“These women were engaged in an ongoing, material experiment of how to be together and live together in their world, at the Crossroads.”

Mamie Barnes was the first Black woman to own land at the Crossroads. Her lot was right below the four-way stop, down the fork and to the left, directly in the sun, in God’s spotlight. Her neat, white shotgun house had a white, wooden screen door that led to a screened-in porch and a white, wooden porch swing—the perfect prelude to the inside—and all around us was beauty: pink roses and petunias, ripened okra and purple eggplant, collards and cucumbers, stems crisscrossing, like braided hair.

Inside we sat on her red sofa, planted our feet on the beige linoleum floors, and prepared to talk about rural Black women’s beauty practices during the early twentieth century—hairstyling in particular. I was eager to drown out the sounds of Steve Harvey’s Family Feud and the box fan blowing in the background, but no matter the topic, the time or the place, when “Steve Harvey” was on, the women I interviewed at the Crossroads neither turned off the TV nor lowered its volume.

“The hair.” Mamie, my grandmother, always began our conversations by stating the subject, as if to remind both of us of the matter at hand. “Now, when I was little,” she said, “I do remember that Mama couldn’t comb my hair. I had real thick hair.” She elongated the real, emphasized the thick. “And Mama said she’d take a fork and straighten it out where she could plait it. And then she—” Mamie paused to reflect. “I don’t know what come of it, but I had hair.”1

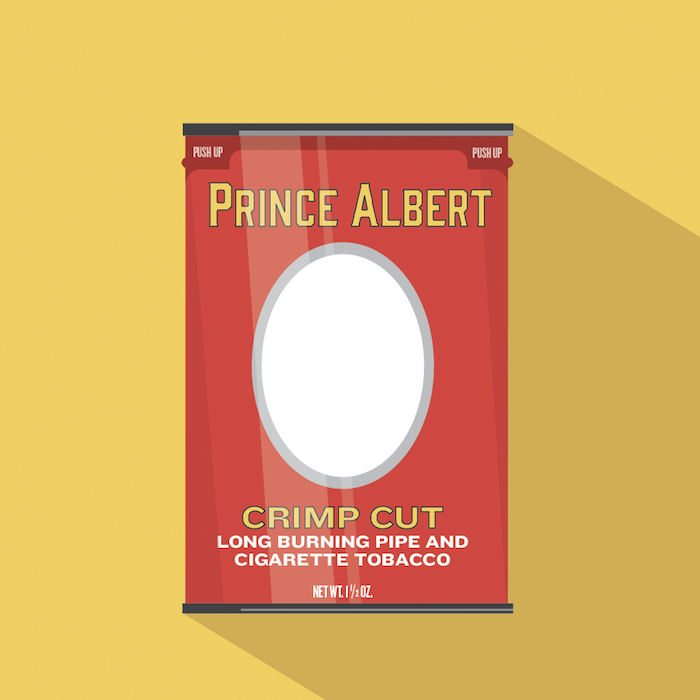

“Now when we got big-sized,” Mamie continued, “we would take a Prince Albert can, get the bottom off it and the top, and spread it out. Cut them things with the scissors and wrap them in some brown paper. And take your hair and put it in there, roll them up, and you’d be walking around with a head of tin cans.” I laughed silently, and she went on to explain: “And that morning, you’d take them out and comb them. You had curls,” she said. “Kim, that was the awfullest thing—curls.” Awful was a surprising word to use, I thought to myself, because from what I knew about these women now, I’m sure back then they thought they were looking good.

“So what was the brown paper for?” I asked.

“To wrap ’em up,” she replied, “wrap the tin up. The little strip what you cut off the tobacco can, you had to put it in the paper and wrap it up like you rolling a cigarette. . . . So you wouldn’t cut your hair,” she added for clarification. “Yes! That’s what we did,” Mamie said. “And then for greasing the legs, we had to use some lard. When we were going to church, I reckon we smelled like cooked meat.”

I was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi. I like to tell people that I was brought up between two worlds. I spent my weekdays in Jackson, the “urban” South, surrounded by family, school, and neighborhood friends. Then, like many other children who grew up in “the city,” on the weekends, I went “home,” to the place where my mother was from, where my grandmother Mamie lived—the country. Because my aunt ran the Crossroads Store—an “old country store” by day, café by noon, and juke joint by night—the Crossroads that I knew as a young girl was the Crossroads of stories, storytelling, and the blues.

