When my father was a boy during World War II, he says, he was at the movies with his father one evening. The newsreel had just finished and the first chords of the feature’s soundtrack had begun, when the usher came down the aisle, shining his flashlight and saying my grandfather’s name. They followed him into the lobby where a policeman in uniform was waiting, eating popcorn out of a bag. My father was afraid.

“I thought Daddy was being arrested,” he says.

But instead the policeman said there had been an accident, and they got in my grandfather’s car and followed the policeman to the hospital, the same one where I was born, thirty years later, in a wing not then built. My father waited with the policeman while my grandfather disappeared down a hallway with a nurse. The policeman, still eating his popcorn between drags on a cigarette, talked to my father about school and baseball and a time he’d seen a man in a traveling show shoot sixteen peach cans off a woman’s outstretched arms with a .22 pistol. Afterward, she didn’t have a scratch on her, and each can had a perfect hole in it, right through the picture of the halved peach on the label, right where the pit would have been.

“Don’t that beat all?” said the policeman.

My father said that it did.

The policeman talked to my father about school and baseball and a time he’d seen a man in a traveling show shoot sixteen peach cans off a woman’s outstretched arms with a .22 pistol.

“What was the feature tonight, son? I’ve seen ’em all. I can tell you if you ought to be sorry you missed it.”

My father told him the name of the picture, which, all these years later, he says he can’t remember.

“I don’t know what he was going to say because that’s when Daddy came out holding Granny’s blue pocketbook, and I knew.”

I don’t know if he was looking for something of hers or if he was trying to find the exact spot where she died.

They went the next day and looked at the stretch of dirt alongside the railroad track where my great-grandmother had been struck down at dusk by a freight headed North. My grandfather paced up and down for what seemed to my father an hour, studying the ground, his hands in his pockets.

“I don’t know if he was looking for something of hers or if he was trying to find the exact spot where she died—a bloodstain or an indentation in the dirt, something like that. He never said a word. He’d walk down the track twenty or thirty yards, and then he’d come on back and walk up the track twenty or thirty yards. I can’t tell you how many times. I stood by the car—he had a ’38 Ford then—and I kept my eyes peeled for a train. I was petrified he was going to get run over, just like Granny.”

“Did he find anything?”

“No. After a while, he came back to the car, and we went home, and a day or two later, we had a funeral.”

“What year was that?”

“1944. I was seven.”

About Walker’s age. Walker, my son, is eight. He’s with me half the time and with his father and stepmother the rest. My parents are very upset by this division, but to me it seems about right. I’m only able to be a good mother about half the time. I try to make sure it’s on the days Walker is with me. I try to make sure there’s healthy food in the house; I shower and put on real clothes; I pick up after the dog in the backyard so that Walker can run around out there if he wants to, but he never does. Like me, he’d rather sit on the sofa together, reading or watching a movie. He likes being in the house.

It’s a nice, two-story house with wood floors, a butler’s pantry we turned into a breakfast nook, and a stained-glass window on the stair landing, a funny window with assorted garnet and emerald and amber and violet panes, and in the middle of it, a clear pane with a picture of a hedgehog who doesn’t look too bright. That window was why I wanted the house—too big for us even when we bought it—a rambly old house just right for a couple and two or three children and the occasional overnight company and a big party once a year that all your friends count on being invited to. I still love it and don’t plan to move, even though it’s too much for me and Walker and one geriatric dog that can’t make it up the stairs anymore. When something breaks or stops working—and something always does—it just has to stay that way until my father finds a Saturday when he can come over and take care of it.

When he came a few months ago to re-hang the screen door, he brought a bunch of boxes in from his truck and put them in the nearly empty back room that had been my ex-husband’s home office.

“What’s all this, Dad?”

“What’s all this? What’s all this? THIS, young lady, is the train.”

“The train?”

“My train. The train my father put together for me when I was a boy.”

“The train Joanna and I were never allowed to play with because we were girls?”

“Your grandfather asked you and your sister a hundred times if you wanted to play with it and you always said no.”

