In the summer of 2015, we filmed a short interview with Dorothy Allison, discussing the idea of southern mothers in conjunction with Keira V. Williams’s essay, “‘Between Creation and Devouring’: Southern Women Writers and the Politics of Motherhood.” Today, in collaboration with our 21c Fiction Issue, we bring you excerpts of our conversation. “Life constructs or mitigates your attempts to be ‘the perfect mother,’” Allison says. “But I never believed in the perfect mother.”

I wonder what the ideal Southern mother is. The one that cooks, caters. I’ve heard of those moms, I didn’t have one. But that’s very class-based.

I’m afraid I do have a rather complicated critique of motherhood that’s been altered and shaped by my life. I’m the weirdest kind of Baptist. I was raised a Baptist, and I tell people I’m a Zen Baptist, because I drifted quite seriously. And everything, it seems to me, is about class–everything. That concept of “southern motherhood,” I keep thinking of those Mary Cassatt paintings, when you talk about it, and I think that’s in many ways an admirable ideal, but it’s completely unrealistic. And I grew up in a family in which I do believe that my mother and my aunts particularly were, in some ways, I think, a paradigm of the working class mother—which means, exhausted, overwhelmed, terrified—with all the good intentions in the world, but just completely fucked up. [Laughs]

Life constructs, or mitigates, your attempts to be the perfect mother.

The odd thing is, is as soon as you say “ideal motherhood,” the connection in my brain is lesbian motherhood, because most of the lesbian mothers I have known, including myself, really—you know, even when we didn’t actually believe in the concept—were attempting to be ideal mothers. We couldn’t help ourselves. Because, in fact I know what I always thought is, if I screw up [at being a mother], nobody else will be able to have children. I can’t ruin it for the side, I can’t fuck up for all those other baby lesbians who want to make babies. So, I’ve gotta do a good job. I used to look at my kid and think, I can’t screw him up because he will be the evidence that we can’t really do this, which is, of course, absurd, because you can only hold those thoughts in mind, I think, for about 80 seconds, and then life intrudes. The kids start screaming, the cat knocks over a glass, the world goes on, you have to get a job, you have to go to Williamsburg and do a gig, and life constructs, or mitigates, your attempts to be the perfect mother.

But I never believed in the perfect mother. I never planned to be a mother. I found out I was sterile in my early 20s [small laugh] in brutal circumstances, with a doctor who said, “How long have you had syphilis?” and I’m like, “I have syphilis?” And he says, “Well, you have all the scarring of either syphilis or gonorrhea,” and I actually don’t even . . . It was so shocking that I stopped being able to think for a little while, and he says, “You’ll never have children.” And I’m like, I didn’t want kids anyway, but that’s kind of horrible. And I knew. I knew where I’d gotten the disease, and I knew . . . I was angry. Extraordinarily angry. Not just angry at my stepfather, who raped me and gave me the illness that had made this happen, but at the doctor, at the world, at Christ, at the Baptist Church. [Laughs] And at my mother. In between being, “Well, that means that I’ll never have to worry about getting pregnant”—not that I was actually dating boys anyway, but that can happen [sighs]—I had to look at the world differently. But mostly I looked at it through anger, and that meant that any mention of being a mom, or having children really triggered a lot of anger in me. And then [laughs] life makes corrections. I met a woman. I don’t believe in true love, I don’t believe in marriage. I’m an old-school radical feminist. I believe that the nuclear family is a nucleus of horror, and we should not recreate it in any form or fashion. But I’m a romantic, and I fall in love, and I fell in love. And when I’d been with Alix [Layman] for a few years, she told me she wanted children, and I said, “Well, we’ll have to find another woman for you to do that with.” That was my initial response. And about four years in, she brought it up again, and I said, “Let me think about it.” And I took a year to think about it, because I had to get over being angry. Because if we were going to make a baby, she’d have to bake the baby. And I was angry at her. I couldn’t even say, “I’m angry at you because you can be a mother and I can’t,” because also there was this voice in the back of my head that says, “You don’t want to be a mother, you want to make novels! You want to make revolution! There’s no time for making babies!” But it gets very complicated, and eventually I thought, I can’t take that away from her because it’s been taken away from me.