Friday nights were for winding down from the workweek. My aunt would always take the party back to her house, where fried catfish was sustenance; Johnny Taylor provided the soundtrack; and working-class Black men with gold teeth and gators put on the show. What ended on Friday night would continue the next. Saturdays at the Crossroads smelled like perfume, whiskey, and chicken wings, like Black folks living as free as they could in the country South. People came and went, dipped out of pots of pig’s feet, filled to-go plates with neckbones, drank Crown Royal, and laughed loud until the sun set. And when the night sky was dark and blue, it was always the lightning bugs and Latimore, Marvin Gaye under the moonlight.

Sundays were reserved for the real grown folks—the elders—whose blues aesthetic shown through in the stories they told, after church, over plates of purple-hull peas and eggplant and porkchops, about “making do.” Indeed, while the blues is about Black folks reckoning with pain, oppression, and dispossession, and finding ways to make that reckoning livable and pleasurable, making do, or “makeshifting,” is, too.

My interviews examine how makeshifting includes Black women’s logical, material, and temporary responses to discrimination, oppression, racism, or lack. Makeshifting requires patching and piecing, and also requires Black women to view objects as multifunctional; that is, objects meant for one domain will almost always overlap with or be utilized for another. It is time-consuming—an arduous, laborious process that requires Black women, especially, to imagine, conceptualize, and create, again and again. But it is also provisional, meaning that though it provides temporary remediation to forces of injustice and constraint, it can never permanently erase them.

Since makeshifting is provisional, it is also cyclical—a process that requires Black people to constantly develop and imagine material strategies, methods, and tools to overcome structures of inequality in America, generation after generation. Black elders at the Crossroads passed stories around the table like they passed the offering plate between pews, and while they often reminisced about the days of working in fields and in kitchens, the consistent stories were always the ones about how “we took this and made that,” how “we made a way out of no way,” how “we survived,” how “we made do.” These stories about makeshifting are less visible to and present in the archival record. Because makeshifting was simply a way of navigating daily life and was not seen as anything to “celebrate” or preserve, stories about it were rarely collected or recorded, but they were most central to the lived experiences of rural Black folks. These stories also cast new light on unexplored aspects of daily life in the rural, Black South, and I noticed that it was the making, the makeshifting, and the material that served as quiet ways for rural Black women, especially, to reclaim a measure of control over their lives despite the economic conditions of sharecropping and the social conditions of Jim Crow.2

The consistent stories were always the ones about how “we took this and made that,” how “we made a way out of no way,” how “we survived,” how “we made do.”

I wanted to know more about the creative and material worlds of the Black women who worked as sharecroppers and domestics at the Crossroads during Jim Crow, so I created an oral history project to address the ways in which Black southern women have represented—in material form—their social, cultural, and historical experiences. In this contemporary moment, where Black people are constantly having to “shapeshift,” render themselves visible (“Black lives matter”), and construct alternate ways and aesthetics of being, I wanted to both examine and understand the creative strategies the Black women who lived in a place I’ve known all of my life employed to reclaim Black life in America, past and present. How would the women at the Crossroads describe those everyday spaces of meaning-making that they enlivened and invented during Jim Crow, now? What was the potential for the Black women at the Crossroads to inform and transform contemporary theory through their memories of life in the Jim Crow South? What tools had these women used to move through the world, and what could I learn from them? I found that they used material objects—for instance, repurposed Prince Albert tobacco tins as hair rollers, flour sacks as dresses, and Sears Roebuck catalogs as wallpaper—and engaged in makeshifting, to organize the logics of culture and community, to reimagine their circumstances, and to resist in the face of poverty and racial, class, and gender discrimination during the early twentieth century.3

The crossroads—a small, predominantly African American community—sits in the northeast corner of Claiborne County in rural Reganton, Mississippi, sixty miles south of the Delta. The town was named in 1888 for the Regan family, and where all roads meet—at the intersection of the cities of Jackson, Port Gibson, Vicksburg, and Utica—a cross forms, giving the town its nickname. In the 1930 Rand McNally census, Reganton is listed as being “formed from plantation,” meaning that enslaved laborers settled in the area and continued to live there years after emancipation. The Black women I interviewed were born between 1927 and 1947 and most are descendants of enslaved laborers who lived and worked on Homewood and Regan Island cotton plantations at the Crossroads. While these women were birthed into the arms of freedom, sharecropping “replaced slavery as the main mode of labor in the rural South after the Civil War” and, according to historian Robert Hunt Ferguson, “laid the groundwork for its wretched sibling, Jim Crow.”4

