“We would play tennis even after they turned off the lights on the courts,” my father told me, as he reflected on his days in the Panama Canal Zone (PCZ).

Tennis became their sport; my father, his sister, and his brother perfected their craft and became so good that they and other neighborhood youth all received athletic scholarships to study and compete at HBCUs throughout the South. But more so, those lessons-turned-victories from the tennis courts of Rainbow City allowed my father “to become somebody.” Motivated by his parents and family members like his Uncle Georgie, who “used to cut grass in the Zone and told us that they did those hard jobs so that we did not have to,” my father took his tennis skills from the Canal Zone to Huston-Tillotson College (now University) in Austin, Texas.

The desire, and the need, for Black athletes in Panama to use their athletic talents to rise above their circumstances has remained constant over the years. But the transnational sporting networks sustained by Black physical educators and coaches that allowed my father and many other Black Panamanians to use their athletic talents at HBCUs across the “Continental South” have faded into nonexistence. The decades that separated my father’s departure from Rainbow City in 1974 and my arrival to Arco Iris in 2012 prevented me from seeing the change in these networks until my father shared memories of his journey through tennis to what his generation called “the States.” The decades between the 1970s and the 2010s—between his departure from the former US Panama Canal Zone and today’s Republic of Panama—were filled with changes that freed Panama of US occupation on Panamanian soil, including the former Canal Zone. The last act of reversion would be on the last day of the twentieth century as the twenty-first century commenced in 2000.

To make sense of the changes and translations, I had to take a trip into my father’s memory and trace the places and people from his former home. To do so, I needed to jump back a few generations and remap what we understand of the US South to include the former US Panama Canal Zone. The fact that this US neocolony no longer exists does not erase the people who lived there nor the lives they made within its border. I wondered, What is the South? What makes a place southern? Is it within a specific continental geography only? Is it an aesthetic? Or an accent? Or is it the Jim Crow policies enacted by the US government to keep Black people subordinated and disenfranchised? In the latter case, the US Panama Canal Zone is as southern as Texas, a “slice of Dixie, exported some 2,000 miles from Mississippi, where the song of race hate is the same, but the words are different.” Or at least it was. Connecting the Panama Canal Zone to the US South through laws and policies forces us to consider how Black Panamanians, the people most impacted by segregation, experienced and navigated it. If Black Americans turned segregation into congregation—in which “congregation” is the “network of athletes, administrators, coaches, sportswriters and fans who sustained [the sport]”—so did Black Panamanians, and they often did it together. This is a very southern story.1

“Loney Ball, Loney Ball,” my father said, half laughing, while giving his best impersonation of the day Mr. Stanley Loney forced them to learn tennis in the gym of Escuela Secundaria de Rainbow City (Rainbow City High School), one of the US-operated segregated schools that served the “local-rate community” in the PCZ. By the time my father received this impromptu tennis lesson, “local rate” was a stand-in for “non-US Black,” replacing the earlier language of “Colored” and “Silver” that had dominated the Zone’s geography and enforced its racial hierarchies. The term originated from the differences in pay in the Canal Zone (American rate and local rate).

“I am tired of y’all saying ‘Loney ball,’” he motioned, mimicking the elderly physical education teacher’s frustration that the youth only wanted to play basketball.

“You know where the gym is?” he asked me midway through his story, forcing me to recollect the months I spent living in his childhood home at 5918A Andrews Street in the formerly segregated Rainbow City. I knew the gym, but when I walked the streets in 2012, the days when the US government controlled every aspect of life within the Canal Zone were long gone. It was hard for me to see what he saw because my father remembered Rainbow City, a local-rate community on the Atlantic side of the US Panama Canal that had ceased to exist by the time I was born. My memories were of Arco Iris, the Spanish translation of “rainbow” that became the settlement’s official name after the town reverted to the Panamanian government in 1979.

He tried to give me the best directions that his memory could serve. “Do you know where the ice house is?” I did, and I didn’t. I only knew the building as Complejo Penitenciario Nueva Esperanza, which was once the Canal Zone cold storage warehouse and morgue. He continued painting the picture of it when he worked there, assigning plot numbers for the dead waiting to be buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery. The building is still there, next to Cemeterio de Monte Esperanza, the name it now bears in this English-to-Spanish translated environment. However, my memory only called up the crumbling prison mostly filled with the Black men I remembered sitting on the window’s ledge.