I met a woman. I don’t believe in true love, I don’t believe in marriage. I’m an old-school radical feminist. I believe that the nuclear family is a nucleus of horror, and we should not recreate it in any form or fashion.

So I played—I said, “All right, I’m willing to do this,” but in the back of my mind, I thought, “We’ll get her pregnant, she’ll make a baby, if I don’t like it, I’ll walk.” This is the ruthlessness of my life, or maybe just the ruthlessness of me and how I was raised, and that my survival instinct is very cold. But then we made the baby. And it was a difficult birth, and we had to have an emergency caesarean, and they pulled him out, wrestled him out. He was GIANT! He was 10 lbs, 4 oz. They pulled this giant child out of my lover and handed him to me, and he was in this gluey ball. I don’t know if you’ve ever—pregnancy is ugly. Childbirth is ugly. The baby, when you have a caesarean, comes out like a giant egg, but then it opens up, and the little arms and legs open up and the head comes back, and it’s a baby. And he opened his eyes. Two things: He was a boy. We’d pretty much known that, since when they pointed out his dick on the little, well, you know. [Laughs] The sonogram. “Oh, he has a large dick! He’s a boy? Oh, fuck! We’re going to raise a boy!”

I fell in love with him and I wanted to be the best mother in the world . . . But it’s enormously complicated to be a modern mother.

But he looked at me. And I know that babies can’t see. I know this, I’m not a damn fool, I read books. But he looked at me, and I looked at him, and I thought, “Oh, damn. I am going to go down the rabbit hole. The same rabbit hole my mother went down, my aunts went down, my cousins went down. This is bad.” But I couldn’t stop it. And the rabbit hole is, I fell in love with him and I wanted to be the best mother in the world and set about trying. But it’s enormously complicated to be a modern mother—I am not my mama, I’m not an old-school Baptist, I’m not . . . [sighs] I have a lot of counter-programming to all of those assumptions about what a mother should be. And one, I don’t want to raise a crippled child, and I will tell you frankly, I think most of the men of my family were raised crippled. Because they were doted on and raised without—they were never expected to be fully adult, so they grew up to be boys. I didn’t want to do to that to my—to our son. I wanted to raise a sane, compassionate male being.

Listen to all that awkward language. All that awkward language is about all of my resistance to the traditional definition of southern motherhood. I didn’t want to raise a cripple. But it gets deeply complicated, because there will be—I mean, I wanted to cook, and nest, I wanted to nest like a vengeance, and, boy, I turned out to have enormous familial talent for nesting. We’re also a butch–femme couple, no way around it, that’s just how it is, and I was Mommy. In fact, when we—for the first year, couple years, of his life, I was Mom—Mama—and Alix was Mom—Mother. And there was a differentiation. But actually she was Daddy. Let’s be clear . . . [Laughs] That’s pretty much what happened. But that whole paradigm of “How do you mother?”—you know, I can write a novel in which mothers are ruthless, and push, and shape their children, but in life, I am my mama’s girl, and I am—I probably did him just as much damage as all the mothers in my family because I loved him so much and I’ve raised a pig. My son doesn’t pick up behind himself. And that’s one of the byproducts of southern motherhood. It’s not a good thing we do [laughing], but it seems—that’s the place where I really fell down as an ideal mother. But he’s an independent cuss, and he has a sense of himself, and he’s becoming a grown-up. Boys take longer. Girls, even at this day and age, girls grow up faster and more sharp, and my son is—for awhile I thought he was soft at the center. Do you know what I mean by that? Not ever going to be fully able to care for himself. But, I have seen, he has a core of strength. And I think in some ways we helped him develop that. But the whole notion that mamas make children, that mamas make their babies into who they’re going to be, is absolute bullshit. They are who they are. He was who he was from the moment he did open his eyes and look around. All the ways that we tried to push him in some directions—that boy has a will of iron, he will be who he’s going to be, so that whole concept of making the child is ridiculous. You can fuck him up, I do know that. And I am responsible for the fact that he’s going to have to get a good job and hire a maid and pay somebody to clean his house, because he does not appear to be capable of picking up all the hair that falls out of his beard. My son looks like a six-foot-one rabbi. It’s just the most remarkable thing. Hair everywhere, beard. That’s his idea of macho.