The women I interviewed held, at one point or another, one or both of those “two seemingly ironic positions” which political theorist Shatema Threadcraft (quoting labor historian Jaqueline Jones) describes in Intimate Justice: The Black Female Body and the Body Politic: “First, they were expected to perform exploitative productive labor typically reserved for those who possessed masculine embodiment, an exception that diverged significantly from dominant conceptions of ‘women’s work’”; and “second, they were considered suitable for a form of marginal, often backbreaking, and always exploitative women’s work—work within the white intimate sphere, and work that served to meet the bodily needs of white families at the expense of care for the bodily needs of their own.” For these reasons, I chose to focus specifically on the interior worlds of rural Black women, who worked in fields and white women’s kitchens, cared for their children and others’, were cooks, dressmakers, seamstresses, tailors; cleaned, ironed, pressed, washed, folded; picked, hoed, shucked; and had to find ways of making, doing, and being, for themselves and members of their community, despite being overworked and underpaid, weary and worn. The Black women at the Crossroads were, and remain, integral to the survival of these communities, and their oral histories serve as invaluable material for understanding the ways in which these women navigated racism, discrimination, labor exploitation, and poverty during the early twentieth century.5

The majority of the women I interviewed were born or came of age during the Great Depression in America, and they were contemporaries of Jim Crow. As historian C. Vann Woodward wrote of this generation, “They grew up along with the system. Unable to remember a time when segregation was not the general rule and practice, they have naturally assumed that things have ‘always been that way.’” When I asked Leyria McGriggs how Blacks and whites interacted at the Crossroads, she replied, “Well, we never did know no white people. Nothing but Jake Hutchins. We never did go around ’em. There wasn’t no white people, nobody but Jake Hutchins ‘nem.” Here, Mrs. McGriggs took my question about interaction and transformed it into knowing, demonstrating how she and other Black women at the Crossroads charted degrees of Black and white engagement. She “never did know no white people” because Black and white people rarely interacted with one another outside of work during Jim Crow. Indeed, while she knew white people—she was aware of them, observed them, and worked for them—she rarely had meaningful relationships with them, seldom experienced them personally, and, as such, did not really “know” them.6

Another woman agreed that Blacks and whites “didn’t associate with one another, ’cause you know white folks didn’t fool with Black folks then like they do now, not unless they were working for them. Because you know, back then, most colored folks worked in white folks’ kitchen, you know? Helped raise their children and things,” she explained. “You had to go in the back door then, couldn’t go in the front door,” she added. Here, this woman indicates that while Black and white people were hardly companions or friends, they did engage with one another, and “knew” each other, through work. Black and white relationships were neither fluid nor dynamic; and when Black folks went to work in white folks’ kitchens and helped raise white folks’ children, they did it all by way of the back door.

Marie Davenport responded to my question matter-of-factly: “The relationship between Black people and white people at that time when I grew up, there was no relationship. You stayed on one side of the fence and they stayed on the other. There was sometimes respect, though, because they would say ‘hello’ to you, but when I say ‘respect,’ it was only respect because you stayed—you knew your place.” Here, the fence serves as a literal and metaphorical representation of Black/white interactions. As Ms. Davenport put it, “The only time we ever talked to white people is when [we] were going up to the store to buy something. Because my community was all African American. Ninety-nine percent, except this one store.”

While many women constructed the political, social, and cultural history of the Crossroads community on their own terms, others—especially those who worked as domestics—remembered the interactions between whites and Blacks as existing on a spectrum, with histories of white racial violence at one end and deeply personal relationships at the other. Mamie Barnes recalled a story that reflects these dynamics. “I had a boyfriend but he left here with a man,” the story began. Her boyfriend, a man named “Lennon,” was expecting a check in the mail, but had an unpaid debt with a white man. Lennon had instructed Mamie to get his check out of the mailbox when the mailman delivered it. Mamie got the check “but then the white man… come down there, gone take the check. And Lennon had the check.” The two men stood in the yard arguing about the money. “Lennon’s mama was crying, she was down on the ground, ‘Please give it to him!’ Lennon took the check out his pocket, threw it on the ground, said, ‘Now, there it is! You pick it up I’ll break your neck.’”

