I met Margaret Walker Alexander in the fall of 1970 when I taught my first class at Jackson State University. She and I both taught in the English Department, and I will never forget a lecture that Margaret gave to my students on Zora Neale Hurston. She and Zora had traveled similar roads as southern Black women writers, and she recalled how she met Zora, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and other figures in the Harlem Renaissance. Her memories of Richard Wright were especially powerful, and I later reminded my students that Wright had lived on Lynch Street—the street that runs through the Jackson State campus—before he moved to Chicago.

Margaret also directed the Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People (now the Margaret Walker Alexander National Research Center). The Center featured visiting writers, such as Nikki Giovanni, and included a memorable program in which Fannie Lou Hamer both spoke and sang about her struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi.

While teaching at Jackson State, my former wife Josette Rossi and I rented a home on Guynes Street—now named Margaret Walker Alexander Street—in one of the first Black middle class neighborhoods in Jackson. Margaret lived several doors to the east of our home, and two doors to the west was the home where Medgar Evers lived when he was assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith as he returned home to his family on the evening of June 12, 1963. Our neighbors told us about that tragic night and how it was forever etched in their memory.

Margaret was one of three distinguished women writers who lived in Jackson at that time, the other two being Alice Walker and Eudora Welty. Alice was an aspiring young writer who had just finished her novel The Third Life of Grange Copeland, and Margaret encouraged her to pursue her literary career.

Margaret and Eudora often appeared together at literary events in Jackson, and they enjoyed a special friendship for many years as the First Ladies of Jackson’s literary world. They each had a circle of close friends in Jackson with whom they created literary salons where conversation and food were shared. Margaret loved to cook, and her journals are filled with references to food.

As a nationally acclaimed writer, Margaret was a celebrity on campus and an important role model for young African American women. Many students at Jackson State were the first in their family to attend college, and they were inspired by Margaret’s stature as a distinguished poet and novelist. Her first book of poetry, For My People, was selected by Stephen Vincent Benét for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition award in 1942. Margaret’s novel, Jubilee (1966), was based on her grandmother’s life as a slave and was often referred to as the Black response to Gone with the Wind.

When I taught at Yale from 1972 to 1979, I brought Alice Walker, Margaret Walker Alexander, and Eudora Welty to read and speak to my students. Margaret was an old friend of Charles Davis, chair of the Afro-American Studies Program, who also served as Master of Calhoun College, where I lived as a resident fellow. He hosted Margaret’s visit, and the text that follows was part of her presentation to Yale students at a Master’s Tea in Calhoun College in 1978. During her visit at Yale, she also reread letters she had written Richard Wright that are in Yale’s Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Donald Gallup, then curator of the Yale Collection of American Literature, met with Margaret and personally showed her materials in their Richard Wright Archives.

While directing the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi from 1979 to 1995, I worked with Margaret on a number of projects. Her poetry and fiction was featured in a series of anthologies of Mississippi writers that Dorothy Abbott edited while working at the Center. We also sponsored a lecture by Margaret when she signed copies of her book Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius: A Portrait of the Man / A Critical Look at His Work at Square Books in Oxford in 1988.

Throughout her life Margaret struggled with her own demons as she negotiated her roles as a mother, a teacher, a poet, a novelist, and a fearless voice for the history and culture of African Americans. From our first meeting in 1970 to her death in 1998, we shared a special friendship that I will always treasure.

From Margaret Walker Alexander’s Talk and the Subsequent Q & A

As a small child in the 1920s, I was very much affected by the Harlem Renaissance. As early as age eleven, I had read poetry by Langston Hughes. The president of New Orleans College, where my parents were teaching at that time, gave them a little booklet called “Four Lincoln Poets.” They brought it home and gave it to me. Langston Hughes first impressed me then. And when I was twelve, my parents brought home a copy of Countee Cullen’s Copper Son. My sister and I memorized both Countee Cullen’s and Langston Hughes’s verses.

Before I left home for Northwestern University, in that early period between age ten and seventeen, I saw and heard in lecture recitals Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson [the novelist, critic, and poet who penned the Harlem Renaissance’s seminal God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse], and Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes [who were both accomplished African American concert singers of the era]. These were significant events in my life. Also, Zora Neale Hurston [folklorist and Renaissance author of several works, including the highly influential novel Their Eyes Were Watching God] came out to the college in order to talk to my mother about folk materials in New Orleans, but my mother said she couldn’t help her—she studied under what they call the two-headed doctors of voodoo and hoodoo in New Orleans. Those of us who live there and have people ask us all the time about it always don’t know what they’re talking about. Either we feign ignorance or we are completely ignorant.