What we did—Alix and I, in trying to be good mothers—that whole concept of being a lesbian mother in modern culture is really a challenge. I don’t know if you’re aware of it, but there’s a huge mythology in the lesbian community about lesbian motherhood. I mean, there must be a great many different models, and I’m sure some of it is regional. I know some of it is religion-based. And some of it is feminist resistance–based. Our model—for one thing, Alix was not a traditional feminist, and I was a radical lesbian feminist, and she was in the army, for God’s sake. That was one of our biggest differences. I’m anti-war, and she was a soldier. Oh well. Our concept of how we would raise children wasn’t the same. And she’s California, West Coast, and I’m hot-biscuits-and-gravy South. It’s—it didn’t mesh easily, but what we found was that in trying to be really good mothers, we didn’t do that bad.

Although, I don’t know what it looks like from the outside all the time, and that’s one of the big scary things. It’s not so much that—oh, I don’t know [chuckles]—George Bush is going to look at us and judge us as mothers; it’s what other lesbians will say about us as mothers that’s a big issue. And who those lesbians are. There are some lesbians we care what they think and there are other lesbians, like, “Eat dirt, bitch, we’re doing this.” There’s a lot of “Eat dirt, bitch, we’re doing this” in our concept of motherhood. It is never comfortable, and you never know what you have done that works and what you’ve done that doesn’t. There was so much violence in my childhood, I had a horror of perpetuating any of that, so one of the things that we agreed on even when Wolf was a tiny baby, was, he will not be spanked. There will be no corporal punishment in our family, there will be no violence, there will be no verbal violence, no yelling, so that we constructed a childhood for Wolf that was not anything like my childhood or Alix’s childhood. She was raised by an alcoholic, abusive mother. So we have all that stuff, but it’s sneaky.

But I understood immediately that it’s day-by-day. It’s not that you decide that you’re going to give it up and just be a bad mother, to hell with it. It’s that life wears you down and things happen and you’re surprised and you do stuff you didn’t know you want[ed] to do or know you would do.

When Wolf was about three years old, we moved . . . and the road we were living on is a country road where a lot of trucks—it’s on a hill, and trucks zoom up and down in front of our house all the time. So the first thing we did was we put in a fence, so the kid doesn’t get crushed. And I was thinking Stephen King, you know, all those terrible [things]. And then one day, the gate was open. I was in the driveway, I look up, and Wolf is running into the road, and here comes a truck. And I went—I think I literally flew six feet through the air, caught him just at the edge of the driveway—and I mean caught him just so that I—I felt when the truck went by, the breeze went by, and I spun around, threw him over my arm, and wham!, hit him, screaming, “You never, NEVER, run into the road!” Well, this is a three-year-old who has never been struck. His immediate response, aside from horror and pain, was he was mad. And he jumped down, turned around, and, you know, was just glaring at me. And then he burst into tears, I burst into tears, and here comes Alix. She hasn’t seen any of it, she missed the whole drama except that we’re both standing in the driveway sobbing. And she comes running up and tries to find out what happened. I can’t tell her, I’m crying too hard, and Wolf is like, “Mama hit me!” You know, and so she picks him up, and she gradually gets the story, and Wolf is like, “Mama hit me, Mama hit me!” and I’m standing there, and she’s holding him and she looks at me and she looks at him and he’s at a loss, and she says, “When your mama was a little girl, somebody hit her a lot. That’s why she’s crying.” And Wolf reaches over and puts his hand on me. [Deep sigh] That’s the only time I’ve ever hit him. Part of what happened in that moment was that I understood some of what happened with my mother. My mother wasn’t violent. My mother, she slapped me once, and it wasn’t for something I’d done, it was for something I said. You know, wicked mouth. But I understood immediately that it’s day-by-day. It’s not that you decide that you’re going to give it up and just be a bad mother, to hell with it. It’s that life wears you down and things happen and you’re surprised and you do stuff you didn’t know you want[ed] to do or know you would do. And I’ve seen it with my sisters. All of us reacted against our childhoods by trying really hard to be good mothers. But my sisters were both single mothers, working. I had a partner. When Wolf was a year old and it got to be Mother’s Day, I sent both of my sisters flowers and chocolates and apologies, because I had always said nasty things about them, because they were terrible mothers. They were exhausted, overworked, struggling alone. They had no way—they couldn’t even access ideal motherhood. They were just single mothers. I understood that suddenly differently.