“You pick it up I’ll break your neck.”

“And Ms. Nancy (Lennon’s mother) was crying, she was hollering, that was a sad day,” Mamie explained. “And that old white man was scared to pick it up,” she continued. “He went on back, got some more white folks. When he got the folks and come back, Lennon was gone.” Lennon left before nightfall and caught a bus to Michigan. He and Mamie would never reunite. She noted later that Lennon left in fear that he would be lynched.

Mamie and the other Black women at the Crossroads during Jim Crow lived under the constant threat of white vigilante violence, but they were bounded by the confines of race, place, and gender. They had to take care of white women’s household chores and their own; raise white children and their own; look after siblings and husbands; do hair, clean houses, sew clothes, go to church; as well as work in the fields. Their embodied intersectional identities meant that their lives reflected the pressures of gendered divisions of labor, Black social reproduction, and domesticity. Unlike Lennon, they could not just up and leave. Their presence at the Crossroads was binding, mandatory, and essential for the daily operations of the community. And because these women had established a level of trust with the white people they worked for, especially those who worked in white homes as domestics, they were not easily replaceable. Lennon stood his ground with the white man but had to flee the Crossroads, leaving Mamie behind to work and pick and makeshift and make do.

Because Mamie Barnes worked as a domestic, she also spoke about the deep, meaningful relationships she had with some white families who also lived and worked in the community. In the rural South, historian Mark Schultz writes, cultures of localism and personalism “allowed for the toleration of widely varying modes of race relations among different individuals.” Indeed, where the races mingled, as historian Melissa Walker explains, “a highly articulated racial etiquette governed personal interactions” and in the rural South, this racial etiquette was “more behavioral than spatial.” Historian Grace Hale explains:

Since southern Black inferiority and white supremacy could not, despite whites’ desires, be assumed, southern whites created a modern social order in which this difference would instead be continually performed. For whites, this performance, in turn, made reality conform to the script. African Americans were inferior because they were excluded from the white spaces of the franchise, the jury, and political officeholding. They were inferior because they attended inferior schools and held inferior jobs.7

The Black women at the Crossroads attempted to respond to this perceived inferiority by assimilating to a measure of taste that was prescribed by white elites. The women from the Crossroads frequently mention whiteness “as the standard of beauty back then,” or, in the words of Marie Davenport, “whiteness was all we saw.” These women came of age at a time when respectability was a revolutionary act and served as a measure of protection. However, their memories of makeshifting allow us to reframe these notions of assimilation and respectableness. For them, making and repurposing objects was about reimagining and then physically making a world where there was no outside, where there was no difference, where there was no counter-aesthetic. The women I interviewed narrate the ways in which they were engaged in an ongoing, material experiment of how to be together and live together in their world, at the Crossroads.

Many of these Black women still live at the Crossroads. They never migrated North; they survived Jim Crow and segregation; and they do not own more than the lots on which they live, but they found ways of making, doing, and being, and have made their lives significantly meaningful through these acts. And they live on to tell the stories of how they “made a way out of no way,” or in their case, “made do.” This makeshifting is at the core of these women’s experiences, and it demonstrates how their demands for racial equality were always linked to their material circumstances.

Makeshifting at the Crossroads

For Black women like Mamie, everyday activities like fixing hair, especially in the absence of commercial products, required a creative engagement with objects. First, these women took everyday eating utensils—forks—and used them to detangle their hair; to free it of clusters, knots, and kinks; and to get it to a place where it could be parted, rolled, and styled. Because tin is a soft, highly workable metal, it was the most suitable material for the Black women at the Crossroads to cut, fold (they could bend each end of the tin toward each other while in the hair, securing the roller), or shape, as necessary. Brown paper bags were easily accessible, could protect the hair shaft from being cut by the tin, and could absorb excess moisture, especially from the lard. The women would have previously used lard to moisturize their hair, and once the hair had “set,” or was fully dry, and the rollers removed, the women would emerge with a head full of shiny curls.