I remember [Zora Neale Hurston] because she had on a knee-length, sleeveless flapper dress and wore bobbed hair. I was impressed with how short her dress was.

I caught a glimpse of Zora, though I had no idea then who she was nor how significant she was. I remember her because she had on a knee-length, sleeveless flapper dress and wore bobbed hair. I was impressed with how short her dress was, because my mother’s dress was still well below her knees and didn’t come to her kneecap until much later.

I had never seen a real live poet before.

Langston Hughes’s appearance was a most exciting occasion. I felt partly responsible for his coming to New Orleans, because I’d told my parents they had to get him there. I had never seen a real live poet before. He came in February, shortly after his thirtieth birthday, and the college couldn’t promise to guarantee the $100 fee. But he made more than the $100, because he sold his books. He had already published then The Weary Blues, Fine Clothes to the Jew, and Not Without Laughter.

He and his manager-companion, who disappeared as soon as Langston arrived, were traveling through the South in what he termed “a beat up old Ford car.” But then Langston has given a description of that trip in his own autobiography, The Big Sea. He also remarks about seeing me and reading my poetry on that first visit.

He urged my parents to send me out of the South. And the next year, they did just that. On the advice of my freshman English teacher and on the basis of their own experience, they decided to send me to Northwestern.

But of all the figures in the Renaissance, I’m sure my idol was Langston Hughes.

I think it made all the difference in my life.

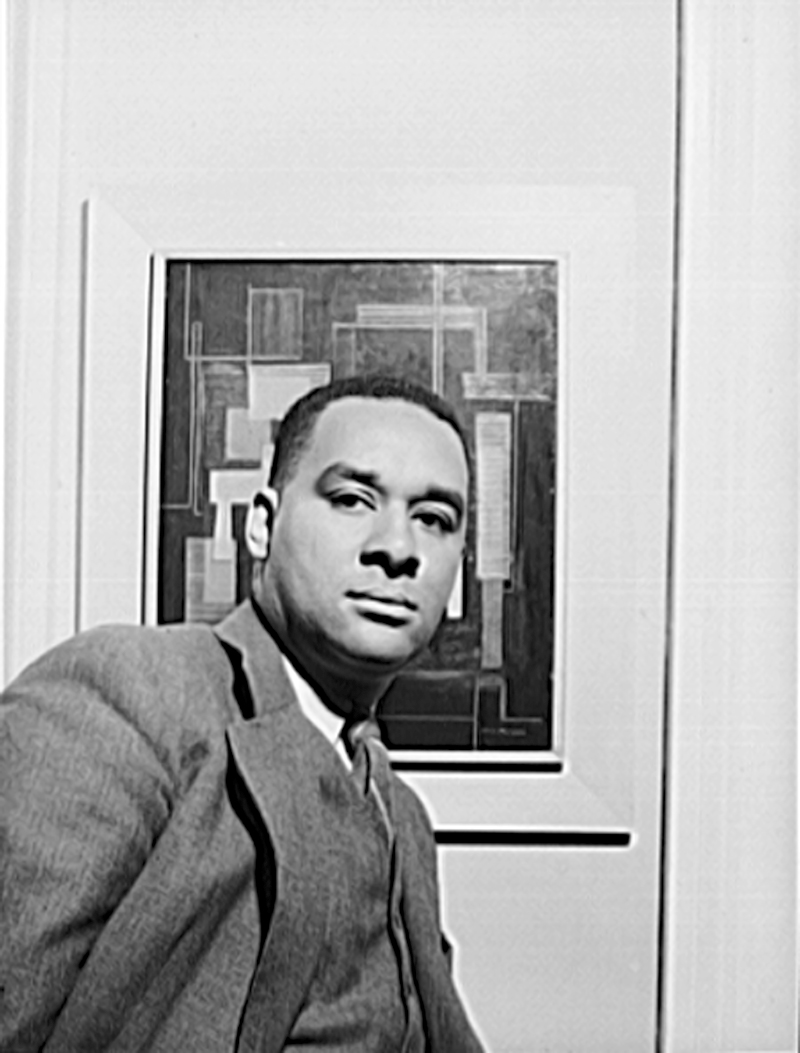

In February of 1936 I saw Langston Hughes again. This time in Chicago at the National Negro Congress. I had finished Northwestern by this time, and that day I saw Richard Wright [award-winning author of Native Son and several other books]. For the next three years, I saw Langston at least once a year when he came to visit in Chicago or just passed through. I also had the rare pleasure of seeing James Weldon Johnson in Chicago in the 1930s and shaking his hand at that time. Soon after that, in 1938, he was killed in a car accident.

