First things first: Representative Renitta Shannon, who represents Georgia’s 84th district in the state’s legislature, was raised a PK—a preacher’s kid. In her father’s Primitive Baptist church—one so doggedly literal that it frowned upon 11 a.m. Sunday communion because the practice debuted at the Last Supper, that world-changing evening meal—she absorbed and sometimes questioned the contradictory. White Jesus floating above Black parishioners. The faithful women of the flock barred from the pulpit. Her father, a conservative pastor who took his children to protest George W. Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” policy. The imperative and power of “testifying” in the Black evangelical lexicon: speaking one’s truth—even, and especially, painful, self-implicating truths—before an audience of witnesses.

So it may have been preordained that Shannon would not be silenced once she took office. She came out as the first bisexual lawmaker in the Georgia assembly. Known as a reproductive justice advocate before her election, she speaks publicly about having an abortion while a college student, counting the pennies she earned as a Cracker Barrel server to pay for the procedure.

In March 2019, Shannon took the podium at Atlanta’s gold-domed Capitol. And she refused to relinquish the floor during the House’s debate about HB 481. That Republican-backed measure drew national attention as part of a wave of state laws that attempted to ban abortion as early as six weeks into pregnancy—when most people aren’t yet aware they’ve conceived. (It remains legally blocked.) Shannon was physically removed from the dais by security for staging her one-woman filibuster in a state legislature that doesn’t allow that delaying tactic. She made the news and waves in her own party. But she’s not sorry. Here is an excerpt of our conversation, in which she talks about why she wouldn’t step down and why fellow Democrats need backbone and imagination.

This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Cynthia Greenlee: I gather you are, as some folks say, now “happily unchurched.”

Renitta Shannon: I would have a lot of conflicts where I would ask questions [about things] that just didn’t make any sense, looking at gender roles and white Christianity, which is essentially what it is even though this was an all-Black church, you know.

It is interesting because I am the first [known] bisexual person to be elected in Georgia. Well, my dad, before he passed away, was doing activism to say that all of these new churches that are starting to marry gay people, that’s not right. That was “straying” away from the Bible. But my dad was not a Bible thumper. He was one of those people that if you asked him for a solution to a problem, he would say, “In my opinion, I would pray.” But he wasn’t the kind of pastor that would get on a street corner with a megaphone, although his whole world revolved around religion.

CG: You talked about your abortion story several years ago. There’s video of you online talking about how you were at the University of Florida, making money to support yourself by waiting tables. And doing the math about how many shifts it would take to pay for your $500 procedure.

RS: I had an abortion in college, but because I’ve been always so independent, I paid for my own abortion. I didn’t discuss it with my family. Because the main thing you don’t do is be gay. That’s No. 1. Don’t do that. That’s worse than anything else. You could kill somebody, and I’ve literally seen acceptance for that. But you definitely cannot be gay. And then the second thing is, obviously, you can’t have an abortion.

My dad passed away. He never knew that I had an abortion, because I didn’t feel that that was anyone’s business. He certainly wasn’t alive to see me get elected or talk about my abortion story or being queer or anything like that.

CG: When did you first hear about HB 481, or that there would be something coming legislatively to ban abortion?

RS: In early 2019. At that point, I didn’t think we were going to see an abortion bill. A couple of months later, we start to hear rumblings the Republicans were going to pass a trigger bill [meaning] if Roe falls, which Trump is trying to make happen, then, boom, this would outlaw abortion immediately.

But at the same time, 481 was already in the legislature. It had already been filed and everybody—even Republicans who are secretly pro-choice—thinks [the bill to watch was] going to be the trigger bill. . . . Then, we started to hear [the gop wanted] to switch from the trigger bill to 481, [which meant] there was a whole lot of problems amongst Republicans. You approach some of the [moderates] in hiding, and they’d say they just hope that none of this comes to the floor so that they don’t have to vote on it. They were all like, No, no, no, no, no, don’t do the 481 [and] let’s just keep the trigger bill, because at least that one gives us the shield of “They’ve done it at the federal level.” It doesn’t get them in trouble. It’s easier for them to explain to their constituents, but 481 proactively pretty much outlaws abortion. They didn’t want any part of it.