That was the only image I could conjure as I recalled my days journeying through the former Black Canal Zone town to get to the private school in Margarita where I taught elementary math at an elite private school. I came to teach there in the 2010s for the same reason my grandmother worked as a domestic there starting in the 1950s—our employers valued our English-speaking skills for their children’s benefit. Margarita—another formerly segregated town on the Panama Canal Zone’s Atlantic side—was initially constructed for whites and, later, “Americans.” In Margarita, as with all of the US settlements within the PCZ, race and ideas about race determined spatial development. The town was designed to be far enough away from Rainbow City but conveniently close enough for Black domestic workers like my grandmother to maintain white American families’ homes.2

I recalled the Centro Regional Universitario de Colón and the number of discolored buildings that once served as the segregated school buildings for Black children, including the gym my father was describing. I wish I could see the basketball court that Mr. Loney transformed into a tennis court with American school chairs fashioned into a makeshift net over the half-court line.

Although the US Panama Canal Zone does not exist anymore, the sense of place and transnational networks Black people created from within segregated enclaves are still inscribed within the former Zone’s terrain and in the memories of those who lived, worked, played, and died there. The physical landscape has changed, making it difficult to see, but the stories of the former Canal Zone can help us map out the extensive reach of the Black diasporic world. My father couldn’t recall if Mr. Loney had ever lived in “the States,” but I am positive that he was connected to the country of his employment through the reach of the Black press.3

When he became my father’s tennis instructor, Mr. Loney was employed by the US Panama Canal Zone and paid according to their two-tier pay scale based on nationality, in which race was also ascribed. (He was on the Silver Roll until that language was replaced with “local-rate.”) In addition to his duties as physical education teacher, Mr. Loney supervised the gym and presided over open gym in the afternoon and evening hours. “He used to sit in the corner of the gym on his typewriter and type all of our results from the matches,” my father said. Well after school hours, once he finished coaching/teaching or typing, he would wait on the bus to carry their stories beyond their borders, literally. On his way home, departing the United States territory and crossing the border back into La Republica de Panamá, he dropped off their results to the English and Spanish newspapers in Colón City.

As my father recounted and moved his fingers, emulating Mr. Loney’s strokes on his typewriter, I was struck by how far Mr. Loney’s words reached. Those words—turned into printed stories in newspapers throughout the isthmus, which he cut out and sent to coaches in the United States— would connect my father, his siblings, and many Black youths from the Canal Zone and the Republic to the “sporting congregations” that Black Americans created in the “Continental South.”

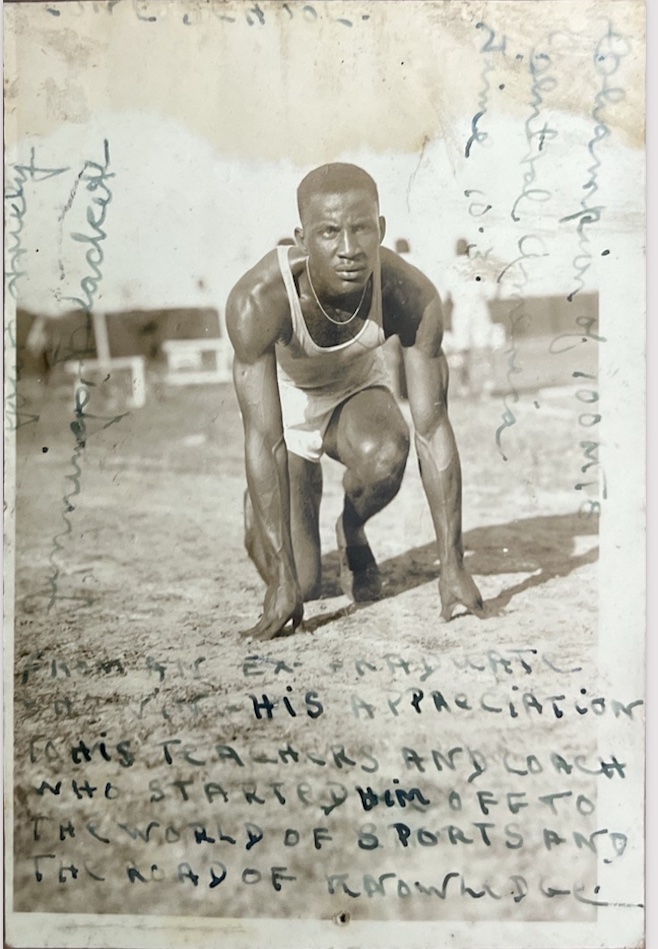

Unbeknownst to my father, Mr. Loney was also a seasoned journalist. As I perused the archives of The Panama Tribune, a Black Panamanian newspaper, looking for stories of Black Panamanian athletes, Stanley Loney’s name kept appearing. Beyond sports articles that carried his own triumphs as a track athlete, Mr. Loney covered the Colón beat, reporting on murders, disputes, and other news pertinent to Panama’s Black West Indian communities. He understood well the power and reach of his words.