That’s not the way I remember it, but all I said was, “Do you think it still runs?”

“I’ll make it run, by God.”

He went back out to his truck and brought in this giant piece of plywood. Then another one. Then sawhorses. I saw that it was going to be a whole thing. A project. My mother was going to be calling Saturday afternoons when it started to get dark, wanting to know if my father was ever coming home. Joanna was going to pretend to feel sorry for me, but really she would be jealous the train had come to live at my house, and I would like it.

“And you won’t be mad if Walker messes it up? Or me?”

He leaned the plywood against the wall, careful not to scratch the paint. Took my hands, clasped them together, looked me in the eye as he kissed my fingertips.

“Butterbean,” he said, “I trust you.”

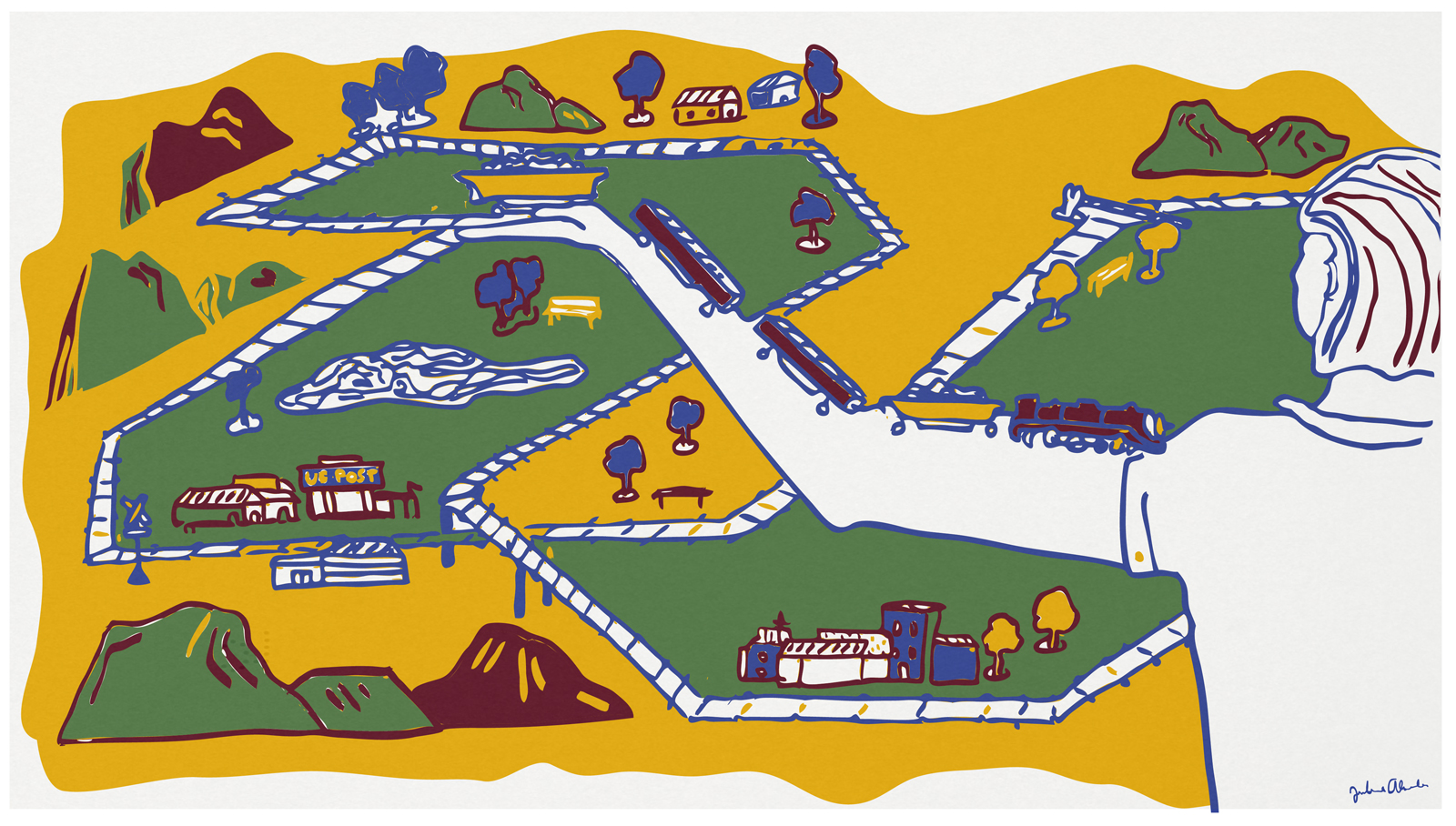

When we used to visit our grandparents, Joanna and I would sneak up to the attic to see the train. It was set up on a huge table, maybe ten by fourteen feet, that was covered with nubby dark green turf. There were hills and a silver lake, clumps of forest and a farm out from town with belted cows, speckled chickens, and a farmhand in overalls carrying a bucket of slop to the pigs. In the town was a depot and a main street with shops, a brick schoolhouse with a bell, a steepled white church. The clock at the top of the courthouse really ran, and out front, in a gazebo, young lovers kissed while kids ate tiny ice cream cones on a park bench. There was a family strolling across the street while a policeman stopped the traffic, five old-fashioned cars that looked like they’d be awful hot to ride in in the summertime.

Down the street was a black Scottie dog wearing a red collar and standing inside a white picket fence. The fence enclosed a yellow house and a yard where a brown-haired woman in a green dress and white apron was hanging out her wash, a wee basket of clothes at her feet. What was she thinking about, I