But I don’t give them any credit. . . . I have no sympathy for anybody who says, “Well, I don’t really agree with this, but I’m going to vote for it because my party’s making me.” No, my party can’t make me vote for things. You’ve got the same freedom.

CG: So at what point did you decide to share your abortion story and stage an intervention?

RS: I was talking with [Republican] Sharon Cooper, who is the chair of the health and human services committee, which is where this bill went through. I was talking with her every week to get updates about, are they really going to put this one on the floor? At one point, she said, “I’m getting pressured to put this on the floor.” I said, “OK, what day is this going to be on the floor?”

Do you know about Crossover Day?

CG: No, I don’t. Tell me.

RS: So the Georgia Constitution says we’re in session for forty days. Crossover Day is the halfway point in session. [The] significance of Crossover Day, which is like day nineteen or day twenty, is, usually, if a bill has not passed either the House or the Senate by that point, it’s dead for the rest of the session. So, basically, we’re trying to run out the clock.

[The committee chairwoman] was superseded several times, literally, by men in the committee, the Republican leadership who were standing there saying, “Hurry up.” Like, they knew she was delaying. They were like, “No, you’re not going to let all these people speak.” Give everybody one minute to speak. And that’s it.

I had said to myself, “OK, I’m trying to work with these people with this bill to not let this shit come to the floor.” But if they put this bill on the floor, I had promised myself I would make Speaker [David Ralston] physically remove me because, coming from an activist background, I am no stranger to direct action. My plan was to go down there and speak so long that I would cause such a ruckus that the speaker basically would have to shut down the session for recess and hopefully [kill the bill]. Usually, they like to do the worst bills late at night and Crossover has to end by 12 a.m. . . . We get in there at 8 a.m., and we don’t leave until [midnight].

CG: So what are your Democratic colleagues doing?

RS: The Democrat caucus? They weren’t doing anything. They were like, “Yeah, we’re just going to vote. No, we’re in the minority. We can’t do anything. So yeah, we’re just going to vote.” That’s their plan for everything: Just to lose by voting. Never anything outside of the box. . . . I have done Fight for 15 rallies where we walk into McDonald’s and just start yelling “Fight for 15!” so everybody will understand that this is an issue. You cannot just look the other way on it.

[Then Shannon spoke to the house dean and said,] “I’m just telling you, if they put this bill on the floor, I’m going to act a fool. I’m just telling you.” I knew that if I was going to force the speaker to remove me, the dean would be the person who would come up and try to get me down. . . . So he said, “If they put this bill on the floor, that would be the worst thing I’ve seen in forty-five years.” In the end, he said, “Usually, I would tell you not to do something. But I think you should let it rip if they actually do that. . . .” I thought he was the only person I would have to worry about. [I knew] I’ll probably get in a lot of trouble, but at least [it was worth trying to stop] the abortion bill because they would have to work on it, come back, and try again next year.

