This article appears in the Inside/Outside Issue (vol. 25, no. 2: Summer 2019) and has been condensed. To view the article in its entirety, visit Project Muse (link below).

This is more than one story. This is twenty-five years of narratives from farmworkers, mostly in the Carolinas, told in labor camp kitchens, on trailer porch stoops, and in small living rooms with fans whirring and children playing nearby.

There are stories of cultural celebration, of helping a sick co-worker, standing up to the crew leader, of wage theft and illness from pesticide exposure, of crossing the Rio Grande, of deportation threats. Stories of struggles and dreams, why people come and what they miss about home, what they like about farm work and what they want to change, how they carry on, and how they resist. These stories defy borders; they follow farmworkers from crop to crop, state to state, and country to country.

Student Action with Farmworkers’ interns and fellows collected these oral histories from 1992 to 2017. There’s more than one story of farmworkers in the southeast, more than one dream, more than one hope for change.

Aquí se presenta más de una historia. Estos son veinticinco años de narraciones de trabajadores agrícolas, su mayoría en Carolina del Norte y del Sur, relatadas en cocinas de campamentos de trabajadores, en entradas de tráileres, y en salas pequeñas con ventiladores zumbando y niños jugando.

Estas son historias de celebraciones culturales, de ayudar a un compañero enfermo, de defenderse del capataz, de robo de salarios y enfermedades por exposición a pesticidas, de cruzar el Río Bravo y de amenazas de deport-ación. Son historias de luchas y sueños, de las razones por las cuales vienen las personas y de lo que extrañan de sus hogares, de lo que les gusta del trabajo agrícola y de lo que les gustaría cambiar, de cómo siguen adelante y de cómo oponen resistencia. Las historias no tienen fronteras; siguen a los campesinos de cultivo a cultivo, de estado a estado, de país a país.

Participantes de los programas de Estudiantes en Acción con Campesinos (SAF) recopilaron estas historias orales de 1992 a 2017. Hay más de una historia de los trabajadores agrícolas en el sureste, más de un sueño, más de una esperanza para un cambio.

“ALGO QUE me gustaría cambiar . . . la paga, la paga, eso sí. Dice uno, pues ‘ta pesado y pa’ que le paguen a uno así de poquito. A cuarenta y cinco centavos, dice uno, tengo que hacer como 200 cubetas de camote para sacar 100 dólares . . . Y pues yo me imagino que pa’ hacer 500 cubetas en un día tienes que andar [se ríe] sin tomar agua casi . . . Yo no sé por qué el trabajo de campo, que es más pesado, es más mal pagado.”

—Yonatan, aparece en la foto. Foto y entrevista por Emma Cathell y Elena Pérez, Garland, Carolina del Norte, 2015.

“SOMETHING THAT I’d like to change . . . the pay, the pay, for sure. You’re like, this is hard, and they pay you so little. At forty-five cents, you’re like, I have to do 200 buckets of sweet potato to make 100 dollars . . . And I imagine that, to do 200 buckets a day, you have to [laughs] almost go without drinking water . . . I don’t know why farm work, which is harder, pays so much less.”

—Yonatan, pictured. Photo and interview by Emma Cathell & Elena Perez, Garland, North Carolina, 2015.

“SIENTO COMO si la maquina me va a cortar la mano, pero nada más trato de hacer lo mejor que puedo. No recibimos nada para mantenernos seguras, nada más tengo que estar atenta a lo que está pasando y cuidarme.”

—Mayra Cort, participante del programa Levante de SAF, 2007–2008. Aparece en la foto: campesino de Carolina del Sur. Foto por Lucero Galván y Guillermo Alvarado, 2012.

“I FEEL LIKE the machine is going to cut my hand, but I just try to do my best. We don’t really get anything to keep us safe, I just have to keep an eye on stuff and be careful.”

—Mayra Cort, SAF Levante youth member, 2007–2008. Pictured: South Carolina farmworker. Photo by Lucero Galván and Guillermo Alvarado, 2012.