Stanley Loney was among the first generation of Panamanians of West Indian origin to remap the Panamanian isthmus, including their multiple histories and tying them to the Global Black South. Loney was a track star, and he ran. He, like many others within their enclaves in the PCZ and Panama, competed for a nation that wrote a new constitution to exclude him from citizenship and wanted only the benefits from his athletic training and his parents’ labor—for Panama, the Canal, not for them. And they still excelled. Fittingly, they used the same things that prohibited their Panamanian citizenship—Blackness, migrancy, and language—to forge diasporic connections. The precarity of Panamanian citizenship, in combination with their parents’ colonial Caribbean backgrounds and the US-operated segregated PCZ school system, provided them with multiple avenues to congregate across national boundaries and language differences at international sporting competitions. These would be some of the earliest pipelines forged to HBCUs.

Mr. Loney’s parents were from Jamaica, British West Indies, like my great-grandfather, Henry Norman McEachron, better known as “Mr. Mac.” Thousands of migrants, primarily from the British and French Caribbean colonies, made their way to the Central American Isthmus during the construction of the US Panama Canal. These were “true” West Indians, born in the Caribbean islands, who went to “try their luck” on the big ditch. When they literally dug and dynamited their way to “A Land Divided, A World United,” as became the Panama Canal’s motto, they created new geographies. New maps, with a new canal, erasing and replacing Afrocolonial settlements with AfroAntillean work towns.4

The Black migrants came from far and wide, including Black folks from the United States, both young and old. Some were like my Barbadian-born great-grandmother, Rosalie Braithwaite Clark, who was brought to Panama as a child in an adopted family hoping to achieve a better life than the ones they left. Hundreds of thousands came. Hundreds of thousands came, many subjected to Jim Crow segregationist laws and policies as the “US officials set out to make the Canal Zone an extension of the United States, culturally and racially.” The government implemented a system called Gold and Silver Roll. Gold designated white and American, and Silver nonwhite and non-American. Most “Silver” employees were Black people from the British-and French-controlled Caribbean colonies and their Panamanian-born descendants. Thousands died. Thousands continued their journeys elsewhere to the banana plantations of Bocas del Toro, or to Costa Rica, the sugar mills of Cuba, and maybe even Harlem. Thousands also remained in Panama. Their children would embark on a long journey to become Panamanian citizens and create community through mobilization against racist policies, producing their own newspaper, baking pan bon (Easter bun), or forming sport teams, whether in the PCZ or elsewhere.5

My father believed that Mr. Loney’s transfiguration of the basketball court was simply his annoyance with their basketball obsession, but Mr. Loney transformed their worlds from within the segregated gymnasium, affording them new possibilities and connecting them to a Black diaspora. The opportunity he gave them through tennis was very different from what the segregated enclaves were expected to produce, namely, future employees. Rather than feed this provincial pipeline, Mr. Loney reached to greater prospects for his students, translating Rainbow City’s status as a US neocolony into easier access to HBCUs. When he taught them how to return the fuzzy yellow ball over the row of chairs, he allowed them to decide their futures.

