by Julius Chambers a decade earlier. The controversial moves, closing privately funded, faculty-driven initiatives, seemed to reject Graham’s call to represent “the voiceless.” I have written of them elsewhere, and I was director of the Poverty Center when it was shuttered, so I won’t rehearse my objections here. I’ll note, instead, characterizations of others.

Law School dean Jack Boger protested boldly that the decision to eliminate the Poverty Center was a direct and impermissible response to the center’s publications highlighting the challenges of economic hardship in North Carolina. Boger wrote:

In prior decades, UNC won the hearts and gratitude of the state’s people by combatting the scourges of peonage and child labor, of woefully inadequate medical care and appallingly bad public education. These earlier faculty-led initiatives drew fierce opposition from those who managed to benefit from others’ poverty and oppression. Yet the University pressed ahead, fulfilling what Graham celebrated as a tradition of our people: that, in Chapel Hill, they would find that “truth shining like a star bids us advance.”19

The Board’s decision to eliminate the central functions of the Civil Rights Center—by prohibiting it from litigation and advocacy—reflected, even more powerfully, an aversion to making “democracy effective in the unequal places.” American Association of University Professors (AAUP) president Rudy Fichtenbaum wrote, “Those who wish to curtain the center are more concerned with serving those with privilege than with protecting the rights of students and educating the public about issues of social and economic justice.” Ted Shaw, director of the center, was blunter: “Shame on these folks, they are on the wrong side of history in the struggle on behalf of black and brown poor people in the legacy of Julius Chambers.” As the Board debated and then voted to close the center, university system president Margaret Spellings raised not a whimper in protest.20

Placing the closings in broader perspective is illuminating. The UNC School of Law opened three academic outreach centers at my urging while I was dean (1999–2005): the Civil Rights Center, the Poverty Center, and the Center for Banking and Finance. All were donor-funded, dealt with matters crucial to the state, and tapped strong interdisciplinary capacities across the campus. The Banking Center sought to bolster expertise and scholarship related to the banking and financial services industries—encouraging student development and research in these fields and providing support for such commercial efforts nationwide.

While the Board spent months studying and eventually eliminating the two centers concentrating on the impoverished and racially marginalized, no study of the Banking Center was undertaken or even contemplated. In 2018, the North Carolina General Assembly appropriated $465,000 in recurring state funds to create a Law School Center for business entrepreneurism to provide “early stage” business ventures with legal counsel. The new program will, purportedly, aid new businesses and “fill the gap in North Carolina’s entrepreneurship ecosystem.” In 2016, the legislature created the North Carolina Policy Collaborative at UNC-Chapel Hill, providing an unrequested $4.5 million opening appropriation. The goal of the venture is to “provide research on environmental, water quality and economic issues in North Carolina.” North Carolina Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger and Chancellor Carol Folt reportedly came up with the plan because Berger was unhappy with the work of UNC’s internationally recognized environmental programs. He suggested that too many UNC faculty members were Democrats. Berger seems confident that the new venture will deliver research results more congenial to business interests. One of his staff members was hired to run it. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that professional service in aid of the economically powerful is seen by policymakers and university administrators as laudable while focus on the marginalized is forbidden.21

Nor were the center closings easy on academic freedom and free expression. After writing an array of articles critical of state poverty policies, I was warned by legislative leaders that I would be fired or the Poverty Center would be closed if I didn’t stop publishing pieces in the Raleigh News & Observer. When I refused, the legislators’ delegates on the Board of Governors made good on the promise, closing an academic program because its director had engaged in constitutionally protected speech. Senator Bob Rucho admitted as much, saying that it was necessary to shutter the program because I was advocating anti-poverty measures to which they were opposed. Chancellor Carol Folt and Provost James Dean knew explicitly of the cascade of threats—I testified about them openly at a hearing where they sat in the front row. Neither expressed a word of concern or objection. There are no more Bill Aycocks in Chapel Hill.22

In squelching the Civil Rights Center, the board explicitly interfered with faculty-developed instructional and research pedagogy for political purposes, in an unshielded intrusion on academic freedom. Politicians utterly unfamiliar with the goals and standards of legal education again decimated academic independence in favor of a preferred ideology. The center’s director, Ted Shaw, told the press, “I don’t think the ban is politically motivated, I know it was. Everybody knows it.” Steve Leonard, former UNC system faculty chair, said “[W]e have now reached a point where the Board is acting in ways that interfere with faculty prerogative on curriculum, research and service—if we don’t stand up now and at least try to maintain the authority we have over these things, we’re going to be in rough shape.”23