I think it’s a criminal thing we do to girls, creating this notion of the ideal mother.

And I have to say, every year of my son’s life, it has changed and been a different challenge. Every year there is yet some new and marvelous way I can fuck up, that I have to watch. But the biggest thing is to remember that he is his own person. I don’t get to decide who he is. [Laughs] He tried to join the army. I thought I would lose my mind. [Laughs] You know, I was watching boys go off to Iraq and Afghanistan and come home minus legs, and I’m like, “You know you’re not going into the army.” That was my first response, and he was eighteen. He took a bus to Sacramento, and tried to sign up, and I couldn’t do squat-one about it. And all of a sudden I had to be yet another version of the good mother. Take a deep breath. [Takes a breath] He’s his own person. And try to talk rationally to him about, “Okay, if you’re gonna do this, you’re going to go in from—” [Laughs] Trying to construct a way for him to do it that didn’t seem to be quite so dangerous.

It seems to me that, as an ideal mother, I am an absolute failure. But as a trying-all-the-time, Zen mother, I’m doing all right. Managing. But I think it’s a criminal thing we do to girls, creating this notion of the ideal mother. And we don’t help them with movies and books. There are good books that really are about the difficulties of raising children [today], because it’s a different time frame in 2015 than my mother faced when I was born in 1949. But [we still put these demands] entirely on girls. But children aren’t raised by just the mother. They’re raised in families, and, like I said, I do believe the nuclear family is a horror-show, and that the only thing that saves us is that feminism has made some really huge shifts in how families are organized. But in no way near enough. Let’s never lose track. [Laughs] It’s still the case that my sisters, with all the good intentions in the world and having married men they genuinely loved, wound up being single moms. That’s an outer circle of hell.

Perfect Mothers and Social Class

I think there are different versions [of the perfect mother]. I really love a lot of Midwestern literature, and there are some wonderful novels about motherhood that come out of the Midwest, which it seems to me [is] because they’re rural. And rural is in some ways equivalent to southern. At least in the construction of the family unit, and that, in fact, the raising of children falls almost entirely on the mothers. And the fathers are this dark shadow that comes in every once in a while and yells and then goes out again. That’s the bad version. The good version is, the dark shadow comes in, earns a living, provides some level of security, and, in good families, in good situations—which is a lot about money, and class—actually can provide a loving nucleus. I have friends who were raised in loving families. I always look at them with a kind of awe. I don’t genuinely understand that. I understand fucked up. I understand people so exhausted they’re driven to violence. And that, it seems to me, is one of the things I write about. It’s one of the things I try really, in a focused way, to do in Cavedweller because when I made Delia up—I mean, I write about women in trouble and I write about broken families, and Delia Byrd in Cavedweller loses her kids. And she loses them because, in fact, her husband is a violent abuser. And she runs to save her life, and his way of really sticking it to her is, he takes her girls. And because she has run, she loses them. So that, then, the book becomes, when she goes back and tries to get them, and the deal she has to cut to get them. Um, she has to put herself in his hands again and make a compromise to take care of him, because that’s what he mostly wants. But of course, by then, her girls are adolescents and they hate her. She’s trying to be the ideal mother. Of course, she also has this love child for whom she has also theoretically been an ideal mother, except she’s a complete failure at it, because she’s having a nervous breakdown and barely functioning. I wanted to put on the page what I thought is realistic about poor women and working class women who are trying their damndest in situations in which they have so little power, so little control, and nothing they do is right.