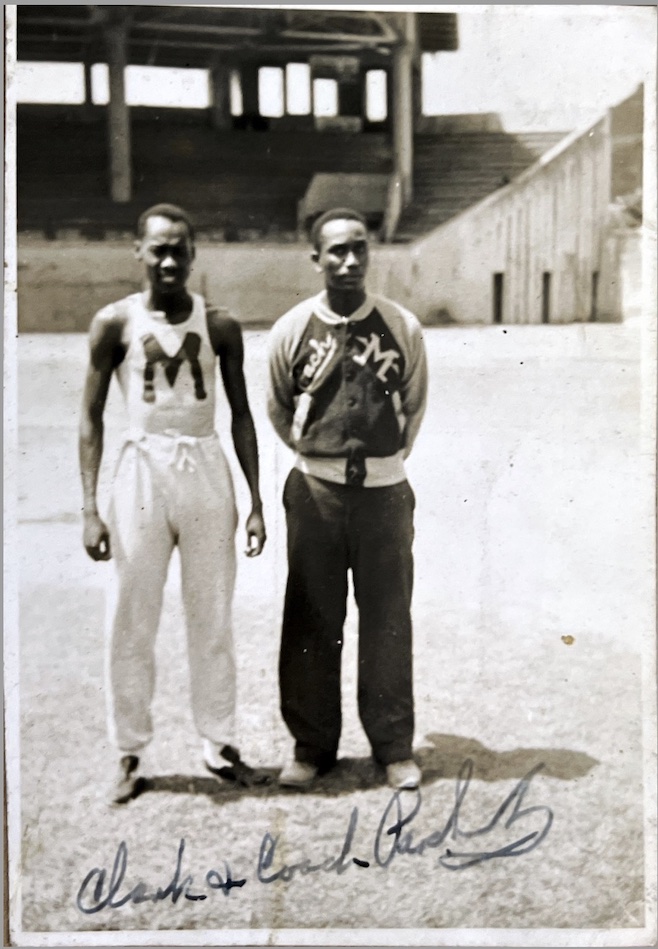

This moment had been decades in the making. Since the 1930s, Mr. Loney had been part of an intricate network of athletes, coaches, and physical educators who used their connections within both the racially segregated Panama Canal Zone and a hostile Panamanian republic to send talented Black athletes primarily to HBCUs in the US South. Many of these routes and pipelines come to life within the pages of Black newspapers, which traced places, results, and cultural context in their write-ups. The Chicago Defender reported on the “Sepia boys that can run as fast as ducks from Panama” at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA), the Catholic HBCU in New Orleans. (Their coach was the famed Black Olympian Ralph Metcalfe.) An alumni update from La Boca School celebrated that “Jennings Blackett, champion sprinter at the last Central American Olympics, is now pursuing a course of dentistry at Xavier University at New Orleans.” And The Panama Tribune, in announcing Clayton Clarke’s departure to Xavier University, noted the strength of the pipeline: “It is significant that nine years later one these students today is able to help other local athletes obtain higher education and at the same time improve his athletic skills in the United States.”6