Nor has academic interference been limited to the Law School. In 2014, Omid Safi, a religion and politics scholar, left UNC to become director of Islamic Studies at Duke. He explained to the Daily Tar Heel that his departure was triggered by administrative censorship:

I study the intersection of religion and politics and no one at UNC had ever objected to anything I had to say about human rights violations in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel, or any other country. When I started to write about the North Carolina human rights violations, I was told in no uncertain terms that while people in the administration individually agreed, they were afraid that these kind of comments would lead the GOP to cut UNC’s budget. I found it easier to do political truth-telling at Duke than Carolina.24

History professor Jay Smith, who co-authored a 2015 book about UNC’s notorious athletic scandals, taught an undergraduate elective on big-time college athletics in 2016. It had been approved in the regular departmental order and turned out to be greatly popular with students. Unsurprisingly, it was rescheduled for the next year. But after unspecified “blowback”—from alumni, administrators, and the athletic director—the offering was unexpectedly cancelled. The chair said he’d been told the history department would suffer “adverse consequences” if he didn’t yield. So yield he did. Forty-five members of the history faculty wrote a letter of protest, citing “a serious infringement of freedom of inquiry.” The campus-wide faculty grievance committee reached the same conclusion. Chancellor Folt overturned the committee’s recommendation, finding “no undue” pressure from university administrators. “Undue” is an interesting term. Dr. Smith noted to The New York Times that “the university is operating like a crime family.”25

And then, of course, there is the longstanding athletic scandal about which Smith wrote and sought to teach. UNC-Chapel Hill apparently escaped sanction from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 2017 by claiming the organization had no jurisdiction over the widespread academic fraud—phantom or no-show classes heavily used by major sport athletes—at the center of the controversy. Campus leaders, unembarrassed, took stunningly contradictory stances before different regulators. Belle Wheelan, head of the academic accrediting agency, said Carolina’s shifting positions “didn’t pass the smell test.” NBA Hall of Famer David Robinson explained, in reviewing the results in 2018, that the position taken by Folt and UNC administrators “was the most disappointing thing [he had] ever seen in sports.” A few months earlier, the Condoleezza Rice Commission of the NCAA made implicit reference to Carolina when it concluded, “Member institutions [should] no longer be permitted to defend a fraud on the ground that all students, not just athletes, were permitted to benefit.” It is impossible to imagine such words being directed toward Frank Porter Graham or Bill Friday.26

Many faculty members see similar shortcomings in Chancellor Folt’s handling of the longstanding dispute over the maintenance and removal of UNC’s Confederate memorial, Silent Sam. Protests over the statue, which have stirred for decades, became acute and pervasive after the August 2017 deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Still, Folt refused to act, citing a 2015 state law that protects “objects of remembrance.” When the chancellor sought Governor Roy Cooper’s guidance, he advised that she had ready authority to remove it. But she demurred. After the statue was felled by activist protesters, Folt chastised the demonstrators forcefully. Impatient faculty and student critics demanded “leadership, not bureaucratic obfuscation.” The Board of Governors gave Folt and the Chapel Hill Trustees two months to develop a plan for the statue’s “disposition and preservation.” Folt emphasized her purported “consensus based” style of leadership and called for a collaborative process that would examine “goals, obstacles, principles, ideals and possible solutions for the problem,” noting that a poll revealed 70 percent of North Carolinians wanted the statue returned to its central placement on the campus. Judith Wegner, former chair of the UNC faculty, was unsparing in her response: “Folt’s gutless response to the Silent Sam controversy shames her predecessors as chancellors and the many faculty who have served UNC faithfully with their eyes on the greater good. Folt has been quite happy to go along to get along ever since she arrived here . . . the University of the People deserves better.”27

Over tremendous student, staff, and faculty opposition, Chancellor Folt and the Board of Trustees eventually recommended the construction of a $5.3 million building on campus to house the Confederate statue, requiring an additional $800,000 per year in security expenses. Protestors howled at the idea of “a shrine for Sam” and the Winston-Salem Journal added that Folt’s purported solution “sounded like a punch line to a bad joke.” No one seemed to disagree. The Board of Governors rejected the Folt proposal out of hand, almost without exploration. The Chancellor, oddly, seemed to find this result congenial as well.28