“CREO QUE ES mejor estudiar que trabajar porque es tan duro . . . quiero decir, la escuela es difícil, pero si pones atención, no es tan difícil. En el trabajo agrícola, yo creo que trabajas más duro, y es al aire libre, y hace calor . . . y en la escuela estás adentro con el aire y todo.”

—Senayda, aparece en la foto (en medio). Foto y entrevista por Dulce Marin y Lisa Splawinski, John’s Island, Carolina del Sur, 2011.

“I THINK IT’S better to study than to work because it’s so hard . . . I mean, school is hard but if you pay attention, it’s not that hard. In farm work, I think you work harder, and it’s outside, and it’s hot . . . and in school you’re inside with the air and everything.”—Senayda, pictured in middle. Photo and interview by Dulce Marin and Lisa Splawinski, John’s Island, South Carolina, 2011.

“AQUI UNO trabaja más. Porque [en México] es diferente. Porque si anda uno en lo propio, se cansa uno y se sienta uno por ahí en la sombra, nadie lo anda presionando a uno. Uno mismo hace lo que puede hacer y ya. Si se cansa, pues descansa un rato y ya. Sigue otro rato. Hay horarios para entrar y salir. Anda uno más presionado aquí para trabajar. Ahorita, estamos entrando a las 7:30 y salimos a las seis de la tarde.”

—Miguel (seudónimo). Aparece en la foto: Campesinos de Carolina del Sur. Fotos (arriba y lado opuesto) y entrevista por Lucero Galván y Guillermo Alvarado, Monetta, Carolina del Sur, 2012.

“HERE, YOU work more. Because [in Mexico] it’s different. Because if you’re doing your own thing, you get tired and you sit down over there in the shade, nobody is pressuring you. You do what you can do, and that’s it. If you get tired, you rest a little bit, and that’s it. You keep going for a little while. There are schedules for starting and leaving. You’re more pressured to work here. Right now, we start at 7:30, and we leave at six in the evening.”

—Miguel (pseudonym). Pictured: South Carolina farmworkers. Photos (above and opposite) and interview by Lucero Galván and Guillermo Alvarado, Monetta, South Carolina, 2012.

Aparece en la foto: desconocido.

Pictured: unknown.

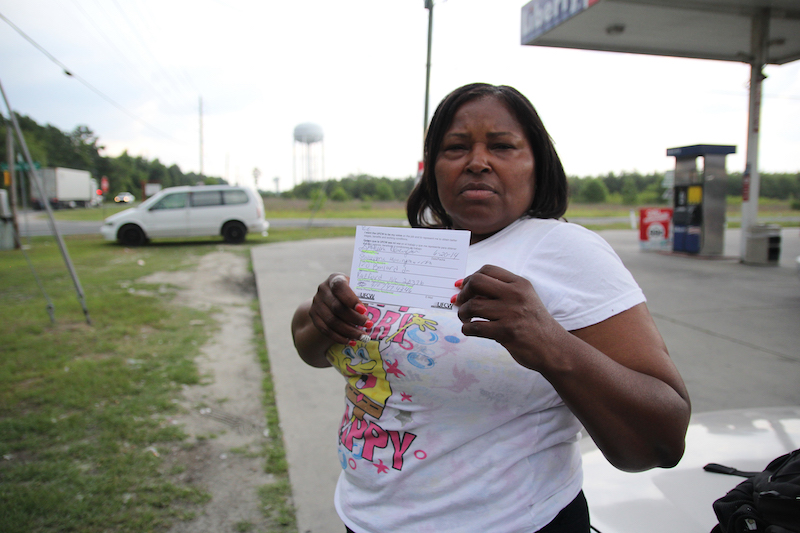

Elizabeth, aparece en la foto. Foto por Sarah Garrahan, Tar Heel, Carolina del Norte, 2014.

Elizabeth, pictured. Photo by Sarah Garrahan, Tar Heel, North Carolina, 2014.

“NADA BUENO va a ser fácil.”

—Ella, aparece en la foto. Foto y entrevista por Sarah Garrahan, Tar Heel, Carolina del Norte, 2014.

“AIN’T NOTHING GOOD come easy.”—Ella, pictured. Photo and interview by Sarah Garrahan, Tar Heel, North Carolina, 2014.