I wanted to put on the page what I thought is realistic about poor women and working class women who are trying their damndest in situations in which they have so little power, so little control, and nothing they do is right.

That’s what I think of as the paradigmatic situation for most women. At least, most working-class women. But actually, I’ve dated rich girls, and they’re pretty miserable too. They have some pretty screwed-up dynamics working. Different. They don’t have that—I remember my mother’s face when there was no food in the house. The horror of that’s the baseline of southern motherhood. You feed your kids. If you can’t feed your kids, you might as well die. I remember that look on my mother’s face, feeding us soda crackers and ketchup. That’s a real memory from my childhood. And she could put salt and pepper on it and mix in a little mustard and make it a meal and it wasn’t that bad, but her hate—her self-hatred and her horror of, in her mind, utterly failing to take care of us meant she didn’t notice all the other ways in which she was utterly unable to take care of us. This just sets up an impossible situation. But we don’t give any quarter to it. We don’t recognize the dynamics in which the women who fail at motherhood are trapped. The ways in which it’s a fait accompli, you can’t really escape it.

Especially trying to make a living, and working really terrible jobs, so that you do come home so exhausted you can’t see. I can remember, when I was going to college, my sisters had children, and were working and supporting their children, and at least one of them at that point was a single mom. And I remember coming home from college, which is—let me just say, the huge dislocation in the working-class family, the kid that goes off to college comes back a completely different person. I came back an arrogant bitch. An arrogant feminist bitch. And my attitude toward my sisters really held them accountable and responsible in ways that were just stupid. It was as if I were imposing on them the structure of a class that I didn’t belong to, except that I wanted so much to belong to it that I was committing what I think of as one of the great sins of my life. Holding them to a standard that was impossible. Not having any compassion for their situation. It’s taken me most of my life to earn their forgiveness. But some of it is [that] you just don’t see. We set up this concept of motherhood that is absolutely impossible. My sister June, whom I adore, has worked for twenty-five years wiring guidance systems for missiles. Do you know what that means? She works in a clean room. That means she goes in early every morning to get into a white suit, puts her hair up in this rigid thing, and goes into this sealed room—because, you know, wiring systems, guiding systems, it’s got to be clean. She works in there for eight hours every day, doing repetitive work that is mind-numbing. She took the job because her baby had been born with a severe birth defect, and she needed good health insurance and she needed an income. Twenty-five years of working that horrible job. I won’t even tell you all of the things that are involved, it’s just so horrible. But she has done it. That’s her concept of being a good mother. That means she comes home so deflated and exhausted, she’s barely functional. So that her relationship with her children is minimal, because she doesn’t have the energy to talk. But we never acknowledge that that’s a factor. There’s the television moms who, if they have jobs, have maids, or help, or the grandmother lives with them. Have you ever looked at the families on television? They do not reflect what I see happening to real mothers. North, South, East, West. But I do believe that in the South, our standard is so rigid, and so much tied into church and religion, that the sin of being a bad mother is unforgivable for us. No compassion. We’re all going to go to hell. [Laughs] And having earned it!

But my sisters have raised good kids. Screwed up completely, but not because they were bad, bad mothers. We raise some—we do terrible things to our children. To poor kids particularly. We create impossible situations for them. I think that’s my biggest—it’s a funny thing. I’m now an old feminist. I am keynote at an old lesbians conference, and we’re all old. So I look at my life as a radical feminist and the thing I find most horrifying is the lack of compassion that we have shown in our politics. The one thing I learned deeply from Grace Paley was that the core of politics is compassion, and that if you don’t have it, you’ve screwed up in unforgivable ways. And if you do have it? You can screw up and still [succeed], because to have behaved with compassion gives you a position from which you can reach people. So far, so good with my kid. Compassion helps.

