Three days after I turned eighteen, my mom, who was born in Jim Crow Florida, took me to register to vote at the same precinct where I grew up watching her vote. The experience taught me at an early age that voting was my birthright, something adults—and Black women in particular—did as good citizens. I loved the idea that on Election Day everyone is equal. It is our unofficial national holiday, our common language, regardless of race, age, gender, political party, ability, or state.

Like my mom, I have rarely missed an election. And like many Black Americans, I have had the experience of waiting hours to cast my ballot—an experience that is at once a privilege other people who look like me don’t always have and an indignity no American should have to endure. As a Black woman, a southerner, and an American, I have never been conflicted about my participation in our democracy and my role as a journalist; indeed, I have long believed that a healthy press and a healthy democracy are mutually dependent.

Four years ago, I helped to start a newsroom named for the amendment to the Constitution that enshrined the right to vote for some—but not all—women. The Nineteenth Amendment, passed in 1920, largely benefited the white women who sacrificed their Black sisters to gain access to the ballot. Women and many people of color would have to work twice as hard for their full access to the franchise, which came with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. More than a half a century later, the Vote stands as both the strongest and the most fragile symbol of our democracy.

This year, our democracy will be tested anew in our first election since former president Donald Trump falsely claimed both victory and widespread voter fraud. Much of Trump’s strategy relied on his attempt to cast many Black Americans as unqualified to participate in the electoral process. In addition to the Black voters Trump and his supporters tried to delegitimize, two Black women were singled out: Ruby Moss and her daughter, Shay Freeman, both poll workers in Georgia whose efforts were falsely cast as part of a sinister plot to rig the 2020 election. In the waning days of 2023, a federal jury held Trump acolyte Rudy Giuliani liable for his role in removing Moss and Freeman, ordering him to pay $148 million in damages, a decision he has appealed.

The Big Lie, which led to a violent insurrection by Trump supporters at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, is a fiction Trump continues to peddle as he campaigns for reelection. He does this while also facing criminal charges for his role in attempting to help overturn the results of the 2020 contest, and he will spend the 2024 election moving between the campaign trail and the courtroom.

Despite the events of the last four years, Trump entered the 2024 race as the Republican frontrunner and his party’s likely nominee. President Joe Biden is expected to again be the Democrats’ choice. But it is democracy that is on the ballot in November. The stakes of this election could not be higher—and I say that not as the perennial warning of political journalists, but as a citizen concerned about whether our politics as we have known them will continue as an essential pillar of our democracy or cease to function after this year. We know who the likely presidential candidates will be. The question we must ask ourselves as a country on Election Day is: who are we?

I am a native of Atlanta, now living in Philadelphia. These two cities have done much to help shape and perfect our union, and when I am in either of these places, I think often about what it means to be a citizen and who gets to be a full participant in our politics. I am honored to guest edit this issue of Southern Cultures, not only because of my deep reverence for the Vote, but because I believe our democracy has always run through the South. Our region of the country fought, bled, and died in the fiercest battles that won us full access to the ballot, helping to move America, for the first time, from an ethnocracy to a true, multiracial democracy. Our region of the country was—and is—also the site of some of the fiercest opposition to that proposition.

Half a century ago, the side of progress won out because of the diverse coalition of Americans committed to rejecting the antidemocratic politics of hate and exclusion. No less will be required to maintain democracy in this, our country’s hour of need. The South will once again lead by example in 2024—but what will we say? It is my hope that this issue, The Vote, can help us find our way forward, together. Collectively, the essays featured in these pages are a reminder of what was won, what we have to lose, and why what happens in the South continues to have implications for American democracy.

The battle between the forces encouraging voter turnout and those behind voter suppression will be waged again across our region, and the outcome will determine the future of voting rights, and, thus, the future of our democracy. Georgia, my home state, will play host to one of the major legal challenges facing the former president—a case that could hold him accountable for his actions during the 2020 election and thwart his attempts to regain power. I continue to assert that women will be the deciders of our election. In a year where many of my gender are contemplating the recent erosion of our rights that has determined our status as less free and equal than our mothers, how and whether southern white women have and will show up this fall—as allies or adversaries to democracy—and beyond is an urgent question at the heart of how we define identity politics.