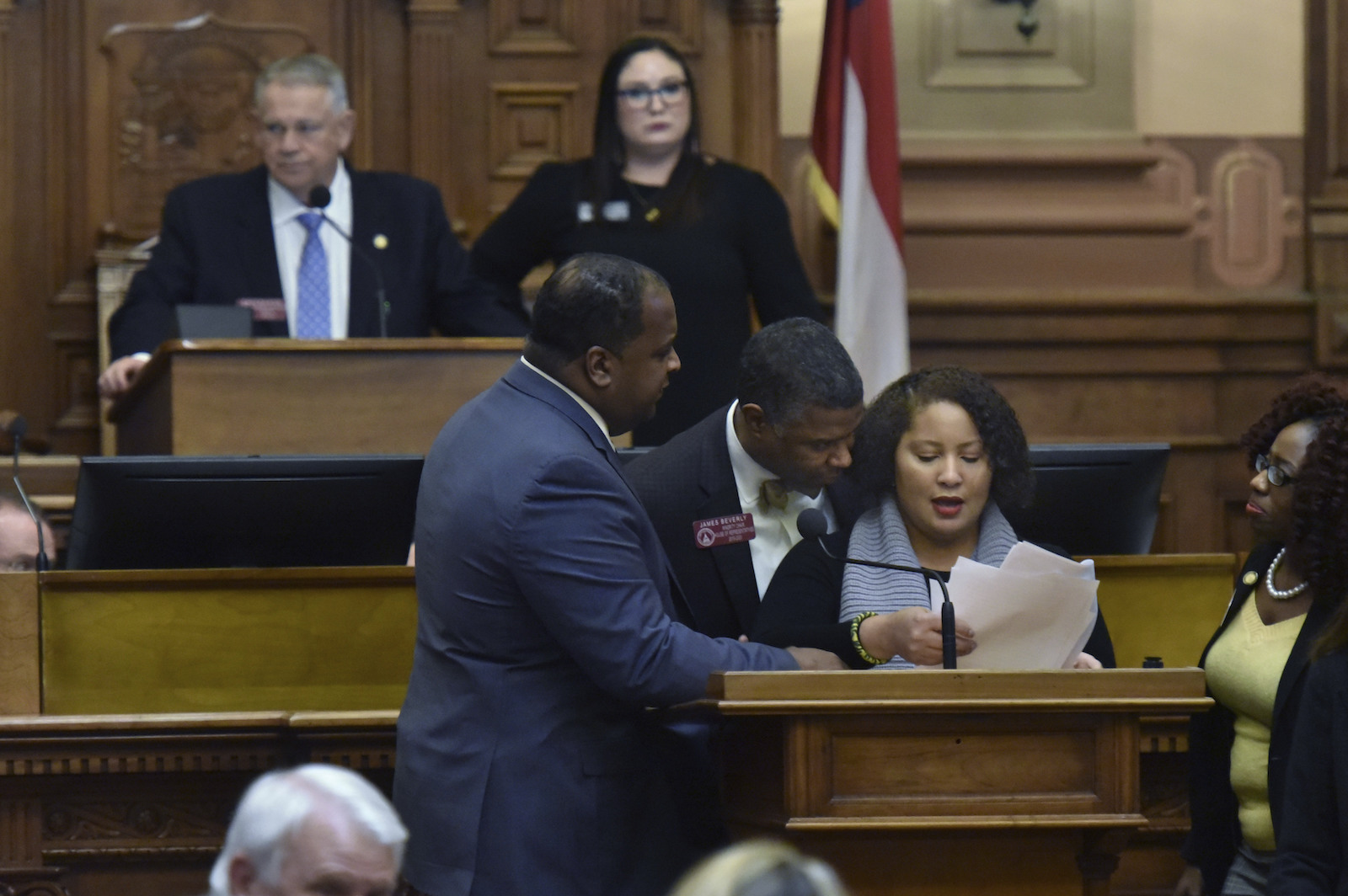

I printed off a bunch of stuff [to read], ready to talk. I was allotted ten minutes because, actually, I was a speaker for the caucus, which is called the “minority report.” The party in the minority gets to speak for twenty minutes total, but ten minutes to say why they disagree with the bill. Then I got to about twelve minutes, and the speaker said the lady needs to wrap up her speech. And I just kept talking over the speaker. So then about a minute later, the speaker cut my mic. OK.

Which is another interesting story about how they got the technology to cut mics. That also was a result of another Black woman refusing to stop singing a song—before I ever got there in the legislature. And I didn’t even know that, I guess it was like 2010 or something. There was a Black woman elected who went up and started singing an old Negro spiritual and [wouldn’t] stop. And so they installed something where the speaker could cut off the mic from where he is. So this is the second time Black women have said, “No, you’re not going to shut me up.” We’re at about thirteen minutes now and the speaker [is saying,] “The lady needs to leave the well.”

CG: So who are all the people who start coming to the podium? You can hear someone saying, “Back away.”

