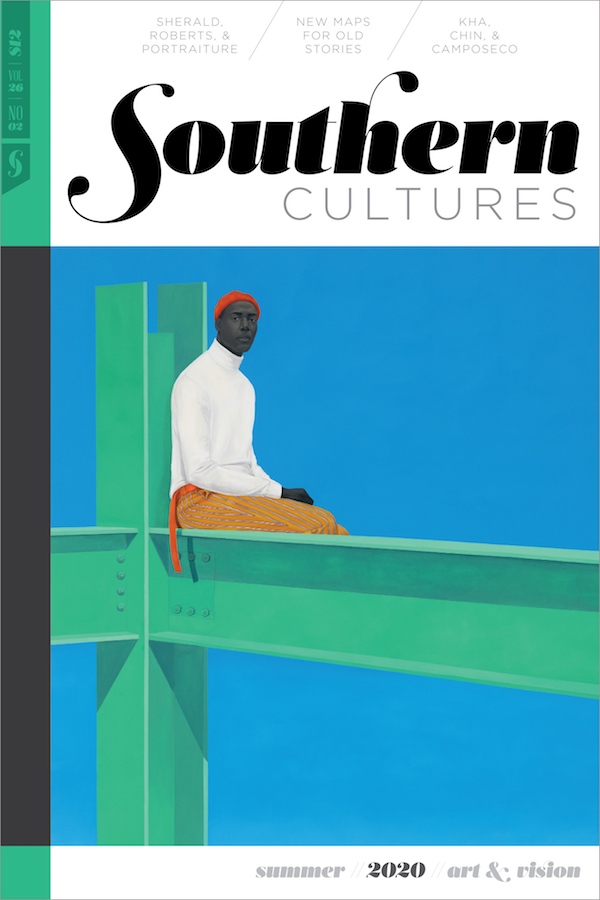

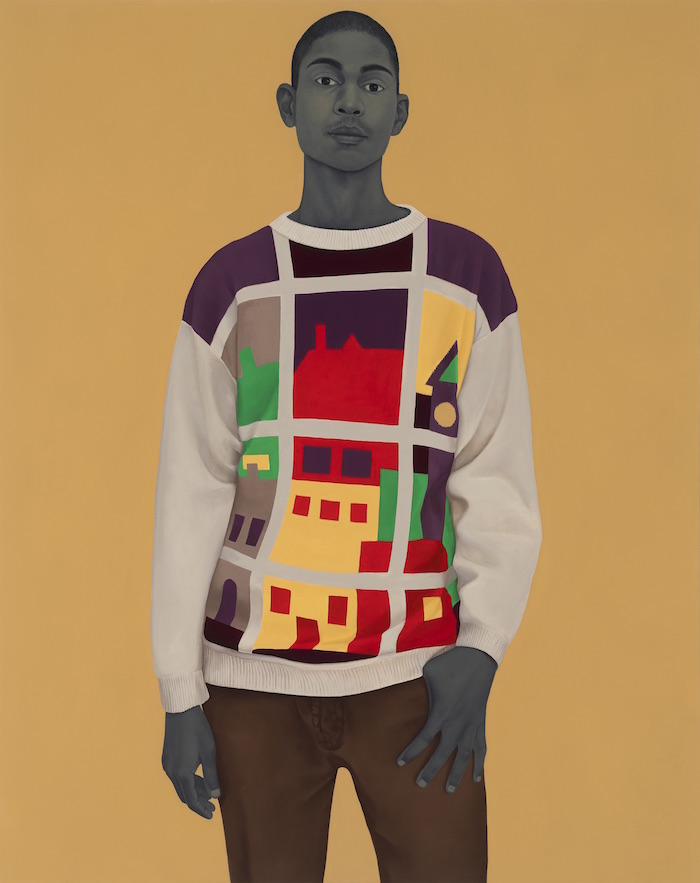

Amy Sherald and Deborah Roberts are friends, fellow southerners, and tremendously talented artists. Each in her own way makes work that is meaningful without being didactic and encourages thoughtful, critical consideration. What better people to talk with about the bounds of representation and the possibilities of portraiture? In January 2020, they caught up by phone with guest editor Teka Selman in their respective locations—Amy in New Jersey, Deborah in Austin, Texas, and Teka in Durham, North Carolina—to talk about their work, ideas, and influences. This conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Deborah Roberts: I first met you in person at Theaster Gates’s Black Artists Retreat. Then I found out we had a lot of things in common, we both did work that featured black women, and talking about beauty, and, I guess, our place in society. I think at the time you [painted] multiple ages of your girls, but they were kind of young, right?