used to wonder. What was it like in her little yellow house? I was dying to get in there and see. Did she have a pie in the oven? What kind? Was there a baby napping in a crib upstairs, all flush-cheeked and sweet, with its diapered butt up in the air? Was there, on the woman’s kitchen table, a miniscule book that she was eager to get back to reading before the baby woke up?

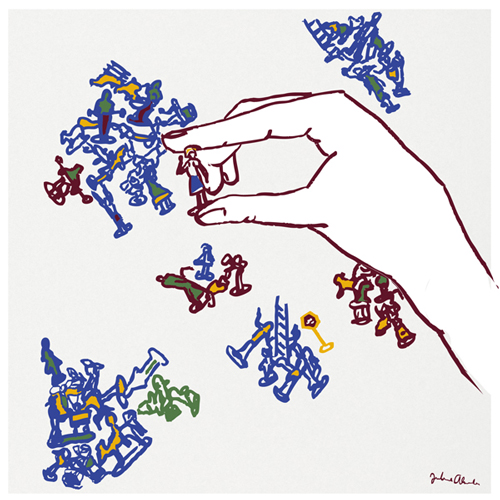

I found her the other day. It wasn’t a Walker day, and it wasn’t a work day, and I was aimless. I’d eaten leftover Thai curry, two cookies, and eight grapes for breakfast, and I was wandering around the house nursing my coffee, feeling sorry for myself for no reason I could put my finger on. I went into the train room, now nearly filled by the plywood table my dad had set up. The original layout from my grandparents’ attic had been thrown out long ago, so Dad was building a new one. While I was running errands one afternoon, he and Walker had unpacked the train cars and buildings and itty bitty people and lined them up on the shelves that used to hold my husband’s books.

My god, I’d forgotten how tiny the people were. I picked up the woman in the green dress and white apron. She’s only an inch tall and feels like a wooden matchstick between my fingers. When I was a child, I called her Mrs. DeVry. I had a little rhyme.

Oh, Mrs. DeVry, why do you cry, out by your line all day?

It’s Mr. DeVry, he said goodbye, off to the war far away.

When my dad showed Walker how everything was going to be laid out on the table, he shook his head and said he didn’t want it “all old school.”

“This is going to be the Mythology Express, Grandpa. Like, Mount Olympus will be over here in this corner, and the River Styx will be here, and Hades will be over here, with like—we can make some flames, you know, out of red and orange paper—and over here will be Delphi with a temple where people can get off the train and consult the oracle. Won’t that be awesome?”