RS: The first person you see run up in the video is a young Black guy, who is the [minority whip] for Democrats. Every person you saw coming up to sit me down, not one of them is a Republican. Not one. Now, we’re friends, and he came up and he grabbed my wrist. You saw, he tried to take the papers away from me . . . like, “Come on, we need you. You don’t have to do this.” So I—kind of like how a parent would do through their teeth, like when you’re in a store [with a misbehaving child] and you’re not trying to make a big production—I said through my teeth, “Go and sit the fuck down.” Trying not to let the public see that I was telling him to get away from me. And that’s when he threw up his hands. So then you see a bunch of white men in the background riding around, trying to figure out what to do, because . . . they understand that this is not business as usual for me.

So then the speaker sends the tall Black man you see in the gray suit who’s standing next to me. That person is not a legislator, but the speaker’s bodyguard. I do believe they specifically sent a Black man because they knew it [would look] bad if a white officer came down there and tried to put his hands on me. What people couldn’t see in the video was he was using his body to edge me off the stage so he wouldn’t have to touch me. He was just using his body to push me further to the right, trying to kind of like bump me where you couldn’t see it so that I would get offstage. He kept turning around, looking to get direction from somebody, like, “What do I do?” Whatever. Because Georgia also has a law that legislators can’t be arrested during active session.

CG: But more people are there.

RS: There’s a crowd of people around me. They are all up there saying, “Baby, baby, don’t do this. You need to sit down.” Pretty much just the folks who are not interested in resisting in the caucus, they were coming up there to ask me to sit down. So at that point, I was really angry because not one Republican is up here asking me to sit down. But you got Democrats asking me to stop protecting women’s bodily autonomy. And why are Democrats coming up here to ask me to sit down? They should be joining me in saying we’re not going to leave!

What you hear in the video [urging them to leave her alone] is Park Cannon [another Black junior representative who’s also told her abortion story publicly] telling them to sit down. But she’s trying to not say it too loudly because she doesn’t want Republicans to understand fully that Democrats don’t support me doing this. She’s trying to tell them guys, “Back away from her. Leave her alone. She knows what she’s doing.”

Finally, the police officer next to me looks up to the police officers in the gallery, throws up his hands like, “I don’t know what else to do with her. I’m just going to have to grab her.” That’s when he grabbed me and pulled me offstage. The only reason that I went—because I was going to take it further than that—was because of the embarrassment [of the Democratic caucus appearing divided]. [If fellow Democrats] would not have come up, I feel that my plan would have worked. I do. I went back to my seat. All this happened about 10:30 at night. This took about twenty-seven minutes. The bill ended up passing with ninety-two votes. One Democrat voted for it.

CG: So I’m assuming it didn’t end with that. Were there repercussions for you? You referenced the fact you’d done the minority report representing the party a number of times. Did that continue?

RS: This session, this year, I’ve only gone to speak one time at the mic. But I’m not giving any minority speeches because giving the report requires the trust of the caucus and a lot of [the Democrats], the white members specifically, were very upset [and] were all going to the leader of the caucus saying, “I can’t believe you let her do this.” You know, like these men are able to control me? We’re all adults here. One even threatened to resign.

The caucus leadership call[ed] me in and asked me to make an apology to the caucus. I told him, I absolutely will not make an apology to the caucus because I don’t have anything to apologize for. . . . And then they said the caucus is really torn up and they said that they’re really scared of you. I said that what I think is very funny is [that] not one of these people has come to me directly, and they know where to find me. So why is that? If you’re afraid to talk to your colleague about how you feel about what I did, then how are you going to fight Republicans?

This interview first appeared in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Fall 2020).

Rep. Renitta Shannon (Democrat) represents Georgia’s 84th District. She is a reproductive justice advocate who has spoken about her personal abortion experience and sponsored bills on improving maternal health, among others. She is also a cofounder of Her Term, an initiative to elect progressive women in Georgia. Visit her website at www.renittashannon.com.

Cynthia R. Greenlee is a historian, writer, and editor at Colorlines. In 2020, she won a James Beard Foundation Award for food writing, and she’s coauthor of The Echoing Ida Collection, an anthology of Black writing about reproductive and social justice (forthcoming January 2021). Read more of her work at cynthiagreenlee.com.Header image: Thousands of protesters gathered at the Georgia State Capitol building to march in opposition to the HB481, May 25, 2019, Atlanta, Georgia. Photograph by Steve Eberhardt/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News.