Marriage Equality and the Nuclear Family

Like I said, I do not believe in marriage or monogamy. But, I’m married, which I find hysterical. My girlfriend fortunately also finds it semi-hysterical. In California, just before Proposition 8, a bunch of our friends were getting married. Gavin Newsom was letting people get married in San Francisco, and my friend Jewel, and Di, were planning their wedding, and they were like, “You wanna get married,?” and I’m like, “I don’t believe in marriage! Marriage is a con game, marriage is an unjust, illegal economic relationship in which women are property.” You know, the whole feminist critique, right? Okay. So, I’m not going to get married. But six days before the vote, which was going to be Prop 8—but we didn’t know Prop 8 was going to pass—Kate Kendall called me up and she said, “You’re married, right?” and I think, “No, I don’t believe in marriage.” And I gave my whole rap, and she’s like, “Wait, wait, wait. You can’t do this.” And I’m like, “What do you mean?” And she says, “You’re famous. You’ve got to get married.” And I’m like, “No, I don’t!” She says, “Yes, you do, we need you!” And it was like, “On the front lines, on the battle lines!” “Oh, fuck. Alix, we’ve got to get married.” And, to a certain extent, that was what happened. We said, “Okay, well, alright. We still don’t believe in it, but we’ll do it.”

The contradictions of being a responsible citizen and a feminist is just endless. It’s a good damn thing I’ve got a very, highly developed sense of humor.

And so we went and, the day before the vote on Halloween, we went out, [and] Jewel and Di got married. We piggy-backed on their wedding because I’m working-class and cheap and we didn’t have any money. They had a big fancy wedding, we came to their wedding, and we got married at their reception. And Jewel, in fact, married us, because Gavin Newsom legalized all the supervisors, and she was a library supervisor. So she married us. So then, we’re legally married. I’ve got a marriage certificate, I’m legal. Two days later, Prop 8 passes. Nobody else can get married. And suddenly, there are only 18,000 of us in California who are legally married queers. And suddenly, I have a responsibility in an institution I do not believe in. And since then, it’s gotten even more complicated. Because, in fact, part of what went along with this whole marriage thing is that we do have a child. And we have property. And we have family. And my family’s poor. And I was pretty damn clear, if anything happened to me, the locusts would descend. Now, I love my locusts. But they’re locusts. And I know that marriage protects Alix, and protects my son, from a rapacious family. And all the ways in which I love my rapacious family will not excuse the fact that they would show up and take everything they could, because they need it and they feel justified. But they always feel justified. We’re queers, our relationships aren’t real. They’re not recognized. And even if they love me, they would still show up. Marriage provided a degree of protection that we didn’t have before, and I had to recognize that. Even though I think it’s a crime. I still think it’s a crime. I actually believe in contract relationships. I also think they should be timelined, because, you know. You never know. And there are so many pretty women in the world.

But, here I am. And it’s a joke of God. I was one of the 18,000 legally married. I was deeply ashamed of this, on many levels. Which meant, of course, I had to organize for legalizing marriage, even though I believe marriage is an unjust institution. [Laughs] The contradictions of being a responsible citizen and a feminist is just endless. It’s a good damn thing I’ve got a very, highly developed sense of humor.

Fiction Changes the World

I don’t actually believe in God, unless I’m in a car wreck, and then it’s, “Jesus, save me.” Can’t get away from that Baptist upbringing. The car wreck that’s in Bastard out of Carolina—the whole of the first chapter of Bastard out of Carolina is all true stories. And it’s a game I play. I figured I would write this, and everybody who knew my family—everybody in my family would laugh, because they would know that it’s all true. With fictional glossing . . . Although, my sisters are still mad at me that I didn’t take them with me when I robbed the Woolworth’s. They never will believe me that I didn’t rob the Woolworth’s. I made it all up . . . But yeah. No, I was—my mother didn’t see me until she came out of the coma three days after I was born. You can do things in writing in which you can glorify what other people would hold in contempt, which is the wonders of language and fiction. You can make people feel and care about people that they have every reason to fear and despise.