There is complicity in a tin can. They pass from hand to hand, pocket to pocket, man to man, and as much as these cans hold an identity, they also supply one. For the Black women who lived and worked at the Crossroads, the tin cans—and the entire process of fixing hair—evoked the very images these women wished to shed. In other words, coincidentally, tobacco, slavery, and whiteness (symbolically) emerged in Black women’s makeshifting practices. For instance, the tin cans, which were often used after they were discarded by both Black and white men at the Crossroads, sat at the intersection of waste and roller, trash and styling tool, and while they were useful in curling hair, they also held the mahogany-colored, burley-based, air-cured tobacco that caused disease and sustained plantations during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in North America. These tins held the same tobacco that delivered subtle notes of molasses, a colonial cash crop that was grown by—and traded for—African slaves. And they always featured the name and likeness of England’s Prince Albert (the father of King Edward VII) on their front, a man who personified the fashionable, leisured elite and whose image invoked the world of white nobility. The brown paper bags that the Black women at the Crossroads used as both rollers and as hair coverings evoke memories of toting paper bags of groceries from the store to one’s house, or to the house in which one was working. They conjure images of food and abundance (or the lack thereof), and of balancing bags on the long trip home. What did it mean, then, for the Black women at the Crossroads to take these objects and transform them for the purposes of beautifying themselves? Makeshifting and resilient creativity served as the means by which these women defined freedom for themselves in the absence of sociopolitical freedom during the Jim Crow era.

Makeshifting and resilient creativity served as the means by which these women defined freedom for themselves in the absence of sociopolitical freedom during the Jim Crow era.

The women at the Crossroads made it very clear that their preoccupation with the comfort and livelihood of white families did not mean that they did not think creatively and intuitively about their own aesthetic worlds. They include makeshifting in their cultural toolkit—what sociologist Ann Swidler defines as the “habits, skills, and styles from which people construct ‘strategies of action’”—to demonstrate how they transformed ordinary objects—like Prince Albert tobacco tin hair rollers—into material necessary for navigating daily life. In the stories they tell, the Black women at the Crossroads imbue objects with rich histories of creativity and innovation, and situate them, in the present, as sites of Black communal and cultural memory and social and political struggle.7

As Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps write in Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, for Black folks, especially Black southern women, hair has always been both a hotbed of contention and a place of creative freedom—a source of pain and punishment for some, community and continuity for others, but always complex, contested terrain. Working in kitchens and fields—picking cotton, harvesting sorghum, chopping cane—required an exhausting degree of bodily labor. To come home and wrestle with hair only added to the discomfort of already battered and worn bodies. Objects and makeshifting, then—despite requiring another type of (creative) labor by these Black women—lessened, in many ways, their physical pain, and not solely for themselves, but for other Black women in the community, too.9

Hair functions as an identifier of ethnic and geographic origins, gender, religious beliefs, social status, social trends, and more, with “kinky” hair most often associated with African Americans and straight hair with whites. While few interviewees commented directly on the racial politics of hair in their community during the early twentieth century, some did, highlighting the ways in which Black hair was seen as deviant from a white standard of beauty and respectability. Marie Davenport recalled her grandmother who—like many other African Americans at the time—”did some extreme things to straighten the hair,” like mixing lard with lye to chemically alter its texture, making the hair straighter in appearance and texture. This concoction was developed by African Americans in the absence of commercial products like relaxers and wave sets.10

“That’s all we saw,” Marie Davenport explained. “You see, our role model in terms of… beauty was always the image of a white person. It was not the image of a Black person, growing up.” These images, Davenport explained, were propagated by catalogs, such as those produced by Sears, Roebuck & Co., the same publications that the Black women at the Crossroads often tore pages from and used to line the walls of their houses. For instance, a 1945 Sears, Roebuck & Co. advertisement for a Crowning Glory Cold Permanent Wave Set reads, “To have lovely wavy hair is the desire of every modern woman. Today science and modern methods have been combined to make this possible.” The ad continues, “Now you can give yourself a Crowning Glory cold permanent wave without heat or discomfort,” a feature that promised a very different experience from that of Black women who suffered serious chemical burns using lye. The product name is telling (and ironic) considering the importance of hair and hair care for African Diaspora women, and it reflects the explicit marketing strategies of the time. The ad instructed users to dampen hair with the Crowning Glory wave lotion, place entire head of hair in curlers, let sit for three hours, apply neutralizing lotion to each curl, and “you have beautiful soft curls to fashion in your favorite hair style.” The illustrations portray two white women—one in her “favorite short style” and the other in a “popular long bob.” In the ad, “lovely wavy hair” is associated with whiteness, femininity, and modernity; and those “beautiful soft curls” that the Black women at the Crossroads desperately tried to achieve with the Prince Albert tins and straightening combs, these women could obtain with very little discomfort.11

“That was what we saw when we got our TV, that’s what we saw in magazines—like, believe it or not, I grew up in Mississippi reading this True Story magazine, and this magazine had pictures of white people who had a beautiful home; they were pretty—when I say pretty, they had what we thought was pretty as an image, was the straight hair and white skin. So this was the image growing up,” Ms. Davenport explained.