On January 14, 2019, Folt ordered that the statue’s base be immediately removed from the campus and announced that she would resign after graduation in May. A day later, an angered Board of Governors fired her. Hampton Dellinger, who had represented student protesters seeking the memorial’s removal, responded: “Along with UNC’s entire leadership structure (campus and system), Carol Folt was wrong about ‘Silent Sam’ when it mattered. Her leadership test came in 2017, post-Charlottesville. And she failed. Miserably.” Folt also demonstrated that trying to hang onto one’s job by refusing to do one’s job often fails on both fronts.29

The Long and Short

The University of Alabama’s Wayne Urban wrote just six years ago:

The University of North Carolina is a storied institution with a storied history. It serves as a kind of beacon for scholars in the rest of the South, a place that sets a standard to which other institutions in the region, especially their faculties, can aspire.

A “beacon” can be crucial, Urban noted, since “the life of the mind is in an unhealthy state throughout the South.” When a wide chasm exists, he explained, between the seeming consensus beliefs of a state’s political leadership and the core intellectual values of its faculty members, the intellectual climate for public universities becomes “stark.”31

It takes generations, or perhaps centuries, to build great institutions. But they can be wounded in a moment. That wounding occurs profoundly, now, at the University of North Carolina. The essential democratizing work of the nation’s first public university is diminished as a result. Its standing as a guidepost for other strong public schools has disappeared. A leading state flagship noted for open access, free inquiry, augmented opportunity for the disadvantaged, attentiveness to the demonstrable need of an ancient commonwealth, and the independence demanded by the blessings of liberty is increasingly abased. Chapel Hill is, increasingly, not Chapel Hill.

In July 2018, the university announced that it had passed the halfway mark in an astounding $4.25 billion capital campaign. During the tribulations of the Speaker Ban, Bill Aycock famously said, “North Carolina has come a long way, short on cash but long on freedom.” If we take “freedom” as Aycock’s shorthand for the values that most matter, it is accurate now to reverse Aycock’s phrasing—UNC is long on cash but short on freedom.31

This essay first appeared in the Spring 2019 Issue (Backward/Forward).

Gene Nichol is Boyd Tinsley Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law. He is the author of The Faces of Poverty in North Carolina: Stories from Our Invisible Citizens (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). He is also former dean of the law schools at UNC and the University of Colorado and past president of the College of William & Mary.NOTES

- Patty Courtright, “Brief Encounter Leads to 100 Years of Women at Carolina,” UNC News Services, October 10, 1997, https://www.unc.edu/news/archives/oct97/100.html (site discontinued). UNC’s move toward high percentages of female students began not long after the passing and implementation of Title IX initiatives in 1972 for equal access to education. In 1978, female students surpassed 50 percent for the first time in UNC’s history; see Sara Salinas, “The Road to a 60 Percent Female Campus,” Daily Tar Heel, April 12, 2016, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2016/04/the-road-to-a-60-percent-female-campus.

- McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949 (4th. Cir. 1951), cert. denied, 341 U.S. 951 (1951); counsel for the plaintiffs were Thurgood Marshall and Robert Carter, with Conrad Pearson of Durham, North Carolina, on the brief. See also Charles Daye, “African-American and Other Minority Students and Alumni,” North Carolina Law Review 73, no. 2 (1995): 675. L. J. Toler, “Carolina to Celebrate 50 Years of African-American Students,” UNC News Services, November 27, 2001, http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/nov01/bsm112601.htm (site discontinued).

- Warren Ashby, Frank Porter Graham: A Southern Liberal (Winston-Salem, NC: Blair Publishing, 1980), 94, 108, 136–139; James Leloudis, foreword to The State of the University, 2000–2008: Major Addresses by UNC Chancellor James Moeser, by James Moeser (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, distributed for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institute for the Arts and Humanities, 2018), 30; and Ashby, Frank Porter Graham, 94, 108, 136–139.

- William D. Snider, Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 7, 10, 11, 23; William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 47–48.