Fiction both allows a kind of a distance, but at the same time a complete intimacy, because you inhabit people completely different from you. So you see them as human. And you see them as yourself.

I believe that fiction changes the world. And I think that fiction with a political movement is incredibly powerful, and I think it’s one of the reasons that the early women’s movement was so effective. Because there were great books. Some of them were not greatly written, but they were highly powerful and effective and emotionally laden. And some of them were really beautifully written. The women’s movement and the literature of the women’s movement really had an enormous impact. But we don’t really—we. We. The broad-based culture. [Sighs] We don’t think of ourselves as the actual individual human beings that we are, so that we don’t see people as real. I find it enormously exciting to watch young people. It’s like they’re suddenly waking up, lifting their heads, and saying, “Oh, policemen are killing young black men. Oh, my goodness, how long has this been going on?” Well, babies, READ NOVELS! We’ve been writing about it for a long time. And it is in novels where in some ways you can say, “Oh, but it’s fiction.” Fiction both allows a kind of a distance, but at the same time a complete intimacy, because you inhabit people completely different from you. So you see them as human. And you see them as yourself. That changes things.

Loose Leaf with Dorothy Allison

Dorothy Allison is the author of the award-winning Bastard Out of Carolina, Cavedweller, Two or Three Things I Know for Sure, Trash, and The Women Who Hate Me. She now lives in Northern California, but dreams in Carolina.