For me, to be a southerner is to be a voter, and to be a voter is to champion the rights of all Americans. My hope for this issue is that you, my dear reader, join me in this work. This November, each of us has the duty to defend democracy at the ballot box. A robust defense of our values, those rooted in equal access and participation, in our hard-won right to vote, is what this moment and our democracy require. It is what we owe each other as southerners, and as Americans, as we continue to heal and perfect our Union.

Errin Haines is a founding mother and editor-at-large for The 19th, a news organization focused on the intersection of gender, politics, and policy. Haines has previously worked at the Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and Associated Press. A native of Atlanta, she is currently based in Philadelphia.

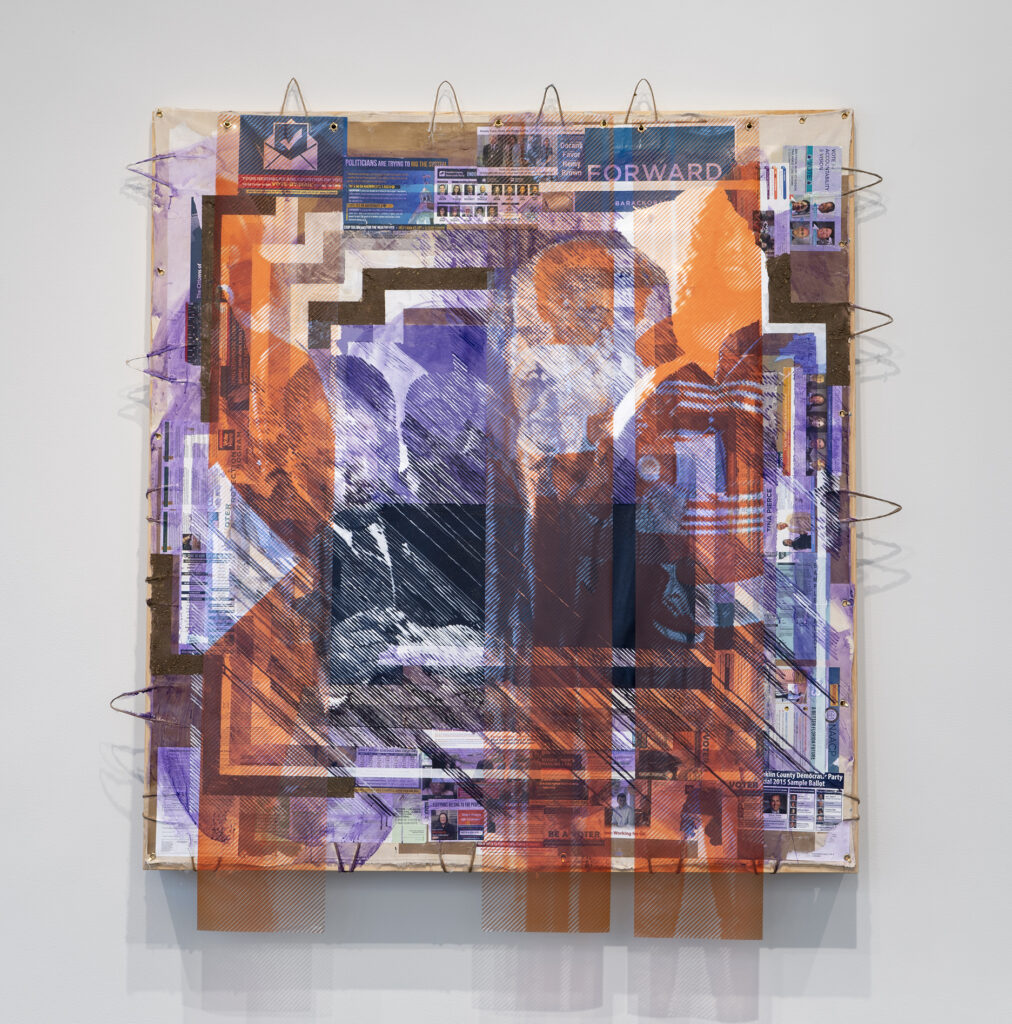

Header image: I Want To Be Free (O-H-I-O) (Bad Bargain) (2012 Cuyahoga County Voting Line) (2016 Butler County Voting Line), 2020, by Tomashi Jackson. Acrylic, Pentelic marble, Ohio Underground Railroad site soil, American electoral ephemera, and paper bags on canvas and fabric. 81¼ × 84 × 8 in. Courtesy the artist and Tilton Gallery, New York. Commissioned by the Wexner Center for the Arts at The Ohio State University.