On the Federal Writers’ Project, Richard Wright suggested that we go to see Arna Bontemps [a leading Renaissance poet and author of several books, including Black Thunder]. In New York, Wright also took me to meet Sterling Brown, who was then director of Negro Affairs for the New York Project [and a noted poet, author, and critic in his own right]. Later, in New York, when I was living there, and when it served as my lecture headquarters, I met and became acquainted with a very vivacious Gwendolyn Bennett [author of “The Ebony Flute,” a literary column in the magazine Opportunity]. When For My People was published [in 1942], I received letters of interest from two more notable figures in the Harlem Renaissance: Alain Locke [the writer and educator who mentored Zora Neale Hurston] and Countee Cullen [a prominent Renaissance poetry and prose writer of over twenty books]. Sometime early in the 1940s I visited friends in Lynchburg, Virginia, and there I met Anne Spencer [the first African American to have her work included in the Norton Anthology of American Poetry] and saw her in her garden.

I did not see the great sociologist, who was godfather to the Renaissance and also my benefactor through the Rosenwald Fund, until I was invited to Fisk University for the first time in the 1950s. There, Dr. Charles S. Johnson was the president. I went to dinner at his home and had the seat of the guest of honor at his right. I was too excited to speak anything but my inanities; but I was grateful for the opportunity, because the next year he was dead of a heart attack. He died in a train station, between trains, and on his way to fight against segregation and for school integration.

But of all the figures in the Renaissance, I’m sure my idol was Langston Hughes.