- NC Const., art. IX, § 9, https://www.ncleg.gov/EnactedLegislation/Constitution/NCConstitution.html; Snider, Light on the Hill, 2; and Ashby, Frank Porter Graham, 94, 108, 136–139.

- Ashby, Frank Porter Graham, 158–161; Moeser, The State of the University, 40; and Snider, Light on the Hill, 270–280, 329.

- Ashby, Frank Porter Graham, 90–94; Snider, Light on the Hill, 179–180, 188; Generation of Change: William Friday, Terry Sanford, and North Carolina’s “Greatest Generation” 1920s–1972, directed by Steve Channing, aired January 8, 2015, on UNC-TV; and William C. Friday, in discussion with the author, October 2004.

- Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries, 465; Snider, Light on the Hill, 189–199, 203–205.

- Rob Christensen, “Nichol is Only the Latest Academic Freedom Case,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), February 21, 2015, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/politics-columns-blogs/rob-christensen/article11302841.html.

- Ashby, Frank Porter Graham, 127, 140; Snider, Light on the Hill, 190–192.

- Gene Nichol, “Bill Aycock and the North Carolina Speaker Ban Law,” North Carolina Law Review 79, no. 6 (September 2001): 1725, 1728–1729. See also “William B. Aycock,” UNC General Alumni Association, accessed December 10, 2018, http://alumni.unc.edu/william-b-aycock-1957-1964. Nichol, “Bill Aycock,” 1725, 1736–1737.

- See Mickey Blackwell, “Aycock Looses Searing Blast at Speaker Gag Law,” Daily Tar Heel, November 10, 1963. Nichol, “Bill Aycock,” 1733–1736, 1735.

- Moeser, The State of the University, 22–24, 23.

- Snider, Light on The Hill, 255.

- Zoë Carpenter, “How a Right-Wing Political Machine is Dismantling Higher Education in North Carolina,” The Nation, June 8, 2015, https://www.thenation.com/article/how-right-wing-political-machine-dismantling-higher-education-north-carolina/. See also Blake Weaver, “BOG Approves Business School Tuition Increases, Other School Fees,” Daily Tar Heel, March 27, 2018, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2018/03/unc-system-fees-bog-print-0327.

- Jane Stancill, “Extra Fee Proposed for UNC Business Majors as ‘a Very Last Resort,’” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), January 25, 2018, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article196725009.html. See also Hannah Lang, “Incoming Kenan-Flagler Students To Experience Tuition Increase,” April 10, 2018, Daily Tar Heel, http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2018/04/bschool-0411 (quoting Anna Millar, co-director of undergraduate business school program).

- Bryan Anderson, “NC Residents Are Within 150 Miles of $500 Tuition,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), accessed December 10, 2018, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article88692132.html.

- “Best Values in Colleges,” Kiplinger Report, December 2017, http://www.kiplinger.com/tool/college/T014-S001-find-best-colleges-value-rankings/end_page.php?school=9313.

- John Charles Boger, “A Statement from Dean Boger: UNC Centers and University Values,” University of North Carolina School of Law, February 18, 2015, http://www.law.unc.edu/news/2015/02/18/a-statement-from-dean-boger-unc-centers-/; Scott Jaschik, “Who Is Being Political?,” Inside Higher Ed, February 19, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/02/19/unc-board-panel-wants-shut-down-center-poverty-led-faculty-member-who-criticizes.

- Stancill, “Supporters Rallying Behind UNC’s Civil Rights Center,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), May 10, 2017, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article149682089.html#storylink=cpy; Stancill, “UNC Board Bans Legal Action at Civil Rights Center,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), September 8, 2017, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article171979707.html.

- “UNC School of Law Receives a $1.53 Million Gift for New Entrepreneurship Program,” University of North Carolina School of Law, June 18, 2018, http://www.law.unc.edu/news/2018/06/18/153-million-gift-for-entrepreneurship-program; Stancill, “Legislature’s Push For Environmental Policy Causes Unease at UNC,” Charlotte Observer, August 20, 2016, www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/education/article96951662.html; Rick Seltzer, “When Lawmakers Set Up a Policy Research Center,” Inside Higher Ed, August 15, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/08/15/legislature-mandated-environmental-policy-center-ruffles-feathers-unc; and Lisa Sorg, “Monday Surprise: Jeffrey Warren Named Research Director of NC Policy Collaboratory,” Progressive Pulse, NC Policy Watch, March 6, 2017, http://pulse.ncpolicywatch.org/2017/03/06/monday-surprise-jeffrey-warren-named-research-director-nc-policy-collaboratory/.