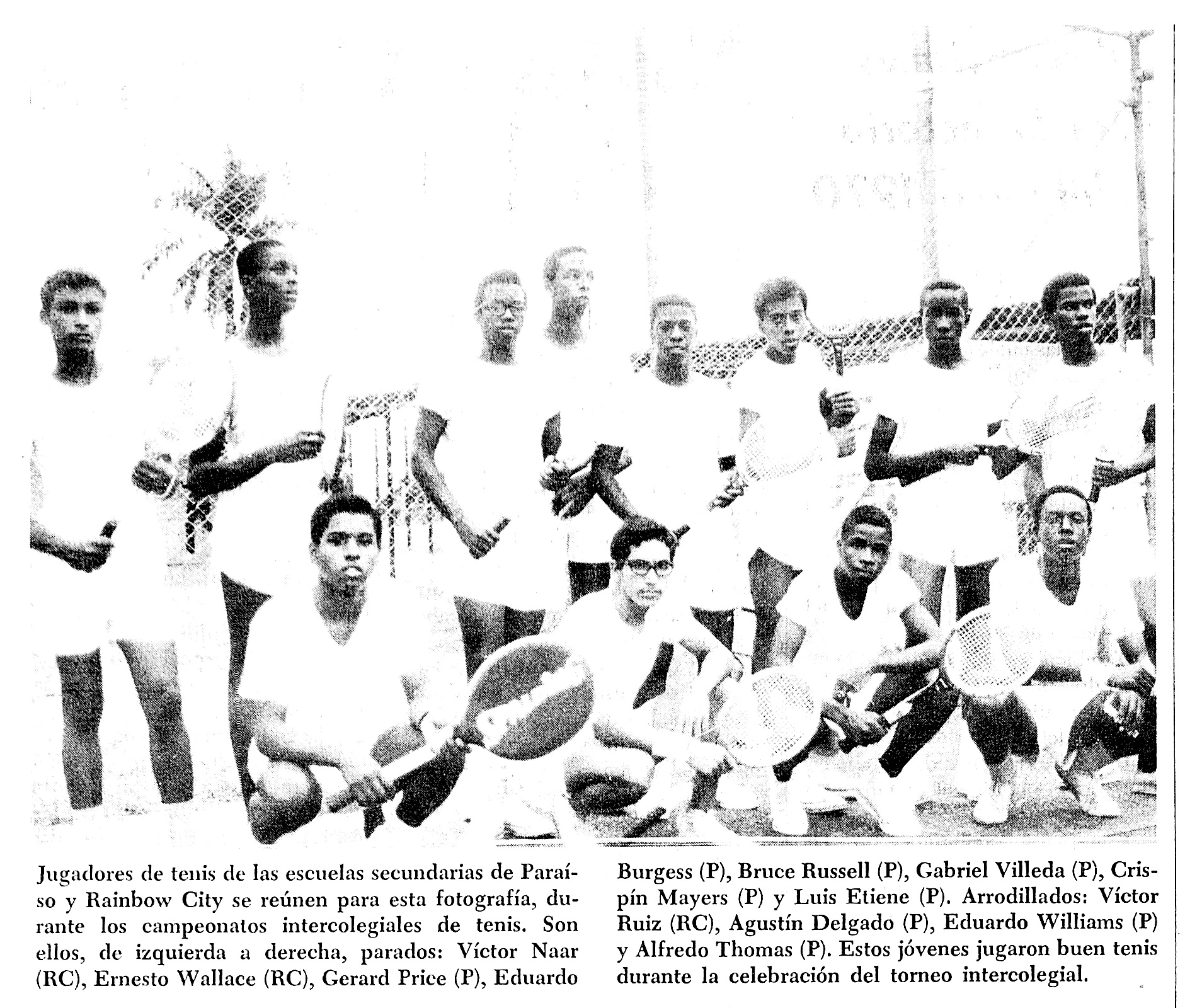

The road to New Orleans and other southern institutions of higher learning for Black Panamanian youth, specifically Black youth of West Indian origin, was paved by coaches and physical educators, among them Aston Marley Parchment, who bridged the Atlantic World as athlete, educator, and advocate. For many years, Loney and Parchment were colleagues within the Canal Zone’s segregated physical education and recreation departments. Parchment, like Loney, was deeply intertwined within the Global Black South. He was born in Jamaica in 1910 and, by 1913, was living and receiving his primary education in the US Panama Canal Zone. In 1929, after attending high school in Jamaica, Coach Parchment returned to Panama and began working at the segregated schools of the US Panama Canal Zone. He taught physical education and coached sports at La Boca School, La Boca Normal Training School, and Paraiso High School, and also served as the first president of the Canal Zone Colored Teachers Association. After sending several Black track student-athletes to XULA over the years, he attended the university himself, receiving a Bachelor of Science in physical education in 1959. He would also later work in the athletic and intramural departments at Xavier in the 1970s.7

In addition to his role within the Canal Zone school system, Coach Parchment formed Club Mercurio and trained some of the country’s top athletes. After “local-rate” youth swept the track and field competitions at the 1951 Bolivarian Games in Venezuela, the Panama American wrote, “Aston Parchment, La Boca physical director . . . has produced more Central American Olympic material than any other Isthmian track coach.” The star of the article was a fourteen-year-old Panamanian of West Indian descent, Charlotte Gooden, exclusively trained by Coach Parchment. From the segregated playgrounds of the Canal Zone to Panama, where her citizenship was in question, Gooden ascended to become a member of the famous Tuskegee Tigerettes track and field team. That program also produced Alice Coachman, the first Black woman to win an Olympic Gold Medal.8

Many other Black Panamanian women would run their way into history through the coaching they received at HBCUs. Lorraine Dunn, Jean Holmes, and Marcella Daniel, all graduates of Paraiso High School, went on to compete on Tennessee State University’s storied Tigerbelles Women’s Track and Field Team, coached by legendary coach Ed Temple. In 1960 and 1964, they and Gooden became the country’s first women athletes to compete in a Summer Olympics. Many of the nation’s athletic “firsts” were Panamanians of West Indian descent trained on HBCU fields of competition.

“Mrs. Phillips was so mean,” my father exclaimed after seeing her picture in his senior yearbook. Following her successful track and field career, Charlotte Gooden returned to the Panama Canal Zone. She married and became Mrs. Phillips, a physical education teacher at the Escuela Secundaria de Rainbow City. I laughed a bit, but I was amazed. They had an Olympian as a physical education teacher, and he was unaware.

But I still wanted to know exactly how my dad made it to Huston-Tillotson College (HT), when, indeed, there were other schools he could have attended. “I don’t know how Mr. Loney got in contact with HT,” he said while searching his memory to return to those days. “I remember waiting by the phone with my mother for Coach Wilson to call us.” At that time, Coach James Wilson was the athletic director at HT. After a pause, he started up again. “You have to remember Mr. Petit was at HT, and he’s from Paraiso,” he continued, as he began to piece it together. “And Mr. Loney used to teach in Paraiso before coming to Rainbow City.”

My father’s memory served him well. In 1953, Mr Loney was hired as the physical education instructor for Red Tank and Paraiso elementary schools. He remained on the Pacific side until he was transferred back to Rainbow City in 1963. It’s likely he crossed paths with Mr. Petit, but if he didn’t, he definitely knew of the “ranking Negro tennis star,” as a 1949 Chicago Tribune article called him.9