Amy Sherald: Yeah. They were always young and not on purpose, I think.

DR: Right.

AS: When you think about it, you’re making work for everyone, but you’re really also thinking about the future and generations that are growing up to go into these museum spaces and institutions. So it came to have that meaning, but I don’t think I really thought about the ages of people. It’s just the people that I encountered happened to be teenagers or in their twenties, and it just worked out.

Teka Selman: What was it like being at the Black Artists Retreat?

DR: It was awesome.

AS: Good. For me, it was the first time I had comrades, you know what I mean? It was seeing everybody in real life and in person. I think we’re all in our studios all the time and not all of us have those communities in our cities where we get to, as working contemporary artists, come together in the same space and feel each other’s energy and talk to one another. So it was great.

DR: After that, you went on to start doing your own practice just like I did.

AS: We were around the same place in our lives, kind of.

DR: Right, right. We had been working a long time. And just sticking with it and hoping that what has happened would happen. I don’t know how you feel. I’m really happy with the success that I’ve had. I think people who want this as an artist don’t know how much hard, hard work it takes. I think this is harder than us struggling. I don’t know. That may not be your experience . . .

TS: I know so many people at the Black Artists Retreat or at any of these sort of big gatherings [who] are trying to move to New York and make it there, as opposed to staying where they are. So did you guys know that you were both not in New York? Did you know you were both from the South? Did you know you were both working outside of the two major [art markets on] the coasts?

AS: Yeah, I didn’t know Deborah was from Texas.

DS: I was still in Syracuse when I was first introduced to Amy’s work. I was still struggling with what I wanted to do as an artist, moving forward in my practice. I remember [Baltimore-based artist] Zoe Charlton saying, “Look at Amy’s work. My friend Amy Sherald. Google it.” She’s like, “Google it while I’m on the phone.” She did that to me a lot of times. She said “while I’m on the phone” because she knew I probably wouldn’t do it. I was like, “Damn, this is good.” I think the first one I saw was the girl holding the tea with the white gloves. And I was like, “Damn, why did she make me look at this?” I know part of your question is about being women from the South, how it influenced my work. When I saw that work and how beautiful black bodies are in the South, I was like, this is so very important.

I don’t use my being in Austin as any form of inspiration for my work. Austin is very, very white. It’s very white and you are almost entirely invisible. And so creating collages for me was what happened at Syracuse, but it developed more while I was in Austin because I didn’t experience—I mean, I’m from Austin, but I went away for six years and I came back and it was whiter than ever and then all of a sudden I was invisible. So creating work from that vantage point, I think, was a real boost for my work.

I don’t know how Amy feels about that because I know she was in Baltimore. Well, that’s the opposite. There’s a large black population and a lot of stuff you can mine from, a lot of stuff.

AS: Yeah. I feel like most of my inspiration did come from the South, though. I think it did. It may not have come from, I think . . . What did you say, Teka? Like going to Clark or being at a black college?

TS: Yep.

AS: But it did come from growing up in the South, specifically Columbus, Georgia, and recognizing, after grad school, the limitations of the narrative that I grew up in and somehow wanting to change that. I mean, in hindsight. I don’t think when I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do, I didn’t have all those thoughts in my head. But you do your first few paintings and you come to terms with what it is that you’re doing.

TS: When you say “the narrative,” what do you mean by that—the narrative that you grew up with? Did you feel like those were different than what you’ve heard from people who aren’t necessarily growing up in Baltimore or growing up in Georgia?