AQUI NO puedo hablar Purépecha. Casi no sé hablar español. Estoy agradecido por todo lo que me ha ayudado el Norte. Tiene sus altibajos. Sé que no es perfecto, pero a veces me da pena la gente aquí. No tienen amor, no saben cómo tener una vida espiritual. El trabajo artesanal que hago con cuentas es una manera de sentirme en casa aunque estoy lejos. Me siento debajo del árbol ensartando cada cuenta en el hilo que mi tía hizo con sus propias manos; viendo el mismo cielo que ella podría estar viendo y creando una obra de arte que se pasará de una generación a otra”.

—Noel, aparece en la foto (arriba y en el lado opuesto). Fotos y entrevista por Calyste Corrington y Rachael Mossey, Reidsville, Carolina del Norte, 2009.

“HERE, I’M not able to speak Purépecha. I can hardly even speak much Spanish. I’m grateful for all the North has helped me with. It has its ups and downs. I know that it’s not perfect, but sometimes I feel sorry for the people here. They don’t have love, they don’t know how to have a spiritual life. The beadwork I do is a way for me to feel at home even though I am far away. I sit under the tree stringing each bead onto the threads that my aunt made with her own hands; looking up into the same sky that she might also be looking at and creating a masterpiece that will be passed down from generation to generation.”

—Noel, pictured (above and opposite). Photos and interview by Calyste Corrington and Rachael Mossey, Reidsville, North Carolina, 2009.

“TRABAJAMOS ASI como familia. Porque aquí andamos en familia y todos los cinco andamos juntos. Yo no pude estudiar, pero a lo mejor [mi hijo] va a seguir estudiando. Y esa es la herencia . . . lo que le voy a dejar yo a él.”

—Francisco, padre del hijo en la foto y su cuñada. Foto y entrevista por Michelle Lozano Villegas y Kirby Erlandson, Hendersonville, Carolina del Norte, 2010.

“WE WORK together as a family. Because we’re here as a family and all five of us are always together. I wasn’t able to [study] but maybe [my son] will continue studying. And that’s my legacy . . . what I’m going to leave to him.”

—Francisco, father of pictured son and sister-in-law. Photo and interview by Michelle Lozano Villegas and Kirby Erlandson, Hendersonville, North Carolina, 2010.

“YO NO VOY a cualquier parte, a cualquier campo . . . yo voy con la gente, pues casi aquí hay muchos familiares de nosotros. Yo empecé llevándole a ellos los taquitos para que almorzaran, luego de ahí la gente quería y quería . . . Tuve que dar un precio económico.”

—Rosa María, aparece en la foto (izquierda). Foto y entrevista por Deborah Cramer, Chesnee, Carolina del Sur, 2007.

“I DON’T GO just anywhere, to any field . . . I go with the people, because, here, we have a lot of family members. I started by taking them taquitos for lunch and then people wanted more and more . . . I had to sell them for cheap.”

—Rosa María, pictured (left). Photo and interview by Deborah Cramer, Chesnee, South Carolina, 2007.

“SOLO SIGUE esforzándote. Sigue levantando la vista. Sigue mirando hacia adelante porque, si no aspiras a algo más, ahí mismo te vas a quedar.”

—Griselda, aparece en la foto (centro). Foto y entrevista por Eric Britton y Cindy Ramírez, Denmark, Carolina del Sur, 2013.

“JUST KEEP ON trying. Keep looking up. Keep looking ahead because, if you don’t aspire to something more, you’re going to stay put right there.”