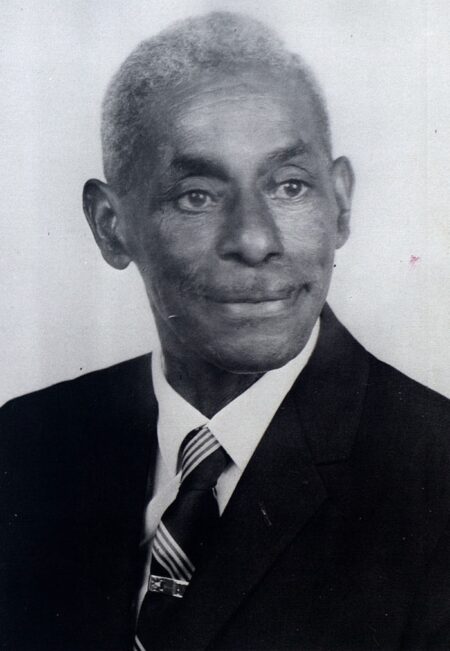

I’ve always known of Mr. Petit, but I never met him. He transitioned from this earthly plane in 1986, about one year before I was born. But, over the years, both my parents spoke highly about him. Archile “Chile” Eugenio Petit was born in 1920 in Red Tank, a segregated Silver (Black) town on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal Zone. His parents were French-speaking immigrants from Martinique and Guadeloupe. He was a standout athlete in multiple sports and won several national tennis titles. Mr. Petit was like Stanley Loney, Aston Parchment, Jennings Blackett, Charlotte Gooden Phillips, and many Black Panamanian athletes of West Indian descent who were reared in the Panama Canal Zone before and during the changes that Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the Remon–Eisenhower Treaty (1955) brought to life there. Especially for Black residents.

The new treaty led to many changes, including transformations in the Canal Zone school system. White schools converted into schools for US citizens, and Colored Schools converted into Latin American Schools for Panamanians aligned with the Panamanian school system. Spanish became the principal language of instruction instead of English. These emerging treaties and the politics leading up to them also ushered in the removal of hundreds of Black families and the closing of their Silver communities in the Canal Zone, including Petit’s hometown of Red Tank, as the US government either rehoused some in the PCZ or effectively deported them into the Panamanian republic. As their lives, networks, and personal geographies were disrupted, many with resources decided to leave the isthmus altogether for the United States.10

I don’t know why Petit chose to leave in 1956. Still, I know that Petit did not decide in isolation from the changing racial geographies that attempted to control his life. That was the name of the game for Black people in the PCZ. Regardless of their ambition, preparation, or intellect, racial hierarchies in the US neocolony predestined West Indian residents to staffing the railroad, dock facilities, and low-level clerical and administrative positions. I can only infer from my father’s stories about Petit’s ambition and athletic talent that he wanted to be more than an office clerk in the PCZ—especially after seeing his Olympic teammate, George Stewart, known as the “King of the Top Spin,” trade in his PCZ clerical position for a tennis scholarship at South Carolina State College for Negroes.11

Somehow and someway, the ambitious thirty-six-year-old Petit made it to Huston-Tillotson on a tennis scholarship. Perhaps Petit connected with the college through the younger Randolph T. Barber from neighboring Paraiso, who was already on HT’s tennis team, or perhaps it was one of the other Black Panamanians there as student-athletes. A 1955 article published in the Austin American-Statesman listed four student-athletes from the Panama Canal Zone excelling on HT’s courts and track in that era: David Bonnick, Teodoro Martinez, Clifford McPherson, and Carlos Hyacinth.12

Sport, and tennis and its connection to diasporic Black sporting geographies specifically, became the catalyst for change in Petit’s life, helping him to navigate the racial hurdles in his life. By 1957, the American Tennis Association, the oldest Black noncollegiate sporting organization in the United States, ranked Petit as the eighteenth best player in the country. That year, he participated in the national tournament and lost in the championship match of the Intercollegiate Men’s Final to William “Bill” Monroe of Hampton Institute. That was quite the accomplishment for someone who had entered the country one year earlier and was thirty-six years old. He was good.