AS: Yeah, I mean, I think growing up in Columbus, it’s a very racialized experience. It’s something that you can’t really escape because the city feels segregated by one major street. I was born in ’73 so it’s a little after the Civil Rights Movement, but there was still a lot of residual racism and people still really didn’t understand color. It felt complicated. And going to all-white schools just made it feel even weirder. And then being light-skinned with kind of light brownish hair, that made it even weirder. You know what I mean? Because they were like, “We don’t know what to do with you.” They were way too comfortable around me, and I’m like, “Look.” It was interesting, but traveling outside of that micronarrative really helped me understand who I was and who I wasn’t, and that I really carried a lot of baggage from that experience around. I felt differently about myself outside of that space and city than I did when I lived there because people experienced me differently in New York or in wherever I was, in Norway or whatever. It was like I finally considered my Americanism versus my race or even my gender versus my race. Because the most salient feature about my life was my race in Georgia.

TS: It’s interesting. I think [for] me growing up in Michigan [it was] oddly similar. But I attribute that to some [of our] shared experience . . . both having dads who were black men who were dentists, and then both [of us] going to all-white schools. It creates a certain narrative around yourself. So I understand that.

And Deborah, I think it’s interesting what you said about Austin not necessarily figuring into the work because I think in a sense it actually does. You’re making work that renders visible you and people like you so that people don’t feel that they are invisible. They have a way of seeing themselves. And neither of you, in my opinion, make work that’s forcibly didactic. It’s in many ways very much about quotidian experiences. It’s layered, but it’s mundane, because that’s what life is. We’re just people, we have layered experiences. We should be able just to be, it’s not always about some performance of experience. Right? So it’s interesting to me that you have that in common.

I know, Deborah, you’ve worked different ways in your career and, Amy, I know the same is for you. How do you feel like you sort of got to a place where this felt like it was the right thing? The approach that you’re [taking] now is the right approach? Do you think you’ll change ever?

AS: No, I don’t think I’ll change because I feel like it’s personal and it’s public. Because it’s about my own personal experience, and wanting to evolve, and to focus on my interior spaces and that of other people like me, and to kind of escape that public black identity. And then we’re also free to make this kind of work because there’s artists that came before us that made that didactic work because they had to, because art was an education back then, you know? I don’t think I really realized that until I had that conversation with—I mean, I knew it, but then [photographer and artist] Lorna Simpson, I was having a conversation with her, and we were talking about that, and I’m like, “That’s so true.” Their work had to be about blackness, and we have the freedom to kind of escape that now because they provided an education for everybody, including us but also people that aren’t black, for us to be able to come in and really explore ourselves versus educating people about who we are. It’s like now we can deal with the nuances of who we are.

I think that’s really important too, within this art historical narrative, to be a kaleidoscope and present ourselves that way because that’s who we are. We’re not a monolith. That’s really important to portray in visual culture and that’s what I’m focusing on.

DR: I do feel like my work is changing and I don’t know why. I think it has changed probably as I have changed. It changed when I turned forty, and I’m having a lot of success and it’s starting to change again. It wants to change. I don’t know what that really is about, but I’ve always allowed it that change. I never stopped it and said, “Okay, this is it. We made it so let’s just stop.” And it’s fracturing, the work is fracturing. I can see it when I lay out my collages, I can see it when I think about what I want to talk about and I can either allow it to happen or I can control it. I think that’s where I’m at right now, trying to figure out which is the right thing to do with that.

I think Amy’s right, and there’s so many different ways of talking about it. I don’t know if it’s [the] desperate times influencing my work. I feel like we have to, sometimes as black people, be chopped up so much just for people to accept and to digest us, instead of taking us as a whole individual. I feel that. I think we were safe with Obama. I really felt we [were] just lulled into this safety. With these last three years with Trump—I mean, the hate has always been there. But right now it’s so, so desperate out there. People are angry. I mean, you can just kind of bump somebody and they will just go totally off on you. So I don’t know if that’s what’s causing my work to fracture more or just vulnerability to black bodies. Why [are] so many black girls committing suicide? I don’t know. It’s something that’s happening that’s causing my work to shift and I have to allow it to.

TS: Well, yeah, that just speaks to the fact that just like there’s no one way to be a person, there is no one way to be an artist, you know?