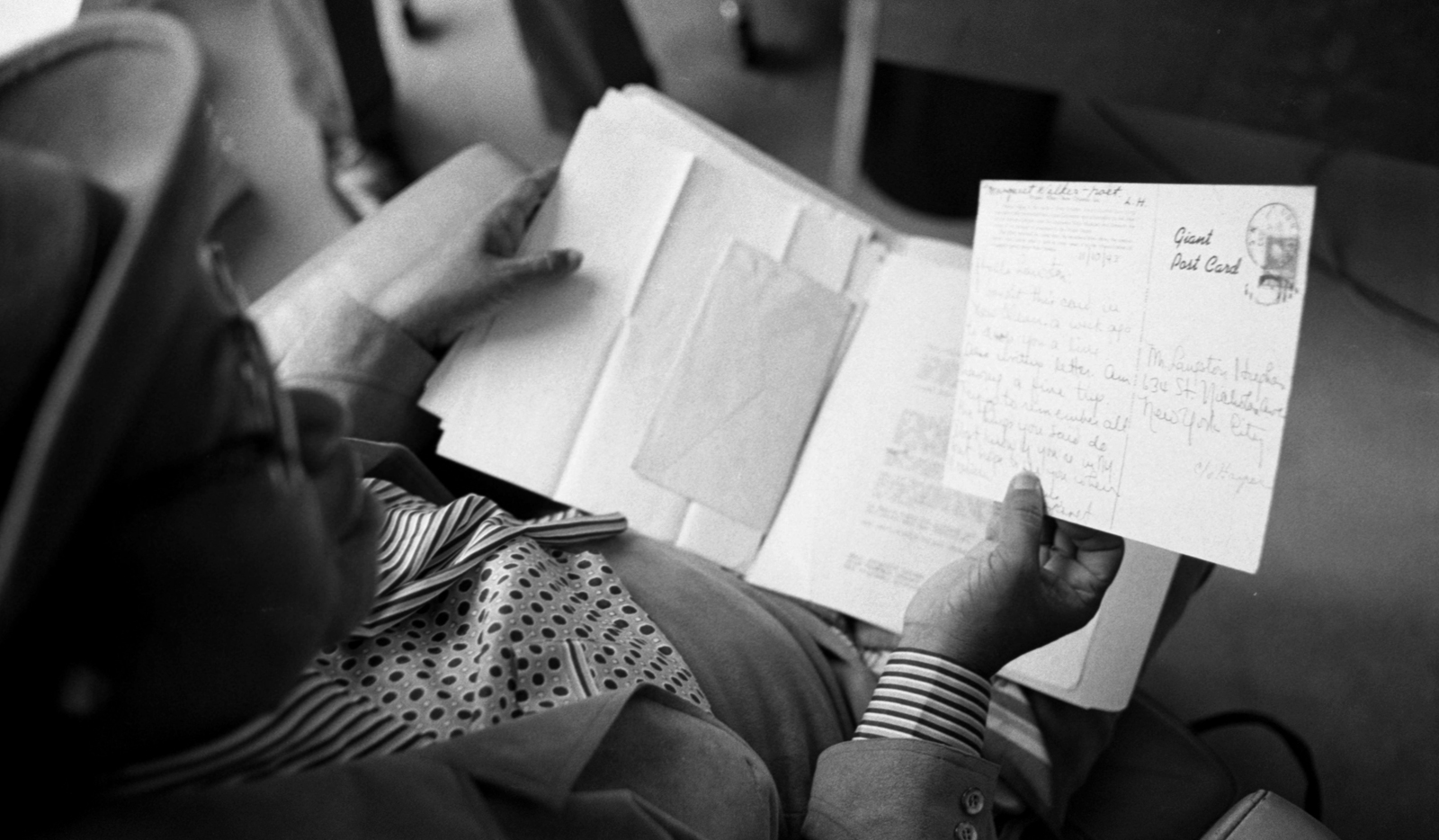

Our friendship dated from that first night in February 1936 until the day he died in May, 1967. I saw him last in New York in 1966 in October and remember until now his big bear hug at that meeting. Through the years I had seen Langston in sundry places. In Texas. In Boston or in Cambridge. High Point, North Carolina. Jackson, Mississippi. As well as in New York and Chicago. We spent six weeks one summer in a group of writers at Yaddo [an artists’ community in Saratoga Springs, New York]. But almost as wonderful were the cards and letters that came from all over the world: Carmel, California, the War in Spain, Mexico, London, and Nigeria. Almost everywhere he went, he wrote cards and letters and sent me his books for Christmas presents. I think I have about sixteen autographed copies of Langston’s books.

I saw him in the apartment he shared with Toy and Emerson Harper [close family friends], first on St. Nicholas Place and again in the house on East 127th Street. He visited us in New Orleans, took me out to lunch in Chicago at the Grand Hotel where I used to live, and came to dinner in Chicago and at Bedford Street in the Village. When both [my books] For My People and Jubilee were announced, he wrote glowing letters of commendation and congratulations. When Wright died in Paris, Langston wrote me a note on his Christmas card, describing his last visit to him: “Imagine my surprise to get to London and see in the papers that he was dead.”

He was a complex, sophisticated, cosmopolitan man, the humanist par excellence and always in love with life and people.

As I look back over those years, I remember Langston with genuine affection, and during these years since his passing, not only miss him but feel an acute sense of loss of his wonderful friendship. His easy carefree manner and even disposition belied his discipline and serious dedication to the art of writing and the theater. He claimed that he belonged to the cult of the simple and that he was like Jesse B. Semple [also known as “Simple,” a fictional Harlem Renaissance man Hughes created for his column in the Chicago Defender], but that was not entirely so. Jesse B. Semple gives you just a little bit of Langston Hughes. He was a complex, sophisticated, cosmopolitan man, the humanist par excellence and always in love with life and people. Of all the Renaissance writers, Langston seems to me to be the paragon and paramount. Next to W.E.B. DuBois, he has left the largest literary legacy. In his poetry he made an unusual contribution to the blues idiom and the jazz rhythms. In Jesse B. Semple he has created an unforgettable folk character whom we all love, and to whom we feel closely related. Langston loved Harlem, and he has immortalized the street culture of that community as no one else has.

I believe most of the Renaissance poets considered Langston their leader and their catalytic agent. Certainly Arna Bontemps did. I sometimes think that as fine a poet and novelist as Arna Bontemps was, he stood in Langston’s shadow for most of his career. But I know they genuinely loved each other, and there was never any jealousy between them. They collaborated on many books, and Arna knew how fond they were of each other.