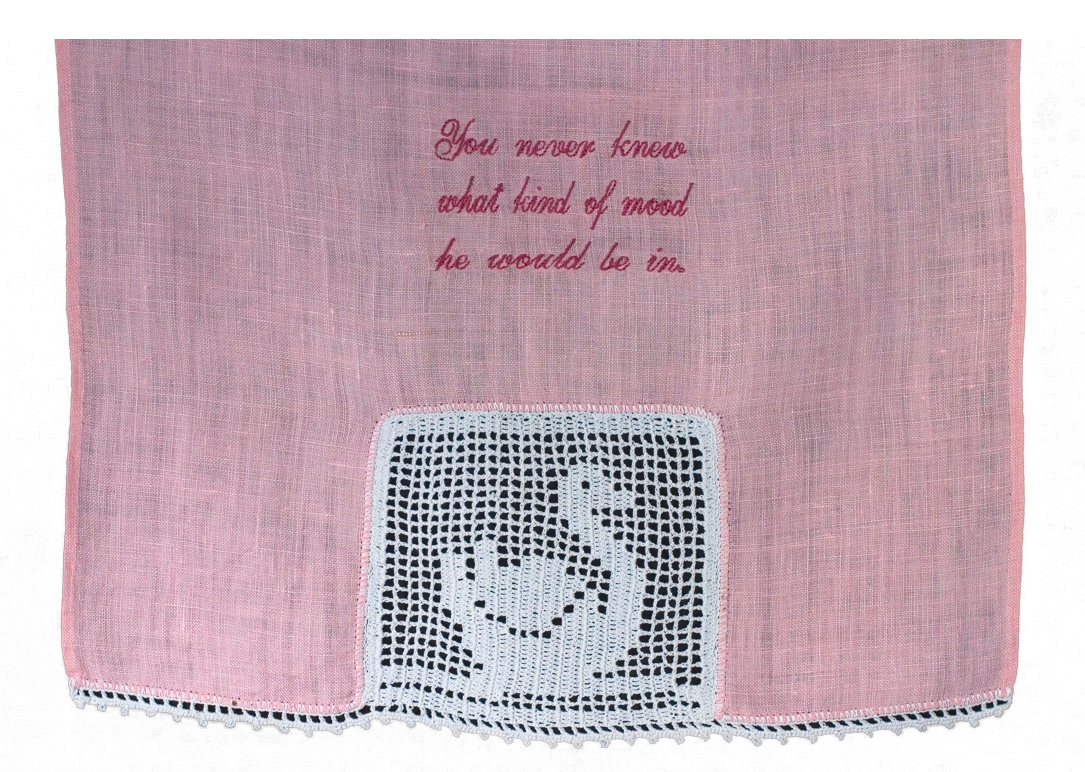

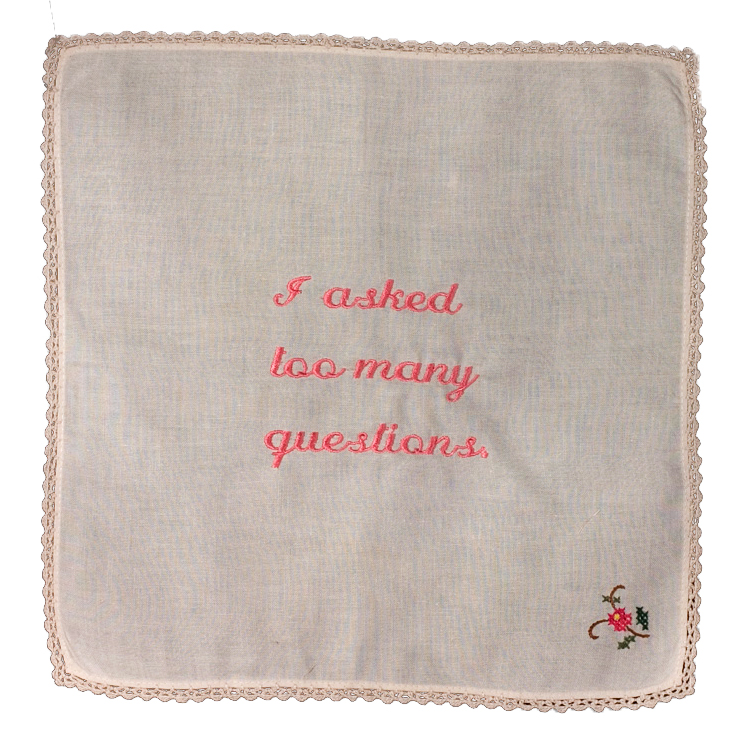

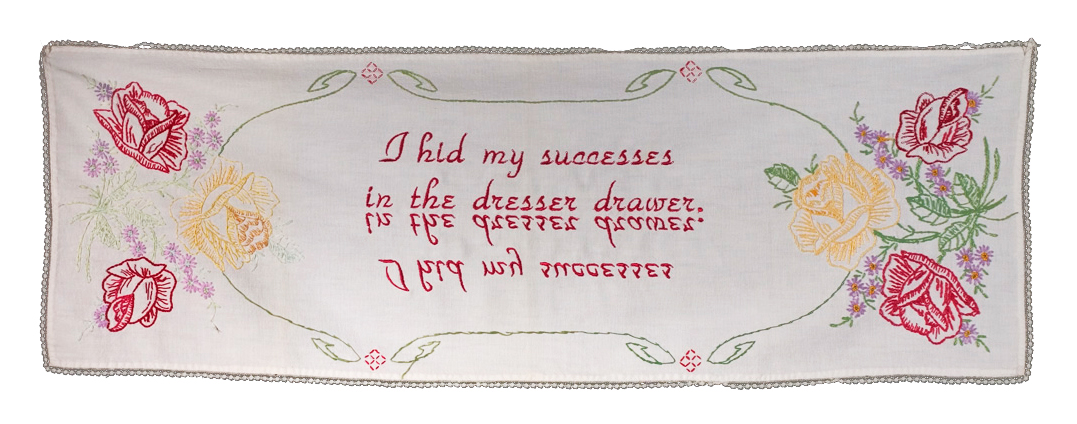

The work of conceptual artist Susan Harbage Page explores (im)migration, race, gender, and nation. Harbage Page has exhibited nationally and internationally at major museums and public institutions in Bulgaria, France, Italy, Germany, Israel, and China. Harbage Page is an assistant professor in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and she is a fellow at Carolina’s Institute for the Arts and Humanities. Learn more about her work here.