AS: Yeah, I just don’t see it drastically changing. I guess I need to change my vocabulary because I look at it, I’m like, “Yeah it’s getting better. Like, I’m getting better.”

DR: Awesome.

AS: It’s not changing, it’s getting better.

DR: I didn’t want to say it. Mine is getting better, too. Yeah, it’s getting better.

TS: That’s actually true. Both of your work is getting better. That’s the idea—the idea is you’re an artist, you have a career. It’s long and the work develops and you develop and you get better at it like anything.

DR: Yes, ma’am.

TS: It’s great.

AS: Deborah and I have conversations about how to continue to challenge ourselves and how to stay on top. The strategy of making work and consistently making work, and what that means for an artist’s practice. Because you constantly have to be thinking and challenging yourself and you can’t get comfortable.

DR: I know. I tell Amy, “Take a break, take a break, take a break.” You have to, because you can just get . . . I do too. I don’t do it all. You just get all in it and it’s a lot of pressure, a little bit more pressure than I thought. If you don’t take a break and just take some time, even if it’s three days. I remember in 2017 I was just going all the time. I developed a headache from just going all the time, all the time, all the time, creating so much work. I mean, I was feeding the beast. So I’m definitely taking more time off.

TS: I personally think that there’s a way in which as artists of color, or as curators of color, art dealers of color, whatever, there is a pressure. The sense that you have to grab everything and every opportunity because it might not be there. There’s a certain kind of pressure and I wonder for you both with the success that you’ve had, I think that, Deborah, you’re speaking to this basically like this pressure that happens. I mean, I’m sure it happens for all artists, but I think it happens for us in a different kind of way.

DR: Right.

TS: You don’t know if it’s a trend, you don’t know if it’s going to stick.

DR: Exactly.

TS: To bring it back a little bit to the question of the South, do you feel that there actually is such a thing as southern art, so to speak, or a southern aesthetic in any sense?

AS: Like the difference between Lil Wayne and Jay-Z? Like trap music versus rap music? I don’t think so. I feel like all of our experiences are different growing up in our respective cities, like growing up in New York versus growing up in Georgia. But I still feel as if the ideas and the narratives and the kind of identity codifications that happen exist in the same way. It’s just that there’s a level of multiculturalism that exists in the North—well, at least in larger cities that I didn’t grow up in. Atlanta was a very black city. So, I don’t know. I mean, I guess off the top of my head, I say no, I don’t think so.

DR: The only reason I think [there] is a southern type of art [is] because, you’re right, when I went to Atlanta for [my exhibition at Spelman College Museum of Fine Art], I went to studio visits with other Atlanta artists. I felt it was the black romantic versus the contemporary modern.

AS: Really?

DR: Yeah. I felt like that work was more southern because it was more based in religion. I can’t explain it. I don’t know how to explain it.

AS: Maybe more figurative?

DR: Yeah, it was more figurative. . . . It just didn’t feel like that hard, contemporary work that people see coming out of the studios in New York City. I felt that a little bit.

One of the things that I purposely don’t do in my collages: nobody’s crying. First of all, nobody’s crying. It’s just, there’s no time for tears. It’s just, that’s over. And the pleading, if I have any hands grasp in my work, it’s more about saving a life than asking for the life to be saved. So that’s different.

AS: It’s more illustrative. I guess you could say that. It’s more illustrative.

DR: Yeah, exactly. The colors are more warm and more embracing. . . . Yeah, I think there’s a difference.

TS: That’s almost like a geographical dialectic, right? When I think about black romantic, I tend to think about that being work specifically made by black people for black people, about love and community that wasn’t appreciated in the wider world. I don’t know, it’s sort of an impossible question to answer, but I had to ask it anyway.

So what are you most excited about that’s coming up?

AS: What am I excited about? I’m excited about going to LA to see my friend Calida Garcia Rawles’s opening at Various Small Fires. She did the cover of Ta-Nehisi [Coates]’s last book. We went to Spelman together. She’s living her best life now and I’m really excited for her.

DR: That’s lovely.