Indeed, in the Jim Crow South, as historian Blain Roberts notes, beauty was “determined largely by the presence of a racial other.” The Crossroads women’s memories echo this assertion. For example, because their hair was coarser than white women’s, theirs needed to be “fixed.” But fixing hair—Black women’s act of maneuvering, manipulating, and/or transforming objects (tobacco cans), scavenged or otherwise, and residual matter (lard) into tools for styling hair; and Black women’s use of these materials to alter or fashion their hair for aesthetic, social, and/or political purposes—was less about emulating white women and more about using objects in the absence of commercial products to reimagine and remake themselves in the ways that they so desired—if only temporarily.12

Leyria McGriggs remembered this best. When discussing her memories of rural beauty culture, she stated, simply, “You had to fix your hair with them curlers so you could get ready and go to church.” Since the occasion was a special one—church—fixing meant straightening hair (with a hot comb) and using an object (a tin can/can curler) to style the hair. For Ms. McGriggs—who spent the earlier part of her life working as a sharecropper at the Crossroads and the latter part as a laundress for the Holiday Inn in nearby Vicksburg—those curlers gave her the means and the autonomy to style herself exactly as she chose, helping her to create, or recreate, her identity, if just for that Sunday. With her fixed hair, she could step away from the cotton fields, release the cloak of poverty, and present herself as a woman of dignity, pride, and substance. To fix her hair, then, was to also—albeit temporarily—fix her social position.

Forks, Brown Bags, and Beauty

While most of the women I interviewed remembered using tins and straightening combs to style their hair, some women recalled that the entire process usually encompassed a variety of options, including “the brown paper bag” method. Susie Snow described the process: “You straighten your hair outside with a straightening comb, and you make a fire and put it up in a Prince Albert can. And put it on the heat. Then you get some brown paper, and twist it, and part it—and if you wanted it curled, roll your hair.”

“And it would roll it?” I asked.

“Yeah, it would curl!” she replied.

As a follow-up question, I asked her how she made the rollers. “Would you cut the tin open or would you—how did you actually make them?”

“No, we never had no—we never cut up no can,” she replied. “Ours was just [a] brown paper bag. And then they finally started to making—I guess they made it all the time but we didn’t have it—they started making a roller ’bout this long.”

She held both index fingers out in front of her, about four inches apart, to indicate the roller’s length. “And it had a little piece of wire in it. And leather on the outside.”

“But you would get those brown paper bags, and roll them up—?” I asked.

“And roll your hair up,” she replied. “When you’d go to the grocery store, you’d save the bags.”

For Ms. Snow, the Prince Albert cans served as a curling stove. Since the cans were metal, they could withstand large amounts of heat; they were also pliable, which meant that they could be shaped as necessary; and once their tops were removed, the cans revealed openings the perfect length and width for holding hot combs, thus making them useful material for Black women’s hair-fixing. And because tin does not rust or corrode, the curling stove—like the curlers and the brown paper bags—could be reused, again and again.

As Mamie demonstrated, the brown paper bags were often used as a covering. They protected the hair shaft from being cut by the tin. However, in this case, she suggests that women who did not want to risk cutting their hair at all simply used the brown paper bags as rollers. The bags were easy to come by, and their strength and flexibility made them useful tools for rolling, styling, and manipulating hair. As she indicated, the bags needed only to be twisted, the hair parted and then rolled. Because the bags were brown, they could have also blended into the hair more seamlessly than a tin can, creating a more “natural”-looking aesthetic—versus, as Mamie describes, “walking around with a head of tin cans.” These object biographies underscore one of anthropologist Igor Kopytoff’s fundamental arguments: “that what is significant about the adoption of alien objects—as of alien ideas—is not the fact that they are adopted, but the way they are culturally redefined and put to use.” These object biographies serve as Black women’s way of creating a material lineage of resistance: their adaptation of discarded objects into useful material suggests that they saw enough value in southern Black life that they were willing to examine and redesign even scraps in ways that were accommodating and would help them lead meaningful lives.13

In a separate conversation with Mamie Barnes, she elaborated on her memories of using forks to comb and detangle her hair. “Well, I had a head of thick hair,” the story began. “It was so thick and nappy. So mama would straighten it. But we didn’t have grease to straighten our hair. She had to use lard. And she used to have a fork that she straightened our hair with.”