Whenever I think of Langston now I see a great collage and montage of all the places we were together and all the books he wrote and his reading poetry in so many different places, or sending flowers when my first child was born, or playing a game of poker at a party and keeping an absolutely poker face, or walking back to Yaddo from the town of Saratoga Springs; a night in Orange, Texas, spilling a drink on my dress or saying you look like something straight out of Vogue magazine, and then seeing my little son barefoot on the floor in High Point [North Carolina] and red pot-bellied stove nearby, or writing to me when I went out to Iowa—”Don’t get too many degrees, or you’ll be smarter than I am,” pulling my leg you see. I heard his death announced on the radio and the shock stunned me so I could not bear to talk about it. How would it be to come to New York and not see Langston? Perhaps what he said on an autographed picture he gave me once is also my fitting epitaph for him: “To Margaret, who is such fun to be with.” I would like to say for Langston, who was always such great fun, that all of us who knew him best miss him very much.

One night in 1939 or early in the 1940s, Langston treated me to a ride on top of a double-decker Manhattan bus up Fifth Avenue from the Village to 150th Street. After the ride, which I found quite exciting, because Langston pointed out all the sights and landmarks, we went to the opening of a new bar called Fat Man. I like to think that that was one of the nights when Jesse B. Semple was born. The place was crowded, and we could scarcely elbow our way through the throng of black people celebrating the opening of a new black business in Harlem. Everybody seemed to know Langston, and he was laughing, smiling, cracking jokes as usual, and he was slapping the shoulder, shaking hands, and being greeted in turn.

Langston considered Harlem his home for forty-five years. He first went to New York when he was still a teenager to study at Columbia University. He quit or failed or ran out of money or all three—I’m not sure which—because his father stopped sending money, and then he went to sea. He sailed around the world, but particularly he went adventuring to the West Coast of Africa, and to the streets of Paris, where he had a doorman’s job in a night club for awhile, and where he met Bricktop [Ada “Bricktop” Smith, an American singer and performer who owned the Chez Bricktop in Paris], and where he was also once a beachcomber.

In his early twenties, however, he returned to Harlem, and there in the middle and late 1920s he became the accepted leader of the new Black literary school of literature, the Harlem Renaissance. I prefer to limit the Renaissance to the decade of the ’20s. We need to remember the two decades preceding the ’20s as the flowering of Afro-American culture leading up to the Renaissance. [By the turn of the century and soon thereafter] we’ve seen the published works of James Weldon Johnson and of Claude Mackay [a Jamaican by birth whose Songs of Jamaica appeared in 1912], even Francis Ellis Watkins Harper, who is the author of the first novel [Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted] by a black woman. [And other artists also are the] immediate precursors of the Renaissance, actually a bridge between the turn of the century and the ’20s. Many mark the beginning of the Renaissance with Claude Mackay and others with James Weldon Johnson.

I consider Langston perhaps the greatest success story in the Renaissance, and I think it is because of his special literary contributions in poetry, prose, and drama. Langston was unique, and all his work is touched with the magic of his personality: his ingenious manner of expressing himself, his genial disposition, his serious discipline, his dedication, and his remarkable versatility. Arna Bon-temps told me just before he died that Langston had left us this legacy of eighty-six published works, and in addition that he left 200 pages of a third volume of his autobiography in manuscript and such a voluminous set of papers that two years of work by his devoted friend and executor weren’t sufficient time to collate and organize all those papers.

Langston’s use of jazz rhythms and blues was the first black idiom in poetry since Paul Lawrence Dunbar [the first African American poet to gain widespread recognition in African American and white circles]. James Weldon Johnson’s black preacher in God’s Trombones came later, at least it was published later. Because Langston’s The Weary Blues came out in ’26 and James Weldon Johnston’s God’s Trombones in ’27, they must have been working about the same time.

I also regard Langston as a master craftsman in prose-fiction, whether in the short story or his longer fiction. This can best be illustrated in the five books of Simple tales [of Jesse B. Semple] largely collected from the columns which first appeared in the Defender. Many of us read Semple first in those columns, and they were always delightful. You could almost see Langston’s tongue in his cheek or hear him laughing. I see him pulling a leg in those stories. I still do. There are some very important facts of craft and art in those tales, which I daresay have never been fully explored, discussed, or expounded.