TS: That’s amazing. It’s also amazing when you see people like—I feel like there’s a community of people who’ve all sort of come up and are having a moment at the same time. So inevitably there’ll be people that you know or went to school with or interacted with in some way and suddenly you’re like, “Oh, that person’s doing this amazing thing.” You know? Deborah, what about you?

DR: Well, I’m going to Africa for the first time in the middle of the year, either May to June or June to July, and I’m going to go for ten days. I’m going to go to Senegal, and I’m interested in sharing what it’s like to see the colors.

I think that black strength comes from somewhere. I mean, to be able to be descendants of people who had to go across the Atlantic on a boat, a raggedy old boat, tossed on top of each other, and to survive it. We are a part of that. That we don’t celebrate enough. I want to go and experience that because I think that when people know where they’re from, it’s a big deal. It’s a part of your identity. And so for me to spend some time investigating that not as an artist, just as a human being, because I haven’t done anything as a human being in a long time.

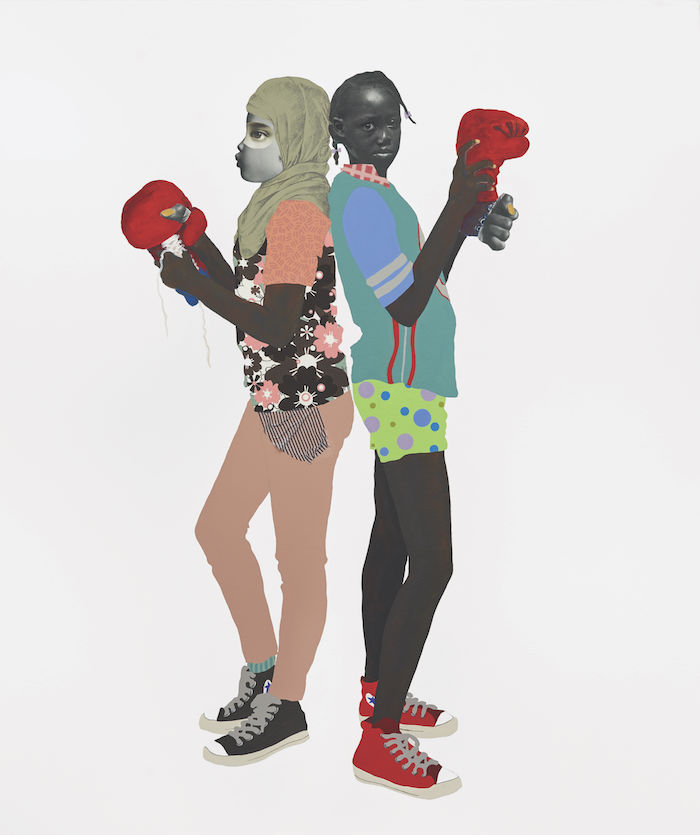

Deborah Roberts is a mixed media artist whose work challenges the notion of ideal beauty. Her work is in the collections of venues including the Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Roberts is the recipient of the Anonymous Was a Woman Grant (2018), the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant (2016), and a Ginsberg-Klaus Award Fellowship (2014). She received her MFA from Syracuse University, New York. She lives and works in Austin, Texas.

Amy Sherald was born in Columbus, Georgia, and lives in New Jersey. Her large-scale works document contemporary African American experience in the United States through arresting, otherworldly portraits. Sherald received her MFA in Painting from Maryland Institute College of Art (2004). In 2016, Sherald was the first woman to win the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition grand prize. Sherald has had solo shows at venues including Hauser and Wirth (2019), Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (2018), and Monique Meloche Gallery (2016).

Teka Selman is an independent cultural advisor who has been in the contemporary art world for over twenty years, collaborating with artists, collectors, and institutions as a curator, writer, and consultant. After honing her skills in Chicago, London, and New York, she relocated to North Carolina, drawn by the burgeoning art scene of the Southeast. She is cocurator—with Lauren Haynes—of the inaugural Tennessee Triennial, slated to open in venues across Nashville, Knoxville, and Memphis in 2021. Teka lives in Durham, North Carolina, with her husband and two daughters.

Header image: Deborah Roberts, When you see me, 2019. Mixed media and collage on canvas, 65 × 120 in. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. © Deborah Roberts.