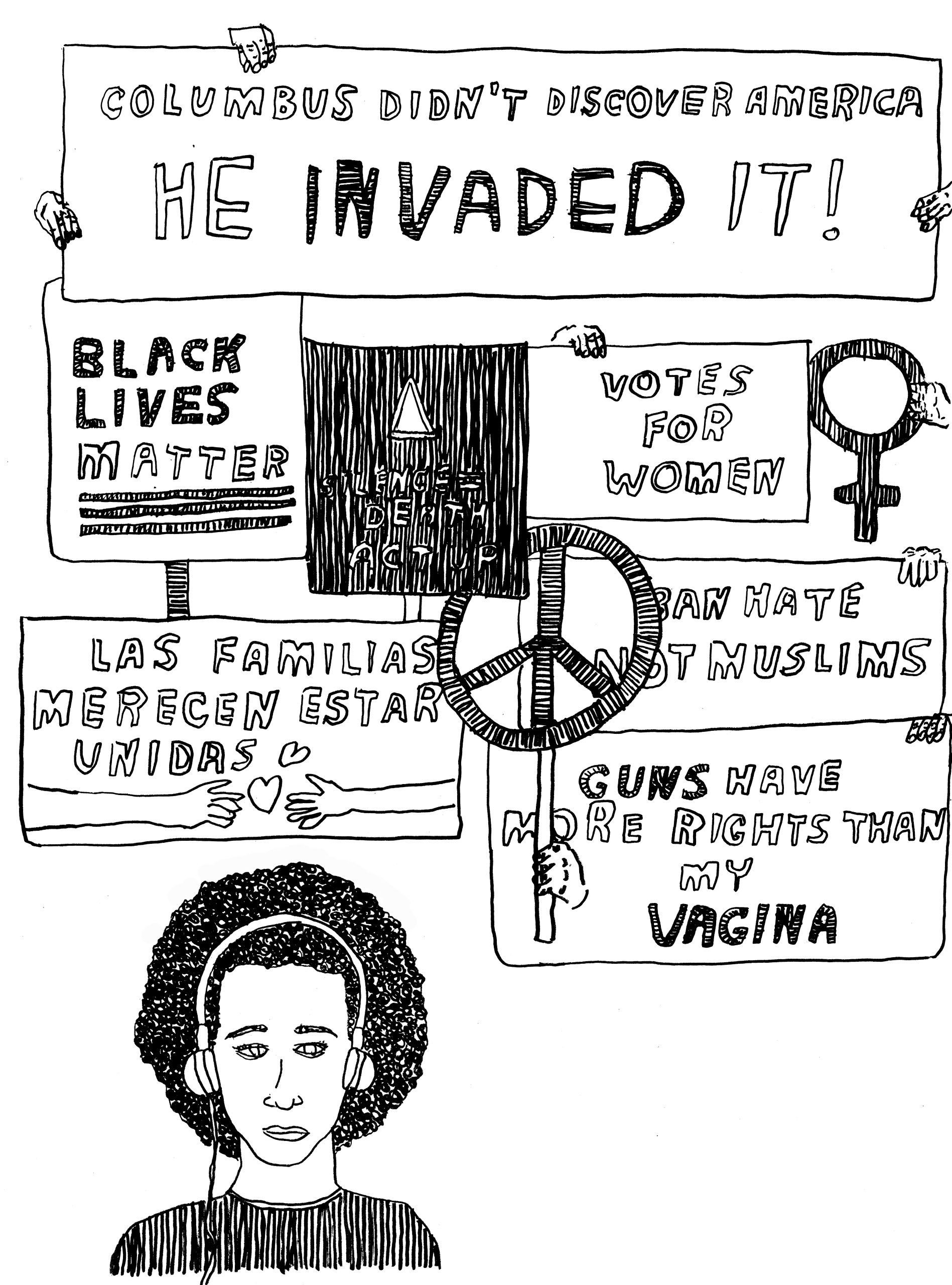

Hazel Dickens wrote “They’ll Never Keep Us Down” in 1976 for the soundtrack to Barbara Kopple’s Oscar-winning documentary Harlan County, USA. In Dickens’s lyrics, “they” are the rich men who prioritize profits over people, who “rob, steal, and kill” to maintain their power. Songs of protest have been around as long as humans have made music, and the “they” in these songs is not exclusively rich men but shifts according to the socio-historical context of the singer, or the needs of a community organizing around a common cause for whom the song provides a rallying cry. “They” can be any people, institutions, or structures that would oppress or otherwise subjugate another’s human rights. While protest songs are often communiqués for a specific audience, the power of the medium allows for transcendence of the subject and can lead to greater understanding of our shared humanity. We may not know who “they” are, but when we listen, we are energized, outraged, and connected.

We may not know who “they” are, but when we listen, we are energized, outraged, and connected.

The songs collected here span over a century, and the emotions and issues distilled in the music intersect constructs of race, class, sexuality, and politics: workers demand decent wages; farmers struggle against industrial agriculture; African Americans stand up for equal rights; prisoners lament the corruption of the criminal justice system; gender-nonconforming persons affirm their identities; artists reject the strictures of genre; immigrants and “others” have names. Not just a vehicle for airing grievances, protest songs act as focal points for engagement, catalysts for change, and inspiration for action. They offer hope and a vision of a better world. Like Allen Toussaint, we can hold Lee Dorsey’s words close, a mantra: “Oh yes we can, I know we can can, yes we can can, why can’t we? If we wanna, yes we can can.”