There is a use of folk material to accomplish several different tasks. To delineate character, to deal with racial issues, to combine human and pathos in book philosophy, and thus comment critically on life and contemporary society. From the section on Congress passing laws, Semple said that one thing he wished that Congress would do would be to set up game preserves for negroes down South, the way you had preserves for animals; you know, you don’t let people kill deer just indiscriminately, but you can lynch black people in Mississippi anytime you get ready. He said, now why don’t they just set up some preserves? With signs that say “Posted,” and you can’t kill negroes.

At midnight Langston went home and sat down at his typewriter to write. Between four and five o’clock in the morning, he went to bed, hence his rising at noon, and that was the way his day went. He rarely revised his poems; all his prose, however, was painstakingly written and carefully revised. He was methodical, organized, and always a serious writer. For many years and until quite recently, he was the only black writer living who made his living solely from his writing.

Langston wrote across forty-odd years. I say that his writing changed with each decade: that in the ’30s he was the writer of social protest; in the ’40s, the war was the eminent thing; and in the Cold War of the ’50s it was different; that in the ’60s he joined the revolutionary black writers.

[Zora] didn’t take cover because she was a woman, she put up her dukes and stood her ground with the best of them.

Langston and Arna both talked about Zora Neale Hurston disgracefully. She and Langston had a feud, a real falling out of friendship after an ill-fated collaboration. I think it’s very interesting to read her side of the story, and Langston’s side, and then to read what her biographer has to say, because the three give a fairly rounded picture of that big fracas.

Zora Neale Hurston is a bright and colorful figure of the Harlem Renaissance, and no one should forget it. There were at least a baker’s dozen of these women in the Renaissance, overlapping in the ’20s, some younger, some older. None of the men could eclipse Zora Neale Hurston, even though they tried. She was a natural born storyteller. She has written enough books to meet the taste or acceptance of anyone or everyone. Zora could not tell a poor story nor write a bad book. Jonah’s Gourd Vine, her first book, based almost entirely on folklore, may not measure up to the excellent novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, but it is a book well worth reading, as so are her other books: Mules and Men; Moses, Man of the Mountain; Tell My Horse; Seraph on the Suwanee; Dust Tracks on a Road. Most of these are not novels, but they read as smoothly as if they were.

She is a gal after my own heart. Arna told me once that I reminded them of Zora, and then when I bristled and got my hackles up, remembering how they talked about her, he backed off by saying she was exuberant and brilliant. But I know he was also saying she was contentious and extremely ambitious. I don’t think he intended to include me in her reputation for vulgarity. I don’t see how he could have. But I’m sure Zora and I have much in common: for unwittingly getting into scrapes and controversial issues. She didn’t take cover because she was a woman, she put up her dukes and stood her ground with the best of them.

Because she was a woman, black, and poor, it was impossible for her to take her Ph.D. in anthropology at Columbia in the 1920s. She came up from Florida, and she went to school for a while both at Morgan and at Howard. And then she went to New York, just as all the rest of them did, seeking her literary fortune, and she really hoped to get her degrees at Columbia. If Columbia was bad in the ’60s, when it had to be completely revolutionized, imagine what it was like in the ’20s. It was impossible. Even though she was an excellent student, there was no hope for Zora.

Everything has been changing this whole century, and one of the things that has changed most has been marriage and the family and the home, women and men.

Her marriage lasted very briefly, and I’ve been married thirty-five years to the same man. Everything has been changing this whole century, and one of the things that has changed most has been marriage and the family and the home, women and men. I have been a very lucky person in my marriage. My husband has always shied away from the world that was most familiar to me, but he always was a complete partner sharing in that home.

Zora must have died a frustrated woman, and there again we are not similar. She was accused of sodomy with a child. She died a pauper, after having worked as a domestic for a pittance, but she remains one of the brightest stars in the Renaissance.

Sleep well, Zora. We love you.

Carl Van Vechten [writer, photographer, Langston Hughes’s patron and friend] is not nearly as important an influence on the Harlem Renaissance as one has been lead to believe. His Nigger Heaven comes in that period, and what he’s saying is that Harlem is Nigger Heaven—that there was a period of prosperity in America, and everyone was on a hayride. And after World War I, America was making all kinds of money. You had these famous parties that began on Park Avenue and ended in Florida, and black people were the entertainers. They played the music, they sang the blues, and they read poetry at these parties. From the white critics’ point of view, this was an example of the exotic, unusual, primitive, child-like black person.

Nigger Heaven becomes very minor in the picture. He was a wonderful person in that he was like all the other white angels. There was no such thing as a person getting published without some assistance from somewhitebody, and that continued right straight through the ’40s and into the ’50s.