A fork?” I asked.

“A fork. Just like an ‘eating fork.’ She’d take that and straighten it. And then my hair was so thick, she would cut some of it out as she’d straighten it out.”

And Marie Davenport—who worked as a water girl in the cotton fields as a child, but who would go on to become a beautician herself—had similar memories: “My grandmother told me, when she was growing up, they used a fork that you eat with. They heated that fork up and brought it through the hair to straighten the hair. To make it easier to comb,” she explained. “Because the combs that I saw out there were—you couldn’t get that comb through the hair hardly. It was difficult.” Here, my interviewee was referring to fine-toothed combs associated with combing thin, fine hair, similar to those used as mouth harps, as opposed to wide-toothed combs or afro picks. For the Black women at the Crossroads to take these objects and adapt them for their own purposes, demonstrates not only their deep and creative engagement with such objects, but reveals how—in their makeshifting—Black southern women were symbolically transferring agency. By recasting objects, these women were reimagining and then recreating objects that would function for the purposes of meeting their needs, when they needed them to and how they needed them to.

Reimagining the Beauty Shop

In small towns across the rural South, usually on a Main Street, you will occasionally find a small hair salon nestled between houses, next door to an auto body shop, or sitting atop a hill. In Utica, Mississippi, The Pink Styling Salon sits at the corner of West Main Street. It is a narrow, pink house, with three thin, red columns, a church pew on the porch, and a paved walkway leading to the front door. Mamie Barnes remembered having to wait in a parked car in front of the salon while the white woman she worked for was serviced in the salon.

None of the women mentioned visiting beauty shops for getting their hair done. In the absence of physical beauty salons, the black women of the Crossroads created alternative spaces for black beauty-making. In addition to the yard being the central hub for doing hair, it was also suitable for building the fires that would heat the tin curling stoves. My grandmother and her cohort situated their make-shifting into communal, familial, and physical spaces for socializing and beautifying. They took their objects outside, creating their own “beauty shops.” In makeshifting and reimagining objects, the black women at the Crossroads had also reimagined a rural geography, and were in turn reorganizing the logics of culture and community.

Painter Clementine Hunter’s Brushing Her Hair, completed during the 1940s, serves as visual confirmation of rural black women’s beauty culture as it relates to their conceptualizations of space, community, and placemaking during Jim Crow. Hunter, a black self-taught visual artist and memory-painter who lived and worked on Melrose Plantation in the Cane River region of Louisiana, depicted black life in the American South during the early twentieth century. The focus of this painting is a lime green house with a black roof, turquoise-trimmed triple-paned windows, and three turquoise columns. Two women are at the top of a hill: the woman doing the hair is standing, using a utensil to brush and style—her orange dress the perfect contrast to a heather blue and peach Louisiana sky—and the woman receiving the service is seated, dressed in light blue. Three black children, nestled between large zinnias, are positioned below the women, facing the action. By featuring these women outside of the house, Hunter highlights black women’s intimate act of “doing hair” and the geographies—in this case, an imaginary one—that the material act engendered. In the absence of material spaces or beauty shops, Hunter’s black women, like the women at the Crossroads, often embraced the yard as the most appropriate social space for beautifying and primping. As Katherine McKittrick explains in Demonic Grounds, “‘saying,’ imagining, and living geography locates the kind of creative and material openings traditional geographic arrangements disclose and conceal.”14

As a makeshifting space—a place put to creative use—the yard itself becomes another “tool” that black women at the Crossroads makeshifted and transformed to navigate daily life in the rural Jim Crow South. The yard served functional needs (a space for cooking, washing, food production, including hog killings and porch sitting), and expressed values (resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, a sense of community), aesthetic preferences (the individuality of the owner), and in some cases spirituality (bottle trees and other yard fixtures were believed to destroy or ward off evil spirits). It was thus often swept, kept tidy, and beautified.