Dad looked stunned, as he so often does when Walker speaks, and then he clapped Walker on the shoulder and said, “Well, Applejack, sounds like we better get busy.”

So we started building a world, the three of us. I painted columns for the temple, while Dad and Walker made mountains out of papier–mâché. We had the windows open and some Wilson Pickett on, and it was as fine a Saturday as I ever expect to spend.

Dad and I were disappointed, though, about the village being cast aside. I pleaded our case with Walker. I said there had to be a place where the mortals could live.

“Why do we even need mortals?” he asked.

“Because otherwise the gods wouldn’t have anybody to lord over.”

He said that was a good point and let us put the village at the far end of the table, more tightly clustered than it was in the old days, but at least it’s there, and Mrs. DeVry is back at the line, hanging out her wash. She has begun writing poems at her kitchen table in her spare time, so now I call her Mrs. Sylvia Anne DeVry, after Plath and Sexton, even though I know Mrs. DeVry will never be as accomplished as they were. But then you can’t expect that—she hasn’t had their advantages in life, now has she?

The other day, I sent Mrs. Sylvia Anne DeVry to the oracle. I walked her up the temple steps and stood her at the top, facing the door, and she told the oracle all about herself, a thing Walker would not sanction.

“Mom! People don’t tell the oracle stuff—the oracle tells them. They can just ask one question—that’s all!”

But Mrs. Sylvia Anne DeVry can’t avoid the confessional impulse. It’s too much a part of her nature. So she told the oracle all about her infidelities and her temper tantrums and the problems she has at her job that she had to get after her husband came back from wartime France a distant, ruined man. She told the oracle that once she even considered going down to the tracks and flinging herself on them, like the woman in the fat book sitting on her kitchen table, but of course she didn’t because how could a woman leave her children like that? Mrs. DeVry could never do that to her sweet baby, at home napping with his bottom in the air.

And the Oracle sayeth, with serious impatience, “I have many people to see, Mrs. DeVry. What is your question?”

Mrs. DeVry said, “What should my question be?”

And the Oracle sayeth, “Come back tomorrow.”

I wonder about that night when my great-grandmother was run down by that freight headed North. What was the train carrying? Supplies for the war effort? What was she doing out there, walking at dusk not far from the small house where she lived, a widow all alone? Was she crossing the tracks to visit a friend or maybe go to a store where she could buy Lucky Strikes or a can of beans? How did her blue pocketbook survive the accident, her wallet and handkerchief and unbroken glasses in a case, all tucked inside, all perfectly intact? Had her purse been thrown clear when she was struck by the train? Or did she set it down before walking onto the track?

And why, when my father came out into the bright lobby of the Varsity Theater and saw the policeman standing there, did he think his father had done something wrong and was being arrested? What had they just seen on the newsreel and would the movie they were about to watch have been enough to put that war news out of their minds for an hour or two? How could that policeman so blithely eat popcorn while he delivered such terrible, life-changing information?

And why did my grandfather keep that train set up in the attic until he died, a very old man, never having let my father take away what was rightfully his? Why did my grandfather sit up there alone and watch the train run round and round, winding through the hills and over the lake, past the farm and through the town, right by the yellow house where a pie is baking and a baby is napping and Mrs. Sylvia Anne DeVry, hanging out the wash, hears the train and mistakes it for the sound of a change coming?

This story first appeared in the 21c Fiction issue (vol. 22, no. 3: Fall 2016).

Julia Ridley Smith’s fiction has appeared in American Literary Review, Arts and Letters, the Carolina Quarterly, Chelsea, failbetter.com, the Greensboro Review, Inch Magazine, and storySouth, among other places. Her book and art reviews have been published in the Raleigh News and Observer, Art Papers, Southern Cultures, Our State, and elsewhere. She is a freelance copyeditor of academic books and currently serves as fiction editor for Inch Magazine. A graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Sarah Lawrence College, she lives in Greensboro with her husband and son.

Julienne Alexander is an illustrator and designer in Durham. Her work can be seen at www.yssrs.com.