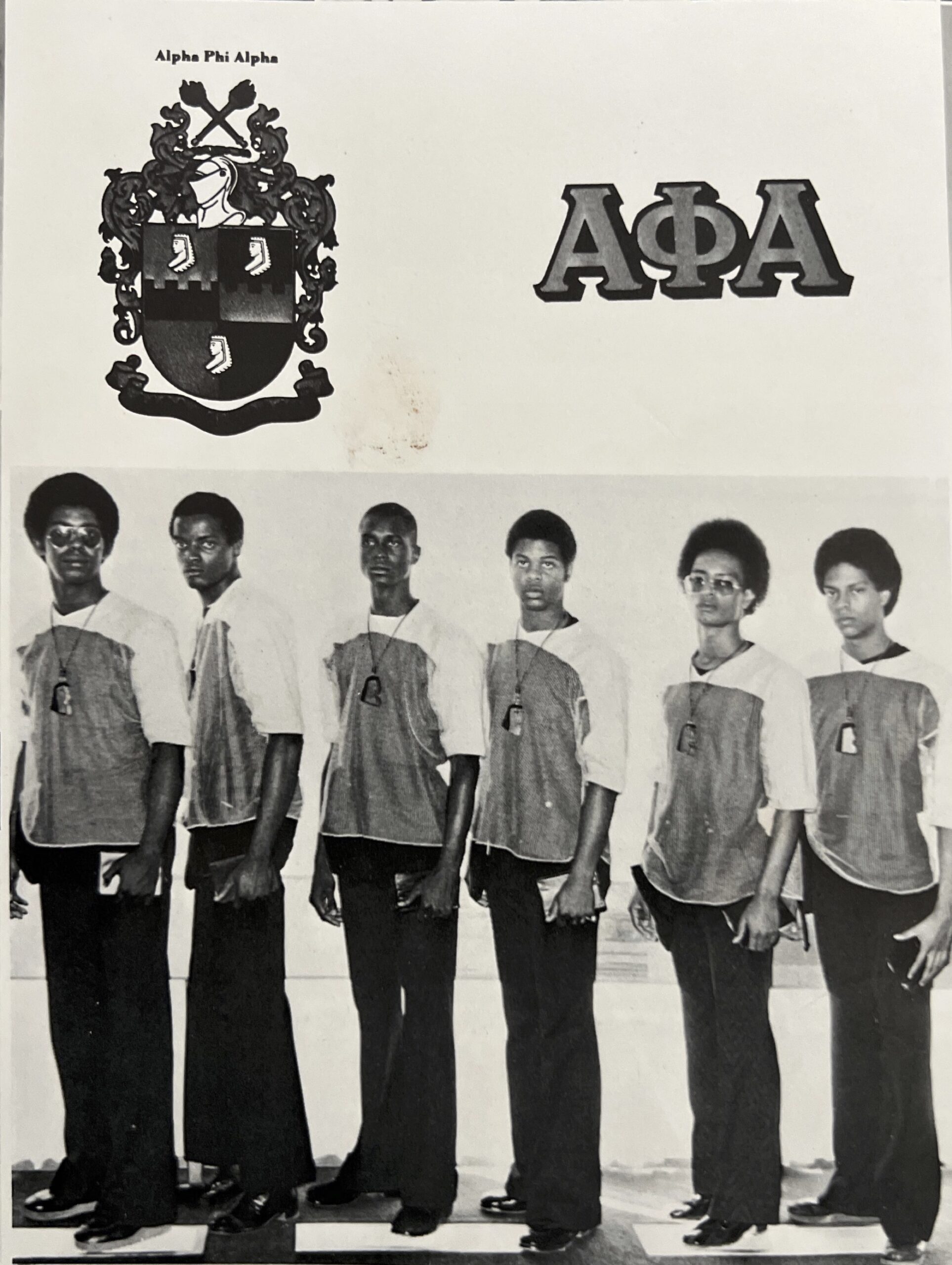

While a student at HT, Petit joined Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. By the time he became president of the local chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha in 1974, his work as a connector of Black Panamanian athletes was well-known. One article announcing his ascension to the role noted that he had, over the previous fourteen years, “been sending Panamanian tennis players and other athletes to numerous colleges and universities,” including “four Panamanians on the HT varsity tennis team; five at Prairie View; two at Texas Southern U; two at Hampton Institute; and one at Central State U in Ohio.”13

My father arrived at HT in 1974, part of Petit’s pipeline, and by the next school year, he would also join Alpha Phi Alpha. But things were changing in the pipeline that connected young Black Panamanians to HBCU athletic programs. The race-based dual education system they so much depended on in both the United States and the US Panama Canal Zone was fading. The forceful push and realities of integration were happening, and Black institutions were taking the hardest hits. During the consolidation of the dual-education system, US parents objected to having their children taught by non-US-citizen teachers from the Zone’s Latin American Schools, mostly Black Panamanians. The Latin American schools on the Canal Zone would meet their demise by the end of the 1977 school year. As the PCZ consolidated its schools, the pillars and connectors, in the form of Black coaches and physical educators like Loney, were reaching retirement age and being “phased out.”14

Upon my father’s graduation from HT in 1978, it was difficult for him to reach back to the same intuitions that paved his opportunity. They were closed, and most of his teachers’ and coaches’ roles were no longer needed in PCZ’s new single education system. Black schools across the US South met the same fate as the ones on the PCZ that split the Central American isthmus nearly a century before. As my father followed in Petit’s footsteps to become a physical education teacher, he witnessed Black students in Austin bused across the city to integrate schools. The same was happening in the PCZ. There was no more walking to Escuela Secundaria Rainbow City and hustling to the neighborhood tennis courts once the final bell rang. Rainbow City youth were now mounting big yellow American school buses, journeying to Cristobal High School miles away from their homes, or opting for schools in the republic paid for by the US government. Those buses were taking them miles away from the Black-led schoolhouses where their coaches could convert a basketball gym into a tennis court with chairs and transform lives. A makeshift tennis court that could ultimately connect them to HBCUs where their athletic talents could help them “become somebody.”