Almost as wonderful were the cards and letters that came from all over the world: Carmel, California, the War in Spain, Mexico, London, and Nigeria. Almost everywhere [Langston Hughes] went, he wrote cards and letters and sent me his books for Christmas presents.

I knew Carl Van Vechten, and today I will look at the portfolio of pictures that he made of me in the ’40s. I never was invited to those famous parties that he and his wife had—but they did invite me to their apartment—and I remember that I had my hair in an upsweep. I didn’t have much hair, and he said, “Do you always wear your hair that short?”

I said, “Yes, I was born with it that short.” Didn’t have any more hair than that.

What the Black writer was saying—and Langston says it better in that essay that first appeared on the racial malady [“The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” in The Nation, 1926]—is that we Black writers are going to express ourselves as we feel we want to express ourselves. And if white people like us, that’s fine, and if they don’t like us, that’s fine. And if black people like us, it’s fine, and if they don’t like us, it’s fine. We’re going to do what we want to do. When company comes, you send me to the kitchen, but I eat and grow fat. And I’m beautiful and strong. And one day you’ll see how beautiful I am, and you won’t send me to the kitchen anymore.

Wright—boy, you should have heard Richard Wright. He said everything he could against Langston. Wright said, now why do we have to beg the question of our humanity to anybody? We look in the mirror every day, we see what color we are, and we know we’re not dogs. So we don’t have to go along with that Shakespearean business, “If you prick me, do I not bleed?”

If you look at Wright, or if you look at me, we are not begging the question of Black humanity. We accept it.

We black writers are going to express ourselves as we feel we want to express ourselves.

The image of the Black woman in American Literature has been such a negative, derogatory image. That Black woman was always seen either as the beast of burden, the menial, the domestic, the buffoon and the clown, or the sex object, the amoral prostitute, Scarlet Sister, Mary, or Mamba’s daughters and Mamba, or you had no humanity whatsoever. Or you have the Black woman bearing the burden of color, the business of whether she was black, or whether she looked black or whether she looked white. And her role in literature was the same as her role in life, in society. There was no job too low for her to do, whether it was work in the field or work on the railroad or as the domestic servant. She would carry the clothes on her head. And then, what did we do? We built up that matriarchal myth—”she’s so strong, she’s the matriarch of the race.” We did away completely with the Black male as a strong figure by building up a myth of strong Black women.

We are coming up against two things in the American novel, the traditions of the sentimental and the gothic. Zora Neale Hurston’s Jonah’s Gourd Vine and Their Eyes Were Watching God follow a folk pattern and a sentimental tradition. Modern Black women novelists, like Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, are marvelous writers of the gothic. Toni Morrison is much better in The Bluest Eye and Sula than in the book that won [the National Book Circle Award], The Song of Solomon. What she’s doing with those Black women is a very strong treatment to exorcise that demon, and she does it in Sula, even more so than in The Bluest Eye.

She’s a marvelous craftswoman, and so is Alice. Toni is older than Alice—Alice is around my children’s age—but I don’t think there’s a lot of difference between Toni and me. She understood that the welter of folk material in the Black race is inexhaustible, that you can’t ever get through with that, that you can’t ever deal with all the strains of folk materials.

Nobody treats me finer these days than the people in Mississippi—all over the state. You should look at the statistics: people are coming back South.

I can take the heat; I can’t take the cold.

It’s late in the day for me. It’s not morning; it’s not noon. It doesn’t seem to be just early afternoon. I’m looking at a setting sun. And all of the things inside of me, I would hate to die with them inside of me. I want to get them down. I always meant to be a writer, ended up not much of a writer, because I should have done a dozen books by now. I have down almost 200 pages of autobiography, 100 pages of one novel, blocked out another novel, and have ideas for more. It takes a lot of energy to write, and you have to have more than physical energy; you need psychic energy.

I’ve got to get this stuff finished before the parade passes by.

William R. Ferris is the Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History, Senior Associate Director of the Center for the Study of the American South, and Adjunct Professor of Folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, he has made numerous documentary films and has authored over 100 publications in the fields of folklore, history, literature, and photography. His interviews with Delta blues greats, Give My Poor Heart Ease (2009) and his photography, including The South In Color (2016), are available from UNC Press.

This essay is edited from transcripts housed in the William R. Ferris Collection in Wilson Library’s Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.