- See, generally, Nichol, “Lessons on Political Speech, Academic Freedom, and University Governance from the New North Carolina,” First Amendment Law Review 16 (2018): 39; Ned Barnett, “The World According to Rucho,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), February 28, 2015, https://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/ned-barnett/article11628902.html.

- Nichol, “Lessons on Political Speech,” 63, 64.

- Ibid., 57. See also Leah Moore, “Former UNC Faculty, Staff Explain Reasoning For Taking Offers at Duke,” Daily Tar Heel, March 9, 2017, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2017/03/unc-has-a-net-faculty-gain-despite-offers-faculty-cannot-refuse.

- Stancill, “A UNC Course That Dealt With Athletics Scandal Is Canceled. Now Some Want To Know Why,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), June 2, 2017, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article154031604.html; Michael Powell, “North Carolina’s Dominance Fails to Cover Cheating’s Stain,” New York Times, March 31, 2017, https://nytimes.com/2017/03/31/sports/ncaabasketball/north-carolina-final-four-cheating-fake-classes.html.

- Andrew Carter, “No Significant Penalties for UNC in NCAA’s Long-Awaited Report on Academic Scandals,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), October 13, 2017; Dan Barkin, “UNC’s Statements to the NCAA Didn’t ‘Pass the Smell Test,’ Accreditor Said,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), November 22, 2017, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/unc-scandal/article186019288.html; Dan Kane, “UNC Defended Classes to the NCAA. Now the Accreditor Has Questions,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), November 9, 2017, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/unc-scandal/article183717756.html; and Brian Murphy, “Former NBA Star Calls UNC Case ‘Most Disappointing Thing’ He’s Seen in Sports,” News & Observer, May 10, 2018, https://www.newsobserver.com/sports/article210739484.html.

- Vimal Patel, “UNC’s Chancellor Is a Consensus Builder. Silent Sam Is Her Greatest Test,” Chronicle of Higher Education, September 25, 2018, https://www.chronicle.com/article/UNC-s-Chancellor-Is-a/244629; Jordyn Williams, “Folt Claims 70 Percent of N.C. Residents Want Silent Sam Back in McCorkle Place,” Daily Tar Heel, September 24, 2018, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2018/09/faculty-executive-committee-0924-silent-sam-unc; Patel, “unc‘s Chancellor Is a Consensus Builder”; and Judith Wegner, “Chancellor Folt Needs to Display Better Leadership,” Daily Tar Heel, September 7, 2018, 3.

- “Our View: A Bad Solution for Silent Sam,” Winston-Salem Journal, December 8, 2018, https://www.journalnow.com/opinion/editorials/our-view-a-bad-solution-for-silent-sam/article_67537f2c-732e-5f8d-b752-1875a11a7933.html; Stancill, “Protesters March, Call for Strike of UNC Professors and Teaching Assistants,” December 3, 2018, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/article222586130.html; “Our View,” Winston-Salem Journal; and Stancill and Tammy Grubb, “‘Back to the Drawing Board’—UNC Board Rejects Latest Silent Sam Plan. New Panel Launched,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), December 14, 2018, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article223096755.html.

- Stancill, Grubb, and Julia Wall, “Silent Sam Pedestal Removed After Order From UNC Chancellor Carol Folt, Who Is Stepping Down,” January 14, 2019, News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), January 14, 2019, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/article224526250.html; Stancill and Carli Brosseau, “UNC Board Tells Chancellor Folt to Leave Her Job in 2 Weeks—Earlier Than Expected,” January 15, 2019, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/article224561590.html.

- Wayne Urban, review of The New Southern University: Academic Freedom and Liberalism at UNC, by Charles J. Holden, H-NC, May 2013, https://networks.h-net.org/node/8909/reviews/14175/urban-holden-new-southern-university-academic-freedom-and-liberalism.

- William Brantley Aycock, Speeches and Statements of William Brantley Aycock (1957–1964) (Chapel Hill, NC: Colonial Press, 1989), 191, quoted in Nichol, “Bill Aycock,” 1736.