—Griselda, pictured (center). Photo and interview by Eric Britton and Cindy Ramírez, Denmark, South

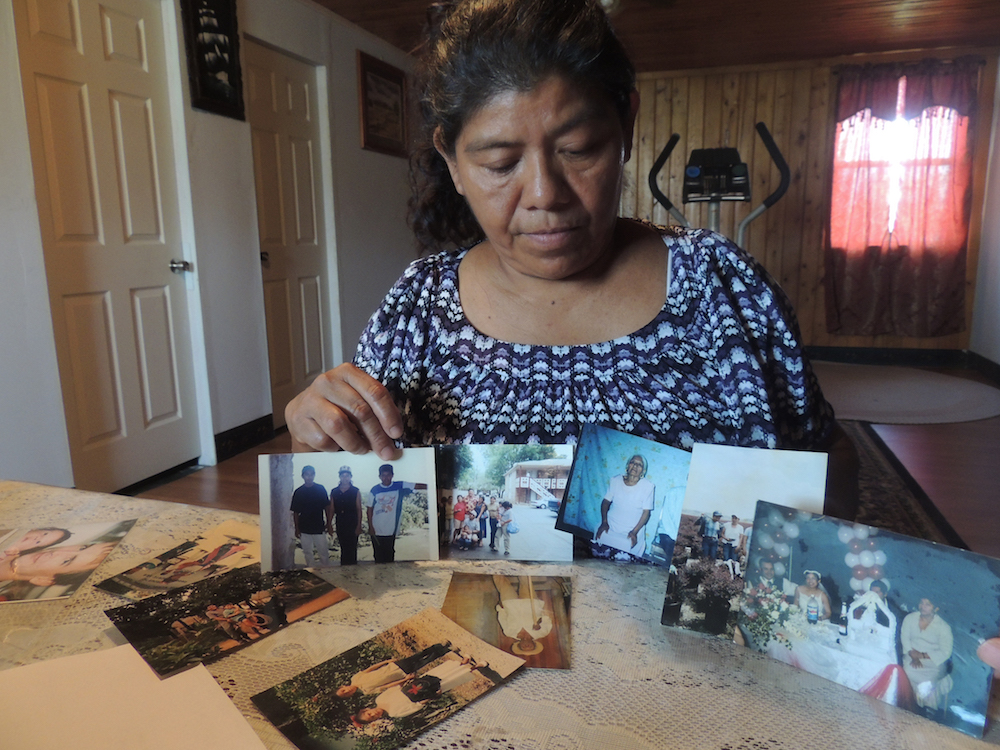

“ME MUDE a los ee.uu. cuando tenía veinticuatro años. Tardé cuatro días y tres noches atravesando el desierto. Uno sufre mucho caminando. Mi hija también cruzó el desierto andando. Yo personalmente no lo haría otra vez.”

—Carolina, aparece en la foto. Foto y entrevista por Emily Blackshire y Fidel Ruiz, New Zion, Carolina del Sur, 2015.

“I MOVED to the USA when I was twenty-four years old. It took me four days and three nights through the desert. One suffers a lot walking. My daughter also crossed the desert walking. Personally, I wouldn’t do it again.

—Carolina, pictured. Photo and interview by Emily Blackshire and Fidel Ruiz, New Zion, South Carolina, 2015.

“PUES MIRE, en realidad, nosotros venimos con la esperanza esa, pero, yo me estoy desengañando que hay mucha gente que topa con muy mala suerte, y así como llega a Estados Unidos, así se regresa. Uno viene buscando hacer dinero. Y es mentira, porque viene uno a sufrir peor que en su tierra . . . Uno deja a su familia sufriendo por tal de venir a ganar dinero aquí en los Estados Unidos, y no es cierto, como se lo imagina uno.”

—Miguel, Entrevista por Luis Mendoza, Burlington, Carolina del Norte, 1997. Aparece en la foto: desconocido. Foto por Laura Valencia, Fuquay-Varina, Carolina del Norte, 2009.

“LOOK, in reality we come here with hope, but I am realizing that there are a lot of people that run into very bad luck, and they return to their countries the same way they arrived in the United States. You come looking to make money. And this is a lie because you come to suffer worse than in your own country . . . You leave your family behind suffering just to come to make money here in the U.S., and it is not true, how you imagine it will be.”

—Miguel, Interview by Luis Mendoza, Burlington, North Carolina, 1997. Pictured: unknown. Photo by Laura Valencia, Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina, 2009.

This article appears in the Inside/Outside Issue (vol. 25, no. 2: Summer 2019) and has been condensed. To view the article in its entirety, visit Project Muse.