Mamie Barnes and the other black women who worked as sharecroppers and domestics at the Crossroads during Jim Crow shared with me their memories of making, doing, and being, and how they made their lives more meaningful through these acts. They had negotiated their collective identity through their communal representation of this shared experience. At the root of their oppression was always the prospect of their liberation; and through makeshifting, the black women at the Crossroads both demonstrated an extraordinary level of creativity in the act of living and found a way, through material things, to articulate the breadth of their humanity.

This essay appears in the Documentary Moment Issue (vol. 26, no. 1: Spring 2020).

Kimber Thomas is a native of Jackson, Mississippi. She earned her bachelor’s degree in English from Alcorn State University, her master’s degree in African American studies from the University of California, Los Angeles, and her PhD in American Studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is currently a CLIR postdoctoral fellow in data curation for African American studies at UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries.NOTES

- Interviews featured throughout this article included: Mamie Barnes, interview by Kimber Thomas, July 2017, Reganton, MS; Marie Davenport, interview by Kimber Thomas, April 2018, Washington, DC; Leyria McGriggs, interview by Kimber Thomas, August 2017, Utica, MS; Susie Snow, interview by Kimber Thomas, August 2017, Utica, MS. Many of the interviewees recalled having a head full of “long, thick hair,” especially as children, with pride. In Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, authors Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps quote anthropologist Sylvia Ardyn Boone, a specialist in the Mende culture of Sierra Leone, who argues that historically, among many African cultures, “a woman with long, thick hair demonstrate[d] the life-force, the multiplying power of profusion, prosperity, a ‘green thumb’ for raising bountiful farms and many healthy children.” Byrd and Tharps, Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2014), 4; Sylvia Ardyn Boone, Radiance from the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 186.

- The stories we “collect” about black life in the South often highlight more “formal” struggles for freedom, like sit-ins and marches, over everyday acts of creative resistance.

- Aimee Meredith Cox, Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 25.

- Mattie M. Wailes, census worker, “Reganton,” in Rand McNally’s Census, 1930–1940, “Claiborne County WPA Records” subject file, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS; Robert Hunt Ferguson, Remaking the Rural South: Interracialism, Christian Socialism, and Cooperative Farming in Jim Crow Mississippi (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), 3.

- Shatema Threadcraft, Intimate Justice: The Black Female Body and the Body Politic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 9.

- C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), vii.

- Mark Schultz, The Rural Face of White Supremacy: Beyond Jim Crow (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 6; Melissa Walker, “Shifting Boundaries: Race Relations in the Rural Jim Crow South,” in African American Life in the Rural South, 1900–1950, ed. R. Douglas Hurt (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003), 85; Grace Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: Pantheon, 1998): 284.

- Ann Swidler, “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies,” American Sociological Review 51, no. 2 (April 1986): 273.

- Byrd and Tharps, Hair Story.

- See Scott Lowe, Hair (Object Lessons) (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- Sears, Roebuck & Co. (New York: Chelsea House, 1945), 196.

- Blain Roberts, Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 7; for instance, Marie Davenport stated later in our interview, “I think what I learned from seeing my grandmother was—I thought she looked very nice and pretty because—she would put like white powder on her face and I don’t know if that was flour or what she used but dark as her skin was—and [on] her lips, she used berries—berries, you know, to put a little color on her lips.” My interpretation of her statement is that the white powder used here was less about my participant’s grandmother trying to look white and more about her using matter, in the absence of blush or rouge, to perhaps accent her cheekbones or to absorb some of the lard she likely used to moisturize her skin.

- Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 67. In “The Cultural Biography of Objects,” Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall suggest that object biographies examine an object’s life history in order to “address the way social interactions involving people and objects create meaning” and to understand how these meanings “change and are renegotiated through the life of an object”; Gosden and Marshall, World Archeology 31, no. 2 (October 1999): 169, 170.

- I highlight the work of Hunter here because she undoubtedly understood the materiality of everyday life for black southern women, as evidenced in her choice of subjects: fixing hair, picking cotton, washing clothes, going fishing, attending funerals, and trying to get to heaven—where, in her paintings, all of the black women had long hair; see also “Camitte the Hair-Fixer is Doing Ceola’s Hair,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, https://collections.lacma.org/node/2159009; Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 144.