I’ve try repeatedly to re-create the images, boundaries, and institutions like the corral, clubhouse, and tennis courts that my father wants me to walk with him in his memory. Some days I feel like I can see what he sees. But it isn’t easy. I see what remains: the attempts to erase further our stories from the country’s memorial geography of Blackness. It’s displaced. It’s in ruins. It’s now a jail with Black bodies. It’s now translated into Spanish. The translations have shaped new racial geographies along the isthmus because they aren’t simple conversions from one language to another. They were part of a plan of singular Panamanian nationalism to tell the country’s story in a Hispanicized way. It is urbicide, a “violence against the city” and against the sense of place these mostly English-speaking Black people created in their segregated communities in the Canal Zone and throughout the isthmus. Ser panameño or to be Panamanian also means “to speak Spanish.” This English-to-Spanish translation is part of a continuing destabilizing process for Black Panamanian communities, intentionally disconnecting us from our histories, our social and physical landscapes, and from Black diasporic traditions and institutions like HBCU athletics.15

This essay is from the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 2: Summer 2023).

Javier L. Wallace is a postdoc at Duke University. He completed his PhD at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on Black athletes from the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Additionally, he is the founder of Black Austin Tours and the cofounder of AfroLatinx Travel and BlackPackas.

Header image: Physical Directors of PCZ, ca. 1940s, including Coach Stanley Loney (seated third from right) and Coach Aston Parchment (standing third from left). Courtesy of the Aston M. Parchment Scrapbook, Museo Afrocaribeño de Panama, Ministerio de Cultura (Panamá).NOTES

- “Gold & Silver: Panama Canal Zone has strange Jim Crow setup,” Ebony Magazine, May 1948, 8; on “sporting congregations,” see Derrick E. White, Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Jake Gaither, Florida A&M, and the History of Black College Football (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

- Maya Doig-Acuña, “The Most Caribbean of Stories,” Southern Cultures 26, no. 4 (2020): 12–23.

- Katherine McKittrick, “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place,” Social & Cultural Geography 12, no. 8 (2011): 947–963.

- Kaysha Corinealdi, “Envisioning Multiple Citizenships: West Indian Panamanians and Creating Community in the Canal Zone Neocolony,” The Global South 6, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 87–106; Jarvis McInnis, “A Corporate Plantation Reading Public: Labor, Literacy, and Diaspora in the Global Black South,” American Literature 91, no. 3 (2019): 523–555; Velma Newton, The Silver Men: West Indian Labour Migration to Panama, 1850–1914 (Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 1984).

- Kaysha Corinealdi, Panama in Black: Afro-Caribbean World Making in the Twentieth Century (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 14.

- Frank Albert “Fay” Young, “The STUFF IS HERE: Past—Present—Future,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), July 16, 1938, 9; La Boca School, The La Bocan 1940(Panama City, Panama: 1940), 19, Digital Library of the Caribbean, https://dloc.com/AA00026325/00001/citation, accessed on July 1, 2022; “Clayton Clarke Off to School in New Orleans,” Panama Tribune, February 15, 1948, 6, Biblioteca Presidente Roberto F. Chiari del Canal de Panamá Archives.

- “Latin American Schools: Geared to Children’s Future,” Panama Canal Review (December 7, 1962), 8, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-W79-d63f86b2ff514d4f3eaa6260af9363b4/pdf/.

- “Former Local Rate Playground Athletes Star in Bol. Games,” The Panama American, December 15, 1951, 10, https://dloc.com/AA00010883/01325/zoom/9; Cat Ariail, “Between the Boundaries: The Athletic Citizenship Quest of Carlota Gooden,” Journal of Sport History 44, no. 1 (2017): 1–19.

- “Petit Needs One Win for Olympic Nod,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), December 31, 1949, 16.

- Corinealdi, “Envisioning Multiple Citizenships,” 87–106.

- Stephen Frenkel, “Geographical Representations of the ‘Other’: The Landscape of the Panama Canal Zone,” Journal of Historical Geography 28, no. 1 (January 2002): 85–99.

- “5 Foreign Stars Call H-T ‘Great,’” Austin American-Statesman, October 15, 1955, Huston-Tillotson University Archives, Austin, Texas.

- “Petit Installed as President of Alpha Fraternity,” Unknown Publication, October 24, 1974. Courtesy of personal archive of Andrea Petit, daughter of Archile Petit.

- Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries (House), Panama Canal Miscellaneous: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on the Panama Canal of the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, House of Representatives, Ninety-Fifth Congress, First Session, on C.Z. Biological Area Authorization, H.R. 3348, March 22, 1977, Problems of Canal Zone Residents and Employees, April 12, 13, 1977, Balboa, Canal Zone, January 1, 1977, 107, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-Y4_M53-6ce539a27f956f470bb8fccde84c0f47, accessed February 10, 2023.

- Corinealdi, Panama in Black, 146.